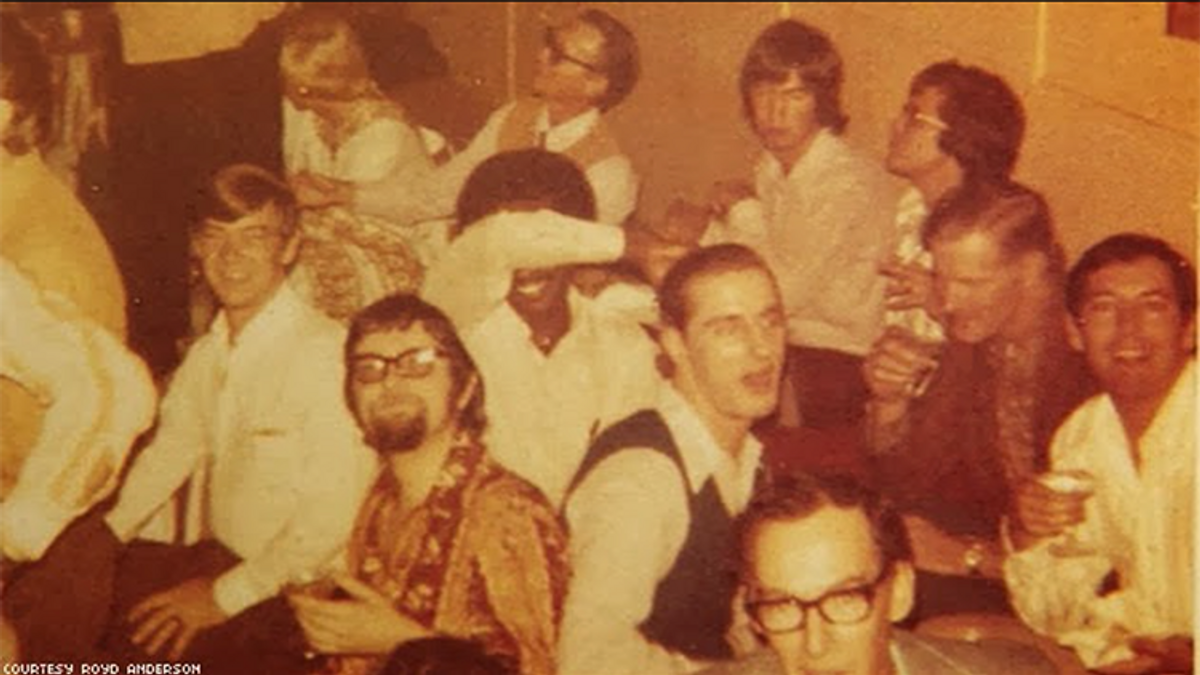

Above: For patrons of the UpStairs Lounge, the place wasn't just a bar. It was a theater, a place of worship, and a community center all in one; most important, it was a place for folks to call home when the rest of New Orleans wasn't so welcoming.

When Duane Mitchell was 11 years old, he and his 8-year-old brother, Steve, loved visiting their dad, George, then a divorced beauty supply salesman in New Orleans. The Big Easy in the 1970s was a different world compared to where they lived with their mom in northeast Alabama. Though the divorce was amicable, it was always hard for the boys to get enough time with their dad during the school year.

Sunday, June 24, 1973, started out like any other day for the boys, who were eager to see a Disney movie, The World's Greatest Athlete, starring Jan-Michael Vincent as a Tarzan-like runner over a decade before his TV series, Airwolf, would make him a household name. George Mitchell dropped the boys off at the theater like he often did. Despite the recession, gas shortage, and racial tensions that dominated that summer, it was still a more innocent time. Kids could go to movie theaters alone with a handful of cash for popcorn, candy, and sodas, armed only with the admonition to stay there until their parents came back to pick them up. Dad was going to hang out wherever it is that adults hang out, with friends and his roommate, Horace, a barber. Duane gave it little thought -- until the movie was over. And over again.

Duane says he and Steve watched that movie seven times and Dad just never came back. Finally, George's landlady picked the boys up that night, and the next day a neighbor took them to the airport to fly home to Alabama, all the while not telling them the ugly truth of why Dad never returned.

Duane says he and Steve watched that movie seven times and Dad just never came back. Finally, George's landlady picked the boys up that night, and the next day a neighbor took them to the airport to fly home to Alabama, all the while not telling them the ugly truth of why Dad never returned.

How do you tell an 11-year-old that his father was burned alive, his body wrapped about his boyfriend, the two men charred and clinging to each other, lovers in life and death, while trying to escape the worst mass killing of gays in American history?

Photo: George Mitchell (left) and his boyfriend, Horace Broussard, in happier times. George initially escaped the fire but went back in to save Horace; the two died together. George's son Duane didn't know his dad was gay but calls him a hero today.

GAY PRIDE IN THE '70S

It was the swelteringly humid last day of gay pride in the South's most tolerant city, and the fourth anniversary of New York's Stonewall Riots -- an action thought unnecessary in New Orleans. As Clayton Delery, author of the upcoming book Nineteen Minutes of Hell, told The Huffington Post's Gay Voices, "Things on the surface weren't as bad as they had been in New York in 1969. It had been several years since there had been a mass raid of a bar or a gathering place. Gay people lived in relative peace. So, in some ways, people were comfortable."

At right: Pianist George Matyi wasn't a regular performer at the UpStairs Lounge, but the night of the fire he took the gig as a favor to a friend. He left behind a daughter and two sons who only recently learned the truth of his death.

At right: Pianist George Matyi wasn't a regular performer at the UpStairs Lounge, but the night of the fire he took the gig as a favor to a friend. He left behind a daughter and two sons who only recently learned the truth of his death.

But that night and ensuing weeks would prove the city was anything but comfortable with gays.

The UpStairs Lounge was always hopping on Sundays. There was a beer bust each week, and $1 admission got you unlimited free pitchers of beer. The jukebox rotated everything from rock star Elvis Presley to opera star Enrico Caruso. Cocktail pianist George Stephen Matyi, whose regular gig was at the nearby Marriott, was there playing his signature mix of show tunes and ragtime, filling in for a friend, and possibly leading bar patrons on a sing-along to one of their favorite anthems, the Brotherhood of Man's 1970 hit, "United We Stand."

Phil Esteve opened the bar nearly three years earlier on Halloween with help from a friend, bartender Buddy Rasmussen, according to author Johnny Townsend, the only person to fully document the tragedy with survivor input in his book Let the f****ts Burn. Townsend writes that because the club was outside the gay area of the French Quarter, the men worked extra hard to draw people in with dancing, singing, and live piano by popular cocktail lounge musician David Gary. The place had red wallpaper and almost-girly curtains, creating a sanctuary that was both homier than modern bars and more welcoming than many of the patrons' homes. There was an extra space in the bar, a theater of sorts, where they staged "nelly plays" and musicals. Esteve also let members of the Metropolitan Community Church, the only LGBT-affirming Christian church in the nation, use the space.

At left: Bartender Buddy Rasmussen (right, with a friend) led 20 people to safety but inadvertently locked the door behind them, closing off the only escape route.

At left: Bartender Buddy Rasmussen (right, with a friend) led 20 people to safety but inadvertently locked the door behind them, closing off the only escape route.

It was a happy place for the members of MCC, the mainline Protestant church founded by Rev. Troy Perry in Los Angeles in 1968. As the denomination spread nationwide, fledgling MCC congregations formed in places like New Orleans where religion was a cornerstone of community life. Though the Christian worshippers were as devout as any flock in the South, a church run by gay, bi, and transgender people wasn't wholeheartedly welcome in the local community. In fact, the UpStairs Lounge had served as its temporary place of worship for months because the church had been set ablaze three times, including, according to Townsend, a fire that destroyed its headquarters January 27, 1973.

But Esteve and bartender Rasmussen liked having churchgoers at the lounge. They added to the friendly environment of the club, a place where at least two patrons, brothers Jim and Eddie Warren, felt comfortable enough to bring their mother, Inez.

Above: Rodger Nunez, the main suspect in the mass killing, pictured in life and in death.

On Sunday June 24, 1973, more than 100 people attended the MCC service, and dozens stuck around to plan an upcoming fundraiser for what then was called Crippled Children's Hospital. Esteves gave them all free beer. It was a night like any other. Oh sure, there were vagabonds, says filmmaker Royd Anderson, whose documentary The UpStairs Lounge Fire details that night and the aftermath. But there were also doctors, poets, actors, intellectuals, and hustlers.

At left: Duane Mitchell (left) looks at photos of his dad, George, with filmmaker Royd Anderson. Duane was 11 years old at the time of George's death.

At left: Duane Mitchell (left) looks at photos of his dad, George, with filmmaker Royd Anderson. Duane was 11 years old at the time of George's death.

One of those miscreants was Rodger Nunez, a 26-year-old hustler who often became aggressive and mouthy when he was drunk. This night Nunez began to harass one of the regulars, Michael Scarborough, through an adjacent stall in the bathroom. Who knows why Nunez was acting out then? There was a glory hole in the restroom, but Scarborough didn't want anything to do with what Nunez had to offer. When the altercation turned physical, Scarborough gave the guy a right hook to the jaw, and when that didn't stop him, he complained to Rasmussen, who sent Nunez packing. As he was escorted out, Nunez spouted off a threat of revenge typical of someone being kicked out after a bar fight. The hothead was posturing, the patrons probably thought; good riddance.

At 7:52 p.m. the doorbell, located down a stairwell at the first-floor entrance to the second-floor bar, began to ring. Rasmussen assumed it was a taxi driver, as it usually was, so he sent a regular named Luther Boggs down to open the door. It had been more than a year since the last gay bar raid, but you could never be sure, hence the added security. Boggs probably had no idea what hit him. He was dead instantly.

A flash of fuel hit the landing and then a fireball swept up the stairwell into the bar, flames quickly engulfing the place. More than 60 people were still there, and the fire spread so quickly that panic was unavoidable. The oxygen from the door had created a backdraft that swept the fire along the hallway blocking the main entrance, and it sped along the walls rapidly. Those curtains, flocked wallpaper, and, even the lone poster of the famous Burt Reynolds Cosmopolitan centerfold that had been tacked up were all gone in seconds. There was no emergency exit sign. People clamored to get out, some pulling their clothing over their mouths in hopes of breathing through the smoke. Glass shattered everywhere as patrons tried to escape through the windows; few were skinny enough to do so, because the windows all had 14-inch security bars.

At right: MCC pastor Bill Larson, trapped in the window bars, where he remained for hours during the investigation. He was promoted to reverend posthumously.

At right: MCC pastor Bill Larson, trapped in the window bars, where he remained for hours during the investigation. He was promoted to reverend posthumously.

The pastor of MCC, Bill Larson, was caught in the bars, the upper half of his body stretching for an impossible escape as he burned alive, his agonizing wails heard by onlookers on the street. "Oh, God, no," he screamed as horrified onlookers watched the man die.

Harold Bartholomew was driving past the bar with his kids when they noticed flames shooting out of the building. He rushed to help but was useless. He told Anderson, "People were at the window cooking -- that's the only way to describe it," pieces of flesh literally landing on the sidewalk below in a scene so terrible, "I don't want to talk about it anymore."

"Bartender Buddy Rasmussen led about 20 people to safety through a back door behind a stage," Anderson says. "But investigators found he unintentionally trapped the remaining bar patrons when he locked the fire escape door to prevent the fire from spreading."

George Mitchell, 11-year-old Duane's dad, was the MCC's assistant pastor then. He was one of the few people who managed to escape the fire, but when he realized his boyfriend, Louis Horace Broussard, was still trapped inside he rushed in to rescue him. The two were found dead, bodies wrapped around each other, together forever, a gruesomely romantic scene.

Above: Victims of the UpStairs Lounge fire on June 24, 1973

Firefighters -- including Terry Gilbert, a rookie only two weeks on the job -- arrived quickly and had the fire contained within 16 minutes. No matter, though. They discovered 28 dead bodies piled up in grotesque mounds atop each other at the bathroom door, the fire escape door, and the windows, any place they could have hoped to escape. Four more people would die either en route to or at the hospital. In all, 32 people were killed that day, and though a few might have been straight, like that pre-PFLAG mom and the friendly substitute pianist, this tragedy still remains worst mass murder of LGBT people in U.S. history.

The grisly fire was just the beginning of the tragedy that would affect New Orleans's LGBT community for years to come. All of which raises the question: Why have so few people even heard about this?

THE AFTERMATH"Louisiana does a pretty good job of keeping its tragedies a secret," says Anderson, who became an expert on the killings when he spent six years filming his award-winning documentary The UpStairs Lounge Fire, which aired this summer on television in New Orleans and continues to tour festivals and universities. Next up is a November 21 showing at New Orleans's Loyola University and then a collegiate screening tour that'll take Anderson to Penn State, Louisiana State University, Yale, and Princeton.

The Cuban-American filmmaker has produced documentaries about several forgotten Louisiana tragedies: the 1976 Luling Ferry disaster (the worst ferry disaster in U.S. history, with 77 fatalities), the 1977 Continental Grain Elevator explosion (the deadliest grain dust explosion of the modern era, with 36 fatalities), the 1982 Pan Am Flight 759 crash (the worst aircraft crash in Louisiana history and the fifth worst in U.S. history, with 153 fatalities). The UpStairs Lounge fire fits among them: It remains the deadliest fire in New Orleans history.

At left: Filmmaker Robert L. Camina in front of the plaque memorializing the UpStairs Lounge massacre.

At left: Filmmaker Robert L. Camina in front of the plaque memorializing the UpStairs Lounge massacre.

"All of these tragedies, in addition to the UpStairs Lounge fire, aren't in textbooks," he says. "Plus, a lot of LGBT history is not that well publicized in the Bayou State. There's a small plaque on the sidewalk outside of the former door of the UpStairs, commemorating the victims. If you're not looking down when you're walking, you won't even notice it. Thousands of tourists step on it every day and don't realize it's there."

Anderson learned about the fire as a kid. His dad, a French Quarter tour guide, would take Anderson on long walks in the Quarter, and he would point out the building and tell the story.

"Being a social studies middle school teacher, I thought it was imperative to remember this forgotten tragedy and lost history," he says.

The teacher-turned-filmmaker is not alone. Gay author Townsend, who wrote about the tragedy two decades ago, was able to talk with many survivors of the fire, no easy feat, says Anderson, who admits getting people to talk about it today is difficult.

"Most of them didn't want to get in front of the camera and talk, due to mental strife," Anderson says. "Also, many folks from that generation don't want to be known to be gay to the public; the peer pressure is still evident today."

Toni Pizanie, who authors a column called Sapphos Psalm for Ambush, the local gay paper, wasn't at the UpStairs Lounge that night but says it happened while she was still in the closet and it made an impact on her. "I refused to attend the memorials," she writes. "I told gay acquaintances, I didn't know anyone that died. Why attend? The truth is that I was frightened. There was my great job as department head of accounting for a national firm. And, I was purchasing my first house. I didn't want my being a lesbian to mess up my future."

In 1998 she helped organize the 25th anniversary memorial. She had come out by then. But 1998 was a far cry from 1973.

THE FUNERALS

"Sadly, the gay community was used to being ostracized. It was a way of life back then," says Anderson of the atmosphere after the fire. "The early 1970s were dripping with homophobia. Homosexuality was removed from the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in December of 1973 -- six months after the UpStairs Lounge fire. Louisiana had a Crime Against Nature statue passed in 1974, making sexual acts between gay couples illegal."

It was amid this atmosphere that LGBT people in the city had to grieve and bury their dead, something that became difficult in the days after the tragedy.

Rev. Troy Perry flew in from Los Angeles, reeling from the fact that the fire had decimated the local congregation of his church. He was joined by Morris Kight from the Los Angeles Gay Community Services Center, Morty Manford from New York's Gay Activists Alliance, and two other MCC leaders, John Gill and Paul Breton. Their appearance in the city marked the first time national gay leaders gathered to mourn a tragedy, something that could have been galvanizing or healing.

They were turned away by every church in the city, however, and finding a place to hold memorial services was a unexpected battle.

"I was shocked at the disproportionate reaction by the city government," says Robert L. Camina, writer and director of the upcoming feature film Upstairs Inferno. "The city declared days of mourning for victims of other mass tragedies in the city. It shocked me that despite the magnitude of the fire, it was largely ignored. The city didn't declare a day of mourning. They were silent. I was also shocked at the religious response. Some said the response revealed the moral bankruptcy of churches. I can't imagine a church, much less several churches, turning away mourners or victims. I was also sickened by the callous nature in which the press covered the fire, if they covered it at all."

Indeed, as Perry and others searched for a church to hold services for the 32 victims, the LGBT community looked to local politicians, the mayor, religious officials, and civic leaders to at least recognize the tragedy. None did. The CBS Evening News was the only national mainstream news outlet to cover the story (The Advocate's following issue featured the tragedy on the cover, with reporting from New Orleans).

"This was before the 24-hour news cycle and the advent of social media," says Wayne Self, writer and composer of the musical about the killing, Upstairs, which made its debut in New Orleans last summer. "Today, there is simply more airtime to fill. I talked to people who had actually covered the fire and the sense I got was that they wanted the coverage to be on par with any coverage of any fire, which was a fair-minded approach. But that approach failed [to take] into account the social ramifications and the larger context of this particular fire. Of course, this early in the LGBT movement, I think it's understandable that the media would seek fairness in coverage over a social context that was barely visible to anyone."

New Orleans local media covered the story on day one without mentioning that the lounge was a gay bar. When that fact was discovered, the reporting turned ugly at times.

One local radio jockey joked, "What will they bury the ashes of queers in? Fruit jars." The joke was retold countless times around "respectable" offices in the city. The newspapers printed quotes from ordinary citizens riddled with homophobia, including "I hope the fire burned their dress off," and "The Lord had something to do with this."

Police say they did their jobs, but even the chief detective on the case, Henry Morris, told the local States-Item newspaper there wasn't a lot of hope for identifying the victims, saying, "We don't even know these papers belonged to the people we found them on. Some thieves hung out there, and you know this was a queer bar."

It was true some gay men did carry false identification at the time -- that way, if they were arrested their real names wouldn't go on the public record, something that would get you fired -- but almost all the victims were identified in the following weeks.

At left: Author Johnny Townsend (left, with filmmaker Royd Anderson) wrote about the fire 20 years ago. Because of the age of many survivors, Townsend is thought to have been the last person to really record many of the survivors' stories.

At left: Author Johnny Townsend (left, with filmmaker Royd Anderson) wrote about the fire 20 years ago. Because of the age of many survivors, Townsend is thought to have been the last person to really record many of the survivors' stories.And they were mourned. While Baptist, Catholic, and Lutheran congregations refused to allow memorials to be held in their churches, a closeted gay rector at St. George's Episcopal Church, Father Bill Richardson, allowed a small prayer service be held there. It nearly cost him his job, as the local bishop forbade him to hold further services for these (mostly) gay victims. Eventually, St. Mark's United Methodist Church allowed an official memorial service, which attracted about 250 people, though many LGBT people were too afraid to attend.

"From what I've been told by people who lived through the horror, the aftermath of the fire was very difficult," says Camina. "Friends of the victims and community members could not grieve openly. They would risk outing themselves. Not only could they lose their job and their home, they could lose their family. Their thoughts were, Look what happened to these victims. If a parent could abandon their child even in death, what will my family do to me? The list of the victims expands far beyond those who were in the bar that tragic night. The fear it generated caused many people to stay in the closet, permanently altering their lives. The extent of indirect pain and damage caused by the fire is immeasurable."

Self says, "The New Orleans gay community, though it was growing in numbers and political awareness, was not ready to turn this into a Stonewall moment. The tragedy was too swift, deadly, and profound to have it spun immediately into activism."

Like others, Self argues that straight New Orleans had come to a "quiet acceptance of homosexuality as just another sin in Sin City, but was not yet ready to see LGBT people move from the back room to the streets."

That is perhaps why civic leaders remained mum.

"The deplorable actions of the local politicians at the time was disgusting," Anderson says. "Gov. Edwin Edwards and New Orleans mayor Moon Landrieu made no statement of public sympathy for the victims. They chose politics over what was right."

Self concurs: "The government's silence was more problematic [than the media's]." He says that Clay Delery's upcoming historical book about the fire and its aftermath, The UpStairs Lounge Arson: Thirty-two Deaths in a New Orleans Gay Bar, June 24, 1973 (McFarland Publishing, 2014), "carefully compares state and local government reactions to the UpStairs Lounge Fire with their reactions to other fires or similar disasters that occurred that same summer. It's a pretty damning portrait of a city government that had no interest in mourning the loss of its LGBT citizens. That has certainly changed. The city was a great ally in memorializing the victims this year, in conjunction with New Orleans Pride and with us."

THE REVOLUTION THAT DIDN'T HAPPENSelf, the man behind the musical, Upstairs, first learned about the tragedy while working as a music director for the Metropolitan Community Church.

"I was reading MCC founder Troy Perry's book Don't Be Afraid Anymore," Self recalls. "His book is pretty critical of the community's response -- not just the government, but also the gay community. When you're from a place like Louisiana, your first instinct is to defend it against critics. So my first reaction was disbelief, not that the fire had happened, but that the community had reacted the way it did, and that I had never heard about it. So I started to read and to research. It wasn't until later that I started to feel a real sadness and a real drive to create something expressive around this tragedy."

Robert Camina, whose first film was the award-winning Raid of the Rainbow Lounge, felt that way too, so he raised money for Upstairs Inferno with the help of a Kickstarter campaign and began the emotional task of talking to survivors, families of victims, historians, local politicians, and other experts. He got a boost by the fire's 40th anniversary memorial services, held in the city last June. So did Anderson, who spent six years on his documentary; Delery, whose book is eagerly awaited; and Self, the man behind the musical Upstairs, which was perhaps the most controversial of all the recent related projects.

Telling this story, rather memorializing this story of the worst mass killing of gay people in the U.S., had to be told through theater, says Self, who collaborated with director Zachary McCallum (who directed both the February San Francisco Bay Area workshop and the New Orleans premiere in June).

At right: Scenes from the musical tragedy Upstairs, which opened to rave reviews, even though many in New Orleans had concerns about the tragedy being turned into musical theater.

At right: Scenes from the musical tragedy Upstairs, which opened to rave reviews, even though many in New Orleans had concerns about the tragedy being turned into musical theater.

"Theater has a separate function that has to do with activism, recreation, and catharsis," he says. "Theater incarnates. It brings ideas into a very present, fleshy, intimate reality, without the distance of film or the analysis of history. For that reason, this project, premiering as it did on the 40th anniversary of the fire, became equal parts theater, community activism, and memorial. Some people said they felt like they were watching history. Others said they felt like they could finally say goodbye. We had the children of victims there. The friends of victims. We had survivors there, in that small venue, watching us re-create the night of the fire. It was humbling and frightening and deeply rewarding. And it's something only theater can do."

Many locals were angry to hear of Self's musical, many expecting some exploitive light theater piece like The Sound of Music. Once they saw the almost-operatic musical tragedy he created, people changed their minds.

"People contacted me with blunt questions about why I want to bring this old tragedy up at all," he says. "In the face of such a stunning, graphic, and potentially politically outrageous loss of life, I think there is an understandable impulse to forget it and move along. To people with this impulse, any art or scholarship around the fire is seen as exploitative or morbid or insensitive. One longtime member of the gay community in New Orleans swore he'd be there opening night and would stand up and stop the show as soon as it was disrespectful. I'm told he left in tears at the end."

Perhaps that's because "Upstairs isn't like most musical theater; it's a requiem with dialogue. It's a passion play set to music, and the music is organic to the setting." After all, he says, New Orleans is one of the most musical cities in the world, and the UpStairs Lounge was a cabaret bar -- plus one of the victims was a classical pianist who had been featured on national television and another was a local jazz pianist.

THE PROBLEM WITH RECOVERYBouncing back from a tragedy like this isn't easy for anyone. Although most of the victims were identified (four remain unnamed), some victims were never claimed by family members, generally out of shame and stigma, and buried in unmarked pauper's graves. Some of the survivors had repercussions in their lives after local newspapers published their names, essentially outing them to their families and employers. According to

Time magazine's Elizabeth Dias, one man, who later died of his injuries, was fired from his teaching job while he was still in the hospital, and others "had to go to work on Monday morning" -- the very next day -- as if "nothing happened."

At right: Mourners gathered outside the bar for the 40th anniversary memorial last June.

At right: Mourners gathered outside the bar for the 40th anniversary memorial last June.

Some say police bungled the investigation, or worse, didn't bother to investigate much because it was a "queer bar." Local officials disagree; at one point 50 officers were assigned to the case. Either way, a suspect was never caught or punished, though Rodger Nunez, that hustler who was booted that night, drunkenly confessed to friends on more than one occasion that he started the fire. There was even some circumstantial evidence that pointed in his direction.

As he was booted from the building, Nunez shouted a threat, though the exact wording has been reported different ways over the years, so knowing exactly what he said is difficult to ascertain. This year Time magazine reported that he said he would "burn this place down," while the local newspaper, the Times-Picayune, reported that he said, "I'll come back and burn you all out." Either way, most agree that Nunez had threatened the patrons and bartender Rasmussen, who fingered Nunez from his hospital bed the next day.

Police knew early on this was a case of arson, started with a small can of lighter fluid that was probably purchased from the nearby Walgreens moments before the fireball shot into the building. The Walgreens clerk could tell police the buyer was a gay man who seemed distraught, but couldn't identify him clearly. Nunez's alcohol abuse continued unabated after the fire. When he was drunk he would talk about the killing, the fire. Sober he'd deny it. A year after the UpStairs Lounge fire claimed 32 lives and ruined countless others, it claimed yet one more: Rodger Nunez killed himself.

Camina says that from the people he's interviewed, it's clear that some gay people "were embarrassed or ashamed" in the days after the fire. "The fire did not launch a revolution, and the little activism that was spawned from the tragedy fizzled out very quickly. Also, you have families that didn't claim their dead children. As a collective community, that is shameful and embarrassing. You also have a prime suspect who is a member of the LGBT community. Evidence points to the fact that this horrific crime was committed by one of our own. Furthermore, there isn't any official closure. Police weren't able to charge anyone with the crime. While the evidence points to Nunez committing the crime, there is no justice. Lastly, I think few people know about the story because it is still too painful for people to talk about."

Indeed, Duane Mitchell, now a grown man in Rainsville, Ark., who calls his dad a "hero" for going back in to save his partner, says the fact that no one has ever been charged with the killing makes this a tragedy without closure for many of the families of the dead -- and no doubt for the few living survivors.

At left: George Mitchell dressed up as Queen Victoria, in happier times.

At left: George Mitchell dressed up as Queen Victoria, in happier times.

"It was very emotional, sitting across from this gentleman who experienced such immense trauma as a child," says Anderson, who showed Duane photos of his father he'd never seen before, including one of him dressed as Queen Victoria.

"Duane called his dad a hero -- that was so poignant to me," Anderson says. "A son acknowledging his father's last selfless act, in a time when too many people turned their backs and walked away."

If the lovers entwined, dying in a blaze together doesn't gut-punch you, it's the stories of the victims' children, many who didn't know what had happened to their fathers until recently. TinaMarie Matyi lost her dad, Buddy (George) Stephen Matyi, that affable and handsome piano player.

"I just recently found out the whole truth about what happened to my own dad," Matyi wrote on Back2Stonewall. "He was asked to play by one of his friends. It really upset me on how someone can kill someone. My dad was trying to provide for his family and be a part of his friends. Was he gay? I don't know and if he was I really don't care. This jerk took away my dad. My dad had two sons and myself. We have lost our dad, my grandmother lost a son, and my mom lost her husband. I pray every night that nothing like this happens to my son because he is gay and I could not be prouder."

Thanks to the anniversary media coverage, people like Matyi are connecting with others like Mary Mihalyfi, who lost her favorite uncle, Glenn R. Green, in the fire. Skylar Fein's haunting art installation, Remember the Upstairs Lounge, which was acquired by the New Orleans Museum of Art this year, riveted people with a 90-piece exhibition that included a reproduction of the bar and faux artifacts, along with photographs and video about the tragedy. It helped others grieve in public, something no one could do in 1973.

An episode of Ghost Hunters on Syfy even tried to connect the living with the dead by visiting the bar, now named Jimini Lounge. All the recent media attention has combined with work by New Orleans's LGBT community, which hosted an anniversary memorial in June, to increase the visibility of the fire far beyond the recognition it mever got in 1973.

The stigma and horror of it all, says Self, surely held folks back in 1973.

"Shame cuts both ways, and shame is an important theme throughout the play," Self says. "Were the unidentified victims a lesson for gays and their families on the perils of the closet? Or did the reaction of some of the more hateful people in the community only serve to make people feel even more ashamed? The community as a whole was victimized and abused by the fire and its aftermath. The emotion surrounding the fire, these 40 years later, is a testament to the fire's impact on the city."

Even each of these men -- Self, Anderson, Camina -- who have worked on the projects surrounding the UpStairs Lounge massacre have been profoundly affected, with a sort of creative PTSD that may never go away.

"I think a lingering issue that is rarely talked about is the mystery surrounding the unknown victims," Camina says. "These men went missing and no one claimed them? I can't wrap my head around it. It's unfathomable. I grieve for the unidentified victims of the fire. I don't believe they have found peace yet. I am shocked and sickened that the families never claimed them and that their bodies were dumped into a pauper's grave."

At left: Upstairs writer-composer Wayne Self says the story of the fire will never leave him.

At left: Upstairs writer-composer Wayne Self says the story of the fire will never leave him.

Looking into people's eyes as they experience pain and anguish did not come easy, Camina says. "When I stood outside the bar on the morning of June 25, I stared at the building and tried to imagine what it must have been like 40 years ago, the morning after the fire. I imagined the smell of soot and death in air and the suffocating amount of grief. I got chills. When I returned to New Orleans in September, the site was no less chilling. My tour through the bar was equally as emotional. I stood at the second-story window and peered down the fire escape to the pavement below. This was one of the last sights people saw before they died. I stood next to the infamous window: the one which Reverend Larson got wedged in and was burned alive. I was standing in the footprints where these people died. It was heart-wrenching. We walked through the rear exit door where Buddy led the few survivors to the roof. We were walking in their footsteps. It was surreal. You can't help but cry."

For Anderson, six years of his life devoted to documenting this story, the tragedy still lingers. "There was one photo of a dead patron deceased underneath a couple of barstools, with his T-shirt pulled up, showing his stomach," he recalls. "He probably was using the shirt to cover his mouth from the smoke. The look on his soot-covered face was awful. It's a disturbing photo, one that can't be erased from my memory."

Making the musical Upstairs was a challenge unlike anything he's ever faced says Self, a GLAAD media spokesman as well as a playwright and composer: "I'm still affected by it, to the extent that I'm not yet working on anything else. In order to treat the topic fairly and sensitively, I had to face the victims head-on and try to know them as best as I could."

Making the musical Upstairs was a challenge unlike anything he's ever faced says Self, a GLAAD media spokesman as well as a playwright and composer: "I'm still affected by it, to the extent that I'm not yet working on anything else. In order to treat the topic fairly and sensitively, I had to face the victims head-on and try to know them as best as I could."

At right: Varla Jean Merman (right) and Charles Romaine in Upstairs, the musical.

His play doesn't trade in the morbidity of the night, as would be so easy to do, but the people, the victims, the horror is there in the subtext. As with Camina, his ride is just beginning. The musical will be playing in conjunction with Acadiana Pride in Lafayette, La., next June, the city's inaugural Pride festival.

He's in talks with various theaters around the country to have them produce and present the play and he's fundraising to put on a national tour. It's the love of the people of New Orleans, their desire to see this story come alive, that has kept him going.

"It's not often that you get to work on a project that has such political, social, and emotional resonance with people," he says. "This is the sort of work that a lot of us got into theatre to do, but rarely get to do. It fulfills that promise, and allows us to share something with a whole community."

The show focuses tightly on the night of the fire and its relatively immediate aftermath. The themes are broad and relevant to the LGBT experience today: pride, shame, alienation, acceptance, forgiveness, rage, religion, family, survival, and death. The fire and its victims speak to us today because their experience presages our own experience with family struggles, with spiritual struggles, with AIDS, with a long, slow march from shame to acceptance to public celebration of our relationships -- a march that saw a lot of losses along the way. Yes, the mayors and religious leaders would comment today, and nearly all of those comments would be supportive and kind. And we owe it to those who didn't live in these conditions to remember them and celebrate their contributions.

Camina looks forward to 2014, but knows he'll never stop thinking about 1973.

"The story and the victims will always be a part of me," he says. "These people are more than statistics and more than plot points. The people that were there were sons, dads, brothers, uncles, moms, sisters. I will never leave them behind. I want to do all I can to help educate future leaders and find a way to turn this tragedy into teachable moments. We should never allow ourselves to forget them -- again."

Editor's note: The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Religious Archives Network has a comprehensive digital exhibit on the UpStairs Lounge fire with personal essays, old photos and media clippings, and excerpts from Townsend's compendium.

Duane says he and Steve watched that movie seven times and Dad just never came back. Finally, George's landlady picked the boys up that night, and the next day a neighbor took them to the airport to fly home to Alabama, all the while not telling them the ugly truth of why Dad never returned.

Duane says he and Steve watched that movie seven times and Dad just never came back. Finally, George's landlady picked the boys up that night, and the next day a neighbor took them to the airport to fly home to Alabama, all the while not telling them the ugly truth of why Dad never returned. At right: Pianist George Matyi wasn't a regular performer at the UpStairs Lounge, but the night of the fire he took the gig as a favor to a friend. He left behind a daughter and two sons who only recently learned the truth of his death.

At right: Pianist George Matyi wasn't a regular performer at the UpStairs Lounge, but the night of the fire he took the gig as a favor to a friend. He left behind a daughter and two sons who only recently learned the truth of his death. At left: Bartender Buddy Rasmussen (right, with a friend) led 20 people to safety but inadvertently locked the door behind them, closing off the only escape route.

At left: Bartender Buddy Rasmussen (right, with a friend) led 20 people to safety but inadvertently locked the door behind them, closing off the only escape route.

At left: Duane Mitchell (left) looks at photos of his dad, George, with filmmaker Royd Anderson. Duane was 11 years old at the time of George's death.

At left: Duane Mitchell (left) looks at photos of his dad, George, with filmmaker Royd Anderson. Duane was 11 years old at the time of George's death. At right: MCC pastor Bill Larson, trapped in the window bars, where he remained for hours during the investigation. He was promoted to reverend posthumously.

At right: MCC pastor Bill Larson, trapped in the window bars, where he remained for hours during the investigation. He was promoted to reverend posthumously.

At left: Filmmaker Robert L. Camina in front of the plaque memorializing the UpStairs Lounge massacre.

At left: Filmmaker Robert L. Camina in front of the plaque memorializing the UpStairs Lounge massacre. At left: Author Johnny Townsend (left, with filmmaker Royd Anderson) wrote about the fire 20 years ago. Because of the age of many survivors, Townsend is thought to have been the last person to really record many of the survivors' stories.

At left: Author Johnny Townsend (left, with filmmaker Royd Anderson) wrote about the fire 20 years ago. Because of the age of many survivors, Townsend is thought to have been the last person to really record many of the survivors' stories. At right: Scenes from the musical tragedy Upstairs, which opened to rave reviews, even though many in New Orleans had concerns about the tragedy being turned into musical theater.

At right: Scenes from the musical tragedy Upstairs, which opened to rave reviews, even though many in New Orleans had concerns about the tragedy being turned into musical theater. At right: Mourners gathered outside the bar for the 40th anniversary memorial last June.

At right: Mourners gathered outside the bar for the 40th anniversary memorial last June. At left: George Mitchell dressed up as Queen Victoria, in happier times.

At left: George Mitchell dressed up as Queen Victoria, in happier times. At left: Upstairs writer-composer Wayne Self says the story of the fire will never leave him.

At left: Upstairs writer-composer Wayne Self says the story of the fire will never leave him.  Making the musical Upstairs was a challenge unlike anything he's ever faced says Self, a GLAAD media spokesman as well as a playwright and composer: "I'm still affected by it, to the extent that I'm not yet working on anything else. In order to treat the topic fairly and sensitively, I had to face the victims head-on and try to know them as best as I could."

Making the musical Upstairs was a challenge unlike anything he's ever faced says Self, a GLAAD media spokesman as well as a playwright and composer: "I'm still affected by it, to the extent that I'm not yet working on anything else. In order to treat the topic fairly and sensitively, I had to face the victims head-on and try to know them as best as I could."

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella