Voices

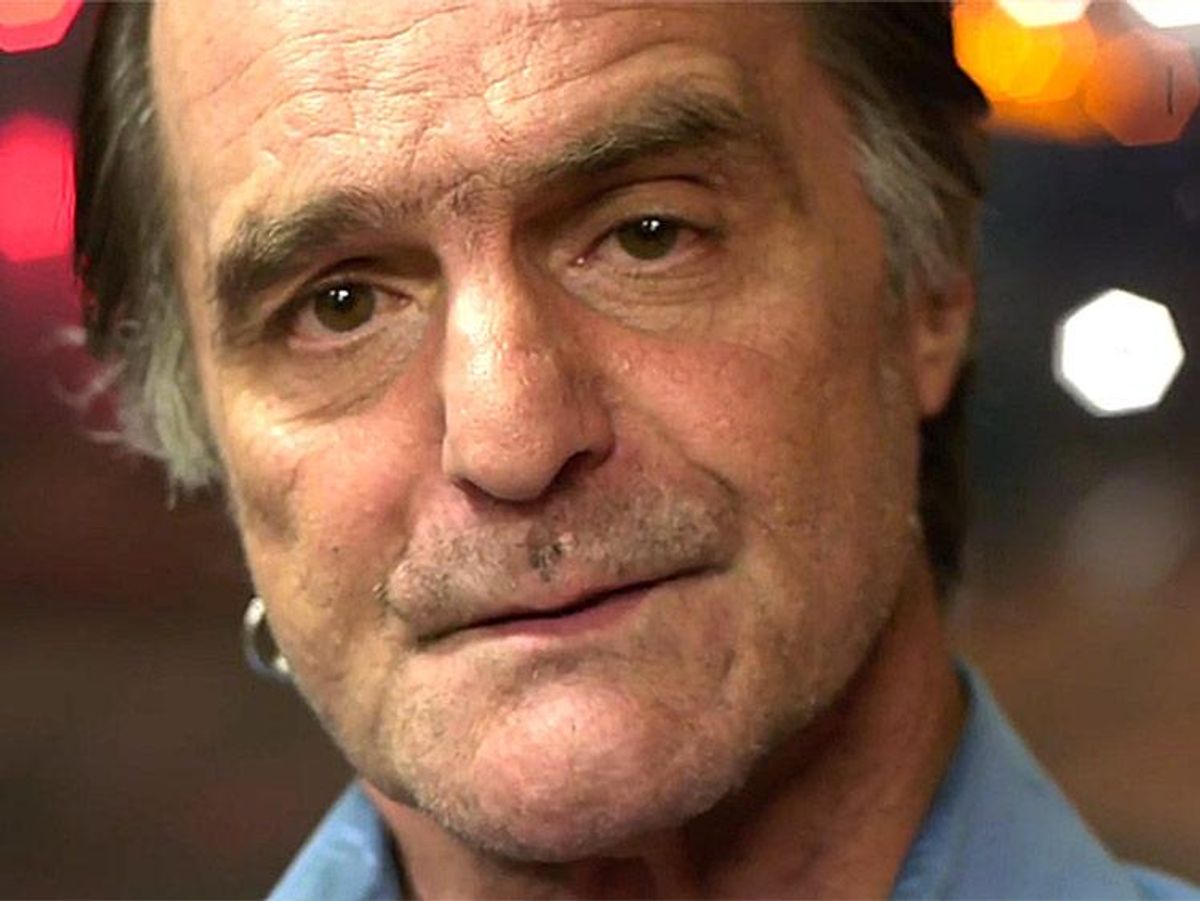

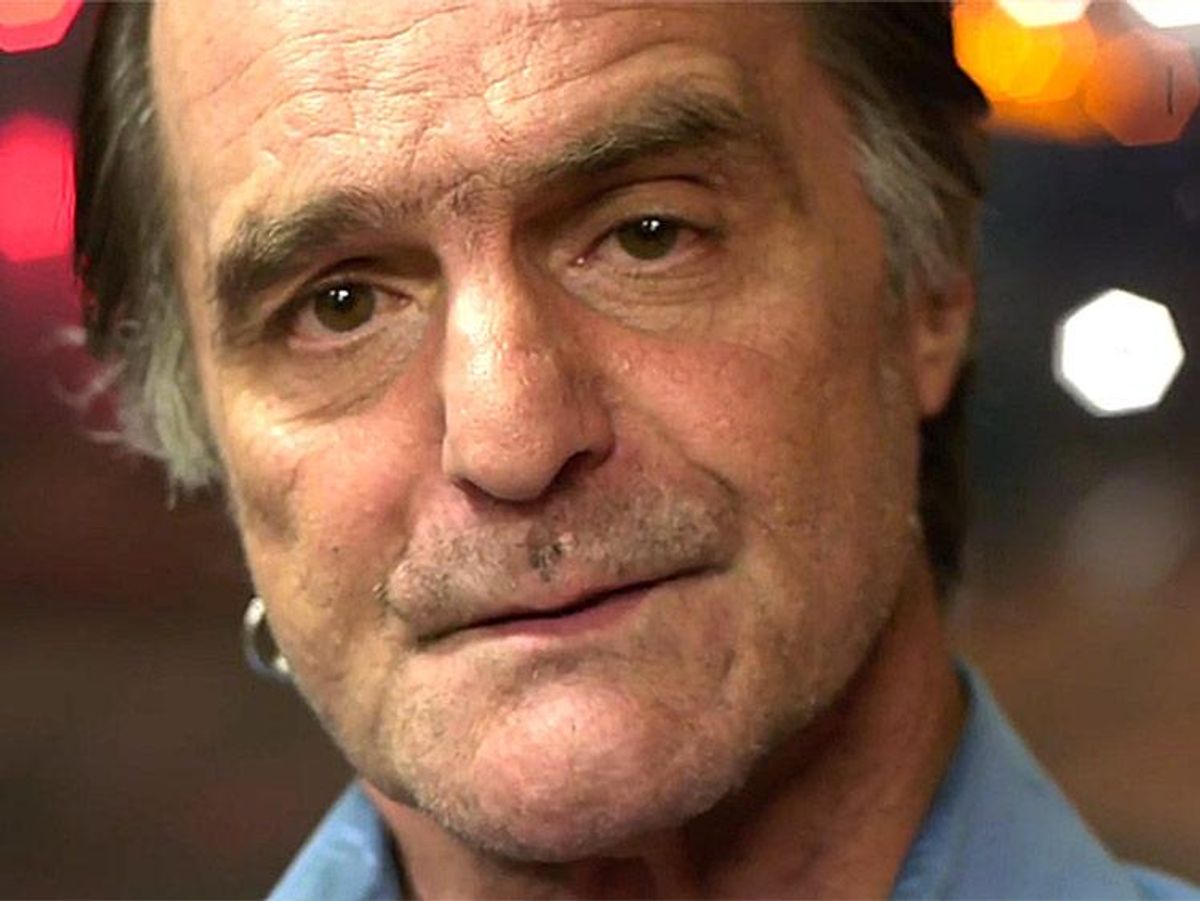

A Lover and a Fighter: The Legacy of Jeffrey Montgomery

After losing his partner to a hate crime, Jeffrey Montgomery found some solace by becoming a fierce advocate for change.

Cathy Renna

July 25 2016 1:04 AM EST

October 31 2024 7:05 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

After losing his partner to a hate crime, Jeffrey Montgomery found some solace by becoming a fierce advocate for change.

This past week the LGBT community lost someone who had an extraordinary impact in his home state of Michigan and nationally, someone who helped destroy the myth of the "gay panic" defense and changed the way anti-LGBT hate crimes were addressed by activists, in courtrooms, and by law enforcement. The loss of Jeffrey Montgomery, founder of the Triangle Foundation (now Equality Michigan), after a long struggle with health issues has been felt by colleagues, family, and friends -- and all those who fell into the intersection of those groups. I was fortunate to be one of them. His legacy is one we should all know about.

"The personal is political" is a phrase we hear all the time. But for Jeffrey it has particularly important meaning. Imagine this: losing your boyfriend to a hate crime, a brutal shooting outside a bar. This was what happened to Jeffrey's boyfriend, Michael, in 1984, and to make it even worse, the police coldly told Jeffrey it would not be investigated as a hate crime because it was "just another gay crime." This propelled him into a life of activism, in particular fighting for fair treatment by the police and increased awareness of hate crimes.

I got to know Jeffrey well in the mid-1990s while working at GLAAD and when the national media couldn't take its eyes off what was called "the Jenny Jones Murder," a sensational hate crime where talk TV was taken to task for the "I've got a secret" theme it played on -- in this case it was "You have a secret admirer." Producers saw as a rating bonanza when they found a gay man willing to admit to his supposedly straight acquaintance that he was attracted to him.

So in March of 1995, Scott Amedure, a young gay man, was fatally shot after revealing on The Jenny Jones Show that he was attracted to an acquaintance, Jonathan Schmitz. National headlines and Court TV ran with the story, from the initial trial where Schmitz was found guilty of second-degree murder -- a verdict that was subsequently overturned by the Michigan Court of Appeals -- to the Amedure family suing The Jenny Jones Show for wrongful death.

As the show originated in Detroit, Jeffrey was in the eye of the storm and became the face of the LGBT community. The story was extremely complex, with Schmitz's instability and the fact that there were conflicting reports about whether or not the two men actually did have a sexual relationship. But through it all, Jeffrey provided a clear and strong voice that dealt with everything from "gay panic" to judgmental attitudes about our community to outright sensationalism of the situation. He became a national face for the community at a time when there were few.

In 1998, I was immersed in the aftermath of the murder of Matthew Shepard, and as the trials approached in 1999, it was understood that Aaron McKinney, one of the accused, was going to attempt to use a "gay panic" defense.

Now thoroughly debunked legally, the specious "gay panic" defense was then used often, and often successfully. I immediately called Jeffrey and asked him to come to Laramie, Wyo., to assist in educating the media, the public, and the courts to the extent we could. It was the highest-profile anti-LGBT hate crime in history. and he knew how important this was, immediately coming to help. I do not think we would have seen the important progress we did in the years that followed if not for Jeffrey's hard work and dedication to the truth.

But the great irony to me, as one of many who also knew Jeffrey as a chain-smoking, black coffee-drinking, high-energy, insatiably curious man who had a wicked sense of humor and never saw a book -- or a good-looking guy -- he could resist, was that he was completely motivated by love and never lost his sense of goodness and humor, despite personal and professional tragedies.

Jeffrey knew that our movement was one based on freedom and love, not fear and hate. He was a role model in his confidence and pride in who he was, in every way. He was fearless and honest about his own struggles with loss and addiction, and quietly helped so many others deal with their struggles.

His work on sexual freedom, primarily through the Woodhull Freedom Foundation, was very important to him. Jeffrey saw sexual freedom and the end of our internalized homophobia, transphobia, sexism, and sexual shaming as key to our progress. In that way we taught me a lot. Now whenever I say, as I often do, that we live in a country that "uses sex to sell everything but refuses to talk honestly about it," I will smile, knowing that Jeffrey was a part of my learning that lesson.

Jeffrey's legacy in Michigan as the founder of the Triangle Foundation and an activist in a state where the LGBT community continues to be challenged by large and organized anti-LGBT groups is immeasurable. I will never forget the first time he took me to the foundation's office and showed me the bullet holes in the window after an attack that injured one of the group's volunteers. That same volunteer was there to greet us when we entered.

It's often hard to imagine how far we have come in the past few decades, but looking back on Jeffrey's life gave me pause, remembering a friend who overcame unbelievable obstacles to make a difference, who created community and family, and who lived an authentic and meaningful life. He was a rare person, and he will be missed.

CATHY RENNA is a media relations professional specializing in LGBT clients and a managing partner in the public relations firm Target Cue LLC.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella