All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Sabbath quiet--no electricity, car, phone, or computer. In the afternoon after the troops return from the synagogue, after a four-course meal, out-of-tune singing, and Levi's ponderous lessons, the guests leave and Shalom goes down for his nap. Itzik, Sarah, Avrami, and Mendel spread books and toys through the den and playroom and get busy with their plans. I vaguely supervise from the old orange recliner, tired, leaning back. With the backdrop of bookshelves behind me, I feel a restless nostalgia for our old texts. I take a Hebrew and English Bible and turn to Genesis. I begin to read, but I've been learning to read critically and it seems I can't turn off that critical eye. It's as if a scrim of holiness that once softened and justified every biblical message has been pulled away. But the commentaries are the voice of the sages. They say who we are.

Remembered lines surge from the pages. I page through, alarmed. I pause over the comment that charges Eve with responsibility for the great sin that taints mankind, then turn quickly to the place where they criticize Sarah for laughing at God's blessing (but maybe it was joy!), denounce Leah for desiring her husband, blame Dinah for her own rape. I pull out Exodus, and page over where commentaries insist Miriam was punished with leprosy for speaking her mind. Do not speak overly with women, our sages say. Women are a source of inane prattle. Women steal a man's time from Torah study.

Trending stories

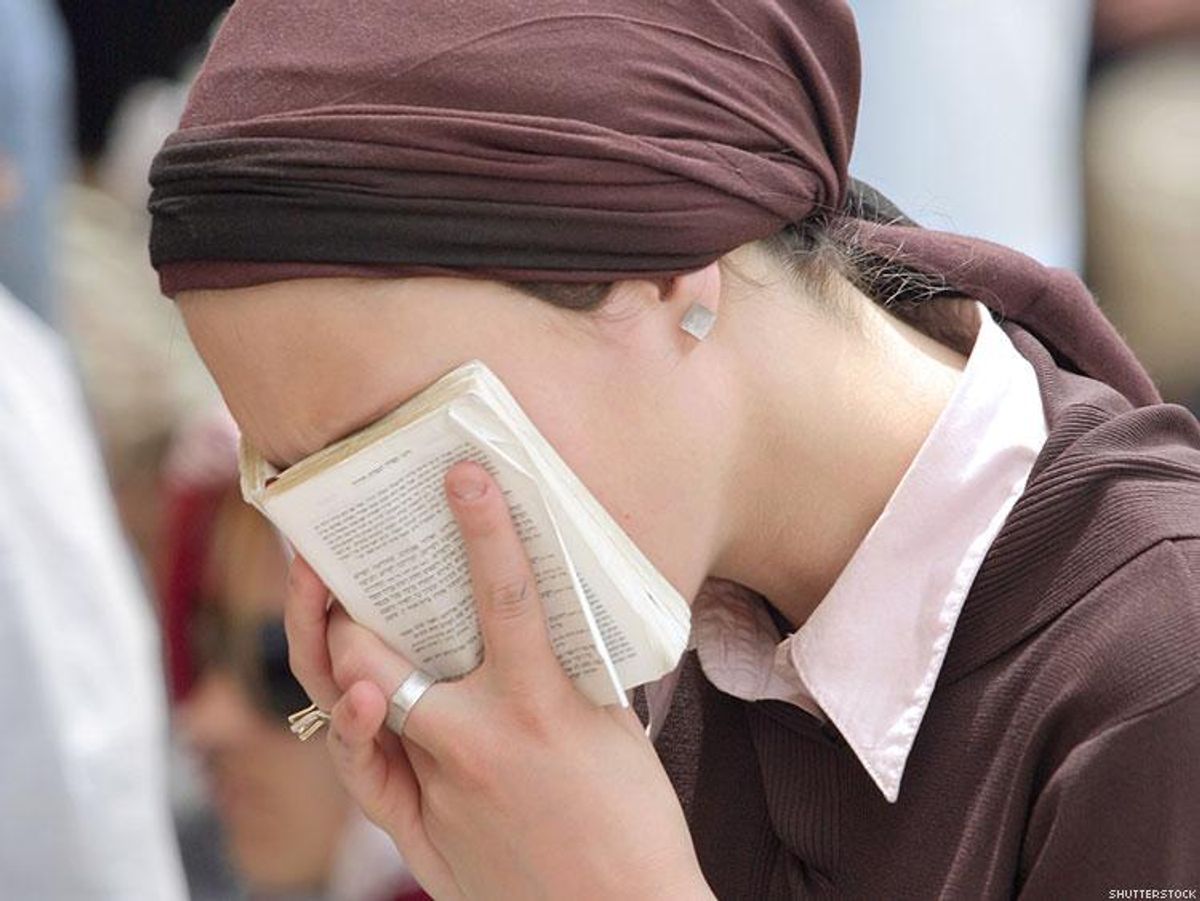

I sit up. If their image of Sarah and their Leah and even their Dinah are our role models, and they are, if what the rabbis say about our Foremothers is holy and true, then we women should cover ourselves. That legacy makes us want to hide ourselves, as if, by obeying the rabbis' injunctions and covering our shamed bodies, we redeem ourselves from Eve's sin, Sarah's laugh, Leah's desire, Dinah's beauty, Miriam's mind. As if, in a world that holds this book as the story of who we are, womankind needs redemption.

I look down at my long skirt and stockings and tuck a wisp of hair back into my scarf. Then I shake my head. I can't do it. I can't humbly engage in study any more. I can't go back.

So I launch out of my seat, kids still playing, head to my bedroom, and return in no time with the first secular book I've ever bought as an adult, by Adrienne Rich--a compendium of her writing. I was out shopping across town the other day and ducked into a bookstore, where I found people browsing without reservation, without censors. So I browsed, too, as if such freedom were nothing, and picked up a book with this vaguely familiar name. This will be my Sabbath reading.

Itzik climbs into the recliner with me and puts his head in my lap. He was up late at the Sabbath table and still needs his naps. Hoping he'll doze, I sit very still and stroke his shoulder. Sleepy-eyed, I turn pages, scanning new territory, until the poetry begins to seep into a half-conscious place like the slow, deep spread of spilled ink.

The rules break like a thermometer,

Quicksilver spills across the charted systems;

Avrami and Sarah haul in wooden blocks from the playroom.

A woman's voice singing old songs... plucked and fingered by women outside the law.

Is that what I'm doing? Singing old songs, even as women outside the Law pull me away from the rules?

The pile of blocks on the floor has grown. Avrami gets up to go get more. I point at the mound, my steady gaze on him. "You can bring them if you clean them," I say. Itzik shifts on my lap and sighs. I read.

This is the law of volcanoes

making them eternally and visibly female.

No height without depth, without a burning core

Something is waking me up, as if I've been cold and dead a long time.

Libby comes in the front door with a friend. The two go off to her room.

I read on. There is a lot I don't understand. But, I think, I can take years over this if I want. This book is mine. I turn the page.

your body

will haunt mine--tender, delicate

your lovemaking.

I sit up then. Tender, delicate--I think she must be writing to a woman. I decide she's writing about a woman. In my life, I have never heard anyone speak this picture openly. I grip the page. My face flushes.

Mendel dumps the bucket of Legos out on the carpet. The room is covered with toys, the playroom empty, children at my feet. "Clean up the blocks before you touch those Legos," I say.

"No, Mommy!" Mendel says. "We're doing something. We'll clean up later. Promise!" Avrami and Sarah are nodding. Itzik is asleep in my lap.

Your traveled, generous thighs

between which my whole face has come and come--

the innocence and wisdom of the place my tongue has found

there--

Levi walks in, his face puffy from his Sabbath nap. He goes into the kitchen to get a cup of coffee.

Your strong tongue and slender fingers

reaching where I had been waiting years for you

in my rose-wet cave--

I slam the book closed. Shut my eyes. Take a breath. Let out a breath. Take a breath. Forget to let it out. Sarah glances up, a second's notice, then away.

Face hot, I stand with the closed book and lift sleeping Itzik, settling his head on my shoulder. I keep my expression impassive as I glide to his room to lower him into his bed. The last words of the poem stay with me as I move down the hall:

Whatever happens, this is.