Sometimes-wicked appropriations from such disparate sources as neoclassical history painting and the Dutch golden age root Hempel's art in a revised history.

October 08 2011 4:00 AM EST

February 27 2017 11:39 PM EST

xtyfr

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Sometimes-wicked appropriations from such disparate sources as neoclassical history painting and the Dutch golden age root Hempel's art in a revised history.

For decades, Wes Hempel has been committed to reenvisioning the depiction of masculinity in contemporary art. By setting psychologically acute portraits of modern-day men against backdrops appropriated from such disparate sources as neoclassical history painting and Dutch golden age landscapes, the artist's works forge provocative dialogues between the exigencies of the present and its endowments from the past.

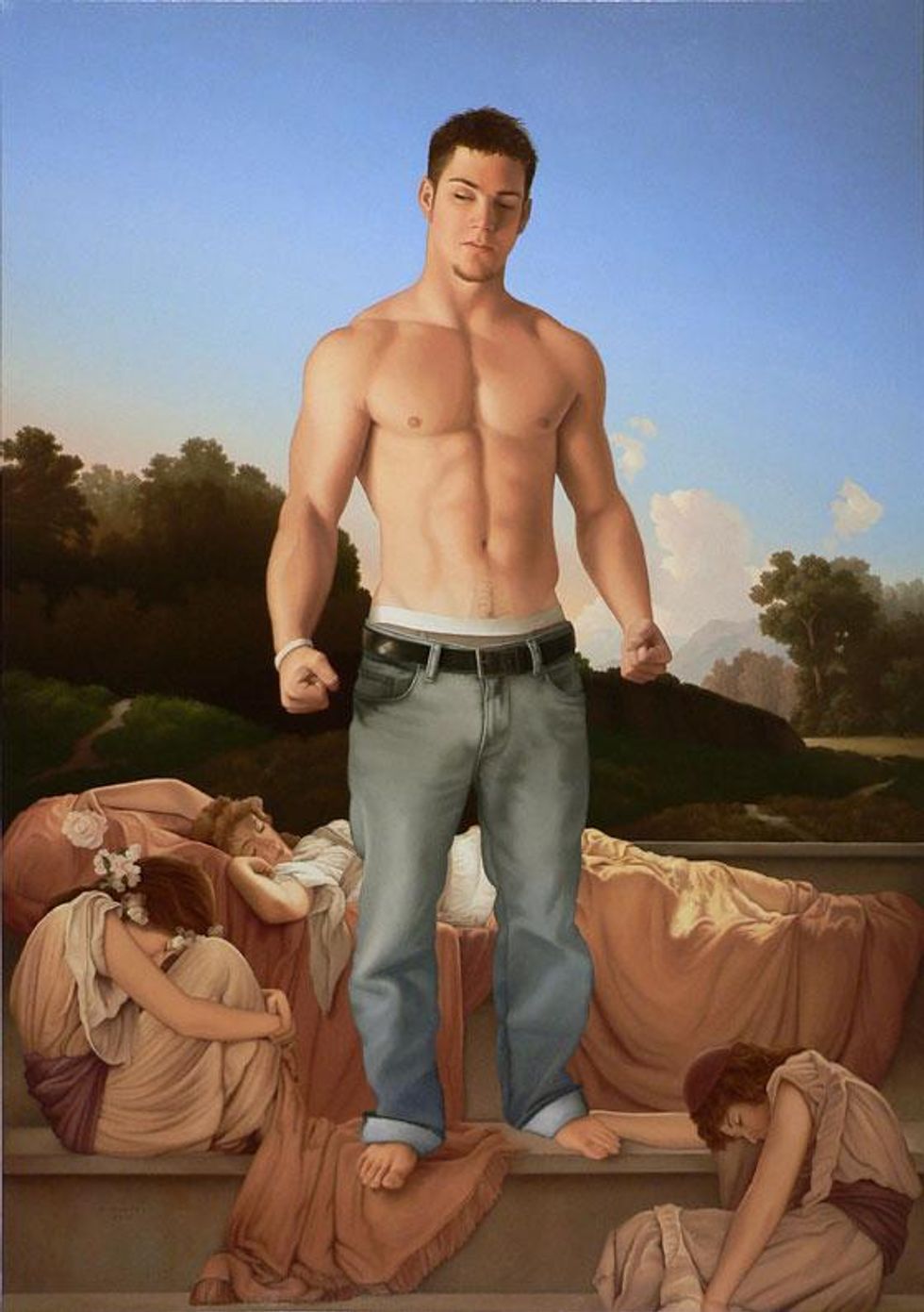

Joining the mythic allusions and technical fluency of classical art with the ideas of personal narrative and social content of postmodern art, Hempel's paintings explore the divide between the ancient and modern, reason and passion, august ideals and the profoundly individual. The artist recasts modern male figures in historical and culturally iconographic settings, provoking both a rethinking of assumed narratives and mythic themes and inviting a similar reconsideration of contemporary life, masculinity, and sexual norms. Hempel's societal investigations are rendered in sensuously modeled flesh tones, gleaming marble surfaces, and the immersive depth of Arcadian landscapes -- proving as visually seductive as they are conceptually rigorous.

Hempel's art has been the subject of more than 80 solo and group exhibitions and is included in a growing number of esteemed private and corporate collections, including those of the Denver Art Museum, the Columbus Museum, the Arnot Art Museum, Microsoft Corp., the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, and the New Britain Museum of American Art.

The Advocate: Why are you an artist?

Wes Hempel: I always wanted to be a writer, but in graduate school, I began playing around with some old brushes and paints that my partner, Jack Balas, had given me. I was mesmerized. I completed my degree in creative writing and began teaching at the University of Colorado in Boulder, but I had fallen in love with art. Jack showed some of my early pieces to his gallery in Denver, Robischon. They gave me a show, which sold out. I've been painting ever since.

What catches your eye?

There is something specific I'm always looking for, though it's hard to put into words -- the visual equivalent of a deftly turned phrase or the unexpected image in poetry. In painting an emotional quality can arise from the interplay of composition, color, and value, regardless of subject matter.

Tell us about your process or techniques.

It's a very traditional technique. These days I do a full-color underpainting in oils -- sometimes with the help of an assistant -- on gessoed canvas, then apply one or more top coats, making adjustments to form and to heighten the richness of hue and quality of light. I also use glazes to add surface depth and to complicate the coloration. I have a few tricks I've developed along the way -- I suppose most painters have these -- that I hold close to my chest.

How do you choose your subjects?

One of my ongoing projects is a reenvisioning of what art history might have looked like had homosexuality not been vilified in the culture. The paintings one sees in museums are revered in part because they enshrine our collective experience. But it's a selective past that gets validated. By presenting contemporary males as objects of desire in borrowed art historical settings, I'm able to imagine -- and allow viewers to imagine -- a history that includes rather than excludes gay experience -- and thereby ride the coattails, as it were, of art history's imprimatur.

What artists do you take inspiration from and why?

This changes all the time for me. When Jack and I first moved to Boulder, I took a year off from working and went systematically through the art library at CU, taking down each book and carefully going through it. It took me the entire year to work my way through the shelves. I used to joke that my faulty knowledge of art history is the result of the books that were checked out.

Hempel: A take on a painting by the same name by Venezuelan painter Pedro Centeno Vallenilla (born: Barcelona 1904, died: Caracas 1988). As part of my ongoing project of reenvisioning art history from a gay perspective, I've replaced the nude female in the original (lying on the branch to the left) with a nude male.

I usually work out my ideas fairly comprehensively before committing paint to canvas, but occasionally I run into problems. Living with another artist means I have someone to consult with, and Jack is often more inventive visually than I am and more adventurous when it comes to imagery. He can think spontaneously in spatial terms, which means he has a fuller visual vocabulary than I do. Sometimes his ideas are so good, it makes more sense for him to just take over the painting. The canvas then goes from my studio to his (we never work on a piece together in the same space), and I relinquish control to him, which I admit is scary. Almost always, though, I'm delighted with the end result.

The model, Joe M., was a student at the University of Arizona in Tucson, where Jack and I spend winters. He'd recently been in an accident, the nature of which I should leave to him to disclose. I thought this image conveyed something of his climbing out of that circumstance and of his natural beauty, which, as the viewer can see, remains intact.

I was initially drawn to the Vermeer interior because of the extraordinary quality of light. But I'm also playing around with the contemporary painter George Deem's campy idea of How to Paint a Vermeer (title of a book of his paintings). So the piece may be humorous on various levels. And yet I think there's a poignancy lurking underneath that has to do with the portrait on the wall (the same person as a boy?) and the way the young man presents himself now.

The female figures are taken from Maxfield Parrish's 1912 illustration for the Sleeping Beauty fairy tale. In the original story, the prince kisses Sleeping Beauty and awakens her from her trance. But this particular "prince" (our model Sye), having arrived late on the scene, seems to have trouble making up his mind what to do next. A decision seems to be in order, but it's left to the viewer to imagine what is going through the young man's mind as he squints into the distance, clenching his hands.