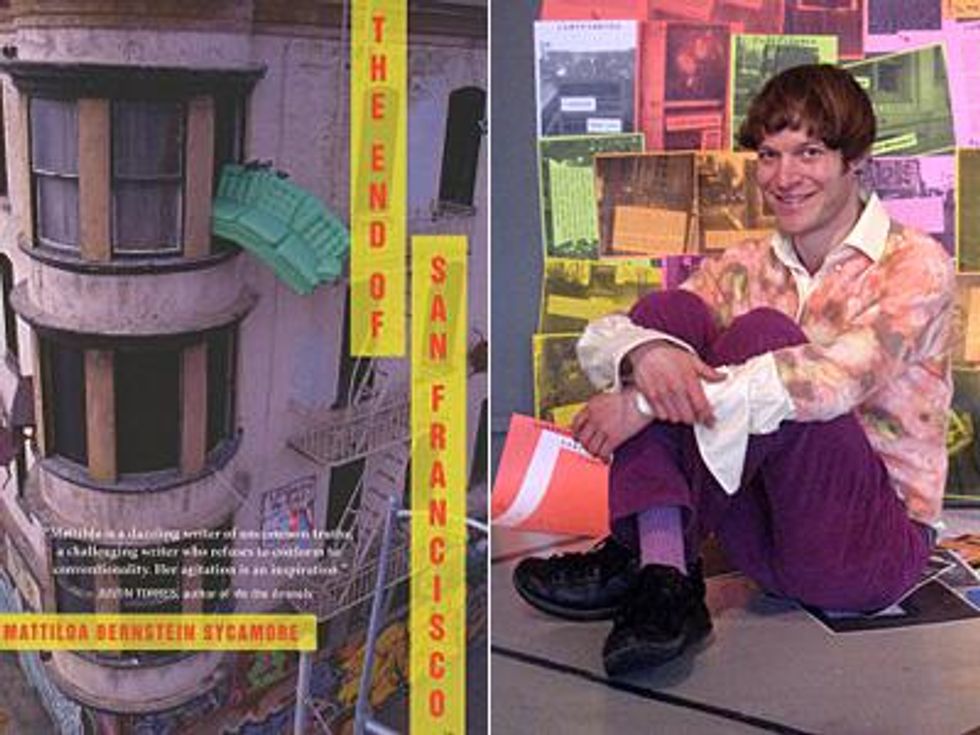

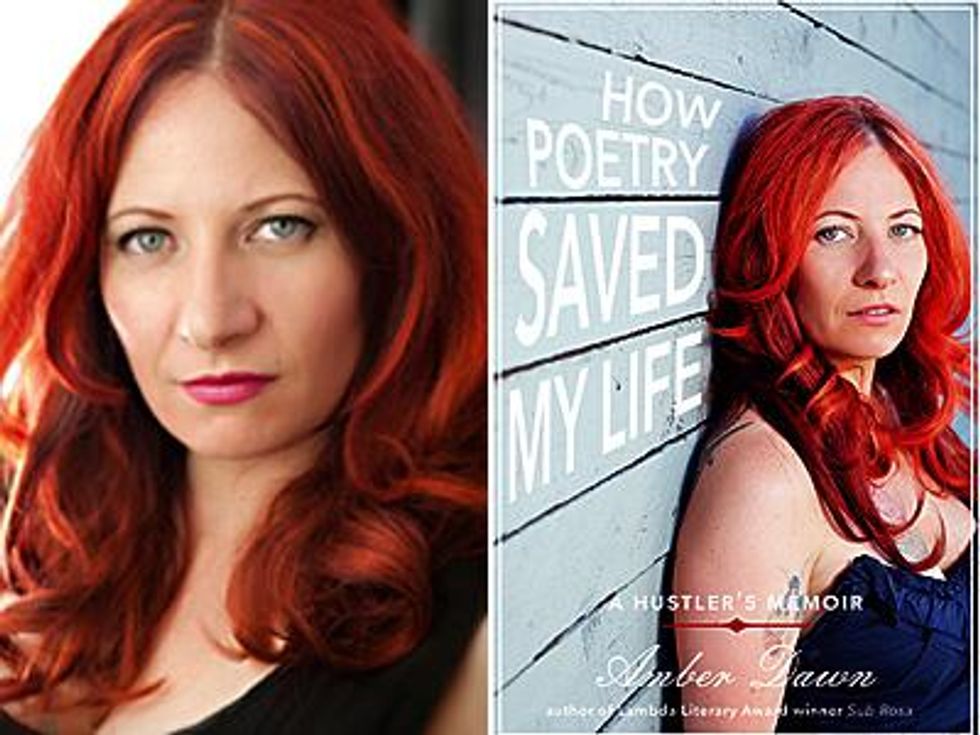

Amber Dawn and Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore met each other nearly a decade ago, at a Vancouver bar where Dawn was performing an original piece about her life as an out queer sex worker. Since that fateful evening, the authors' paths have crossed repeatedly, whether they're finding mutual friends in the queer community, dissecting the intricacies of sex work and survivorship, or, in the case of this author conversation, relating over their respective newly released memoirs. Sycamore's third and newest book, The End of San Francisco, is now available through City Lights. Dawn's sophomore novel, How Poetry Saved My Life: A Hustler's Memoir, is available now through Arsenal Pulp Press. Read on for a revealing discussion on identity, upbringing, and finding your way "home."

Amber Dawn: I love the title of your new book, The End of San Francisco, and what it says about queer identity and location.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore: San Francisco has been the most formative place for me -- politically, socially, sexually, emotionally. I first moved there in 1992, when I was 19, and it's really where I learned how to create community and culture and love and lust and intimacy and activism on my own terms. It's also the place that has let me down the most -- in such brutal and heartbreaking ways.

Dawn: Ah! Our dates are aligning. I moved to Vancouver in 1992, when I was 18, and -- just like you -- feel that my location has taught me countless lessons. My new book is as much about Vancouver as it is about my identity as a queer, sex worker, survivor, and poetry lover.

Sycamore: I love that we're about the same age. The first time we met, you were hosting a performance night at a bar in downtown Vancouver, and I came through on the book tour for my first novel, Pulling Taffy -- that was 10 years ago. One great thing about rapidly approaching 40 is that now I can talk about something 10 or 15 years ago, and it can still be away from the suffocation of childhood and my parents and everything I was supposed to be.

Sycamore: I love that we're about the same age. The first time we met, you were hosting a performance night at a bar in downtown Vancouver, and I came through on the book tour for my first novel, Pulling Taffy -- that was 10 years ago. One great thing about rapidly approaching 40 is that now I can talk about something 10 or 15 years ago, and it can still be away from the suffocation of childhood and my parents and everything I was supposed to be.

Dawn: "Suffocation of childhood" -- I can relate to your wording. The way you articulated returning to your childhood home in your opening chapter is tremendously keen, and so close to the bone for me. It is a much easier task for me to write about adulthood. In my own book, I attempt teenage memoir and write about my first queer love experience, set in my dead-end town. I'm from Crystal Beach, Ontario, an impoverished community of about 4,000 permanent residents along Lake Erie, across from Buffalo, N.Y. It was an amusement park town for 100 years, but the park closed in 1989 and Crystal Beach virtually became a ghost town. So I came from a failed amusement park community -- the only daughter of my draft-dodging father and hippie mom, two dreamers who ultimately felt their love-generation dream failed. Failure was part of my upbringing. Therefore, my first glimpse of Vancouver -- and of a city with an established queer community -- was through the eyes of a defeated, angsty, small-town girl. Through those eyes, Vancouver was rife with possibilities.

Sycamore: I grew up in an upper-middle-class assimilated Jewish family in suburban Washington, D.C., in a different kind of failure most people call "success." I was sexually abused by my father, and it was his financial and professional success that allowed my parents to camouflage their violence. I went to an elite East Coast university in order to get away, but then I realized I was just learning how to beat my parents on their terms, so I fled to San Francisco after a year to find other queer freaks and outcasts, incest survivors and vegans and anarchists and drug addicts and activists. That was one thing I wanted to say about that night 10 years ago when you and I first met: I could see several of the worlds that meant something to me colliding in that space -- sex work and club culture and drugs and writing and surviving. I think that's one of the things that's similar in our work, trying to make sense of these connections that are so clear in our individual lives but don't make sense to a lot of people, or make too much sense.

Dawn: For a short I while kept my worlds separated, especially the queer and sex trade worlds. I couldn't maintain the division. When I was first working on the street I was so young and vulnerable; I didn't even have a cell phone yet. It was rough trade. I needed to disclose to queer friends and lovers for safety reasons -- even if it made them anxious for me or caused friction. By the time I moved into indoor sex work at 25, I was completely out about sex work and survivorship. I had already begun to write and perform about it -- like at the show in Vancouver where you and I first met. That show was actually at an infamous strip club called the Penthouse. In the 1940s it was one of the only venues that showcased people of color performers. So we performed in the same room as Sammy Davis Jr., Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Carmen Miranda -- and scores of burlesque dancers. Little did you know you were at one of Vancouver's most interesting historic locations!

Dawn: For a short I while kept my worlds separated, especially the queer and sex trade worlds. I couldn't maintain the division. When I was first working on the street I was so young and vulnerable; I didn't even have a cell phone yet. It was rough trade. I needed to disclose to queer friends and lovers for safety reasons -- even if it made them anxious for me or caused friction. By the time I moved into indoor sex work at 25, I was completely out about sex work and survivorship. I had already begun to write and perform about it -- like at the show in Vancouver where you and I first met. That show was actually at an infamous strip club called the Penthouse. In the 1940s it was one of the only venues that showcased people of color performers. So we performed in the same room as Sammy Davis Jr., Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Carmen Miranda -- and scores of burlesque dancers. Little did you know you were at one of Vancouver's most interesting historic locations!

Sycamore: I love that history -- I remember the night of that show there were some rowdy drunk white men in the back yelling "faggot" at me while I performed, and everyone was embarrassed, but I thought it was kind of funny. It's those somewhat uncomfortable intersections that mark both of our lives as writers and performers and hookers, offering a sort of structure, right?

Dawn: Well, I'm no expert on structure. Ironically, for all my outspokenness on the topic of sex work, and for all my ability to bring together my communities, I've never written the customarily structured memoir. The idea of writing a single, chronological narrative about my experience is daunting. Instead, I would write a short memoir story or a poem to perform on stage and then "shelve it." Eventually I had a book's worth of work on the "shelf." Even still, it took a lot of courage for me to go back to that work and edit it all into How Poetry Saved My Life. I do not fear telling my story on stage at a spoken-word show. If I can see my audience face-to-face I can say almost anything ... But publishing it in a book? The risk is still palpable for me.

Sycamore: That's interesting, because I do feel like choosing to call The End of San Francisco nonfiction has made me feel more vulnerable, even though -- and maybe because -- the book is structured more like an experimental novel than a memoir. But I'm calling it memoir because I keep circling around my formations and their undoing. It's not that the things in my novels didn't actually happen to me, because mostly they did, but what I choose to focus on is very different. I think in a conventional memoir everything is kind of whitewashed towards an inevitable triumphant conclusion. In The End of San Francisco, I wanted to avoid that at all costs by keeping in the contradictions, the places where my analysis stops, the broken moments, the uncomfortable juxtapositions between past and present and future. That feels more honest and vulnerable to me.

Dawn: Speaking of honesty, when writing about the city that essentially raised up your queer self, did you realize anything unexpected?

Sycamore: One of the things I realized while writing The End of San Francisco was how much I believed in these worlds that are always letting me down, over and over again, but I keep believing. One of the most heartbreaking moments in the book happens in 1994, just a few years after I moved to San Francisco -- it's when I first realized that I could never again believe in something called "community." In this case, it was a culture of dykes and a few fags in a specific neighborhood in San Francisco, the Mission. I really believed that we were creating a radical alternative to the status quo, but then I saw the way that people treated each other just as badly. Worse, maybe. I'm still haunted by this realization. Over and over again I'm haunted.

Dawn: I certainly never want to return to my formative queer years -- to my late teens and early 20s. I'm often nostalgic for those days, but I remember the utter lack of communication and safe coping skills many of us had. There is a poem in my new book where I admit to hitting my high-school girlfriend with a phone receiver, to which she replies, "Cocaine is turning you into an asshole." This is one example in the book where I frankly disclose being a part of the violence, the misogyny, the racism, and all the various ways we disregard or fail to see one another within our communities. I hope that if I call myself out with honesty that it will help reinforce the idea that we can all call each other out. Our values ultimately suffer when not calling each other to accountability becomes a pattern. It's a farce to think that queers can be highly visible for all the "fabulous" things that we are but then invisibilize our flaws. We need to look at ourselves and our communities in a more holistic way.

**

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore has been described as "a cross between Tinkerbell and a honky Malcolm X with a queer agenda" by the Austin Chronicle, and as one of "50 Visionaries Changing Your World" by Utne Reader. Sycamore is the author of two novels, So Many Ways to Sleep Badly and Pulling Taffy, and the editor of five nonfiction anthologies, most recently Why Are Faggots So Afraid of Faggots? Flaming Challenges to Masculinity, Objectification, and the Desire to Conform, winner of an ALA Stonewall Book Award this year. Sycamore is also the editor of Nobody Passes: Rejecting the Rules of Gender and Conformity and That's Revolting! Queer Strategies for Resisting Assimilation. She writes regularly for a variety of publications, including the San Francisco Bay Guardian, Bitch, Bookslut, Alternet, and Time Out New York, and is the reviews editor at the feminist magazine Make/shift. She lives in Seattle.

Amber Dawn is a writer, filmmaker, and performance artist. She is the author of the Lambda Award-winning novel Sub Rosa and editor of the queer anthologies Fist of the Spider Woman: Tales of Fear and Queer Desire and coeditor of With a Rough Tongue. Her award-winning, genderfuck docu-porn, Girl on Girl, was screened in eight countries and added to the gender studies curriculum at Concordia University in California. Until August 2012 she was director of programming for the Vancouver Queer Film Festival.

Sycamore: I love that we're about the same age. The first time we met, you were hosting a performance night at a bar in downtown Vancouver, and I came through on the book tour for my first novel, Pulling Taffy -- that was 10 years ago. One great thing about rapidly approaching 40 is that now I can talk about something 10 or 15 years ago, and it can still be away from the suffocation of childhood and my parents and everything I was supposed to be.

Sycamore: I love that we're about the same age. The first time we met, you were hosting a performance night at a bar in downtown Vancouver, and I came through on the book tour for my first novel, Pulling Taffy -- that was 10 years ago. One great thing about rapidly approaching 40 is that now I can talk about something 10 or 15 years ago, and it can still be away from the suffocation of childhood and my parents and everything I was supposed to be. Dawn: For a short I while kept my worlds separated, especially the queer and sex trade worlds. I couldn't maintain the division. When I was first working on the street I was so young and vulnerable; I didn't even have a cell phone yet. It was rough trade. I needed to disclose to queer friends and lovers for safety reasons -- even if it made them anxious for me or caused friction. By the time I moved into indoor sex work at 25, I was completely out about sex work and survivorship. I had already begun to write and perform about it -- like at the show in Vancouver where you and I first met. That show was actually at an infamous strip club called the Penthouse. In the 1940s it was one of the only venues that showcased people of color performers. So we performed in the same room as Sammy Davis Jr., Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Carmen Miranda -- and scores of burlesque dancers. Little did you know you were at one of Vancouver's most interesting historic locations!

Dawn: For a short I while kept my worlds separated, especially the queer and sex trade worlds. I couldn't maintain the division. When I was first working on the street I was so young and vulnerable; I didn't even have a cell phone yet. It was rough trade. I needed to disclose to queer friends and lovers for safety reasons -- even if it made them anxious for me or caused friction. By the time I moved into indoor sex work at 25, I was completely out about sex work and survivorship. I had already begun to write and perform about it -- like at the show in Vancouver where you and I first met. That show was actually at an infamous strip club called the Penthouse. In the 1940s it was one of the only venues that showcased people of color performers. So we performed in the same room as Sammy Davis Jr., Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Carmen Miranda -- and scores of burlesque dancers. Little did you know you were at one of Vancouver's most interesting historic locations!