CONTACTAbout UsCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Equal Entertainment LLC.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

Scroll To Top

![]()

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

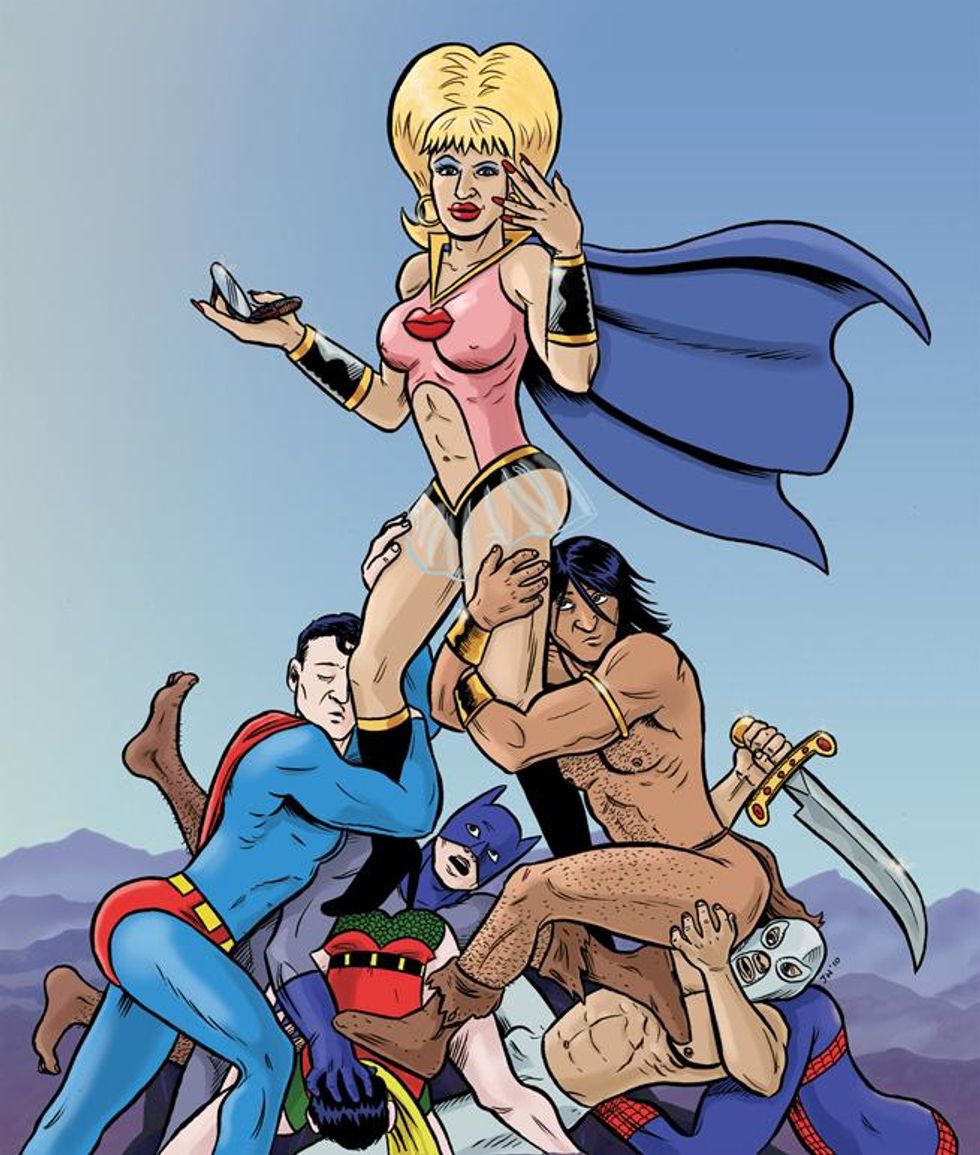

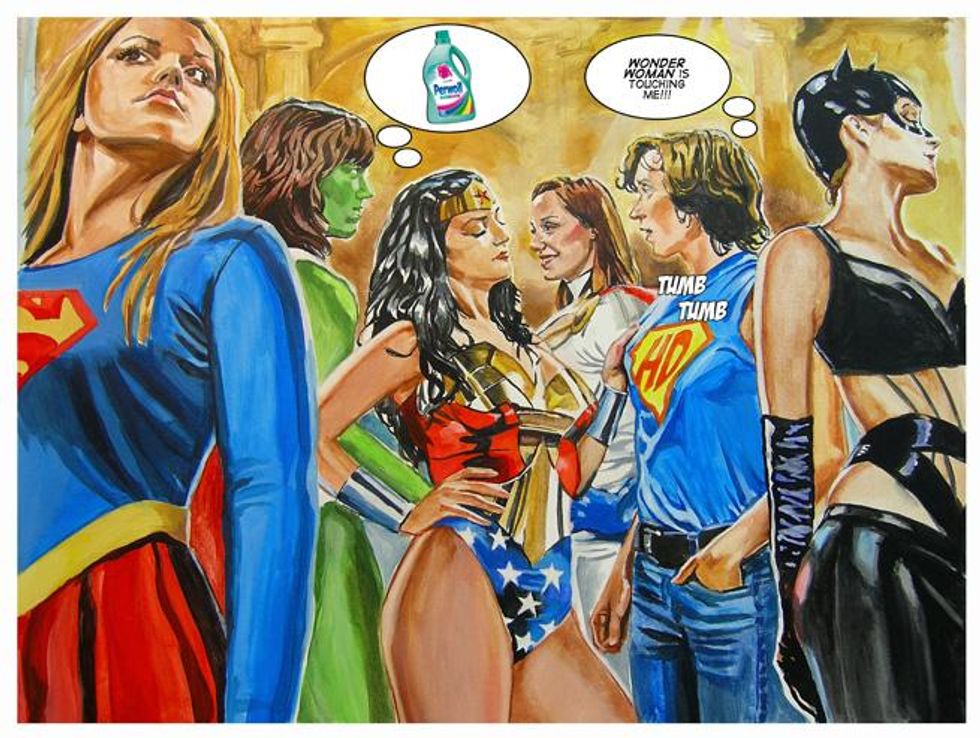

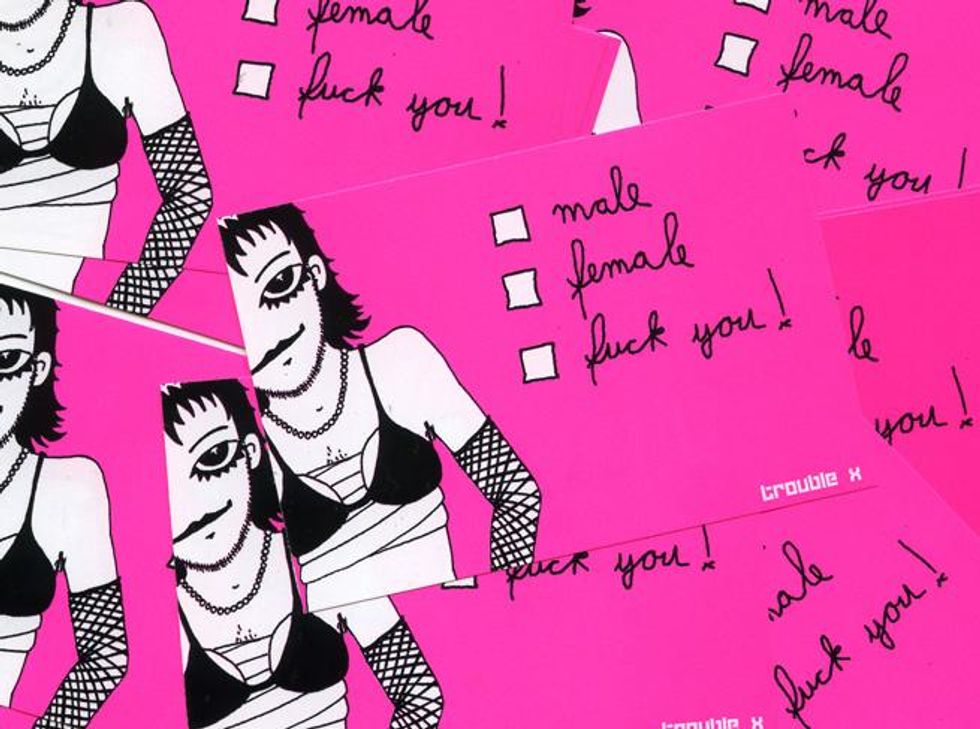

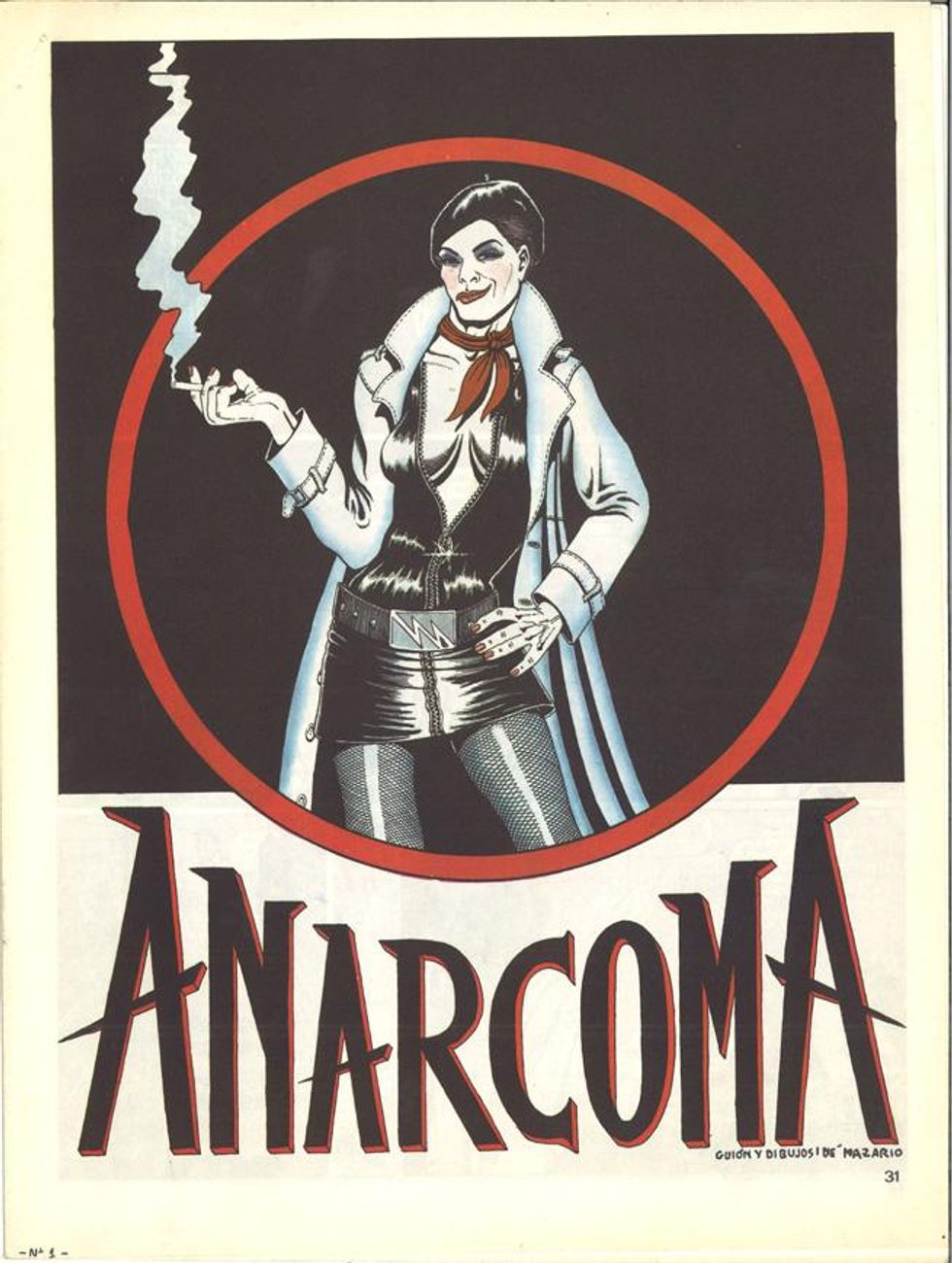

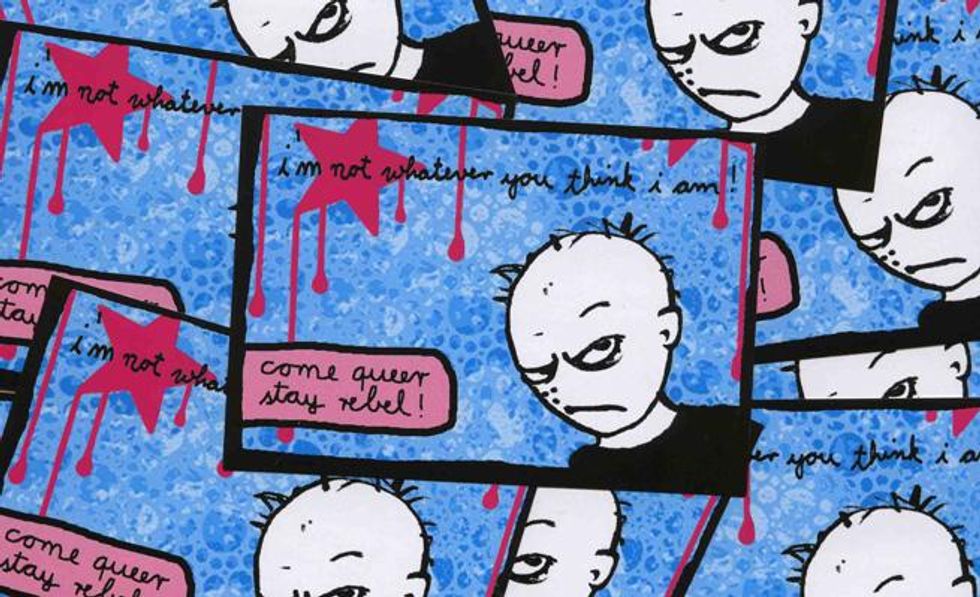

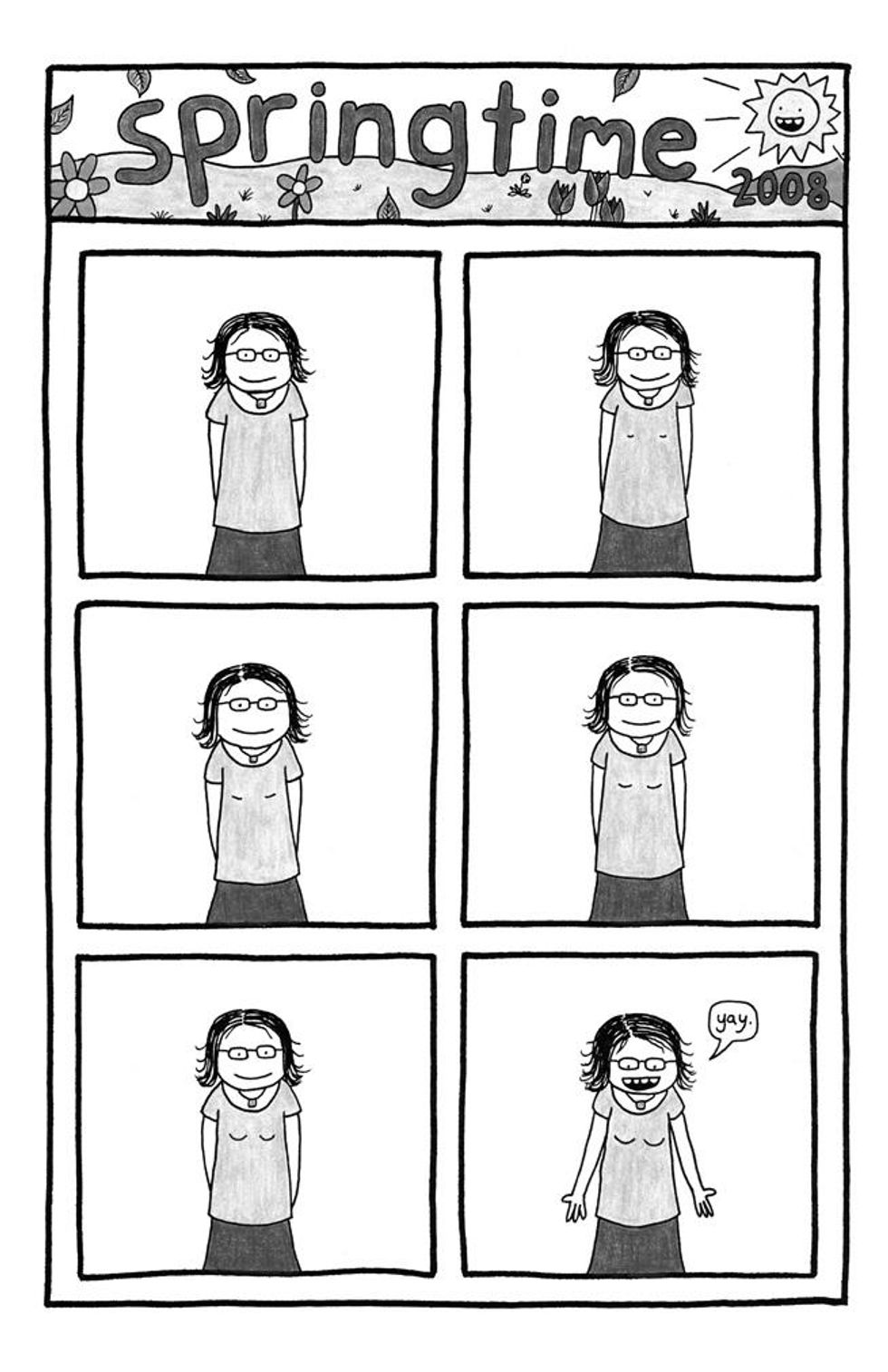

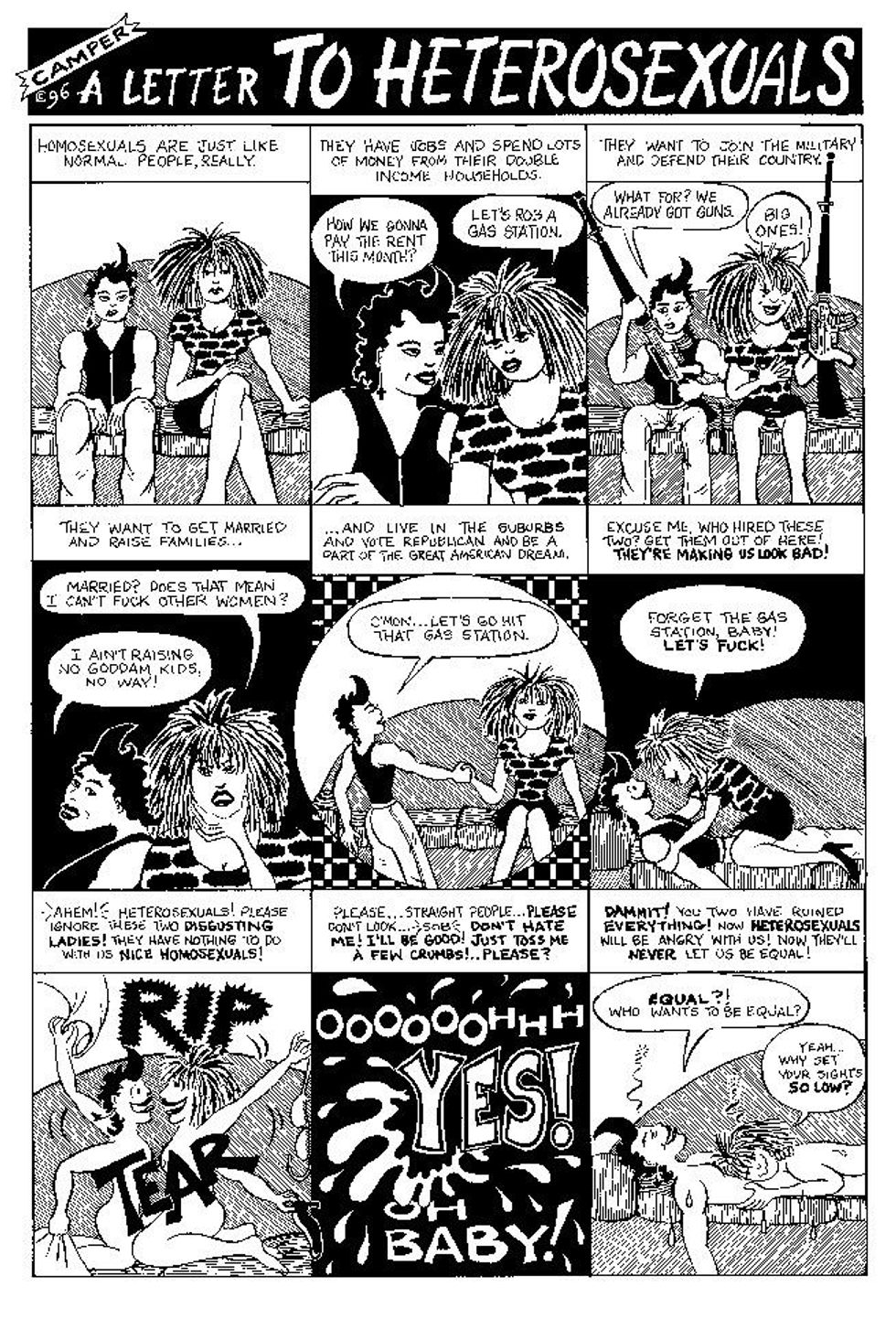

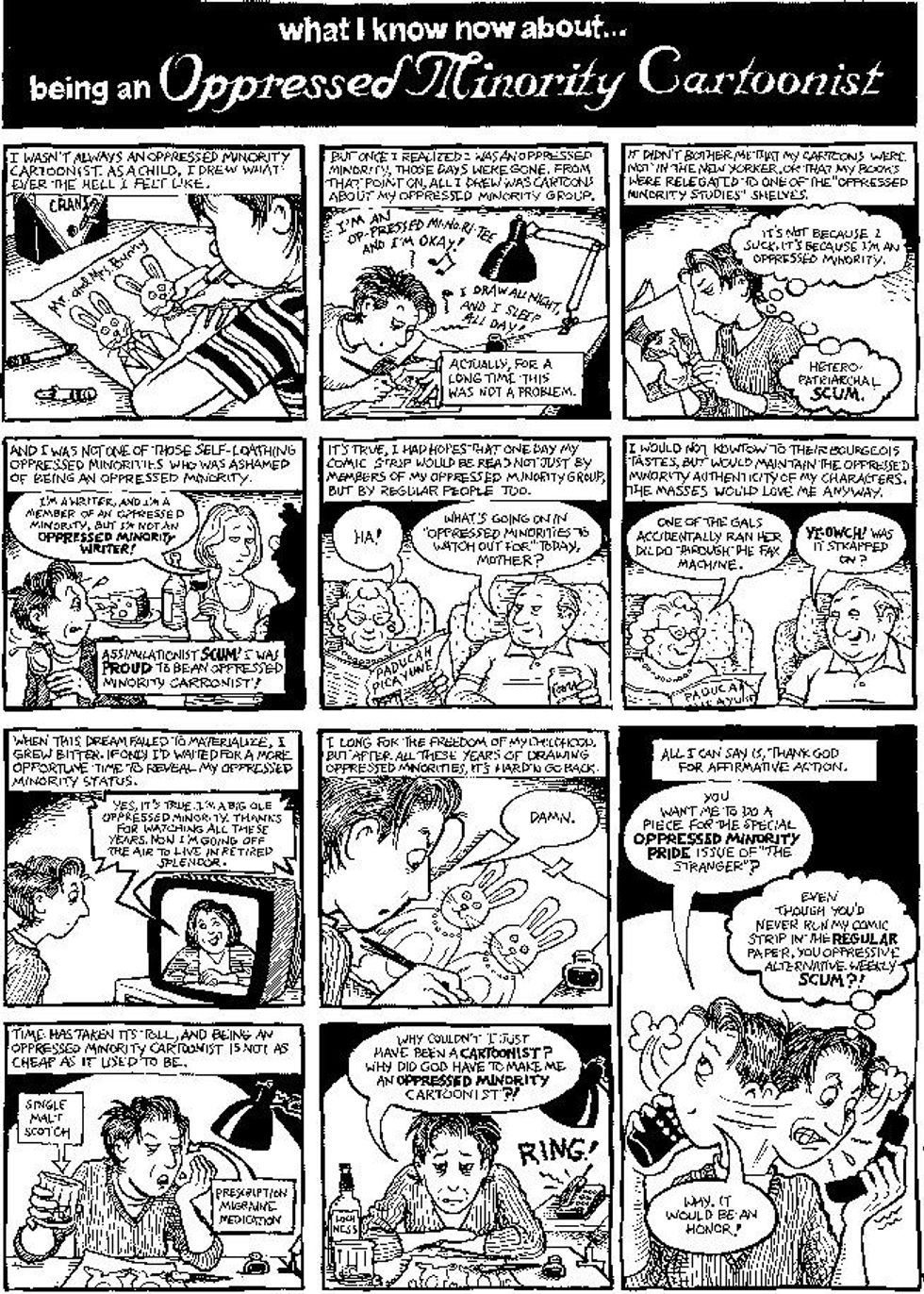

Superqueeroes

The topic of queer comics and superheroes is getting a power boost with the first European museum exhibition dedicated to the genre, "Superqueeroes."

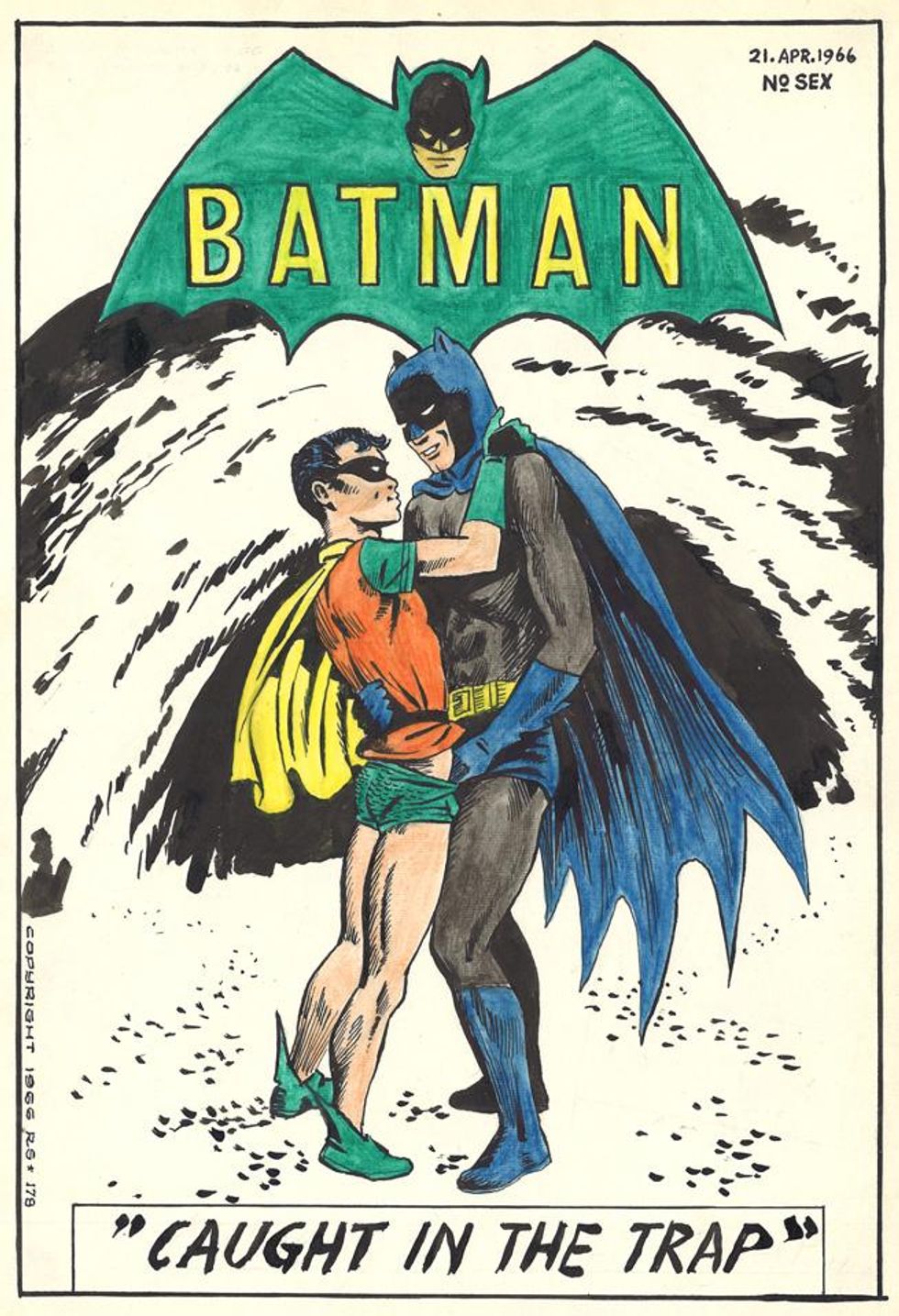

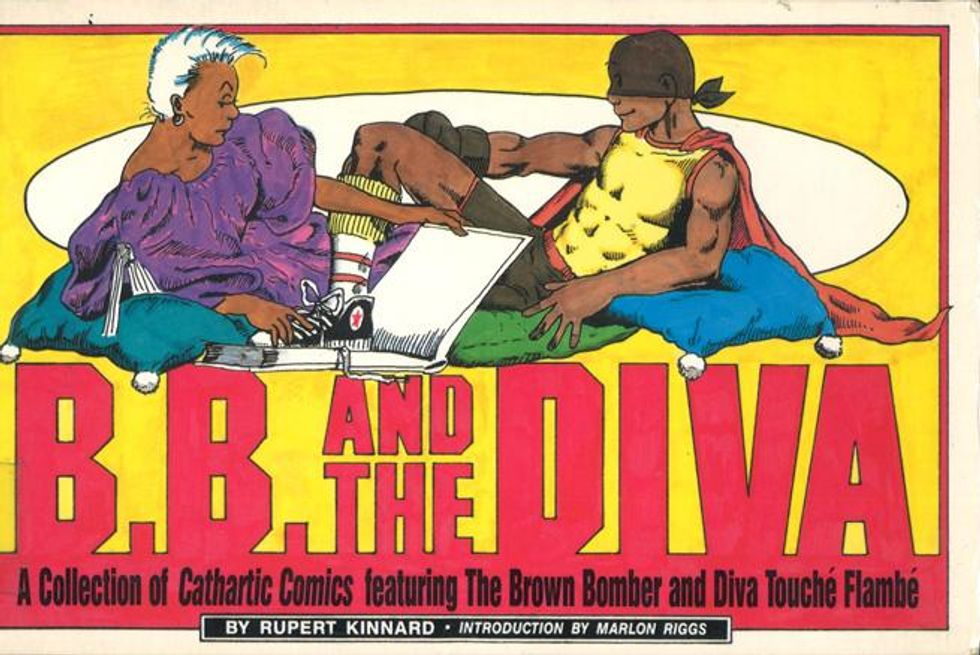

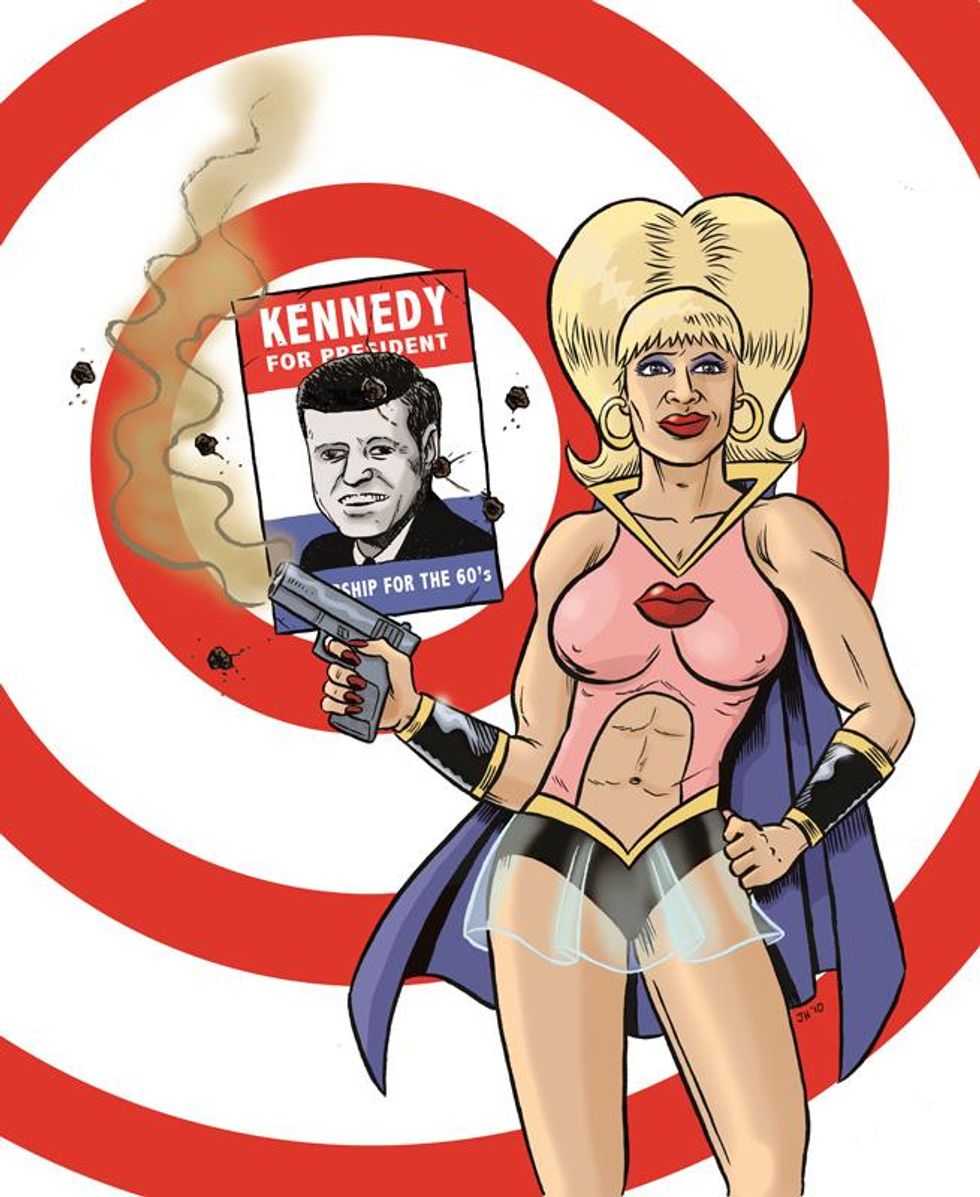

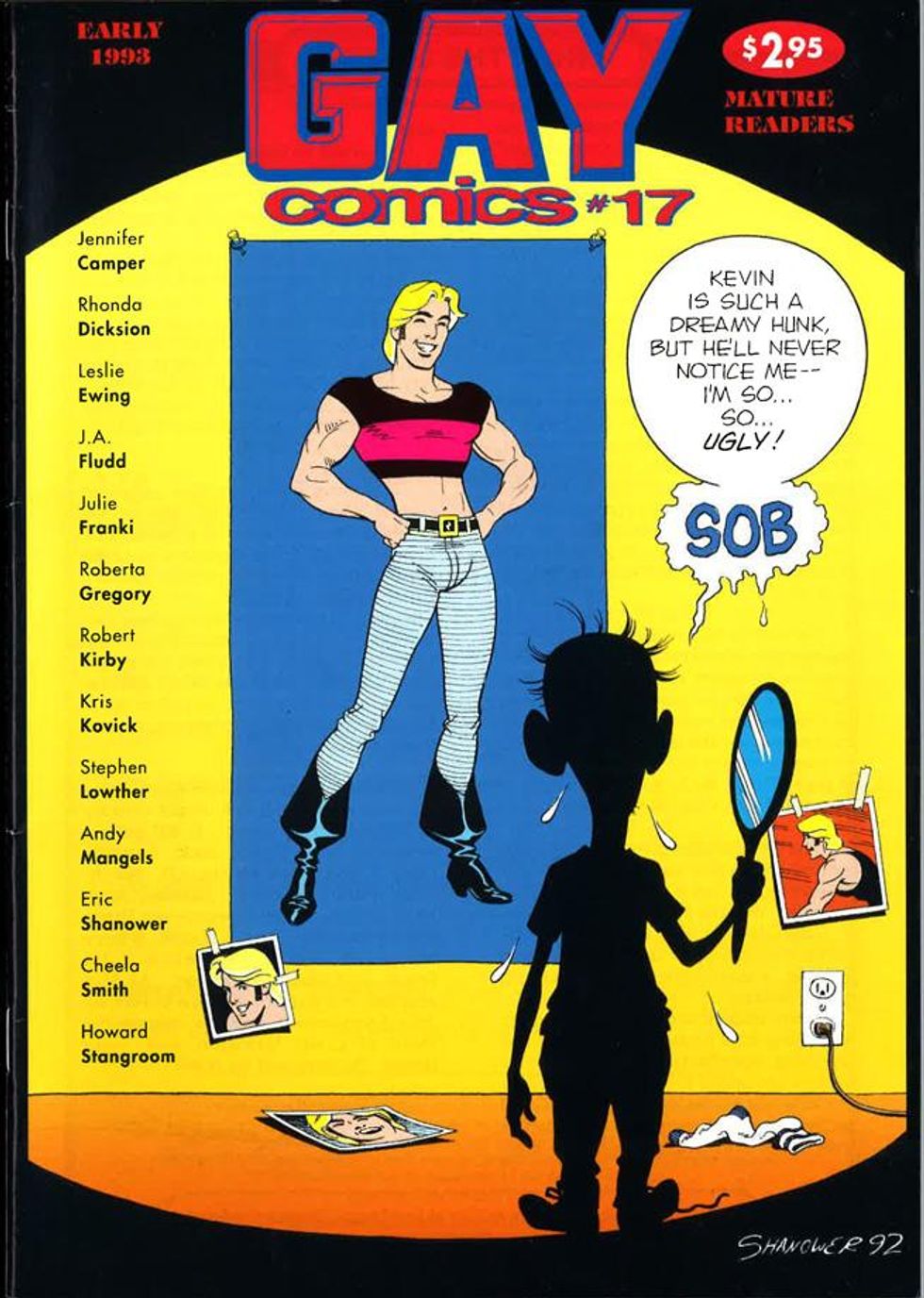

Running through June 2016 at the Schwules Museum in Berlin, the exhibition features depictions of mainstream characters such as the X-Men and Batman families as well as the underground art of queer comics from the fantastic to the everyday lives of LGBTQI people.

Queer comics creator and historian Justin Hall (No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics) is one of the many people who have helped curate the groundbreaking exhibition. Hall recently spoke with The Advocate about the importance of celebrating identities through art, the continued importance of queer comics, and the unique power of the medium.

The Advocate: Why are queer comics still important?

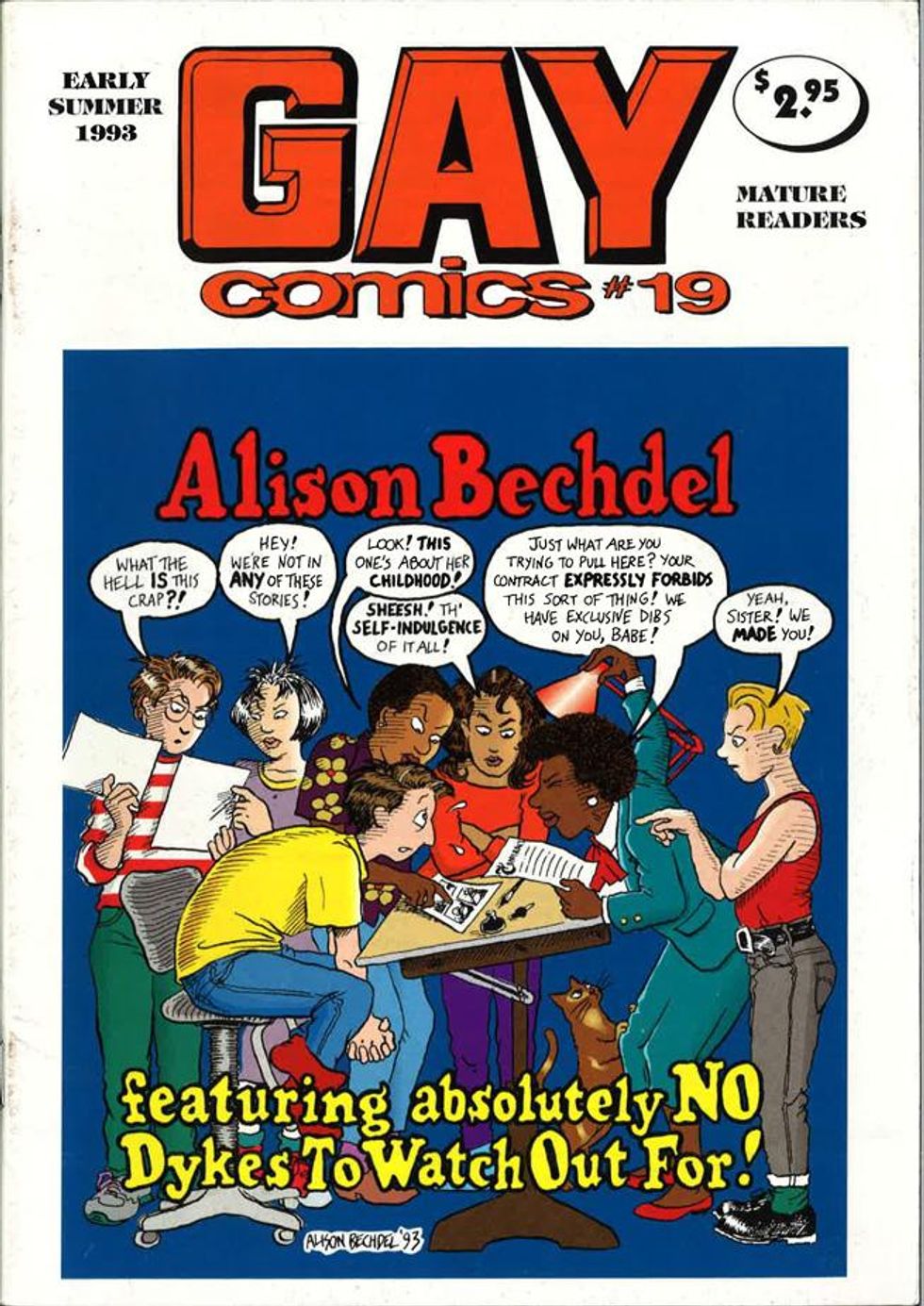

Justin Hall: In the past, comics were one of the few underground DIY mediums in which LGBTQ people could create uncensored stories about their lives. As Alison Bechdel wrote about creating Dykes to Watch Out For in 1983, “I had set out … to make lesbians visible.” And those early comics did that. Now, of course, with societal attitudes changing, you can find lesbians and all sorts of other queer people in everything from superhero comics to Archie comics. … But we still need queer comics! It’s the job of the mainstream to assimilate and normalize queer people, but it remains the job of the queer underground to critique, analyze, poke fun at, and celebrate queer identities and lives from an insider’s perspective.

This is the first museum show in the world to showcase the international breadth of queer comics. What does being a part of its production mean to you?

It’s incredibly exciting to be working with the Schwules Museum in Berlin on this. The show was in part inspired by my book No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics, which attempted to present a history of LGBTQ comics in the Western world; to have a museum of this caliber completely get what I was doing and to expand so profoundly upon it is the most validating and inspiring thing I can imagine! The show adds selections of Japanese manga, superhero comics, and goes into much more depth with German, Italian, and other European comics than I did in my book. I was hoping that my book would be the beginning of a conversation about this material, and this show continues that in a big, international way.

What are some of your favorite aspects of helping curate a show like this?

Working with the museum has been pretty mind-blowing. Even though I’ve curated shows before at the San Francisco Cartoon Art Museum and a couple of local galleries, the scale of this show and the collaboration with the other curators and museum staff and volunteers has made it a unique experience for me. They have a library and archive of queer history here that is incredibly powerful to both view and add to: I got to hold in my hands a first edition of Fredrick Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent, the book which embodied the anti-comics crusade in the U.S. and resulted in the Comics Code Authority. I got to see their extensive collection of queer publications — they have every Advocate ever produced — and walk through their massive basement vault containing everything from homophile manifestos from the 1800s to queer art and photography from all over Europe and beyond. And I’ve been able to talk with my fellow curators about the trajectories of queer comics in other countries, which puts my own knowledge of the North American material in a different perspective and context. I love it when my horizons get expanded so radically!

In what ways can comics further LGBT visibility that other forms of entertainment can’t?

Comics have a unique power to them: They are visual and narrative, but unlike film and TV, they don’t require enormous amounts of resources and collaboration to produce. Mind you, comics are a difficult medium and demand a tremendous amount of creative energy and time, but ultimately it’s the artist’s personal battle with the page. Also, while graphic novels are now being put out by large book publishers, the DIY traditions of comics celebrate cartoonists who put together their comics themselves with a photocopy machine and a stapler or put their work on the Web. With comics creators, as opposed to prose writers, for example, self-publishing is seen as street cred, a badge of honor, and a good entry into the professional comics world.

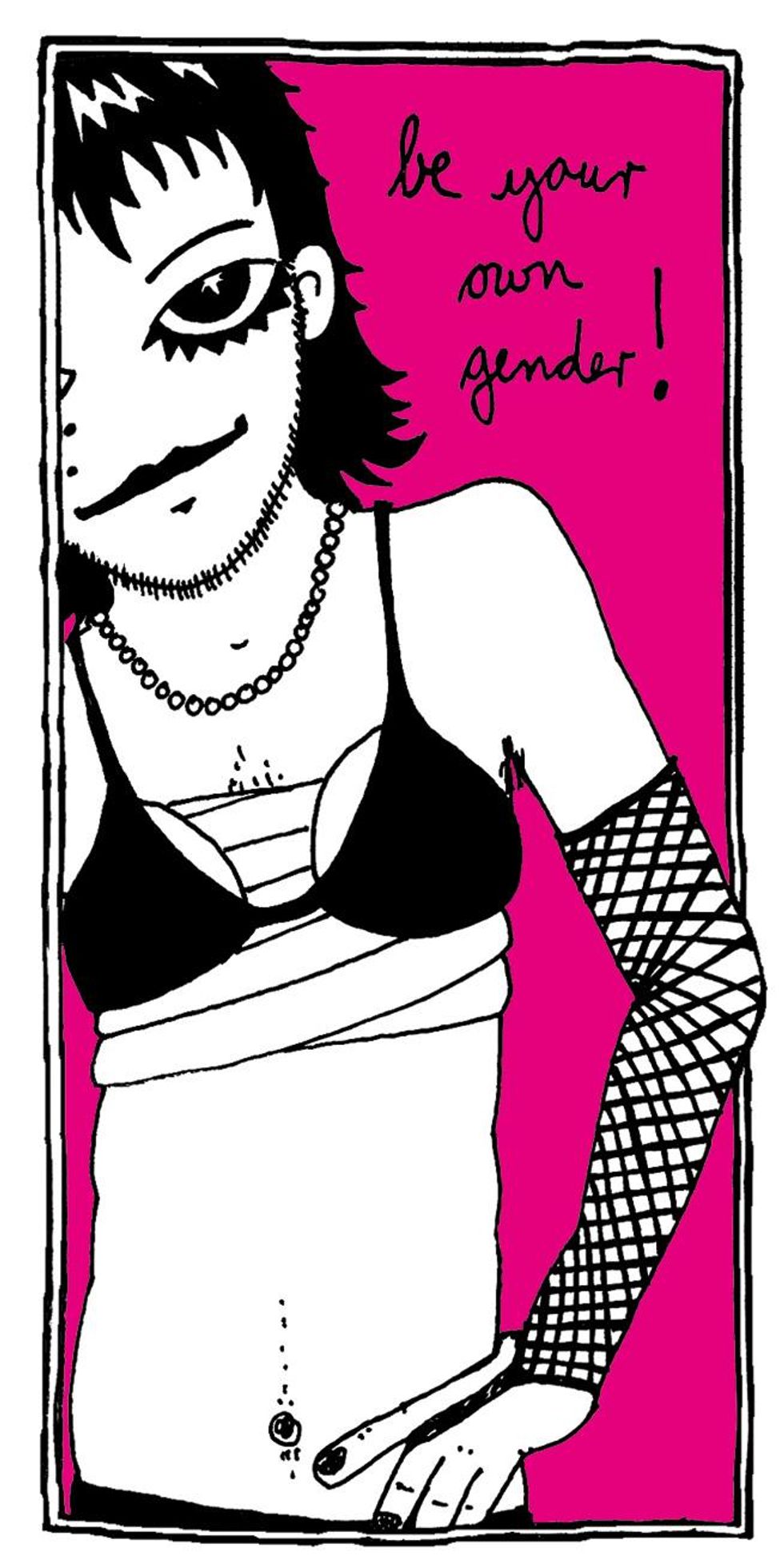

All of this means that comics have an unparalleled ability for producing personal idiosyncratic stories, something incredibly important for LGBTQ people dealing with swiftly changing and complex identity politics, cultural attitudes, and narrative styles. At the same time, comics are, to put it bluntly, just so damn cool. Though they’ve only recently been accepted into the academic world and given more fine art respectability, they’ve always been undeniably popular and have been responsible for a great deal of creative capital over the years, from iconic characters to trend-setting story concepts and visual tropes.

Like LGBT people, the comics medium in America has often been discriminated against as being a “less important” form of art and literature, but other countries have different views on the place of comics in pop culture. What are some of the differences in attitudes towards comics in other places around the world?

France and Japan have long viewed comics as a true form of art and literature, possessing serious cultural weight. On the other hand, France’s comics scene has long struggled with neglect of its female and queer cartoonists; while the Eisner and Ignatz Awards — America’s highest comics honors — were swept by women in 2015, the Grand Prix Angouleme 2016. France’s highest award, put forward a list of 30 cartoonists for consideration … and all of them were men! I don’t know how many of those creators were out LGBTQ cartoonists, but I imagine none or very few.

Other countries represented in the show have less of a comics tradition, but might have different attitudes toward queerness; for example, the most popular German cartoonist is Ralf Koenig, who very openly, graphically, and hilariously chronicles the gay male leather scene in Cologne. In the U.S., with its mainstream dominated by superheroes and children’s comics, Koenig is very much underground. So even though Germany has a much less developed comics scene than in the States, their most prominent comics are pretty much the gayest things ever!

Some have argued that the world of superheroes is innately queer. Would you agree?

Well, there is certainly some obvious sublimated sexuality in imagining muscular, perfectly bodied heroes in skintight outfits flying around grappling with each other, especially since traditionally most of them were male. And as the show points out, there are obvious examples of queer readings of Batman and Robin hanging out in their Batcave together, Wonder Woman living on Paradise Island, populated solely by incredibly attractive and athletic immortal Amazons, and the X-Men, whose powers manifest at puberty and who must deal with a world who hates and misunderstands them. Ramzi Fawaz just came out with his book The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics, which uses queer theory to position superheroes in a conversation with radical politics and countercultural identity in America; these ideas are out there, for sure. That being said, the American comics industry wasn’t the quickest to embrace openly queer superheroes. They’ve come a long way recently, and I’m thrilled to see some of the queer superhero subtext manifested in real, out characters.

Why do you think the genre is embraced by a large number of people around the world while aspects of queer culture, which overlap with aspects of the superhero genre, remain on the fringe?

Superheroes have made huge cultural inroads internationally to be sure, especially since the movies and TV adaptations, but they’re still a distinctly American concept. Still, I agree that adapting different manifestations of heroic ideals cross-culturally is often easier than embracing international queer cultures. The answer to this is in the horrible and tenacious grip that homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, and misogyny has on so much of the world, even to this day. Perhaps as superheroes themselves become more inclusive to queerness, they can help pave the way forward. After all, superheroes at their core are manifestations of our best selves and represent the world as we want it to be.

In what ways would you like to the comics medium move forward in the future?

Comics need to simply continue along the path they’ve been traveling. They need to keep embracing diversity of content, platforms — Web comics are the future! — characters, readers, and creators. They need to talk about our real lives as well as our fantasies. They need to tell stories that inspire us to live in the world that we all deserve.

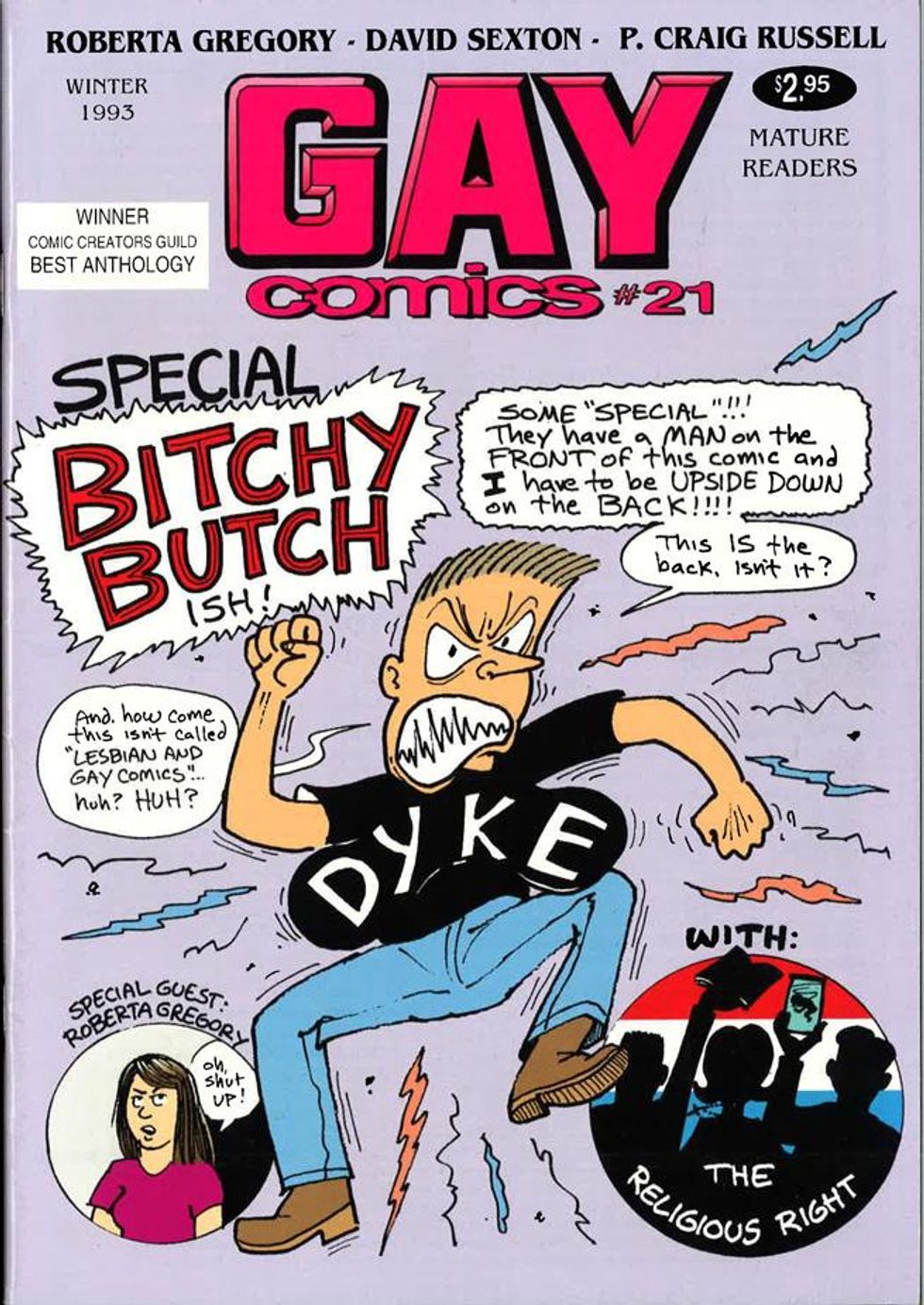

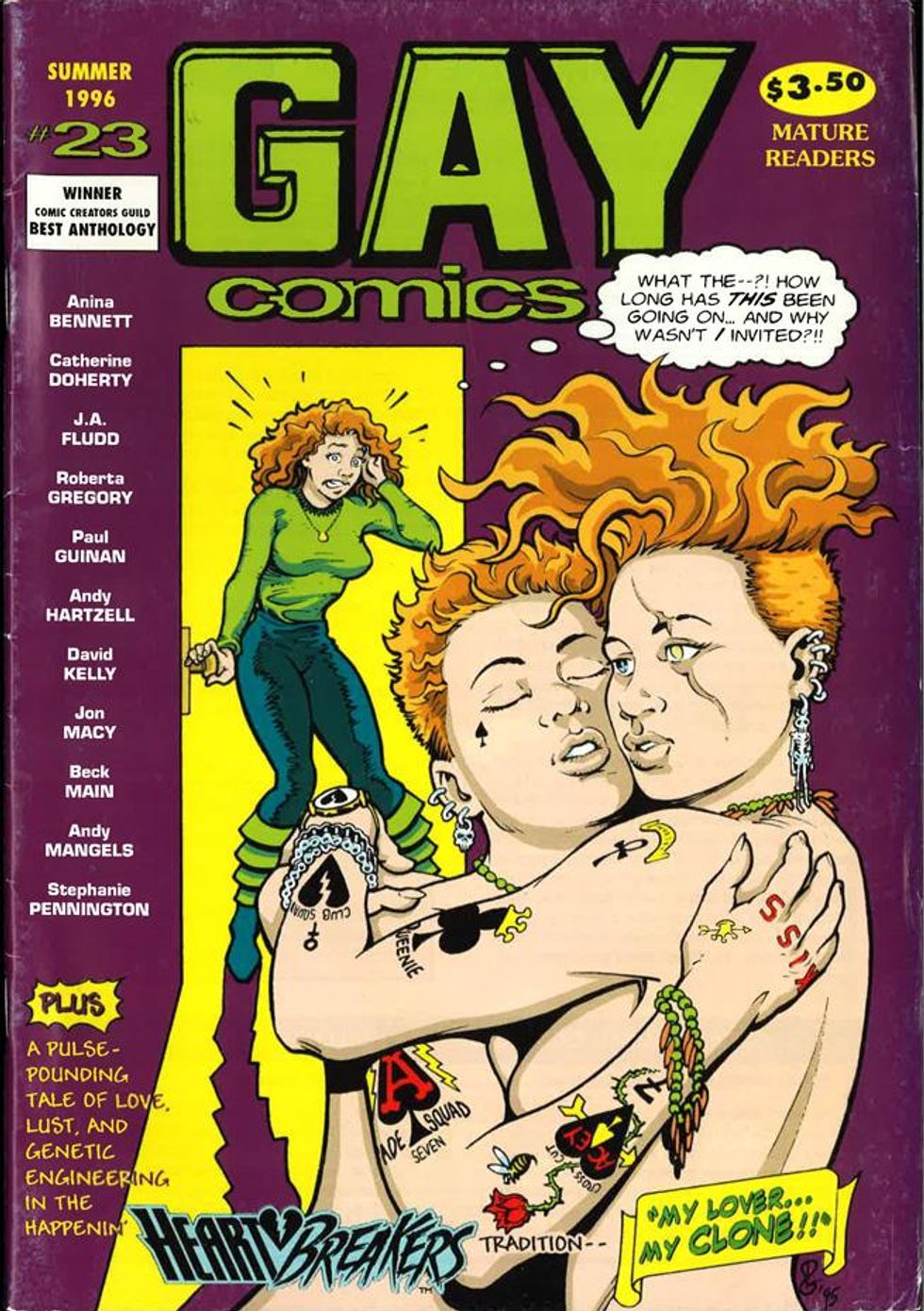

View a selection of the art that will be displayed at the "Superqueeroes" exhibit in the accompanying slideshow, and for more on Justin Hall, visit his website and follow him on Twitter.

More Galleries

12 movies to watch if you loved ‘Red, White & Royal Blue’

October 27 2025 6:02 PM

LGBTQ+ History Month: 33 queer movies to watch on streaming

October 02 2025 9:02 AM

Drag Me to the Catskills: A weekend of camp and comedy in the woods

May 29 2025 8:30 PM

Boys! Boys! Boys! podcast: A new voice in queer culture

May 01 2025 5:03 PM

Cobblestones, castles, and culture: Your LGBTQ+ guide to Edinburgh

April 30 2025 12:44 PM