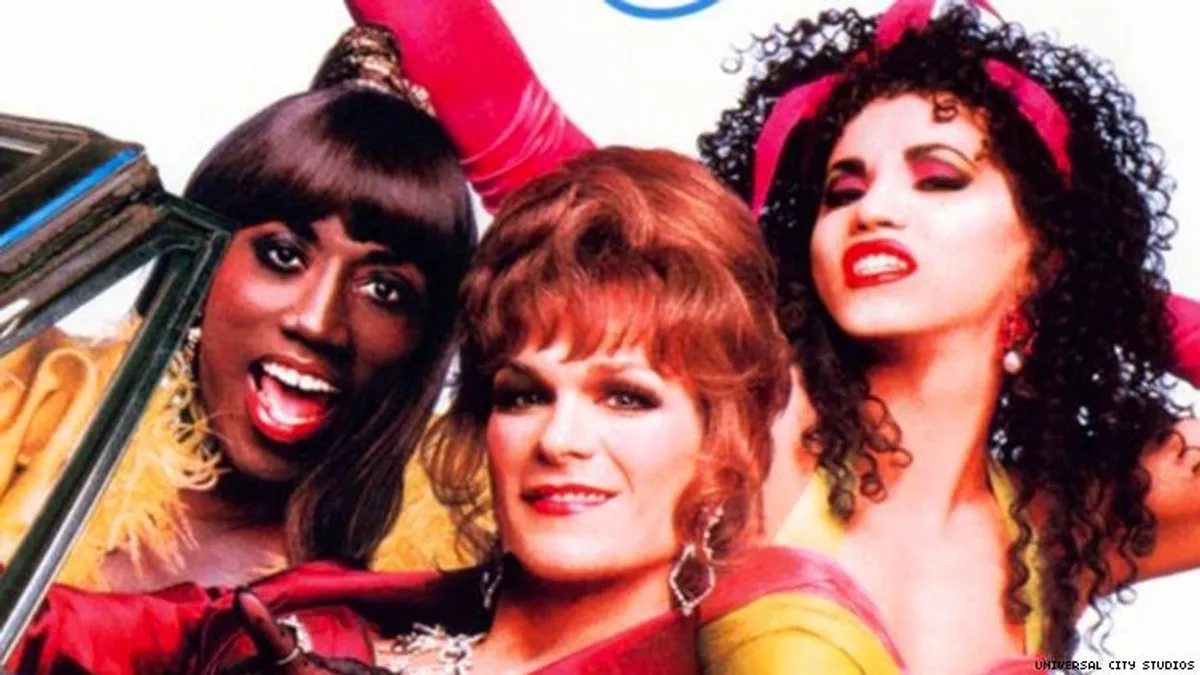

The gay executive who fought to make the drag classic To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar gives us a delicious slice of '90s Hollywood.

August 13 2015 5:00 AM EST

April 18 2019 11:46 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

The gay executive who fought to make the drag classic To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar gives us a delicious slice of '90s Hollywood.

In 1994, AIDS became the leading cause of death for Americans between the ages of 25 and 44.

The 10 top-grossing movies of 1994 were The Lion King, Forrest Gump, True Lies, The Mask, Speed, The Flintstones, Dumb and Dumber, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Interview With the Vampire, and Clear and Present Danger. That year, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, a film about two drag queens and a transgender performer, opened to strong reviews and grossed about $30 million in the United States; excellent considering the Australian film's budget was only $2 million.

In 1995, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar was released. Its plot was similar to that of Priscilla, and the reviews were decidedly mixed. And, no, the film did not deal with the AIDS crisis.

But perhaps the fact that the film didn't deal with dying men -- whom straight audiences could cry over in a theater but disdain in the real world -- and instead featured three healthy, out, proud, unapologetically gay queens made its mere existence particularly noteworthy.

This film, with three gay characters at its center, did get made, and by a major production company -- Steven Spielberg's Amblin Entertainment. It was released by a major studio, Universal Pictures. It was the number one film at the box office in its first two weeks in the theaters. And while the film itself may not have sparked much if any social change, it did have a major impact on the lives of the people associated with its making. For that alone, the film is worth celebrating on its 20th anniversary.

In 1994, I was a development executive at Amblin Entertainment. I hadn't planned on working in the movie industry, and surely not for any political reasons. I was no Larry Kramer. I was late to the gay party, in the sense that when I finally did come out in graduate school -- in 1983, at Columbia, studying playwriting, as if I were giving myself a big hint as to my sexuality -- "gay" and "AIDS" were already partnered. Hallelujah.

Leaving New York, my partner, Karl, and I moved to the Castro district of San Francisco so we could live openly. Living in the Castro in the mid-1980s was so liberating. We could hold hands in public! Kiss in public! Not have to explain ourselves to anyone!

And, of course, it was a harrowing time too. I was a member of the gay tennis league. A league full of physically fit, beautiful young men. Men who would suddenly disappear from sight, and when any of the rest of us asked where they were, the answer was always -- always -- "they died." And quickly.

Back in New York, Karl's brother died of AIDS.

Still, I entered the movie industry without a sense of political urgency, although I was "out," both in terms of my sexuality and my relationship with Karl. I started as an assistant to a lawyer at the talent agency, International Creative Management. My boss was a great guy, a totally accepting man, who called Karl my "buddy." Even though Karl and I had met just a couple of months after I started at Columbia and had been together for five years at that point, what other word was there?

I moved from that desk to being the assistant to a literary agent for film writers. Again, I was lucky; my boss was a wonderful and wonderfully accepting woman. While typing and fielding calls by day, by night I wrote coverage -- synopsizing and critiquing books and scripts for their movie-worthiness -- for various production companies and studios. One of those companies was Amblin Entertainment, and, to my surprise, the company's president, Kathy Kennedy, offered me a full-time position doing coverage there. No fool me; I took the job.

Amblin was a heavenly place to work. The people -- from Steven Spielberg and Kathy Kennedy to the receptionists -- were all so nice, and everyone was on a first-name basis. Everyone -- we all called him "Steven." There was a full-time chef and fully stocked kitchen, open to everyone's use at any time. There was a screening room complete with a constantly replenished popcorn machine and candy counter. My first job was to sit in said screening room, munching away, and watch Nazi propaganda movies and write reports on them. The short films weren't subtitled, but they didn't need to be; fast cuts between Jews wearing yellow stars and rats scuttling down sewers don't really need words to make their point.

I was accumulating background material for a film in development, Schindler's List. It was also the time of Jurassic Park. Amblin was buzzing. And very straight. I was the only gay person, man or woman, in the building. Well, the only out person.

It never occurred to me to hide my sexuality. Karl and I were living in gay old West Hollywood -- still do -- and while we were no crusaders, we just lived "out." When it came to work, being the only openly gay man at Amblin was useful. When it came time to ask for donations for the AIDS Walk, everyone sponsored me -- I had no competition for money.

As I moved up the proverbial ladder, I covered the book and theater worlds for Amblin, looking for material and promising writers. Again, the powers that be were very open to anything or anyone I sent along for consideration. As long as the material had commercial potential or a writer had real talent, I was free and encouraged to be their champion, and my voice was taken seriously.

I met Douglas Carter Beane, a very talented playwright, via his agent at the time, the late Mary Meagher of William Morris. Mary was a beautiful and quirky blond who ate her meals by hand. All of them. Mashed potatoes were scooped with two fingers and deposited in her mouth. She knew how to stand out. And she knew how to champion her clients.

Douglas told me about a script he was working on -- a comedy about three drag queens traveling across the country, in drag -- and I couldn't wait to get the finished work. Priscilla hadn't hit the radar yet, and I hadn't heard anything like the story he told me, in his own inimically comic way. I told Mary I wanted the script as soon as it was ready, and she promised me that I'd get it the day it went out.

Finally, the day came when she called to say the script was ready and heading to my office. I waited. I waited. I waited.

I went home. The next morning, I waited some more. Then I called Mary, who had no idea the screenplay hadn't come to me. She called me back and told me that the people at the agency wouldn't send it to Amblin; they thought she was crazy, that Amblin would never buy a script about three gay men.

Mary championed her clients. Mary was tough. Mary got me the script within a couple of hours.

On page 2, or maybe it was even on page 1, the black drag queen was introduced. Noxeema Jackson. The first big laugh ... of many. Less than an hour later, I called Mary. I was sending the script up the line.

Steven read the script that night -- what faith he had in me, in all of us there -- and loved it. But he needed some confirmation. It wasn't the gay stuff that worried him; he just wanted to be sure the script was as funny to other people as he found it. So he sent it to his comedy meter: Robin Williams. The verdict? Make the movie. Mr. Williams said he couldn't play the lead, Vida; he was concerned he was too hairy. But he'd do a cameo.

For the first time in years, maybe ever, Amblin was going to buy a spec script and put it straight -- pardon the pun -- into production.

Finding a director was hard. Every male director passed. Every one. The fantastic television miniseries Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit had just premiered in the U.S., and we quickly signed its female director, Beeban Kidron.

Finding actors was easy. Wesley Snipes said yes immediately; John Leguizamo, for whom the role of Chi-Chi Rodriguez was written, jumped aboard too. Many actors were interested in the Vida role, and they all consented to screen tests. While good, none of them quite clicked. Patrick Swayze's agent had been insisted that we see him, so Beeban flew to New York to meet him. Swayze had his own makeup people transform him into a woman, and he insisted that he and Beeban take a walk around the city to prove he could pass as a woman. With his beauty and dancer's grace, he did just that. He had the job.

While all this was happening with the movie, and as filming moved to a dusty small town in Nebraska, things were happening back at Amblin. Word got out that Steven had spoken well of me in a meeting. He had said that perhaps gay people were more creative because they used both sides of their brains. Steven didn't care that I was gay; he celebrated it.

And suddenly, coworkers started coming out. It was like, well, the popcorn from the machine in the screening room. A kernel erupts here, another one there, then they start flying fast and furious. People who kind of seemed gay announced themselves. The woman who had Dennis Quaid pictures pasted everywhere around her desk and who constantly talked of what she would do with him if she had the chance -- well, she was a lesbian. Straight people became hard to find, though some people were in fact heterosexual. That year, getting sponsors for the AIDS Walk became a chore. I had to look elsewhere.

I had to. One night, after falling and bleeding and "messing" himself, our friend David managed to call me. Karl and I got there and called 911. The paramedics came -- and refused to take him to the hospital. They wouldn't touch him. They gave us the number for a private ambulance and left. I didn't know they could do that. I didn't know they would do that. David died of complications from AIDS.

In September 1995, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar came out -- pardon this pun too -- and it opened at number 1 at the box office. And yet, perhaps it had been more successful than I had imagined it would be when I read the script. More seriously successful. More politically successful.

Eventually, Kathy Kennedy left Amblin and new co-presidents took her place. My contract wasn't renewed. I interviewed at a couple of studios for production executive jobs like the one I had at Amblin. But the feedback was that my sensibilities were more "independent film" than "studio film." I had gotten a gay film made, and while Steven was proud to make it, no studios saw it quite that way.

Just as I had suddenly decided I wanted to work in movies, I suddenly decided I didn't. I answered a newspaper want ad (yes, those existed once) for an English teaching job, and that's what I've been doing ever since. It's a gift working with talented high school students eager to express their opinions and tell their stories. Students who are far braver and bolder than I was at their age.

Now it's the 20th anniversary of the release of To Wong Foo, and so much has changed. Karl, my onetime "buddy," is now my husband. We married in the pre-Proposition 8 window back in 2008, though we consider October 27, 1983, the day we first met, as our real wedding date. And now all of our gay and lesbian comrades can marry too, no matter what state of the union they live in. Drag queens are a bit passe. Transgender men and women are the focus now. HIV hasn't gone away, but it's manageable, not an automatic death sentence.

None of this means, of course, that the work is all done. There are so many battles still to fight, but at least now we have straight allies.

I'm definitely no Larry Kramer; I haven't achieved an iota of what he's done for not only the gay community but the human community. Yet when I think of To Wong Foo, I don't think of merely a movie. I think of what it meant to make a movie about three out and proud gay men back in the mid-1990s. What it meant to have a major studio finance and release it. What it meant to have one of the preeminent men in the history of the film industry support it from day one, without any begging or convincing.

I think of how I didn't realize all that it meant then, and I think of all that it means still.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered