Screenwriter Barry Sandler discusses the 1982 gay-themed drama, actors who refused to star in it, and its lasting legacy.

July 14 2012 2:28 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

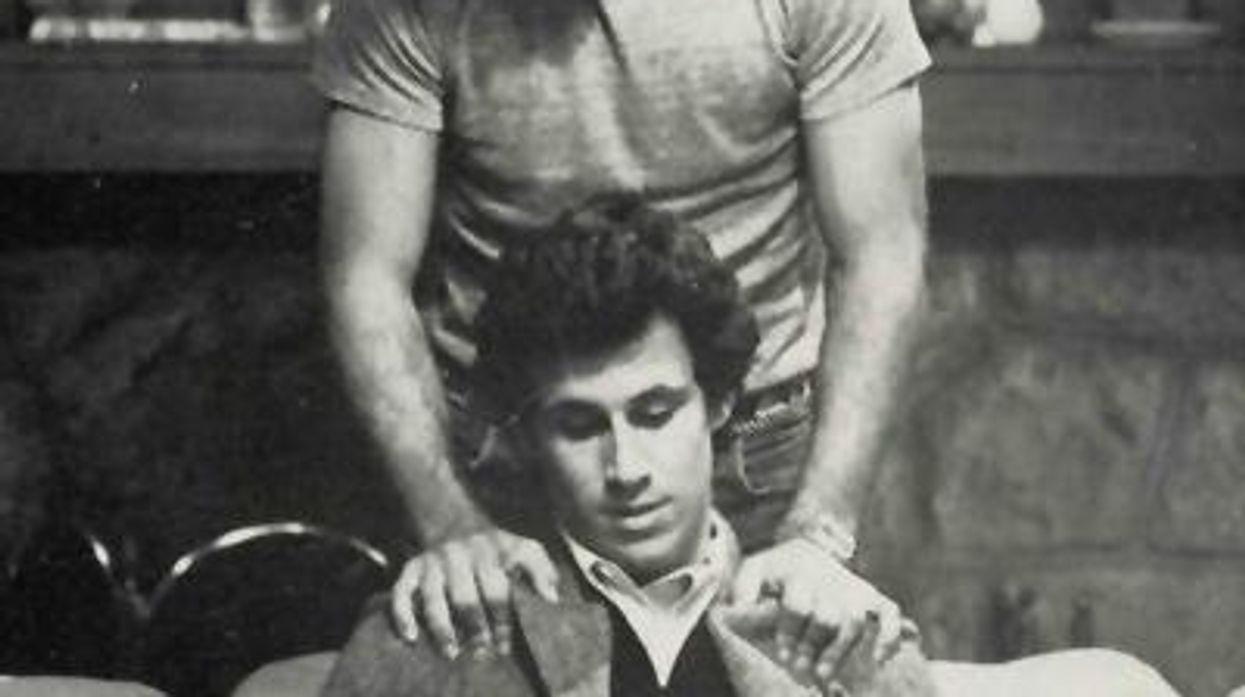

Screenwriter Barry Sandler was ready for a challenge. By 1980, Sandler had racked up an impressive resume of glossy mainstream credits that included the romantic biopic Gable and Lombard, the Raquel Welch roller derby vehicle Kansas City Bomber, and the all-star whodunnit Evil Under the Sun. The time had come for him to write something more personal. With the encouragement of his then-boyfriend, writer A. Scott Berg, Sandler penned the screenplay for Making Love, about a married doctor (Michael Ontkean) who comes out to his wife (Kate Jackson) after an affair with a gay writer (Harry Hamlin). As the hugely anticipated release of the semi-autobiographical film, regarded by many as the first studio movie to treat gay people respectfully, approached, Sandler knew he'd need to be open about his being gay. In an interview with The Advocate at the time, he spoke about how liberated he felt. "Once you acknowledge to the world, once there are no more secrets, you're no longer concerned about going to a party with another guy. I don't give a shit anymore. This is who I am." Sandler, who now teaches screenwriting at the University of Central Florida, would go on to write numerous other films, including the electrifying Ken Russell-Kathleen Turner collaboration Crimes of Passion, which he is planning to mount for the stage. The GLAAD Award-winning writer speaks with The Advocate about the 1982 film, reveals which actors refused to star in it, and shares what he sees as its legacy.

The Advocate: What inspired you to write Making Love?

Barry Sandler: I was involved in a relationship with Scott Berg, and it was around the late '70s-early '80s, and I was sort of reassessing where I wanted to go as a screenwriter. I had done a number of films that were more glossy and Hollywood. These were films that really didn't challenge me in terms of who I was and where I wanted to go, you know, probing complex themes that I was looking to do. Scott was really instrumental in getting me to dig deeper and he really thought it would be a good, not really a challenge, but to do the first gay-themed film to come out of Hollywood that shows a positive portrayal of gay people. It had never been done before, and ... have you ever seen The Celluloid Closet?

Many times.

I'm in that film, so we talk about it. Whenever a film depicted gay people, they were either the butt of jokes or comic figures to laugh at or suicidal or desperate or pathetic. Growing up and being inundated with those kind of gay images, it forced a lot of people into the closet or else they grew up with a feelings of fear or shame or guilt or unwillingness to admit to who or what you are. With Scott pushing me and my own conscious need as a writer to probe deeper and also, you know, the idea of writing a movie that would hopefully, if not reverse the trend, certainly be a breakthrough in terms of depicting gay people as real human beings who go through, you know, who are recognizable and identifiable, and who have the same kinds of needs and problems as anyone else, and most importantly can accept our identity and live a happy, successful, gratifying life, accepting who you are, being honest with who you are, and I thought that was a very, very important movie in 1982 to make.

It was certainly groundbreaking.

It had never been done before, and I knew that it was going to be a difficult time trying to get it going, which, ironically enough, it really wasn't. But as for what propelled me or inspired me to write it, it was a number of things. It was Scott pushing me, it was my own reassessment of where I wanted to go as a writer, and it was also I felt a need to make a positive statement that hopefully the next generation of young gay and lesbian men and women coming up would have something a little more positive to look at on the screen that could help them feel a little better about who they are and possibly not necessarily not have to hide in the closet. Now, I'm not trying to sound humanitarian or anything like that, but I just felt since I am a creature of the movies, growing up in the movies, and because we do get so much of our sensibilities are so shaped by what we see in the media, and this is really before cable TV and all that, but by images and film and books and television, and I felt I could utilize whatever talent I have as a screenwriter to possibly shape or make an impact or shape human attitudes.

What was the studio's initial reaction to the screenplay?

The fear was that in 1980, which is when it was written, it was the beginning of a conservative era. Reagan was about to be elected and I felt the odds were probably against us for getting this film made, and I said I don't want to go out on a limb and write this thing and not have anyone want to make it. Because, you know, studios are notoriously gutless when it comes to doing anything dealing with ... well, they certainly were then ... doing anything with sex or sexuality or anything that might be perceived as subversive. Scott was very close with Claire Townsend, who was head of development at 20th Century Fox right under Sherry Lansing, and the irony is it was two women. Sherry ran the studio, and Claire was one of her people in command in development who really got the movie off the ground. We went to Claire and then to Sherry and said, "This is the movie. If the script turns out, would you be willing to make it?" And they said, "Yes, absolutely." And I had enough confidence that the script would turn out, but I needed the assurance that if it did, they would make it. And Sherry did say, "Yes we want to make this movie." I don't know if a male head of a studio - straight, gay, or indifferent - would have made this movie, but really I think it took a woman in 1980 to be able to say, "Yes, I'm going to make this movie."

What happened after Sherry agreed to make it?

I went off and wrote it. I mean, Scott and I hammered out the story, and then I went off and wrote it. And then, we did a second draft, and we turned it in, and almost immediately, they jumped at it. Danny Melnick, who was a big producer at the time, had done a lot of big movies, like Altered States, Close Encounters, and All That Jazz, came aboard Fox and read the script, called me at 1 in the morning, and just said he loved the it. He was very moved by it, and I mean this great guy, this great producer, said, "I want this to be my first movie at Fox."

Arthur Hiller, who was very prominent at the time, having done Love Story and Hospital and The In-Laws and a number of big movies, Sherry had a relationship with Arthur and gave him the script and he loved it, and he came aboard very quickly, so getting a director was no problem. He jumped on it, and I met with him. And he was terrific and very receptive to the script and wanted to make that movie. And you know, had very little changes. Minor stuff.

How different was your script from what ended up on-screen?

There were only script changes that any writer would have with any director, like maybe, this scene might be a little too long or maybe we don't need this scene or maybe we can consolidate this into that. Nothing, absolutely nothing, dealing with the gay issue. It was only script mechanics. There was one long scene with Michael Ontkean's character with his brother that was good, but it really kind of took the film in a slightly different direction, that we felt could be cut. So it was more just tightening the script and getting it down to a shooting length. That sort of thing.

So you hadn't written any more explicit love scenes?

Oh, no, no, no. Those were all filmed as written pretty much. Casting was pretty interesting too.

Naturally, any studio wants to start off by going after big stars, and at that time it was still before it was fashionable to play gay. So they went out to a number of big stars who turned it down. We said, "Look, the star of the movie is really the subject. So people are going to come to see the movie or not come see the movie, I think, based on the subject." Yes, the star might draw them in, but more importantly, we wanted to get the best actors we can. And that's how we got Michael and Harry. Kate Jackson was, you're probably too young to remember this, she was one of the original Charlie's Angels.

Oh, I remember.

And she was a big household name. I mean, Charlie's Angels was a big, big deal. She's a television name. But Danny Melnick had a really good thought. I remember they approached Goldie Hawn at one point, who was a huge movie star. Actually, I'd worked with her a couple of years prior to that [on the western-comedy The Duchess and the Dirtwater Fox]. And I was on the phone with her, and she had read the script. She said, "Look, she said, it's a really good script, and it's a good part, but I can't do this movie." She said, "First of all, you don't want to make this a Goldie Hawn movie. The star of the movie is the two guys. The wife is an important part, but, you know, it's really the guys' movie. And if I did it, it would become a Goldie Hawn movie, and you don't want that."

That's smart and the best pass on a movie I've ever heard.

Yeah. Kate really wanted to do it. And she was originally, I don't know if you know this or not, but she was originally set to play Meryl Streep's role in Kramer vs. Kramer. So she wanted to try to get a role in a serious movie. She lobbied for the part, and Danny Melnick had a great theory about why Kate would be important to the film, and that is because the subject being so possibly intimidating to audiences that if you had somebody like Kate Jackson, who was a TV star and had been in their living rooms every week, that that would be something subconsciously maybe that someone that they could connect through or guide them through this forbidden territory, if you will, who might ... you know ... that they could identify and relate to who might carry them through this dicey subject matter. And the theory being that at the end of the movie, she really comes around and accepts it and says this is how it has to be, and I just want to be happy, that the audience in relating to her throughout would come to the same conclusion at the end that she does. And that was a smart way to go, and I thought Kate was terrific. It was an easy shoot considering the subject matter. I've been on a lot tougher shoots with less nerve-racking subject matter, and everyone was really committed.

Which other actors did you pursue for the male roles?

Well, I know originally they had offered it to Harrison Ford, and he just wasn't going to do it. They had offered it to Richard Gere, if I recall. I know Michael Douglas was one actor who actually gave it some thought, serious consideration, and kind of went back and forth, and was very close to committing. Then his people talked him out of it. They were like, "Are you crazy? Kiss another man on the screen? Are you nuts?" That sort of thing. And finally, he backed out. And I think it was at that point, because he had kept us waiting for a long time, and at that point we said, look, just fuck it, let's just get the best actors we can. Let's move. And that's how that came about.

I think Harry was very well cast. He's magnetic on-screen.

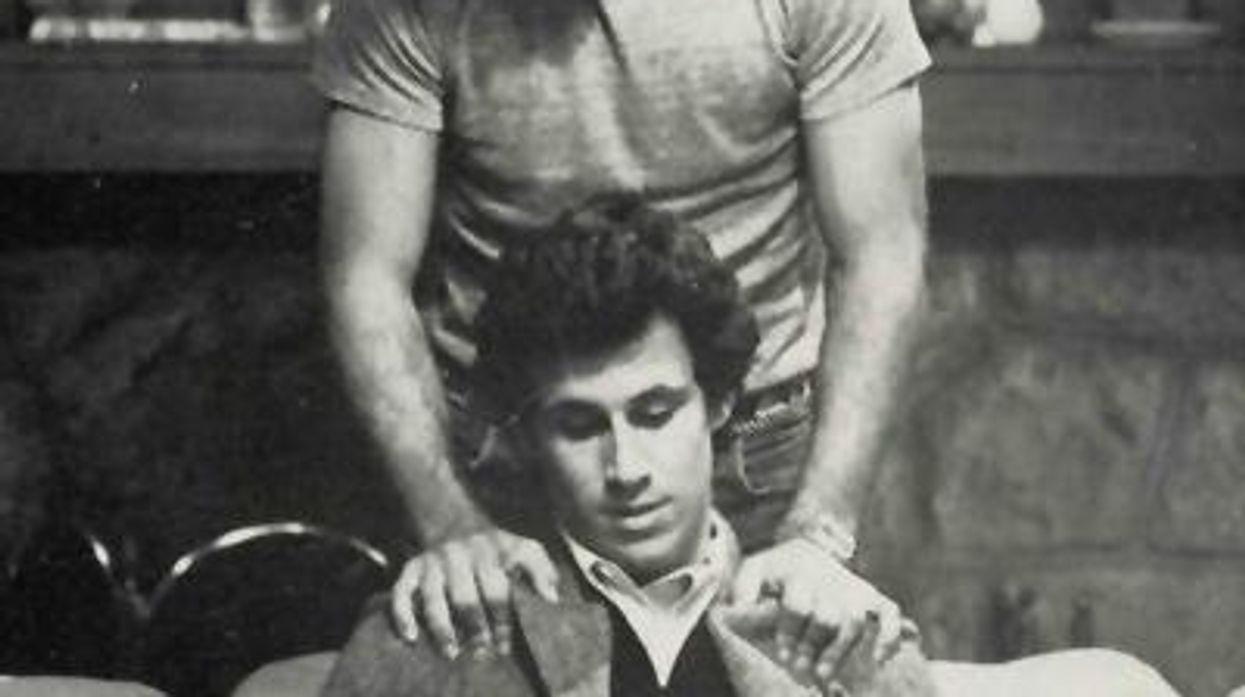

And by the way, those actors were asked to play the Michael Ontkean part. With Harry ... well, Harry wasn't exactly an unknown, because he had done Clash of the Titans, and he had done Studs Lonigan on TV and a couple of other movies. So he wasn't exactly an unknown, but certainly not a major star at the time. Harry was great. Both of those guys and Kate too. I mean, they were totally committed to making it as real and honest as possible. Harry wanted to know the whole scene, so I would take him out on a tour of West Hollywood bars. And really, he wanted to know how I would wear my watch, which is kind of funny. He was very great. He was great about it.

Did the guys in the bars recognize Harry?

Oh, yeah. Every gay man had seen Clash of the Titans. When they'd come up to him he'd use that old line, "I'm just here doing research." Michael, on the other hand, didn't want to go out and do research. He felt that character wouldn't have known the scene.

I imagine that after the furor over Cruising a couple of years earlier, gay people were anticipating a film like yours.

Oh, my God, there was a lot of anticipation, particularly in the gay community. Every newspaper and magazine from The Advocate to Frontiers and Blue Boy did articles on it. The script had gotten out, and word got out that it was a very positive portrayal. That was considered a breakthrough. People were rooting for it and were eager to see it.

What challenges did Fox face with marketing the film?

This was new territory. No one had explored this theme before, certainly not in a positive way, so the studio was nervous about how to sell it. They had two campaigns -- one for the straight community and another for the gay community. The campaign for the gay community was what it was, they already knew about it. For the straight community, they camouflaged it. They were concerned that people would accept it. They said it without saying it, like "Claire has been married to the same man for either years but suddenly something came between them." They did everything they could to not say it. I understood their concern. You have to look at where we were as a country then. The marketing was very tricky on this one.

This was written pretty much prior to the AIDS epidemic, but there's a scene in which Michael's character examines Harry that always makes me think it's going in a different direction.

Interesting. You're looking at it from the benefit of hindsight. I remember around late '81 or early'82 and the film had been finished at that point, this strange disease that was affecting people in New York. AIDS didn't really become widely known until late '82, and Making Love was released in February 1982. We were just not aware of it at the time. I can see looking back now that that scene has that eerie undercurrent.

You came out publicly in an interview with The Advocate around the time of the film's release.

Another thing I decided was that if I was going to write this movie, I would also have the responsibility of speaking for it and going public and saying that it comes from a point of truth. Once I made up my mind to do it. I made up my mind to say this film is very personal to me. I felt it was important to give the film credibility and legitimacy. I felt it was important at that time in changing people's perceptions of what a gay person was. In 1982 most people thought of a gay person as a queeny hairdresser or the butt of a joke. I felt that if I went on TV, and I was on the Today show and 20/20 and Fox sent me around the country to do talk shows, that if people just saw an average, ordinary person who said I'm gay and I'm happy and I'm proud to be who I am. I felt that if I could present myself as a gay man, people might say, "He's not so threatening, maybe he's not someone to be afraid of and condemn." I felt that was incumbent on me at that time because no one else was doing it and I had the movie to promote.

Did anyone try to convince you not to?

Some people asked if I was crazy and said no one would ever hire me. But that's the risk you take. I was never going to write a Bruce Willis action movie anyway. I just bit the bullet and did it. My career may have suffered in some quarters, but I was fine after that. I still got movies made after that and got hired for jobs. So looking back, I'm very glad I did it.

I got hundreds and hundreds of letters from young gay men all over the country, who said they had to sneak out of the house to see this movie or they had to drive 50 miles to the nearest town where it was playing. "This movie gave me a sense of pride and acceptance." "I was able to come out to my family or come out to my wife." "I realized I've been living a fraud." I received letters like that constantly. It's great as a screenwriter its gratifying to know you touched people that way. To this day I still have people who search me out and email me and tell they'd never seen it or watched it again and it made them feel really good about themselves. On the basis of that, I'd say the impact is very strong.

What do you think when you watch the film today?

Well, with any film I've made I cringe at certain places and think, How could they have left that scene in? I can't be objective. There are moments that really bother me, but there are also moments that are very affecting and I feel good about. I look at it from two perspectives: as a piece of filmmaking and as a piece of sociopolitical theater in terms of the statement it's making. For the most part I'm very happy with it.

How have you seen perceptions of LGBT people change since the film premiered?

When Brokeback Mountain came out a few years ago I got calls from journalists asking how gay images in film have changed over the years. I said I think public perception has changed enormously, mostly due to television. Everywhere you look there are gay characters on TV. Once people see gay characters in the comfort of their homes the more the concept of homosexuality is destigmatized. We've seen this in polls in acceptance of same-sex marriage. I think perceptions have really changed as they see we're just part of the fabric of society

Making Love will screen tonight at 6:30 p.m. at L.A.'s Harmony Gold Theatre with Sandler and Hamlin in attendance. For more information go to Outfest.org.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes