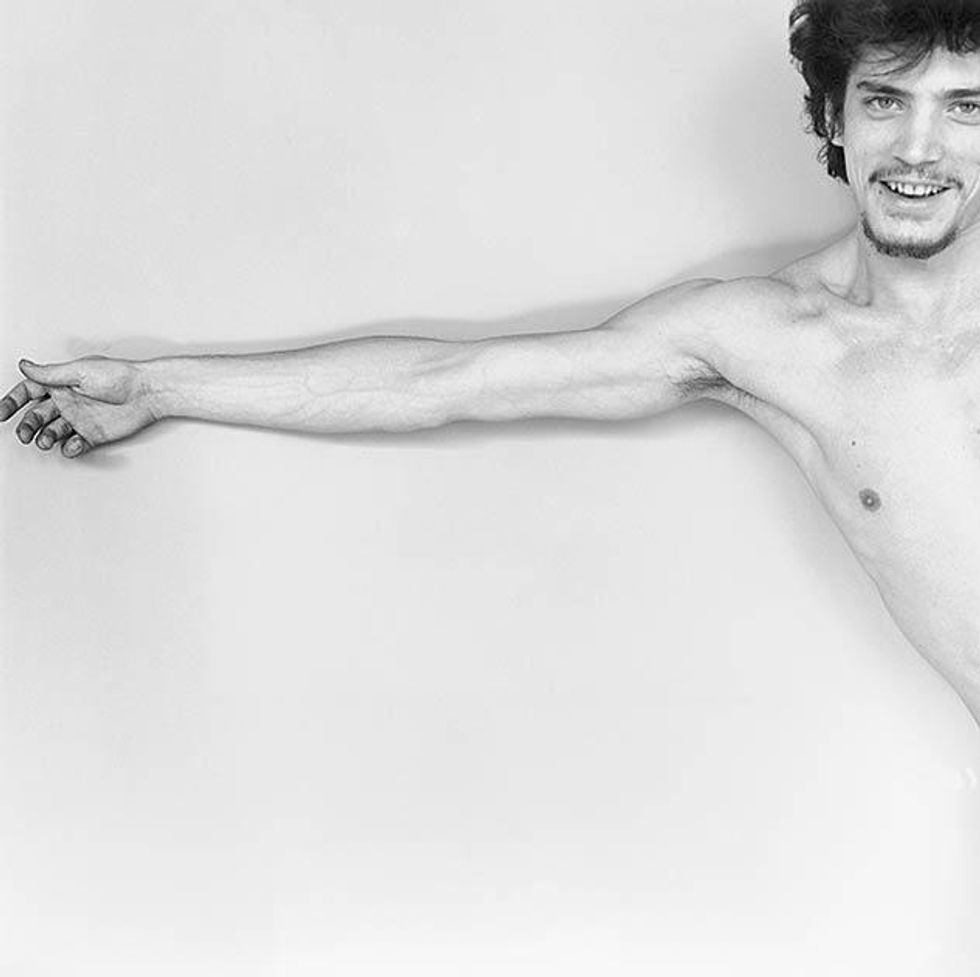

Above: Self-portrait

Above: Self-portrait

With a zest of irony and a pulse on the cultural zeitgeist, Robert Mapplethorpe's retrospective 1989 exhibition -- aptly titled The Perfect Moment -- was a rejection of the perception of gay male sexuality as abject and diseased during the height of the HIV and AIDS crisis.

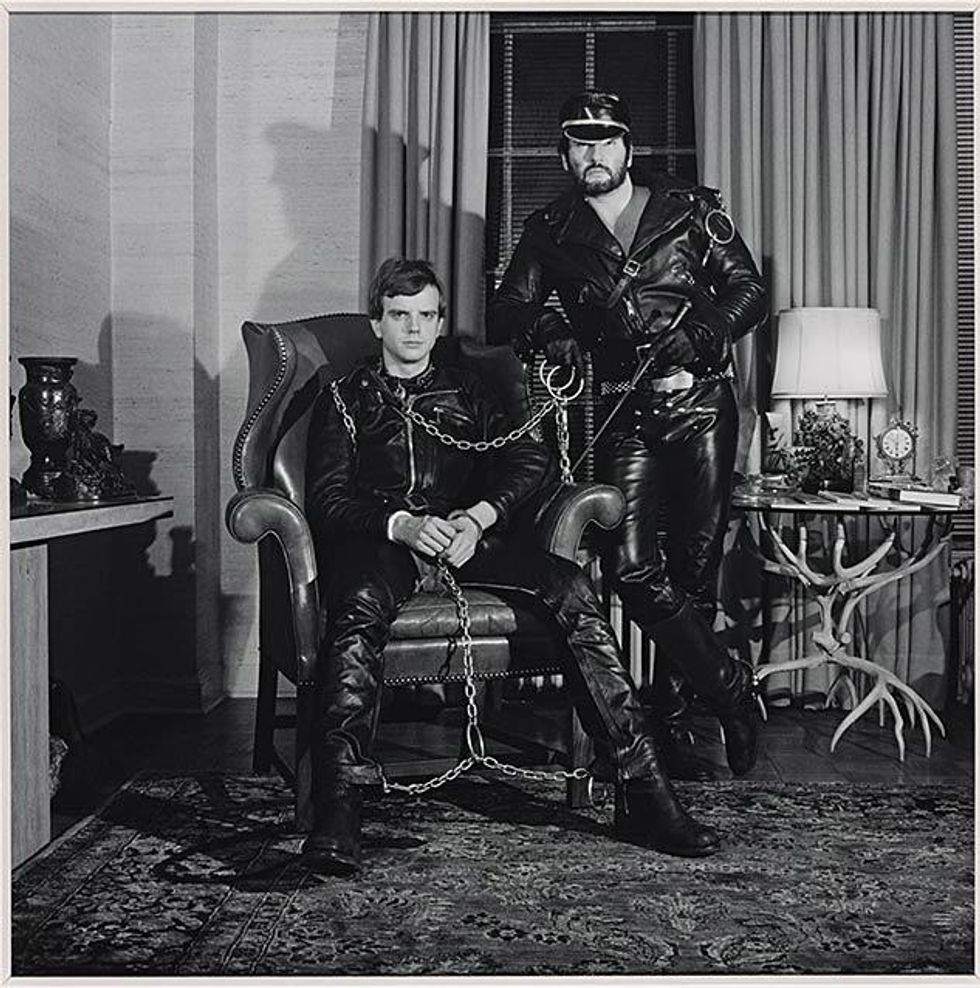

It was images of Mapplethorpe penetrating his anus with a bullwhip, and leather-clad men chained to one another, that saw the cultural wars of art and pornography bubble over 25 years ago this year. In an age of the uninterested President Ronald Reagan -- who was busy building Star Wars machines and writing checks for Nancy's White House china collection -- Mapplethorpe's retrospective exhibition The Perfect Moment entered the public realm at precisely the perfect time, signalling the end of the political conservatism and rife homophobia of the 1980s, compounded by the HIV and AIDS epidemic.

Robert Mapplethorpe is best remembered as an American photographer whose black-and-and-white work was enriched in the cultural sphere for its unapologetic representation of unadorned gay male sex. Mapplethorpe flourished in the late 1960s and '70s in New York's bohemian, avant-garde art and queer scene, and even had a brief romance with Patti Smith before becoming her most intimate confidante.

His photographs were often large-scale, and attempted to break down the normative politics dictating notions of masculinity, gay manhood, blackness, whiteness, and the need to make visible the "closeted" terms of gay male erotics. Mapplethorpe's other photography concerned itself with celebrities he photographed during the 1970s, such as Deborah Harry and Grace Jones. Like Andy Warhol, Mapplethorpe was an outlaw on the New York art scene, invested in both representing the otherwise unrepresented (gay male sex) and indulging in the camp pleasures of Hollywood celebrity culture.

Mapplethorpe began shooting as early as 1969, the same year gay men, drag queens, and transgender individuals fought back against endemic police at underground gay bars and launched a riot that sparked a movement at New York City's Stonewall Inn. As those riots symbolically marked the birth of the gay liberation movement, so too did they mark the increasing efforts for homosexual visibility in American society. While Mapplethorpe was not overtly politicized by the gay liberation movement, his photography from 1969 onwards was ostensibly driven by a desire to make visible the hidden history of gay male sexuality and erotics. Indeed, Mapplethorpe once said, "My life began in the summer of 1969. Before that I didn't exist."

This year marks a quarter-century since Mapplethorpe's most notorious exhibition, The Perfect Moment, showcased the work for which he is best-remembered -- visual moments of a frank and even confrontational homoerotic play between gay lovers. Although Mapplethorpe did not curate the exhibit, as he died four months earlier from AIDS-related illness, the exhibition enraged much of the American public, who protested the use of government funds and facilities for the presentation of his artwork. It became a hot-button political issue, and gay male sex was splashed across American newsstands throughout the nation.

Although it came to symbolize -- and reject -- the homophobic panic elicited by the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, The Perfect Moment actually displayed artwork produced by Mapplethorpe in the 1970s, taken mostly in his studio. When the images were collected for the 1989 exhibition at the Corcoran Institute of Art in Washington D.C., they were completely reorganized around a new series of meanings. In light of the changed cultural context in a society fearful of a "gay plague," these images spoke directly to issues of gay male sexuality, anal penetration, and principally the HIV and AIDS epidemic, which was still ravaging the gay community and was spread, in part, through unprotected anal sex.

The original meaning of Mapplethorpe's images (many from his "X Collection" photo folio) was to make visible the pleasures, pains, and politics of underground gay male sex and BDSM play. The iconography of Mapplethorpe's world was characterized by an active rejection of the dominant social, cultural, and indeed political representation of gay men in 1970s American life.

The dawn of the AIDS crisis in the early 1980s meant that the gains of gay liberation in late 1970s America were scaled back as the deadly virus began its vicious rampage against the gay community. By 1989, when Mapplethorpe's The Perfect Moment opened at a Washington gallery near the Capitol, the partial government funding of the exhibition garnered the attention of several U.S. Senators.

Conservative voices like Sen. Jesse Helms argued against funding for "obscenity" and "pornographic" images of "homosexuals," which featured naked children, men enacting moments of sadomasochistic pleasure, and camp recreations of royal wedding photographs.

"It is an issue of soaking the taxpayer to fund the homosexual pornography of ... Mapplethorpe, who died of AIDS while spending the last years of his life promoting homosexuality," Helms said at the time.

Above: Robert Mapplethorpe, Bryan Ridley and Lyle Heeter. 1979

Above: Robert Mapplethorpe, Bryan Ridley and Lyle Heeter. 1979

But now, 25 years later, the artistic force and political message of these images can be gleaned more pleasurably without the repressive din of the Reagan administration. One notorious image from the exhibition entitled "Self-Portrait" (1978), features Mapplethorpe inserting a bullwhip into his anus while aggressively maintaining eye contact with the camera's unflinching eye. The photograph is perhaps the most controversial of the exhibition because of its unapologetic representation of autonomous gay male sexuality.

For many, the pleasure and aesthetic beauty of "Self-Portrait" is derived from Mapplethorpe's ability to be both the object (or "bottom") and agent (or "top") of anal penetration. As gay male anal penetration is often demarcated between the "top" and the "bottom" partner, Mapplethorpe's ability to represent both deflates the dichotomy and shows him performing the paradoxical politics of gay male anal penetration. Moreover, in the process of creating a self-portrait, Mapplethorpe not only reveals the politics of self-portraiture photography -- that of simultaneous objectification and autonomy -- but also emphasizes the visibility of his anus, a traditionally unseen bodily part in our culture.

To be blunt, when Mapplethorpe shows his penetrated anus in "Self-Portrait," he rejects the cultural reticence against anal pleasure and demonstrates the importance of the anus in gay male sexual discourses.

However, this is only one image from an extensive retrospective that importantly reintroduced a new generation of gay men, queers, and art lovers to the powerful message Mapplethorpe sought to disseminate: that of privileging pleasure and pain in whatever its form through the photographic gaze.

More than two decades later, Mapplethorpe's work still endures as a perfect moment in gay history of battling backlashes against our bottoms and bullwhips.

NATHAN SMITH is a graduate student at the University of Melbourne Australia specializing in queer and cultural studies. His work has been published in The Advocate, Salon, and Out. He tweets @nathansmithr. See footage from the 1989 Perfect Moment exhibition below.

Above: Self-portrait

Above: Self-portrait Above: Robert Mapplethorpe, Bryan Ridley and Lyle Heeter. 1979

Above: Robert Mapplethorpe, Bryan Ridley and Lyle Heeter. 1979

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes