I was 13 the first time I smoked a cigarette. On a vacation to Rhode Island with my parents, I sneaked off for a walk alone. I bumped into two girls about my age, who chatted me up and offered me a Marlboro Light. I hacked and gagged while they laughed.

When I got back home from our family trip, I told my best friend -- a good Russian Orthodox boy -- about my misadventure.

"Why did you smoke a cigarette?"

I thought about it for a second. "I don't know."

The next time I smoked -- about a year later -- my motivations were clearer. After developing crushes on nearly all my male friends, I began spending more time with a mid-'90s version of a bad-girl squad. We stole street signs, shoplifted at the Gap, pilfered beers from our parents, and snuck ciggies behind a tennis center where we gathered nearly every day after school (it was Connecticut). I tried smoking again to fit in with my girl gang and to cement my growing delinquent status, which rebelled against the straight-edge male friends I wanted desperately to forget.

Sucking down that toxic air while shivering in shorts during New England winter was less than pleasurable; I hated it. So, while my girlfriends picked me up for school, exhaling plumes at 7 a.m., I would quietly abstain.

Arriving at college, I wasted no time getting falling down drunk and ingratiating myself with my R.A./local weed dealer. His friends were all straight, but not narrow; crunchy types who had goatees and talked about Freud, the Smiths, and how cool Portland, Ore., was. They all smoked. I remember seeing one of those dudes carefully place his monogrammed lighter on top of his box of Camel Wides. What a pretty accessory, I thought. I want some. Soon I was hacking my way to being a regular, cigarette-buying smoker.

As much as those hairy guys were an improvement from the keg-sucking bros who made up much of the male student body at the University of Connecticut, I didn't really fit in with them. Most of my friends continued to be women, about half of whom polluted their lungs with me.

When I began working at the school paper, my cigarettes became my Zen. Any time I was stressed, I went out for a cigarette. Any time I read or wrote an upsetting headline about Monica Lewinksy or "don't ask, don't tell" or Felicity cutting her hair, I'd smoke. My Marlboro and Parliament Lights never let me down -- and they killed my appetite, which was a major plus since I couldn't afford food and was working off the freshman 15.

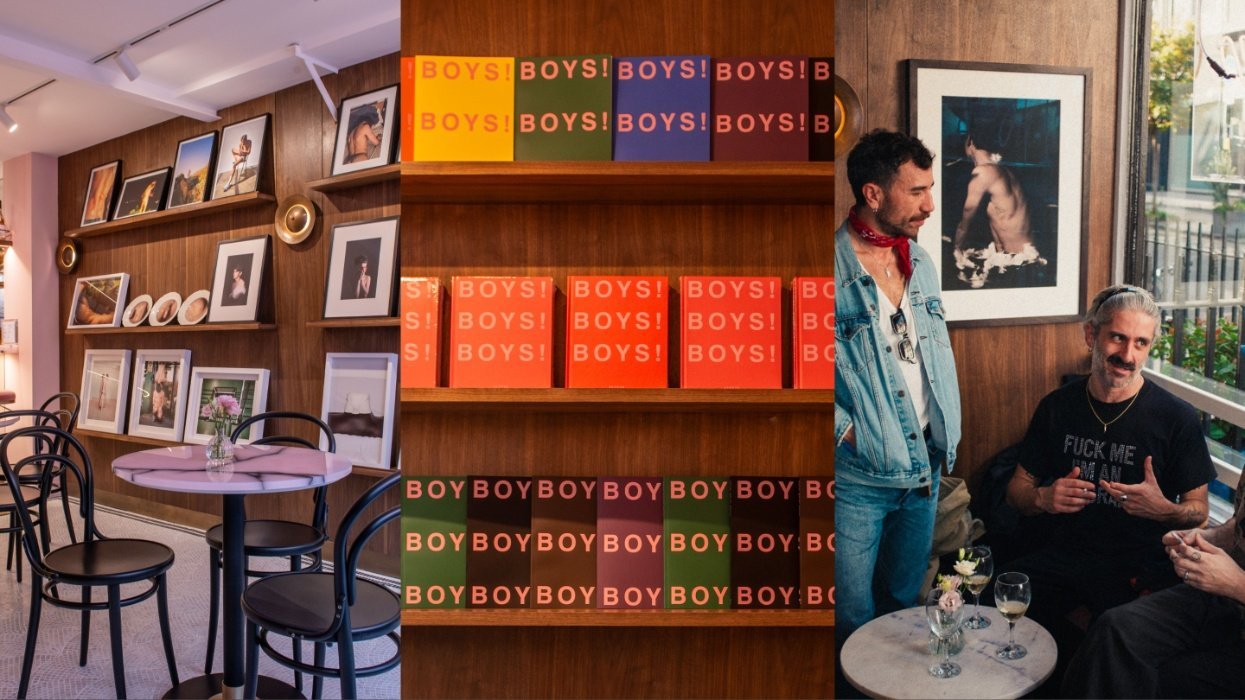

Then I turned 21 and I found out just how useful smoking can be. Venturing into gay bars in Hartford, I'd ask for the flick of someone's Bic and -- bam! -- I had a date. When we drove to the gay clubs of New York, my cigarettes were fiery armor against some of the strange, unfriendly faces that populated those dark dumps.

Moving to Los Angeles in the early 2000s meant a huge change: I couldn't smoke inside! I thought I'd hate it, but I actually enjoyed not smelling like an old-time bowling alley; I loved breaking up the evening by going outside to light up and meeting a handsome gentleman doing the exact same thing. Another plus: Smoking outside in L.A. was something you could do year-round thanks to the temperate climate. Limiting my butts to outdoors made me feel healthy and responsible, especially compared to all those East Coasters who still smoked in restaurants and watering holes.

As the years passed, I noticed fewer and fewer people venturing outside. People began turning up their noses at me when they found out I smoked. California began to change me; cigarettes started seeming gross to me too. Of course, living in L.A. made me even more hyper-aware of my appearance, which translated to a fear of smoking-induced wrinkles and yellow teeth. In my late 20s, I went on Wellbutrin and cut down my cigarette intake dramatically. I still smoked, though, especially when I drank, and definitely when I went dancing in West Hollywood or Silver Lake.

Not only did drinking and smoking go together well -- in my mind -- it was a communal experience at the gay bars. There was always someone out there ashing; sometimes a beautiful man staring off into the distance would turn his attention to me if the moment was right. Outside, we could have a conversation that was mostly impossible inside the deafening club.

For the next six or seven years, I continued smoking a pack every two or three weeks. I thought it was OK. They came in handy when I was depressed or anxious, but I still kept reducing. I got down to about a pack a month, or about one cigarette every two days. Then one day, I went on a vacation with a nonsmoker and went a week without cigarettes. I didn't think about buying another pack when I returned to L.A. So I didn't. Soon after, I met my ex-Mormon boyfriend, who hates smoking -- I knew I would never buy a pack again. With no fanfare or hair-pulling, I quit smoking after doing it on and off for over two decades. It's a quiet pride I carry with me every day.

My cessation method worked for me, but I know everyone is different; cold turkey works for some, while others need pills or a nicotine patch (head to Smokefree.gov for quit tips). I don't judge anyone who still smokes, but I sincerely hope all puffers -- especially gay ones like me who often pick up the habit to fit in or find a crutch -- discover a way to quit. No one likes to talk about it, but LGBT smoking is an epidemic. The National Adult Tobacco Survey recently uncovered that tobacco prevalence among LGBT people is 50 percent higher than any other population.

For many gay people like myself, cigarettes constitute one of the most enduring relationships in our lives and, as in Stockholm Syndrome, we've convinced ourselves we need this abusive partner. You're better off alone.

NEAL BROVERMAN is the executive editor of The Advocate. Follow him on Twitter @nbroverman.