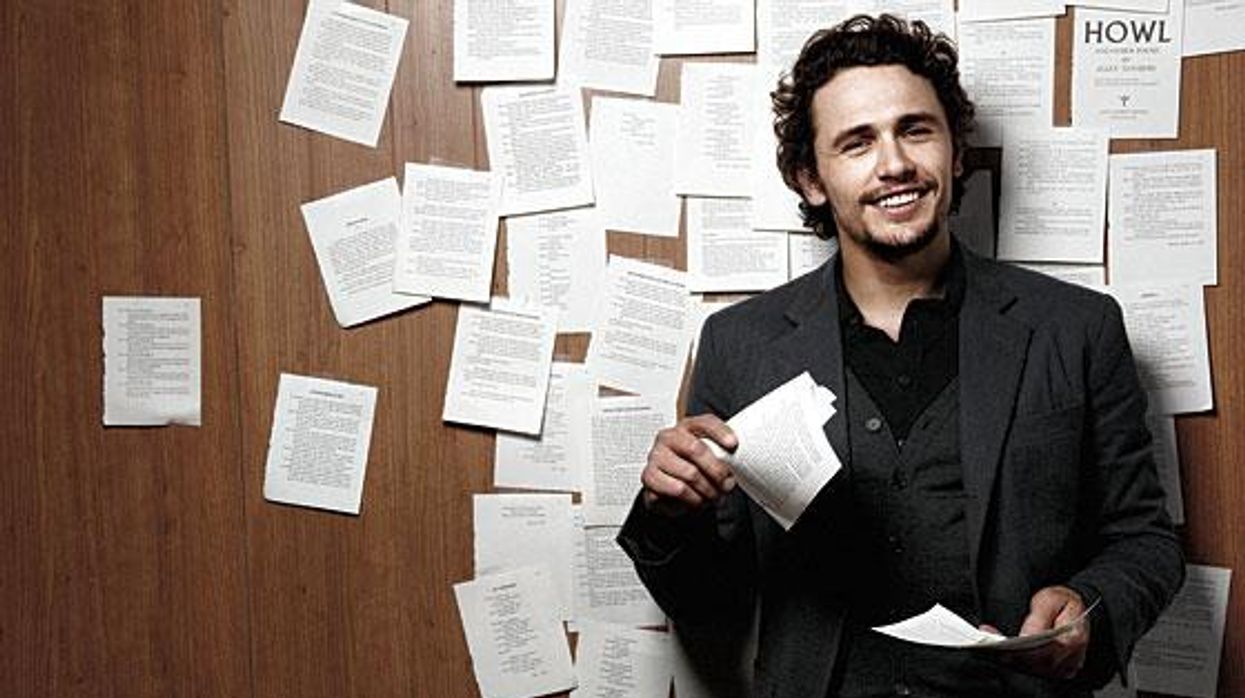

James Franco is whispering to me about gay poetry. We're seated by a window in the upstairs poetry room at City Lights Books in San Francisco, where several earnest-looking college students pretend to read obscure poetry collections. Franco speaks softly so that he doesn't disturb them.

They're not disturbed, of course. If anything, they'd probably like the 32-year-old, who's hiding his curls under a San Francisco Giants hat, to speak up--to project. But to Franco, a poetry room, especially one with such a strong connection to Allen Ginsberg, a man Franco has admired for years and portrays in the upcoming film Howl, is a serious place where people ought to be allowed to read in peace.

I lean in closer. "When I read a poem that inspires me, I don't question it," he says, turning in his seat to gaze toward the brick apartment building across the alleyway, where a woman's chubby hands extend from an open window to adjust a drying T-shirt on a stained laundry line. It's an unusually hot day in San Francisco, and only blocks away the city is celebrating gay pride by dancing on floats and trying to keep up with the overwhelming number of possibilities on Grindr.

Here, though, in this room that celebrates the Beat Generation--where a sign reads "Printers' ink is the great explosive"--Franco is explaining his interest in "The Feast of Stephen," a gay-themed poem he adapted into a short film of the same name for his course work at New York University. (In addition to completing his thesis at New York University, Franco received an MFA from Brooklyn College, and this fall he'll begin work toward a Ph.D. in creative writing at Yale University. More on Franco's love of homework later.)

The Feast of Stephen, the film, looks like something a young Gus Van Sant might have dreamed up: sweaty, sinewy teenage jocks play basketball shirtless on an outdoor court while a gay boy watches and fantasizes about them gang-raping him and smearing feces on his face. It's a creepy film, and I can't help but wonder if Franco, who considers Van Sant one of the greatest directors to ever live, subconsciously made the movie to impress him.

Although Franco tells me he doesn't question inspiration when it strikes, it's not an answer I'm prepared to accept without a fight. Franco is heterosexual (unless everyone who knows him well--including his girlfriend of five years--is lying or has been monumentally duped), yet he is routinely "inspired" to direct or play gay.

In addition to the two gay-themed poems he adapted for student films (Frank Bidart's "Herbert White" being the other), Franco portrayed a 17-year-old swimmer dating an older man in the gay indie film Blind Spot and Harvey Milk's lover in Milk. He also French-kissed Will Forte on Saturday Night Live, took a queer studies course at NYU, and created performance art pieces about gender and sexual confusion. And then there's Franco's first solo art show this past summer in New York City; it featured video monologues with lines like "We're all gender-fucked--we're all something in between, floating like angels."

And now, just in case Franco hasn't confounded us enough (and blown the lid off the conventional thinking about how many gay projects an A-list actor can tackle without imploding), he's taking on arguably his most challenging role yet: iconic gay poet Allen Ginsberg, a man who discovered within himself "mountains of homosexuality."

As the City Lights poetry room grows suspiciously crowded with gay men (has someone alerted a float?), I ask Franco what attracts him to gay roles. He leans back in his chair and ponders the question. "In this history of cinema, there are so many heterosexual love stories," he whispers. "It's so hammered, so done. It's just not that interesting to me. It's more interesting to me to play roles and relationships that haven't been portrayed as often."

"If you were gay or bisexual, would you tell me?" I ask him. "Are we at a point where someone like yourself could matter-of-factly come out without the world stopping for a day or two?"

He smiles and glances out the window. One of the college students shuffles closer. "Sure, I'd tell you if I was," he says. "I guess the reason I wouldn't is because I'd be worried that it would hurt my career. I suppose that's the reason one wouldn't do that, right? But no, that wouldn't be something that would deter me. I'm going to do projects that I want to do. Everyone thinks I'm a stoner, and some people think I'm gay because I've played these gay roles. That's what people think, but it's not true. I don't smoke pot. I'm not gay. But on another level, there's something in me that is able to play roles like that in a way that's convincing."

I'm curious what that something is. Can he relate to sexual confusion? Does he secretly want to be gay? His girlfriend, actress Ahna O'Reilly, laughs when I phone her later and suggest the second possibility. "If he does, it's news to me!" she says, adding that Franco's interest in sexuality is less about homosexuality and more about boyhood, masculinity, and journeys of self-discovery. Franco's favorite movie is My Own Private Idaho, Van Sant's 1991 surreal update of Shakespeare's King Henry plays, which stars River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves and is certainly about all of those things.

"I've loved that movie since before I was an actor, when I was in high school," he says. "I suppose the aesthetics struck me. I loved the makeshift family, the idea that people could come together and survive. I loved the clothes. And I am sure the performances were what I was mostly drawn to, especially River's. He's vulnerable, quirky, cool, and clownish. He's like James Dean and Charlie Chaplin. I am sure I was drawn to his character's quirkiness and desire to be loved." (Franco and Van Sant are currently working on an art project reexamination of Idaho using never-before-seen footage.)

Though Franco didn't know any openly gay people in his San Francisco Bay area high school ("It was not considered a good thing to be gay," he says), he doesn't remember ever having negative feelings about homosexuality. "My friends and I read the Beats, so we were familiar with gay characters," he says. He also grew up in a liberal household--his mother is a poet and author--where he says it was OK to be unique and artistic.

I ask Franco if he's ever been counseled to slow down on the number of gay-themed projects he accepts. He shakes his head. "You want to know what my agents did try to talk me out of?" he says. "General Hospital. They didn't think me acting in a soap opera was the greatest idea. But they know that I've always wanted to do a movie about the Beats, so no one tried to stop me from playing Allen Ginsberg." At first blush James Franco as Allen Ginsberg seems like a counterintuitive casting choice. Dustin Lance Black, who wrote the screenplay for Milk and got to know Franco on set, recalls his surprise when Howl codirector Rob Epstein told him that he and collaborator Jeffrey Friedman had selected Franco for the role. "My surprise wasn't based on the fact that James would play another gay role, because nothing James does surprises me anymore," Black says. "I just had a hard time wrapping my head around how James, who is one of the most handsome men in the world, was going to play Ginsberg, who had, shall we say, average looks. Would the audience be able to get past it?"

It was one thing for Franco to portray James Dean, as he did for a TV movie in 2001. That was a case of a hot young man playing the part of a hot young man, and it made sense--and won him a Golden Globe. But Ginsberg? Balding, curmudgeonly Ginsberg? Why not cast Franco as Barney Frank while you're at it?

Van Sant, an executive producer of Howl, says Ginsberg, would have approved of the casting choice. "Allen was a bit vain, and I think he would have been delighted to be portrayed by James Franco.... It's important to remember that Allen is a young man in this film, and he wasn't a bad-looking young man. It's not as big a stretch as you might think." Indeed, in Howl, Franco doesn't look all that different from a young Ginsberg.

Casting Franco certainly wasn't a stretch for Epstein and Friedman once they heard Franco read the first few lines of the landmark 1956 poem: I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, / dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, / angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.

"He blew us away," Epstein says. "It was hard for us to imagine anyone being able to embody a young Allen, but James just threw himself into the role and knew what was going on emotionally and intellectually for Ginsberg in every line of the script. He so gets into Allen's skin. It never feels like impersonation. It feels like a deep, nuanced understanding."

That first impression doesn't surprise Vince Jolivette, Franco's close friend and producing partner. "James is probably more similar to Ginsberg than any other character he's had to play," Jolivette says. "They're both writers. They're both poets. And they're both fascinated by art and who gets to decide what art is."

That's certainly a big theme in Howl, which centers around the obscenity trial of City Lights owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who published the poem in the fall of 1956. In March 1957, less than two years after Ginsberg, at 29, first read "Howl" publicly in San Francisco, U.S. Customs agents seized copies of the poem as the books were on their way from England, where the second edition had just been printed. Police arrested Ferlinghetti and charged him with publishing obscene material, leading to a historic free speech trial at which literary "experts" debated the merits of a poem with lines that include "holy the cocks of the grandfathers of Kansas!" and "who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy."

The film explores a Ginsberg many people don't know, one who Friedman says "was searching for a way to express fully who he was" in his writing, friendships, and love life. "Ginsberg at that time was still trying to figure himself out and figure his work out," Franco adds. "He wasn't the wise old man that many people remember him as."

In Howl we learn that a young Ginsberg struggled with deep shame about his homosexuality, and we watch as he tries, for a time, to be straight. We get glimpses of his three early love affairs--with Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady, and Peter Orlovsky, who was Ginsberg's partner for 43 years (until Ginsberg's death in 1997). But mostly we're treated to a celebration of the pursuit of creativity and authenticity in life and in art. Franco is at his best in a re-creation of an unpublished interview that Time magazine is rumored to have conducted with Ginsberg, where the young poet articulates his belief that there should be no filter between a writer's personal experiences--including his sexual appetite--and what he includes on the page. Ginsberg believed that to combat a repressive society, poets needed to serve as models for rigorous honesty and self-examination. He believed in "total confession" and in showing "his asshole to the world." As Ginsberg would later say, "You don't have to be right. All you have to do is be candid." James Franco was a brooding, troublemaking 15-year-old when a friend first introduced him to "Howl." Franco--a voracious reader who loved Faulkner, Hemingway, Kerouac, and Melville--and his friends were so inspired by the Beats that they made the occasional drive north from Palo Alto to City Lights. "I don't think I understood most of 'Howl' when I first read it," Franco says. "I didn't catch all the autobiographical and biographical references, and I certainly didn't know what he was doing with tempo and lineation and syntax."

But like many young people before and since, Franco was drawn to the poem's lyrical language and its ballsy, counterculture bravado. At about the same time he first read "Howl," Franco was partaking in his own rebellion of sorts. He was arrested for graffiti and underage drinking and was involved in a "cologne-stealing ring," in which he and some friends swiped bottles from department stores and then sold them to fellow students. (More than a decade later Franco became a model for Gucci's men's fragrance line.)

Franco pulled himself together for his last two years of high school (throwing himself into acting and painting) and was admitted to the University of California, Los Angeles, where he stayed for a year before dropping out to pursue acting full-time.

He got his break less than two years later, when Judd Apatow cast him in the television series Freaks and Geeks. Franco's first major film role was in the romantic comedy Whatever It Takes, where he starred alongside his then-girlfriend, Marla Sokoloff. He followed that with the TNT biopic James Dean and a year later with the role of Harry Osborn in Spider-Man.

Franco concedes that he was often difficult on movie sets, irritating cast members with his intensity--and occasionally trying to tell directors how to do their job. "I used to approach acting with a very antagonistic [attitude]," he says. "I was very hard to get along with, and it made working in film very unpleasant. It also hurt my performances. Now I think about acting differently. I feel a little detached from acting, actually. I still work really hard, but for my own sanity--and everyone else's--I've had to surrender the results."

Coinciding with the change in attitude was a return to academia. Franco finished at UCLA and then enrolled in four graduate programs--two for fiction, one for poetry, and one for film. "I think all of his friends asked him, 'Why are you doing this, you crazy person?' " girlfriend O'Reilly says. "One graduate program is hard enough, and he's going to do four? But ever since he's gone back to school, I've seen a transformation in him. He's just happier. He can't get enough of it."

How does he get it all (films, graduate work, art) done? For one thing, he rarely sleeps. But he's also quite possibly the most focused human being currently walking the planet. Franco's youngest brother, 25-year-old actor David Franco, recalls what it was like to live with James for a year in Los Angeles. "I would come home and he would be writing on the computer, reading a book, listening to music, and watching television all at the same time," David says. "I was, like, 'Dude, chill out.' I did this interview with him recently where I asked him when was the last time he did absolutely nothing. He couldn't understand what I was talking about. He said, 'What do you mean?' So I tried to explain it. I said, 'You know, you go to the park with your friends or you just relax and watch TV.' He said, 'I don't know what that means.' He literally does not understand the concept of downtime, of doing nothing." O'Reilly shares a telling anecdote: When Franco was 4, someone close to the family died. Franco's mother explained to him what dying meant, which prompted little James to burst into tears. "But I don't want to die!" he wailed. "I have so much to do!"

These days, Franco spends most of his time writing. He's had fiction published in Esquire and McSweeney's, and in October, Scribner will publish Palo Alto, a collection of his short stories. "I think James is as passionate, if not more passionate, about writing than acting," O'Reilly says.

But he seems less able to "surrender the results" when it comes to his writing. The response to Franco's fiction has occasionally been brutal, and O'Reilly says she's had to help him understand that while some of the criticism may be fair, much of it isn't. "Because of his fame, it's really hard for people to be completely objective about his writing, whether they're an actual reviewer or a fellow student in a writing class with him," she says. "Because he tries to do so much and is so out there with his work, some people are going to try to tear him down. So it's hard for him to get a true gauge of what people think and of the quality of the work. Whenever things get touchy, I remind him that the only thing he can do is try to write what he thinks is good."

At a bar near City Lights, I ask Franco what it would mean if--unlike Allen Ginsberg--he isn't remembered for his writing. Could he be content being remembered only as a very good and very famous actor? "I don't want to sound defensive at all," he says, sounding defensive, "but if websites like Gawker.com or PerezHilton.com don't like my writing, I can live with that. There is this crazy phenomenon in the blogosphere that is so hostile to anyone being creative, and if I incur that hostility from people who've probably read five short stories in the last 10 years, it doesn't really bother me. I applied to 15 creative writing Ph.D. programs. I got into 14. Some of them only accepted one fiction writer. I know there's this idea that I'm getting a lot of opportunities because I'm a celebrity, and there certainly is truth to that, but it's not like I'm coasting. I'm working all the time. Short of writing under an alias, I'm doing everything I can to treat this as seriously as I can."

As serious as Franco takes his writing--and his life--O'Reilly says he's also "the goofiest" person she knows. "Prior to these last couple of years, I think people only saw James as this brooding James Dean kind of guy," she says. "Then people saw him in Pineapple Express"--where Franco plays a lovable, Guatemalan pants-wearing weed dealer--"and realized what all of his friends have always known. James is both the most serious and the goofiest guy around. In some ways he's not that far off from the role he played in Pineapple Express."

Minus the weed, of course. Unlike Ginsberg, who took LSD for the first time in 1959 in Franco's hometown of Palo Alto, Franco doesn't drink or do drugs. When I e-mail him weeks after our meeting to ask why, his reply is short and sweet. "No time, really."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.