If gay people are part of the human experience, then why are mainstream publishers and straight readers so quick to keep gay characters in the closet?

May 16 2013 4:19 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

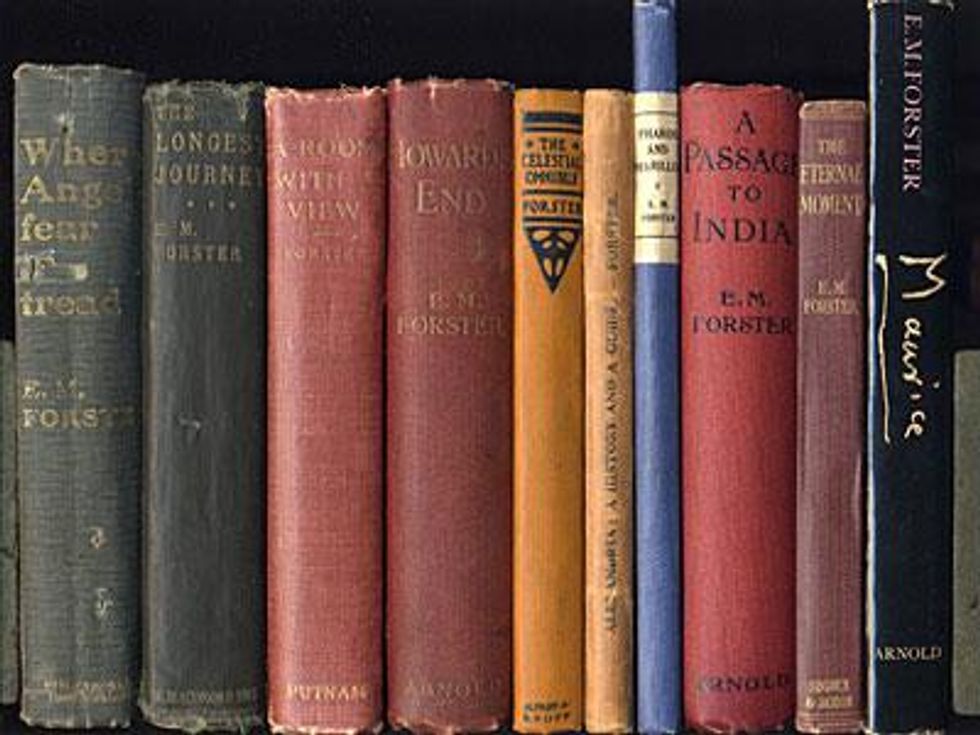

Gay writers have been passing for centuries. From Shakespeare's sonnets -- now widely believed to be addressed to a man -- to the deceptively simple romances of E.M. Forster, an author's personal experience of desire has often been morphed on the page in order to turn homosexual reality into heterosexual fiction.

I venture to say that the phenomenon continues in these supposedly more enlightened days, if only for mercenary reasons: Write a book about straight people and you increase your chances of publication and sales. (If you want to be daring, throw in a gay character or two, but only as the hero's sidekick.) Write one about gay people and count the number of doors slammed in your face.

I learned that lesson the hard way. My first novel, Chemistry, whose main characters are all gay, was rejected by more than 50 agents. While each agent believed the book had merit, their most common excuse for turning it down was that they lacked the "passion" for the subject needed to sell something in today's tight marketplace. Eventually I gave up on the agent path and started going directly to publishers on my own. When I approached Haworth Press, which at the time specialized in gay fiction, I received a contract on the basis of 50 pages.

I can't exactly blame the literary establishment. Publishing is a business, after all. The hesitation to publish gay-themed books is based on the assumption that the majority of straight readers won't be interested. While gay people have been reading about them for years, with little complaint, straight people are evidently less willing to return the favor.

The irony is that even my savior, Haworth, surrendered to market pressure a year or so later, when they canceled the imprint under which they had published Chemistry -- not because it was gay, but because it was fiction. In a culture obsessed with "reality" TV and memoir, the market for works that dare to admit they're made up grows ever smaller. But that's another, much sadder topic, suitable for an entirely different essay. For now, suffice it to say that I was fortunate to have Chemistry picked up by Lethe Press, which this year also published my second novel, The Heart's History. (And yes, that one's about gay people too.)

Several years ago, when my first short story was published, my late father couldn't make it beyond the first paragraph. Dad just couldn't get past the opening image of two men in bed, so he never even reached the heart of the story. And neither, he implied, would anyone else who hadn't already lived that scene for himself.

After my father's awkward reaction to that first story, I put my writing into the closet, at least as far as my family was concerned. I kept writing, and I kept writing on gay subjects -- because that's what I know, that's my truth -- but I never shared it with them. And on those rare occasions when I managed to get something published, I didn't tell them. They knew I was gay, and they knew I was a writer -- but because I lived 3,000 miles away and because nothing I wrote ever found its way into a publication they were likely to read, my parents were quite safe from having to face either of those facts.

Skip forward a bit: same situation, different set of characters. When my second story was accepted by a magazine -- a gay magazine -- my boyfriend at the time came over with a bottle of champagne to celebrate. After toasting my success, he sat back and, still smiling, ventured a suggestion. "Why don't you write a story," he said, pausing with an odd mix of anxiety and suspense, "for the mainstream?"

My political hackles were immediately raised. Was this a conspiracy? Had my parents gotten to him? What was the mainstream, anyway, and what did it have to do with literature? Was I supposed to write for some idealized middle America -- a husband and wife with 2.4 children and a white picket fence? What's wrong with putting my real life on the page? Nobody tells Toni Morrison to write about white people.

But I knew what he meant. He was thinking about my career. If I were to make it as a writer, he thought, I'd need to appeal to a larger audience -- that elusive "mainstream." And at least in his worldview, the mainstream doesn't want to read about us marginalized types -- me and Toni Morrison. The mainstream wants to read about ... the mainstream.

My boyfriend's advice was the artistic version of the cliche that every parent seems to use when you come out of the closet: "I accept you, dear; I just worry about the reaction of other people."

In Tom's ever-so-practical opinion, the solution to my career woes was to write about straight people. After all, he suggested, homosexuality was really just a backdrop for my work; it wasn't the overriding theme. If my themes were universal, couldn't I explore them through stories about heterosexuals? Why risk antagonizing 90% of the population and thereby immediately reduce my potential readership? There goes all hope of the New York Times best-seller list, not to mention a window display at Barnes & Noble.

E.M. Forster crossed the bridge from mainstream novelist to gay author, post-mortem.

E.M. Forster crossed the bridge from mainstream novelist to gay author, post-mortem.I listened politely and smiled in all the right places, like Sammy Davis Jr. being complimented on his tap dancing by Archie Bunker. But I couldn't help thinking that all this righteous concern for my career reeked of a literary "don't ask, don't tell." It was other people's sensibilities I was being advised to watch out for: There was nothing wrong with being gay, only talking about it. Suddenly, the reading public had turned into a crew of sailors on a submarine, terrified of dropping the soap.

My brother had to Google me to find out that I was publishing a novel. And when he asked about it, when he sincerely congratulated me on accomplishing the goal he knew I'd had for most of my life, I felt a new kind of shame. It wasn't the kind that drives you into the closet, but rather shame for having let the closet win, letting it come between you and your loved ones. (I keep hearing the mother in Torch Song Trilogy so painfully and astutely wailing, "You shut me out of your life and then blame me for not being there!")

The truth is that as soon as the manuscript went into production I became a bit terrified of the exposure it would bring. Now, I thought, everyone--family, coworkers, my dentist -- would know my deepest thoughts and darkest feelings. What was I thinking? My therapist had to remind me that the word publish literally means "to make public": What I'd been craving my entire life was exactly what I was now most afraid of. Careful what you wish for.

The closet is a very narrow place. People put us in there by focusing on one aspect of our lives -- reducing our human complexity to the single thing that makes them uncomfortable. And we stay there only by internalizing that narrow view. When we closet ourselves, we are in effect reducing ourselves -- seeing ourselves through someone else's myopic vision.

Chemistry is about a lot of things -- love and friendship, illness and cure, the ties that bind people together and the forces that tear them apart. It's about psychological damage and painfully liberating self-discovery. But all I feared anyone -- not least of all, my family -- would notice is that it's also about sex.

In this paranoid state of tunnel vision, I couldn't even hide behind the mask of fiction. That, I believed, could take me only so far: When my narrator, Neal, plays his cello -- an instrument I've never touched -- everyone who knew me would see that as fiction. But when he goes to bed with his lover, those familiar readers whose approval I craved would see only me.

My mother proved the point right away. An unsophisticated reader, she was from the beginning confused by the use of the first person in the book. When we spoke right after she'd finished the opening chapter, she repeatedly referred to the narrator as "you." If she already pictured me on every page, I wondered, what would she think when she reached the sex scenes?

The inevitable question, of course, is, What if it were heterosexual sex that I'd depicted in my work? How would she feel then, and how would I feel as I imagined her reading it? My mother and I have watched Fatal Attraction together more times than I care to admit -- to the point that its once-shocking sex scenes now seem as matter-of-fact as the opening credits. I could have written scenes like those. I've slept with women, and I've read my share of Sidney Sheldon (a very small share, for many reasons, was more than enough). I could have changed Zach to Zelda and had a very similar story to tell.

But it would be a story missing the key ingredient: truth.

At left: Lewis DeSimone

At left: Lewis DeSimoneIf a novel isn't truthful, it's nothing. And part of my truth is my sexuality. I happen to believe that sex -- as the most primal of urges, perhaps the only occasion when we are able to be fully present with another person, free of the mind's constant harping -- is one of humanity's greatest vehicles for truth. So Chemistry is full of sex. It's one of the ways I chart the narrator's path toward self-discovery and liberation. So what if my readers see me when they read the sex scenes? Why should my sex life be the occasion of shame? I came to see the publication of the novel as my opportunity to stop accepting the closet's revolving door and instead tear the damn thing off its hinges once and for all.

When it came time to work on my next book, questions about the role of gay life within the larger culture loomed large in my mind. The Heart's History is a love story and an elegy of sorts, but is also an examination of where we currently are as a community, and where we want to go next. When two of the characters, Greg and Victor, get legally married, their friends argue over whether it would be nobler to question mainstream values than to embrace them. It's a question that runs throughout the book -- the cost of assimilation, whether a loss of distinctive identity is a prerequisite for fitting in.

"Differences," my first lover told me long ago, "are gifts." He said this to reach across some chasm that divided us, some issue we were unable to come to terms on. But the line has stayed with me, resonating in ways I couldn't see then. It's no coincidence that so many artists are social outsiders: It's their separation from the mainstream that allows them to see it from such interesting angles. It's that sense of distance that gives their work meaning. The gift of difference is its ability to transcend itself, to enlighten the people on either side of the chasm -- to help them, together, form a bridge.

Our new politically correct society seems intrinsically schizophrenic to me. On the one hand, we're expected to recognize and respect cultural differences; on the other, we're supposed to downplay them to the point of meaninglessness. Personally, I've never put much stock in the notion that homosexuals are just like everyone else except for what we do in bed. But neither do I believe that I have to pierce my eyebrow and wear gold lame in order to be truly "queer." Either position asks us to conform -- if not to a straight ideal, then to a gay one. The point is that binary oppositions just don't work when it comes to something as complex as human character. We're all different in more ways than we know. Ultimately, even heterosexuals are as queer as a three-dollar bill.

In the end, any work of art worth its salt is a little subversive. A novel that depicts ordinary people doing ordinary things -- without irony, without tension -- will most often fall flat, or veer into the territory of melodrama. As Whitman pointed out long ago, "the particular is the only universal": It is only by looking at a specific situation, a specific life -- with all of its odd, quirky aspects -- that the reader can engage enough to discover a fundamental, universal truth. Generalizations are little more than platitudes; hard truth is to be found in the details of individual lives. And speaking of platitudes, isn't the oldest one in literature "Write what you know"?

What I know -- what all writers like to think they know -- is the human heart. And that is what we write about: gay, straight, male, female, black, white, young, old -- we all write about the universal truths of the human heart. I use primarily gay characters to reveal those truths because they're the ones who come most naturally to my keyboard. Some characters occasionally come to me in female bodies or in heterosexual couplings, and I listen just as closely to them.

Ultimately I do write for the mainstream -- not to cater to their prejudices, but to share new ideas, new ways of seeing the world. Discerning readers learn more when their imagination is challenged, when they're confronted with things they've never seen -- a whaling ship in 19th-century New England, a man waking up to discover himself a cockroach, or two men locked in a loving embrace.

I wonder sometimes if the mainstream isn't just another myth, like the Easter Bunny or the melting pot. It's not a single current, but the churning of innumerable waves that keeps the water alive. I write in the hope that my work can float on those diverse waves, like a message in a bottle, and perhaps find its way to the far shore, to give its inhabitants a glimpse of life on the other side.

LEWIS DeSIMONE is a writer living in San Francisco. LewisDeSimone.com