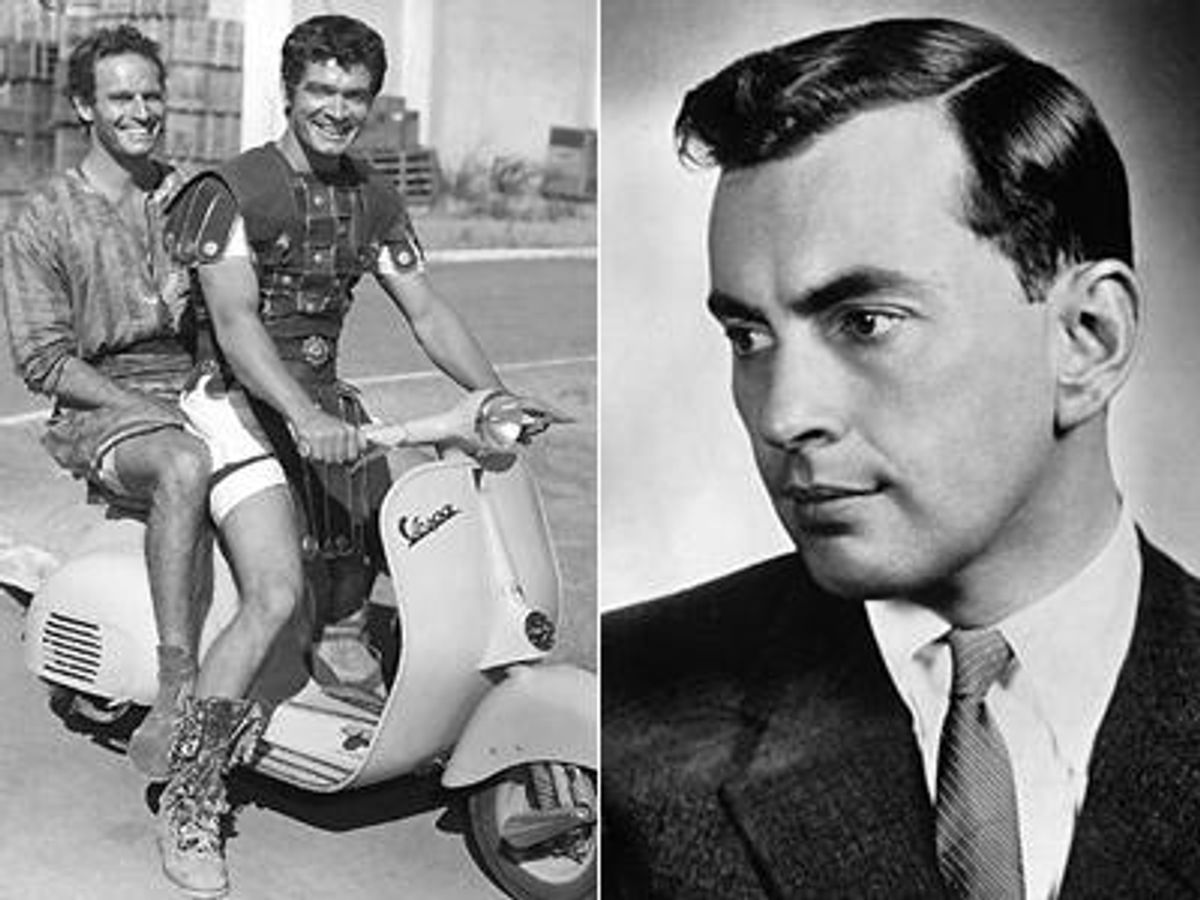

One of the most talked-about revelations from the documentary The Celluloid Closet was that Gore Vidal had infused a subtle yet clear gay subtext into the screeplay for the epic 1959 film Ben-Hur. However, when Charlton Heston, who played Judah Ben-Hur, heard Vidal's admission, it prompted the conservative celebrity to engage in a campaign to diminish Vidal's work on the film and to deny that subtext.

Vidal and Heston went back and forth in letters to the editor of Time, the Los Angeles Times, and The Advocate.The June 25, 1996, article can be found here, but we've also acquired the full typewritten and faxed letter, sent in May 1996. The letter, on the next page, has never been published in full. In true Vidal fashion, the saucy letter does not disappoint.

Watch the excerpt from The Celluloid Closet below and read the letter on the next page.

To: Anne Stockwell

From: G. Vidal

Date: May 9, 1996

I think we must all be charitable when it comes to Charleton Heston, whose career peaked with the film

Ben-Hur, kitsch which has, as kitsch will, become camp. Happily, he has other strings to his balsa-wood bow: spokesperson for the

National Review, and, as if that were not glory enough, proud trumpet for the National Rifle Association. Over the years I have told the funny story of how I wrote a love scene for Ben-Hur and Messala [played by Stephen Boyd] and how only the actor playing Messala was told what the scene was about because, according to director [William] Wyler, "Chuck will fall apart." In numerous accounts of his own marvelously dull life, Chuck has told us about his triumph as Ben-Hur. With each version, he adds, alas, new lies (proximity to

the

National Review's editor can put anyone's veracity at risk).

The facts:

Ben-Hur was the third picture in a row that I, as a contract writer at MGM, wrote for producer Sam Zimbalist (the others,

The Catered Affair, and

I Accuse). I arrived on the same plane with Zimbalist and Wyler not for a "trial run" but as the writer. Since I could only stay for a couple of months, Christopher Fry ... was on hand to replace me when my work was done.

Zimbalist died in the middle of the picture, and so the credits were totally confused and neither Fry nor I was credited with our work, which was the entire script of which the first two-thirds was mine. Now my weeks in Rome (described in

Palimpsest) becomes four days, according to Chuck. This is very bold. But then in my memoir, I did describe how no one at MGM wanted him for the film and only after [Paul] Newman and [Rock] Hudson were unavailable did Zimbalist, glumly, accept Heston. Over the years, his "obsession," to use his words, has gotten out of control. I always told Wyler (who didn't want to believe, later, what we had indeed done in the famous "love" scene) "Let's watch the film together. Watch what Boyd is doing." Wyler, a friend, would never watch with me. But the reviewers in the

N.Y. Times and the

L.A. Times [who reviewed]

The Celluloid Closet watched and saw very clearly what I had done, and said so, contradicting the gregarious Chuck. Incidentally, one of the producers of

The Celluloid Closet told me that they got a powerful message from homophobe Heston to the effect that a character he had also "acted" on the screen, Michelangelo, was in no way homosexual. But what is one to do with an old actor who, when he works, often wears two toupees, one on top of the other in the interest of verisimilitude? Long ago, in a play called

Design for a Stained Glass Window, he gazed upon ... yes, Dorothy and Toto and the Yellow Brick Road ... but now I grew as garrulous as he.