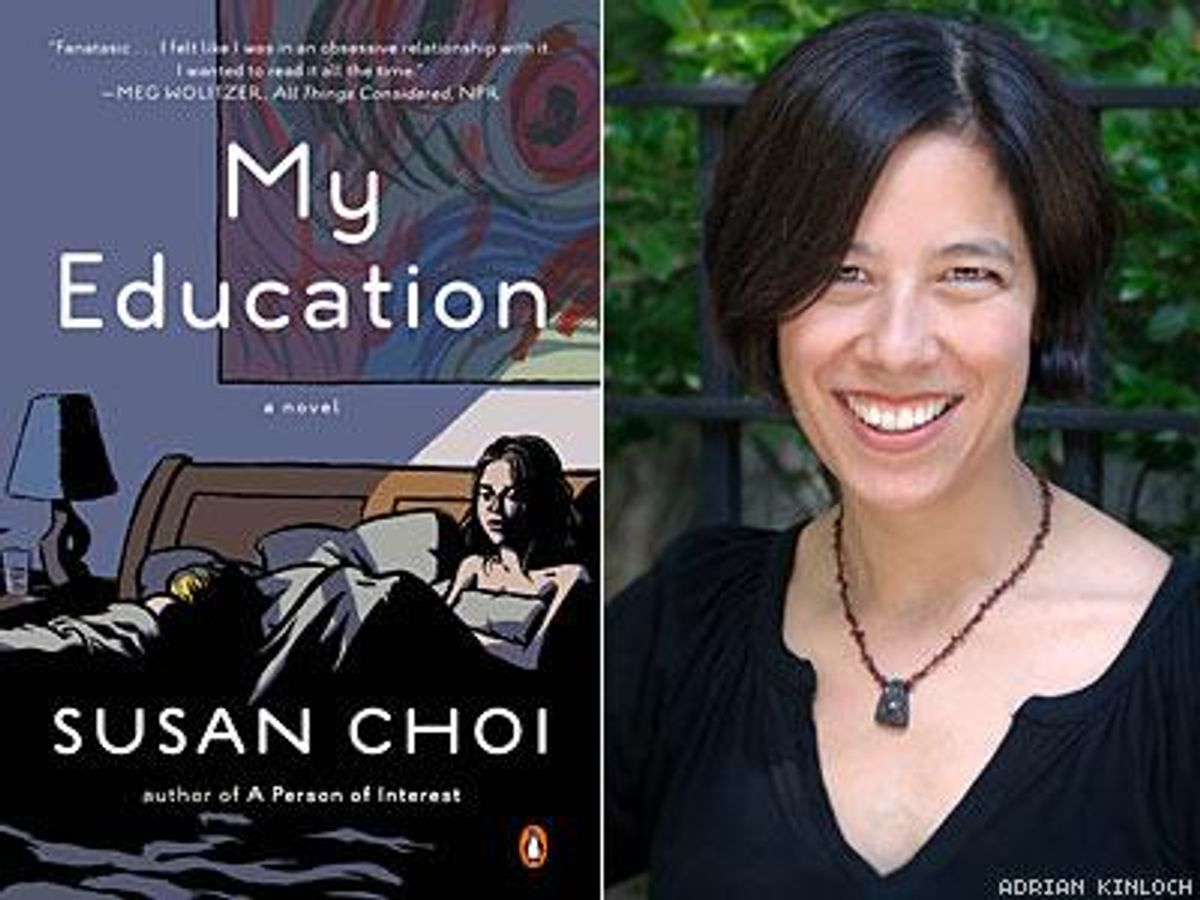

According to Lambda Literary, Susan Choi's book My Education is the best bisexual novel produced this year. Read an exclusive excerpt from the book below.

June 19 2014 5:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

According to Lambda Literary, Susan Choi's book My Education is the best bisexual novel produced this year. Read an exclusive excerpt from the book below.

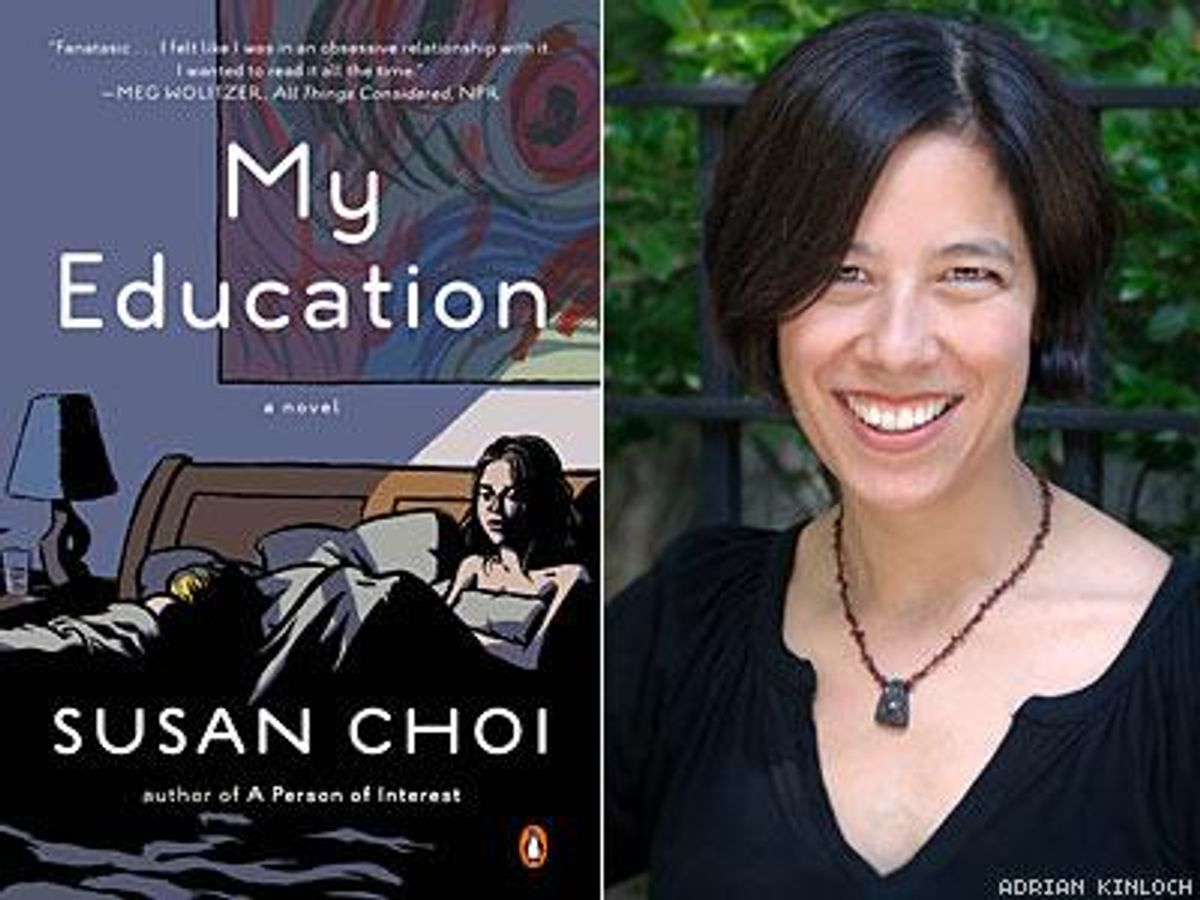

Susan Choi is the author of four novels, including the Asian American Literary Award winner The Foreign Student, PEN/Faulkner Award Finalist A Person of Interest, and Pulitzer Prize finalist American Woman, as well as co-editor (with David Remnick) of Wonderful Town: New York Stories from the New Yorker. Choi is the recipient of Guggenheim and NEA fellowships and the PEN/W.G. Sebald Award, and teaches creative writing at Princeton. Last month her latest novel, My Education, won the Lambda Literary Award for Best Best Bisexual Fiction.

The novel follows graduate student Regina Gottlieb, who arrives at her presigious university and encounters the provocative Professor Nicholas Brodeur who, she is warned, "lie[s] in the dark in his office while undergraudate women read couplets to him" and is "condemned on the walls of the women's restrooms" on campus. She gravitates toward him, then becomes enraptured with Martha, his even more charismatic, volatile wife, beginning an intense, devastating "education" in the bedroom which reverberates throughout her next fifteen years.

After winning this latest honor bestowed by the authors and editors who make up Lambda Literary's voting members, Choi agreed to provide The Advocate with an exclusive excerpt from My Education.

Read it below.

I hadn't slept well the previous night. Until now I had never had problems with sleeping, but since my concussion, and especially nights I was staying at Martha's, I'd often found myself awake at two or three in the morning, sleep snatched from me so abruptly that no drowsiness softened the onslaught of fretful alertness. I would wonder, made anxious by Dutra, if this was some tardy response of my body, defending me, after the danger, from succumbing to coma. I suspect that what really awoke me was surfeit--of the elation of having won Martha, and the terror of it; of satiation, my mouth webbed with sap and my tongue paralyzed with fatigue; and for some reason grief, as if I already knew I could never possess her enough. All in surfeit, beyond what I'd ever contain or endure, as I lay close to her in the dark. Her thin flank in slumber, hitched up, sometimes pinioned my hips. Her breast hung as if tucked in the fold of her arm, and subsiding from there to the curve of the other. Sometimes she looked older when she slept. Then the horror of her mortality, as if it were an unjust curse on her and me alone, would demolish my pride and restraint, and with a convulsion as unwilled as willed I would jostle her roughly so that she woke up. Sometimes, as if we'd arranged it that way, we would lavishly fuck. Sometimes, with a groan, she would tell me to get up and read, or to finish the joint on her dresser. One time we fought--"You are so fucking selfish!" she snarled. But the risk of that wound was offset by the prospect of love. By one side of her mouth rising up in the way that she had of attributing great wicked slyness to me, as she roughly un- zipped me and spilled out my fear so that sleep could return.

Other nights, I never woke her at all but slipped silently out of her bed. Then her home would seem alien to me, its own elaborate nitrogen cycle. Those six doors on the second-floor hall: her own; the former master bedroom that now served as her study; the former study of Nicholas's that was now a guest bedroom; the former "library" which was dedicated now to the transient, to boxes being packed or unpacked; and past the stairwell at the opposite end, the corner rooms belonging to Anya and to Joachim. And an entire "stand up" attic above, and then the slovenly grandeur below, the vast kitchen and breakfast nook, the only rooms on that floor that seemed wanted and used; and then the formal dining room and living room and den and the entry foyer with their dust-pale refugee camps of side chairs and armchairs and side tables and end tables and sideboards and "consoles" and other words that would sometimes scud past that I had never yet linked to an object. At that time of my life I had no understanding at all of such houses as these, of the process by which they come mushrooming all on their own from the compost of cohabitation. I had no experience of adult sediment, no experience of that chemistry of domesticity by which x, which is love or its likeness, becomesy, which is not quite the same, becomes z, which is more different yet, to the point that sustains, or that smothers and kills. The twelve years she had over me, thirty-three to my wise twenty-one, meant no more to me than the one year Joachim had just recently notched on his belt. Had those twelve years separated us later in life--my thirty-seven from her forty-nine; my forty from her fifty-two-- this blindness, which was really the thoughtless belief in our sameness, might have been apt. But it was treacherous now, so much so that despite my complete ignorance of how little I knew, I intuited somehow my weakness. I knew her house was strange water to me, when I bobbed there alone.