Voices

Op-ed: The Stories That Gender-Nonconforming Kids Need

Op-ed: The Stories That Gender-Nonconforming Kids Need

Children's literature is too often a tale of two genders.

Cameron Keady

February 18 2014 6:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Op-ed: The Stories That Gender-Nonconforming Kids Need

What I remember most about being a kid is how small the world felt. Each day was predictably linear: wake up, go to school, come home, do homework, read in bed, go to sleep.

As adults we still follow a daily schedule that is also often predictable and structured, but the difference now is we have outlets -- outlets we create for ourselves that provide a release from the confines of routine, that let us relax and imagine and daydream for a while.

As a gender-nonconforming kid, these moments were more about escape than they were release. They were times of solitude I spent only with a picture book or building blocks, to grow my world just a little bit. It's not that my reality was dark and unhappy. I just couldn't find my place in it.

My struggle with gender identity became increasingly difficult when I couldn't even feel a sense of belonging in books, an outlet that brought me to a fictional world. These stories and fairytales provided an escape to fantastical places where animals could talk and treasure actually was buried under the letter "X," but when the story gave any semblance of reality, I felt isolated and shut out.

Too quickly kids are placed on either a blue or a pink path. And they are expected to follow it. Children who stray from this binary are often seen as lost, confused, or in some sort of phase. But that isn't the case. They are "both" and "neither," and they need resources to confirm that is OK. They need stories that look, sound, and feel like them. Parents of queer and gender-nonconforming children have resources, like gender therapists, pediatricians, and guidebooks to help understand and foster a child's gender development, but the child is often left to their own devices. In many cases, the only place a child has full agency to explore and educate themself is in a library.

What gender-nonconforming children need are media, particularly books, in which they can see themselves.

Lori Duron is the author of Raising My Rainbow: Adventures in Raising A Fabulous, Gender-Creative Son, and proud mother of C.J., a gender-nonconforming 7-year-old. C.J. has identified as gender-nonconforming since age 4. One of his favorite books is My Princess Boy, by Cheryl Kilodavis. Like C.J., the story's protagonist is a boy who likes pink and wears dresses. This book shows C.J. another boy like him, and this reflection of self encourages him to celebrate and take pride in his own identity. Though in many ways this story mirrors C.J.'s gender expression, it may not draw the same parallels for another boy that also identifies as nonconforming.

"[When we] read My Princess Boy, I am showing [C.J.] kids like himself, but I am not showing him other types of kids," says Duron. Just as she wants cisgender children to accept C.J., she wants him to understand and accept their gender expression, too.

For this broader understanding, Todd Parr is a favorite in the Duron household. His book, It's Okay to be Different illustrates cultural, physical, and emotional differences, while teaching readers to celebrate individuality. Its outreaching and relatable message of acceptance is inclusive and warm, and shows kids that identity is something complex that should be explored, not confined to a singular definition.

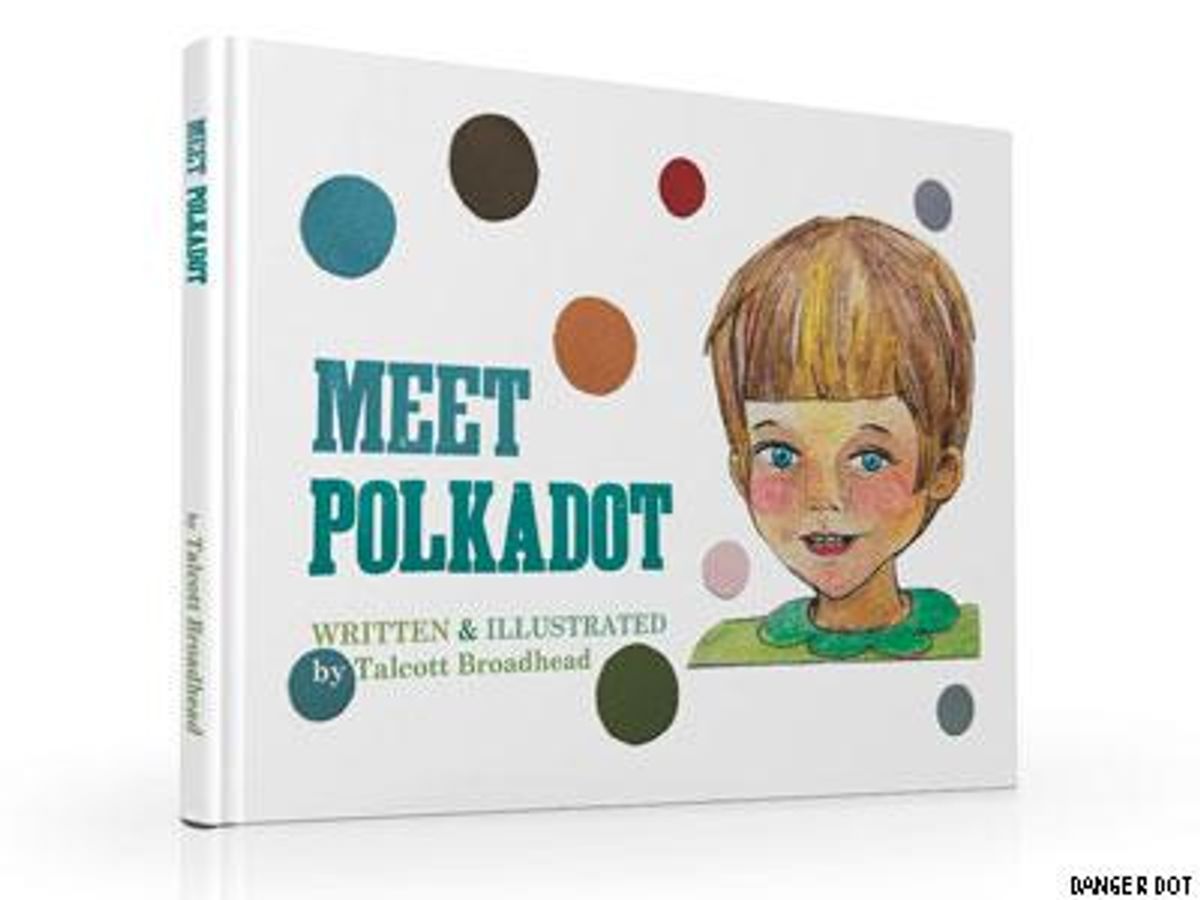

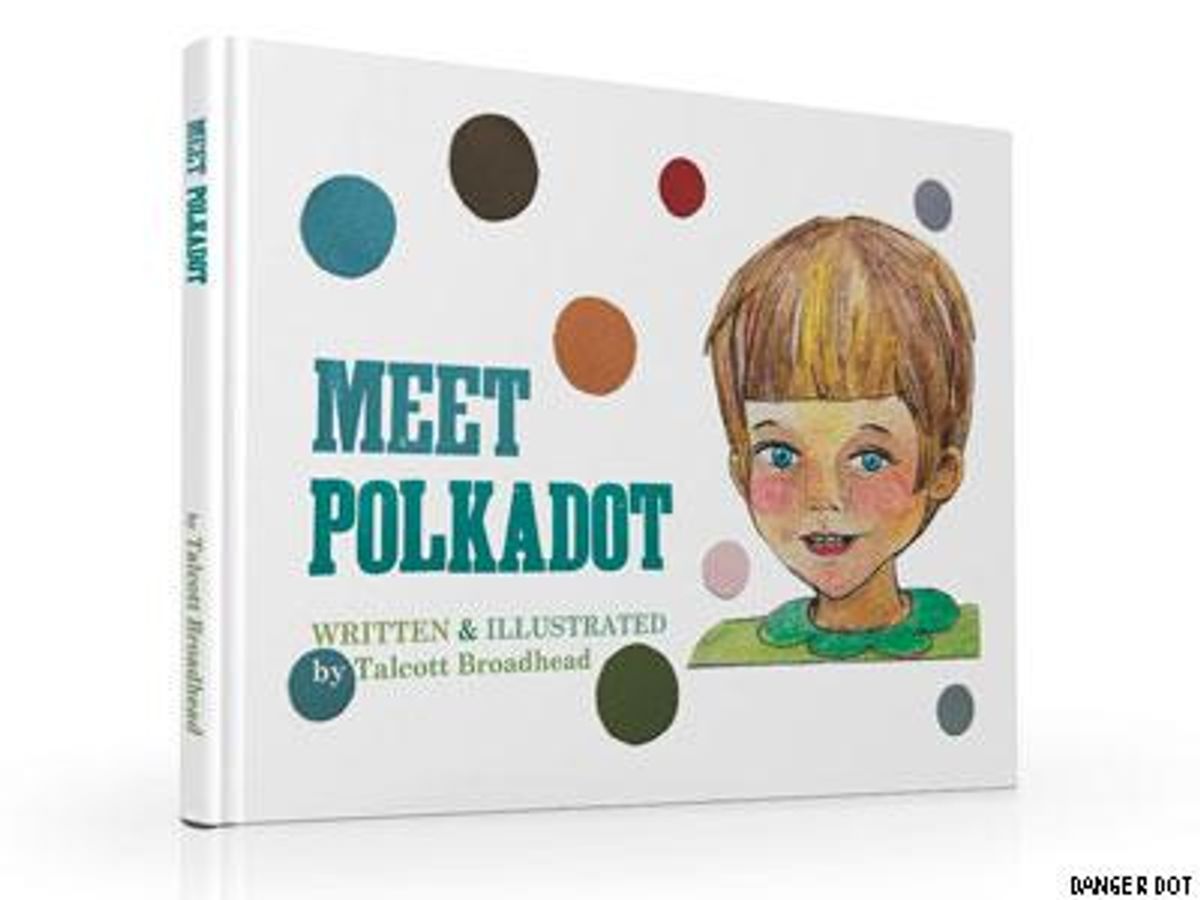

Author Talcott Broadhead explores this complexity in the children's book series, "Meet Polkadot." The main character is named Polkadot, a non-binary, trans kid. The books grow with Polkadot to reflect how each milestone of childhood is informed by the social construct of gender. The story is not just about Polkadot's identity, but about how it relates to the world around Polkadot.

This young character is taking our hand and leading us in the direction we need children's literature to move. But the reality is, adults take the lead. Even for a family like the Durons, who foster and encourage their child's nonconforming gender expression, these books are often distributed by small publishers and are difficult to find. Schools and public libraries are often resistant to add them to their shelves, deeming their subject matter inappropriate for a classroom. But it is the child who does not have love and support at home that needs these resources in school the most.

Children's books are meant to provoke a sense of wonder about the world. They should inspire and enhance reality, not just provide an escape from it. Books that include themes about nonconforming gender expression have the potential to be radical tools for social change. They allow for complex themes delivered simply, that allow a child's small world to grow and expand.

If children's literature continues to exclude this population that desperately needs them, the book industry is failing to complete its mission. We need books for gender-nonconforming children that present a spirit of optimism and rejection of impossibility. Granting children a confidence and self-assuredness early in life, through these stories and books, would make for much happier tales of growing up as gender-nonconforming.

Kids are smart, and often pragmatic, and logical. They know they can't be elves and wizards like in the books they read. But they should know they are still capable of magic.

CAMERON KEADY is an assistant editor at Time For Kids, a freelance news and culture writer for Refinery29, and a contributing editor for Gayletter.com.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella