"So, you're a lawyer, right?" The question came from my hairdresser, Tony, as I sat down for a haircut. "Do you know anything about immigration?"

I knew a little bit about Tony's story. His parents brought him to the U.S. illegally when he was a young child so that he and his siblings could have a better life. As a teenager, Tony identified as gay and won political asylum when an immigration court found that his life would be in danger if he returned to Mexico as a gay man. Now in his mid-20s, he is on the verge of becoming a U.S. citizen.

On this particular day, Tony was concerned about his older brother, Jorge, who had hoped to apply for President Obama's expanded program called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. "He doesn't know where to go for help. Can you help him?" He continued, "And my mother, she still does not have legal status. What can she do?"

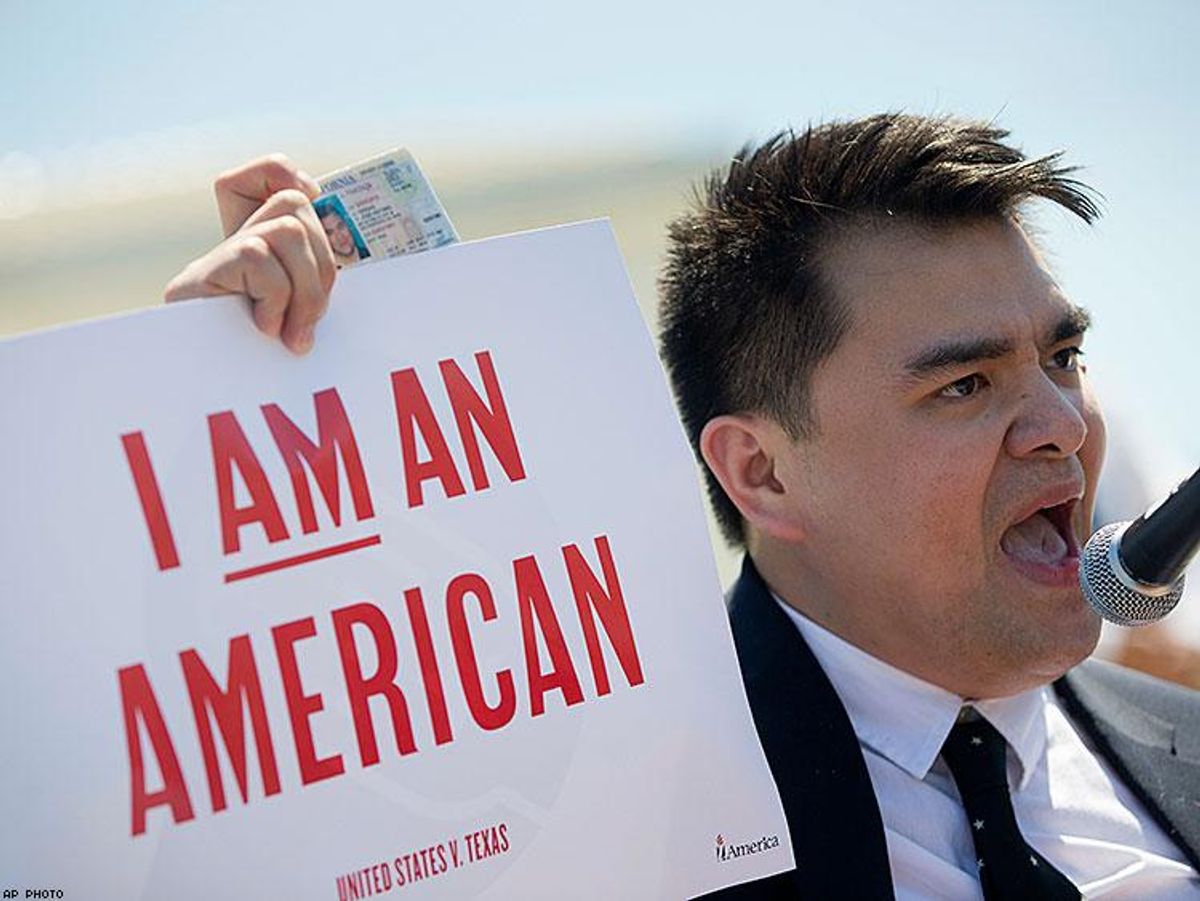

I was at a loss. The problem is that people like Tony's mother, parents of children who are legal permanent residents or U.S. citizens, and his brother, who was too old to apply under the first round of DACA, are in limbo until the U.S. Supreme Court issues a decision in United States v. Texas, which will determine whether President Obama's immigration programs can go into effect.

In November of 2014, after years of frustration with Republicans in Congress who had blocked comprehensive immigration reform, President Obama announced a new policy to address the situation of people like Tony's mother and brother. The president's program, called Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, would allow approximately 4.1 million undocumented immigrants to stay in the country for three years and work here legally if they (1) have children who are U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents and (2) have been in the United States since at least January 2010.

The president also sought to expand the DACA program for about 300,000 people who, like Tony's brother, were too old to benefit from the original initiative.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services were set to begin accepting DAPA applications in May 2015 when the state of Texas filed a lawsuit to stop the new program. In February 2015, a judge in Brownsville, Texas, blocked the program while the case was being heard. A few months later, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the policies were "manifestly contrary" to the Immigration and Nationality Act, and President Obama asked the U.S. Supreme Court to weigh in.

The Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments in the case yesterday, now has the power to decide the fate of millions of families. Many of these families have mixed statuses, meaning that some members are here legally (like Tony) and some members are not (like Tony's mother and brother). Many are young adults who were brought here by their parents as children. Others are the undocumented parents of children who were born here or who have become legal permanent residents.

While the lives of these families hang in the balance, this case raises the stakes on two important political issues as well. The first is the scope of the president's executive power, a power that President Obama has frequently used to in the face of congressional inaction in arenas beyond immigration, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights, contraception, climate change, and gun control. Second is the disenfranchisement of the newly legalized immigrant electorate in an effort to minimize the effect they may have on the 2016 election and beyond. And we should all be concerned about these outcomes, as the consequences of a loss are sure to be dire for the politically unpopular and powerless.

ARCELIA HURTADO is NCLR's immigration policy adviser.