Thanks to a member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, a gay star of silent and early sound films is returning to the spotlight -- like a message in a bottle.

Stewart Copeland, the Police drummer turned prolific composer for film, television, theater, and concert halls, has written a new orchestral score to accompany the 1925 silent version of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, one of the most prestigious films of the era and the crowning achievement of its star, Ramon Novarro.

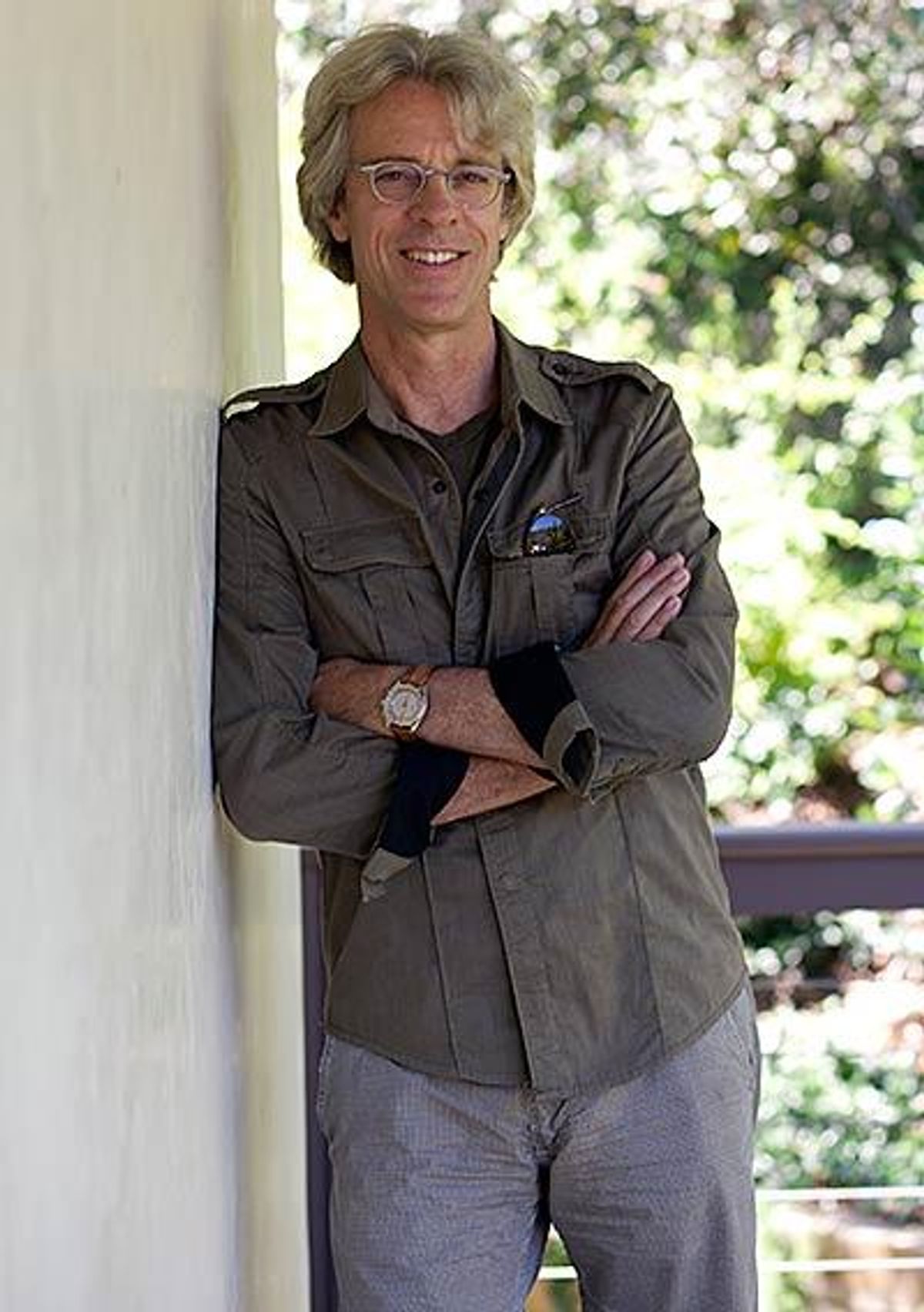

"When you look at it very closely, you see that every frame of it is a work of art," says Copeland, who oversaw a digital restoration of the film to go with his score. The restored movie and his music for it premiered last spring in Norfolk, Va., as part of the Virginia Arts Festival, and the next screening will be Tuesday in Chicago, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, joined by Copeland, performing the score.

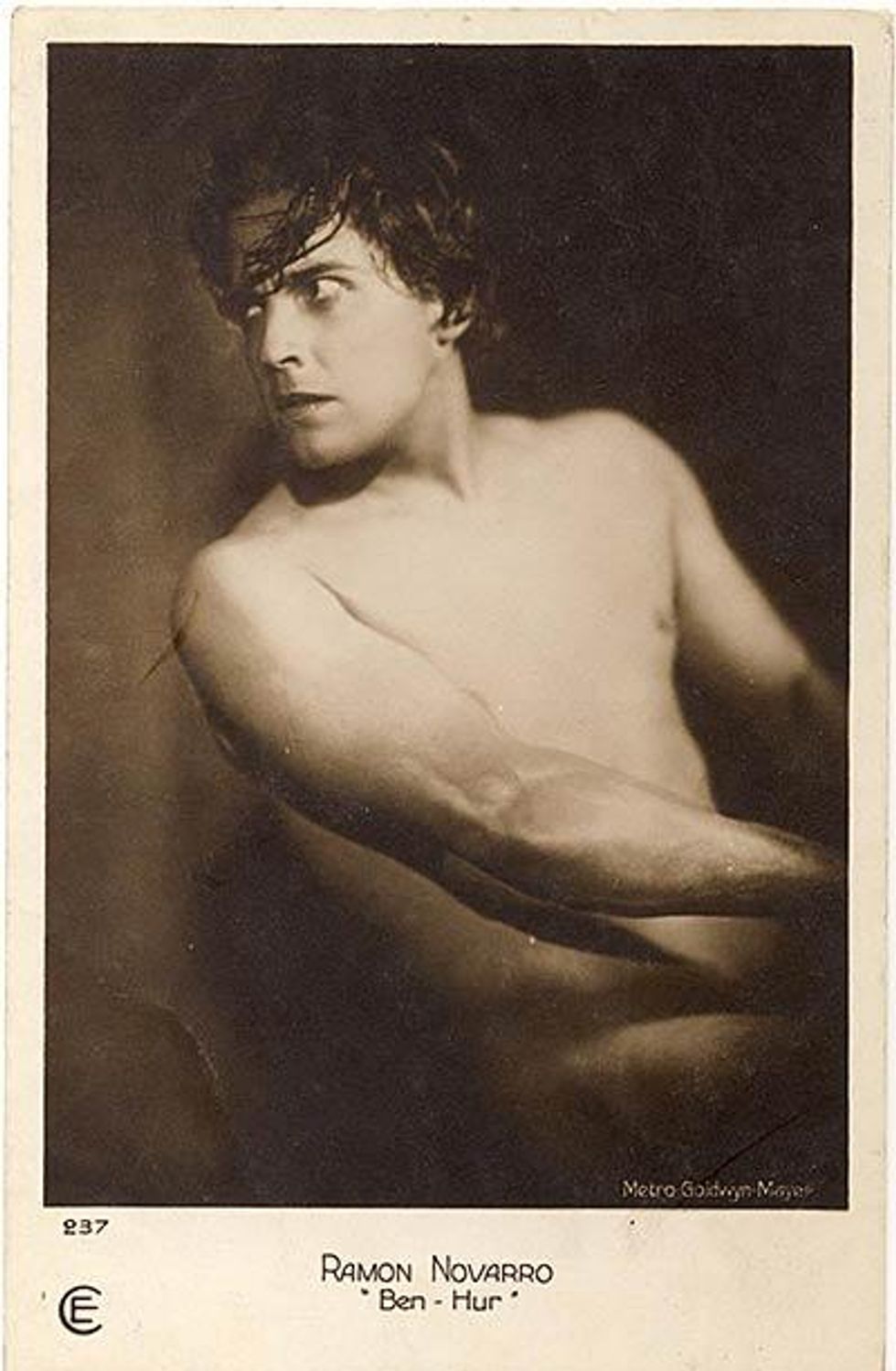

The privately gay Novarro is largely unknown today except to vintage-movie buffs and those familiar with the circumstances of his death -- he was murdered by a hustler in 1968. But he was a rival to Rudolph Valentino in the 1920s and remained a star into the '30s -- and Ben-Hur, directed by Fred Niblo, was undoubtedly the biggest film of his career.

Copeland wasn't a big fan of silent films or particularly familiar with either Novarro or Niblo -- "I've been working in talkies for decades," he cracks -- but when he saw the silent Ben-Hur at the suggestion of his manager, Derek Power, he was awestruck. "The first exposure to the great masterpiece of that era is like cutting straight to the Wagner," he says.

The film is based on the 1880 novel by former Civil War general Lew Wallace. Written by Wallace as a means to explain and defend Christian theology, it tells the story of Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish prince in the first century A.D. who is enslaved by the Romans after being wrongfully accused of a misdeed. He becomes a great athlete, seeks revenge on the friend who betrayed him (Messala, his rival in the climactic chariot race), and embraces Christianity. Wallace's melodramatic and sentimental work was the best-selling novel of the 19th century, and it has been frequently adapted for stage and screen. The 1959 movie version, directed by William Wyler and starring Charlton Heston, won a record 11 Academy Awards, and yet another film is in the works -- set to star Boardwalk Empire's Jack Huston -- with a 2016 release planned.

A few years ago, Copeland wrote the music for an epic stage production of Ben-Hur, which premiered in London in 2009 and has been performed extensively around Europe. He has adapted that score to accompany the silent film.

One of the most impressive things about the 1925 film, says Copeland, is that all the action is live, as no one had even imagined the special effects technology available to filmmakers today. "It really is happening -- it really is a cast of tens of thousands doing these things before your eyes," he says.

The film was a troubled production. It was originally to be shot on location in Italy, but most of that footage ended up scrapped, and when the production relocated to Los Angeles, director Charles J. Brabin was replaced by Niblo and star George Walsh by Novarro. It was the most expensive film of the silent era, coming in at $4 million, an amount that Novarro biographer Andre Soares estimates would be in nine figures today. With distribution and publicity costs on top of that, the film didn't recoup studio MGM's investment despite doing great box office, but it brought invaluable prestige to the studio, newly created from the merger of three companies.

Novarro made other hit films, before and after Ben-Hur. Scaramouche and The Pagan were among his silent standouts, and he made a successful transition to sound despite his Mexican accent -- studio executives at the time feared that foreign accents would be unpalatable to moviegoers. The handsome Novarro, born Ramon Samaniego in Durango, Mexico, in 1899, had a pleasant speaking voice (unlike some silent stars) and was also a talented singer who toyed with the idea of becoming an opera star. One of his biggest sound films was 1931's Mata Hari, with Greta Garbo playing a highly fictionalized version of the World War I spy.

By the mid-1930s, however, he was playing mostly supporting roles. Although he kept on working, even doing TV guest shots into the '60s, "never again was Novarro to appear in a motion picture nearly as monumental, as successful, or as highly acclaimed as Ben-Hur," writes Soares in the biography Beyond Paradise. Soares attributes the decline of Novarro's career not to homophobia but to "his own lack of professional focus" and a "lack of vision" on the part of MGM executives Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg. Besides having operatic ambitions, Novarro, a devout Catholic, considered entering a monastery. And Mayer and Thalberg often cast him in unsuitable roles in uninspired films.

Like most gay men of his time, Novarro was discreet about his sexuality -- studios occasionally planted rumors about supposed heterosexual romances, but usually explained his bachelor status by citing his devotion to his church and his parents, brothers, and sisters. But he hardly led a monastic existence. He had some long-term relationships, such as his 1920s liaison with Herbert Howe, a fan-magazine writer who also served as his publicist -- something not deemed a conflict of interest in that era. But in his later years, he frequently paid for sex.

In October 1968, Paul Ferguson, a sometimes hustler, and his brother Tom got Novarro's phone number from a friend and obtained an invitation to his home in L.A.'s Laurel Canyon. The brothers, who both had criminal records, showed up at Novarro's door the afternoon of October 30. His secretary, Edward Weber, found Novarro dead in his bed the next morning. He was bloody and had been beaten severely; a coroner's report found that he had choked to death on his own blood. Someone had scrawled "us girls are better than fagits" on a bedroom mirror.

Both brothers stood trial for first-degree murder, with Tom at one point claiming he struck Novarro in response to sexual advances. The 1969 trial was marked by homophobia on the part of the defense attorneys, with one saying, "Would this have happened if Novarro had not been a seducer and a traducer of young men?" In the end, both brothers were convicted and sentenced to life in prison, but Tom Ferguson was paroled in 1977, Paul in 1978. Tom committed suicide in 2005. Paul, now imprisoned in Missouri for rape, has said he, not Tom, was the perpetrator. (See Out magazine's extensive article here.)

There have been many sensational but apocryphal tales about the murder, Soares writes, adding that Novarro deserves to be remembered not as a murder victim but as a "complex individual" and an "accomplished -- and historically important -- actor."

The new life that Stewart Copeland is breathing into Ben-Hur may help. He hopes to book additional screenings of the film with his score's accompaniment; there is one scheduled for Paris in 2016.

The straight musician, who considers himself an ally of LGBT people ("my heart and love are with them -- we are all one"), is working on a variety of other projects as well, including his fifth effort for California's Long Beach Opera, this one based on the science fiction novel The Invention of Morel. As for another Police reunion, he says, "No how, no way -- but we always say that."

He also hopes that as Ben-Hur inspired him, silent cinema will inspire other composers. "Hopefully more composers will dive into this treasure trove of silent films," he says.

Ben-Hur will screen, accompanied by the Chicago Symphony playing Copeland's score, at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday at Symphony Center. Get tickets and more information here, and watch a preview below. For more about Copeland, visit StewartCopeland.net. Andre Soares's Beyond Paradise is available through Amazon.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered