My father was a bigot and an alcoholic.

He suspected that I was gay and hated me. When I was 10, I finally stood up to his virulence and violence, so he punched me and demanded that I get out of his house. These violent conflicts had become more frequent, but this time I knew I had to leave because I feared for my young life. I never went back.

Decades later, my mother called to tell me what would normally be considered upsetting news, but I was relieved. "Your father has lung cancer and secondary bone cancer. He doesn't have long to live." I couldn't help but think God had finally answered my prayers. But something inside wouldn't allow me to celebrate what would have at one time been good news. I pulled my thoughts together and surfaced from the darkness to which I was so accustomed as a child.

We were a middle-class family from a small suburban community just north of Seattle. My parents provided clothing, meals, and all of the incidentals required for raising a child. We looked good on the outside -- but the inside was unbearable for a gay child who just wanted to be loved.

I went into state custody and began my journey in the foster care system, and not long after, I landed on the streets of downtown Seattle, where I found a community of other children who were like me. I learned how to perform minor crimes, required as a means of survival, and began my career as a juvenile delinquent. I spent 11 years homeless on the streets, at one time more than half of my life. As a teenager, I became addicted to drugs and lost all hope for a normal, productive life. I wanted to die and attempted suicide.

Miraculously, at 21, a judge presented an opportunity for rehabilitation. I was tired of the life I never wanted to live in the first place, and so I changed everything. I haven't done it perfectly, but I haven't looked back.

My father and I never formally made amends, but after two family tragedies -- the deaths of both of my brothers -- we learned to tolerate each other for the sake of my fragile mother. I never wanted or needed "tolerance." I wanted to be celebrated for the perfect way that God created me. I wanted a father and I needed him to love me and to raise me into the strong man that he never believed me to be. I wanted empowering lectures and informative life lessons and someone to rely on when life threw me curveballs. Almost 40 years, and I could not remember one kind word or loving action from him.

I couldn't support him, but I had to support my mom, because she had been through enough and needed her only surviving son. But then as I processed this scenario, which was rated R for Real Life, everything that I had learned from my friends and supporters began to kick in. He wasn't present for me because he didn't know how to be. He had severe problems and couldn't even take care of himself -- let alone three kids and a wife.

The epiphany: I didn't want to be anything like him, but for me to be the kind man I wanted to be, I had to do the unimaginable -- I had to forgive him. Not just in theory but in action.

Radical reconciliation.

At the moment I came to this realization, I also decided I would do what I could to help as he neared the end of his life. Just with this thought, my heart began to lift from the darkness. I became resolved to do whatever I could to help him and my mother get through the final moments of his life and their 45-year marriage. I did this because I needed to be free and I wanted to give him the gift of unconditional and perfect love that he was so unable to give his gay son.

I flew from my home in Los Angeles to Seattle every weekend as his health slowly deteriorated. We didn't speak much, but I would feed him his pills and he would give me an occasional suspicious glance. But as time progressed, he began to realize my sincerity, and although we never had a "moment," toward the end I noticed him staring at me and not looking away. I placed my hand on his and his eyes began to smile, followed by his face. It was in that moment with my father that everything bad went away. Our relationship was healed as we both accepted and internalized mutual, spiritual forgiveness.

It's been several years since my dad passed away, but every Father's Day I remember this defining moment in my life that helps build me into the man I want to be, rather than the man I was being conditioned to be by a failed criminal and social justice system. I am recovered now and wrote a book about this and other experiences, which also celebrates the many children who did not have my kind of happy ending. I share my story with other at-risk and homeless children and nonprofits who serve this community to inspire a world free of bigotry and youth homelessness.

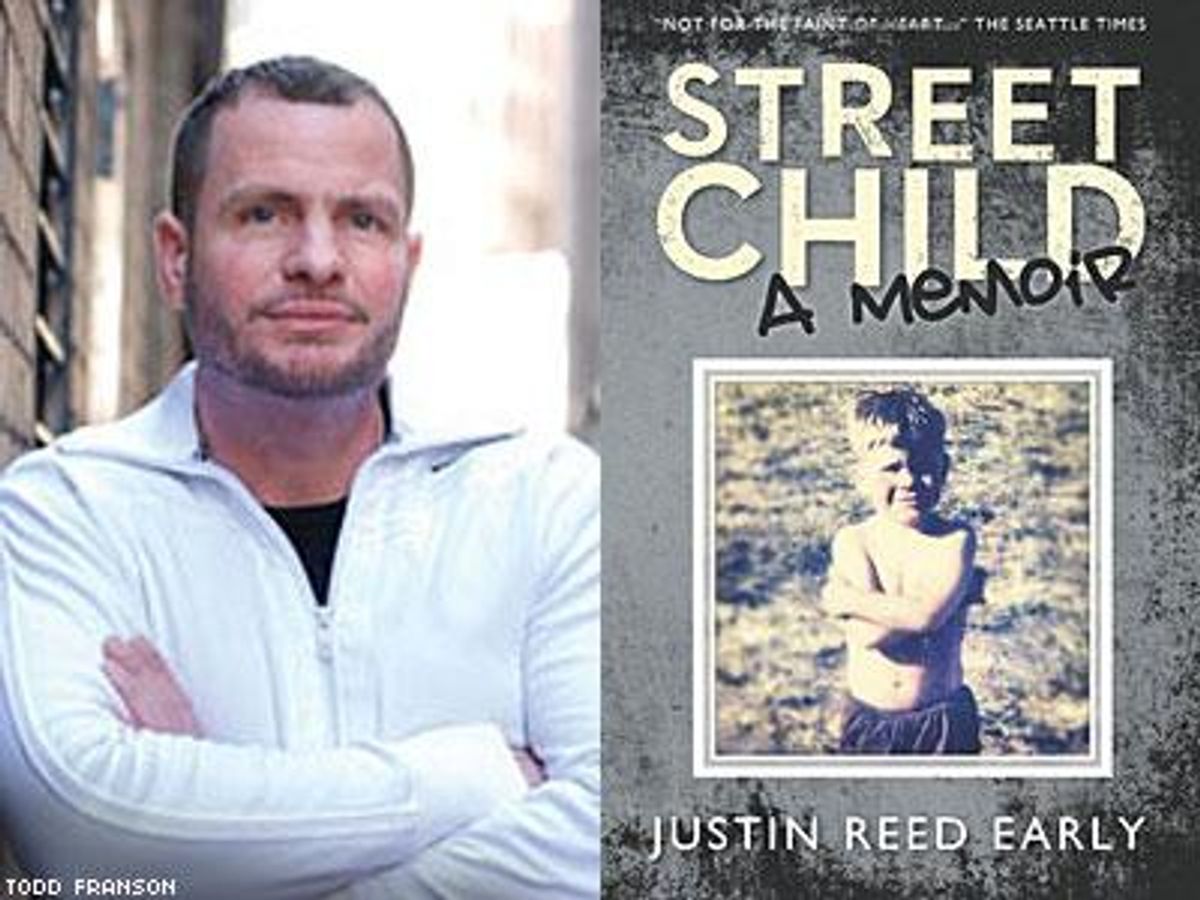

Justin Reed Early is the author of Street Child: A Memoir, which chronicles his and other children's real-life experiences on the streets of Seattle. He provides books at no cost to at-risk and homeless children in crisis.