Marijane Meaker isn't a household name, but she should be. A literary pioneer many times over, she wrote the 1952 novel Spring Fire, one of the first lesbian "pulps," giving thousands of Americans their first glimpse of a sexually compatible same-sex couple, even if the rules of the genre required that the relationship end badly. Her books about lesbian life in New York City, which appeared between 1955 and 1972, were indispensable guides to a hidden world. And beginning in the 1970s, she was one of the first authors to write for young adults, often telling stories of underdogs and "others," including gay and lesbian teenagers. Over a career spanning 65 years, more than 60 books, and millions of copies sold, she has consistently, if not exclusively, published groundbreaking work on queer topics. Best of all, at 88, she is still going strong and is currently at work on her autobiography.

Meaker's relative obscurity is partly due to her passion for pseudonyms -- she has published books under at least six pen names, and short stories and articles under many more. Her first success came just after college when she moved to New York and worked as a file clerk at a publishing house. She bonded with her boss, Dick Carroll, mostly over a shared love of Scotch. She would head to his office at the end of the workday, knowing he'd be happy to drink with her -- and during one of those sessions she convinced him to sign her up to write a novel based on her lesbian experiences at boarding school.

Carroll took a chance on Meaker, but he insisted on two changes to the real story: First, the girls must be older, and second, homosexuality couldn't be presented in a positive light. The latter requirement wasn't just a matter of maintaining mid-century mores; at the time, postal regulations prohibited the sending of gay material through the U.S. Mail. Meaker explained: "When you shipped a carton of books, they went through them, and if any books in the carton were gay, the whole lot would be seized. So you had to censor yourself, because you didn't want other authors to be punished for something you wrote." The best way to keep the authorities at bay was to follow the instruction Carroll gave his young drinking buddy: "No happy endings."

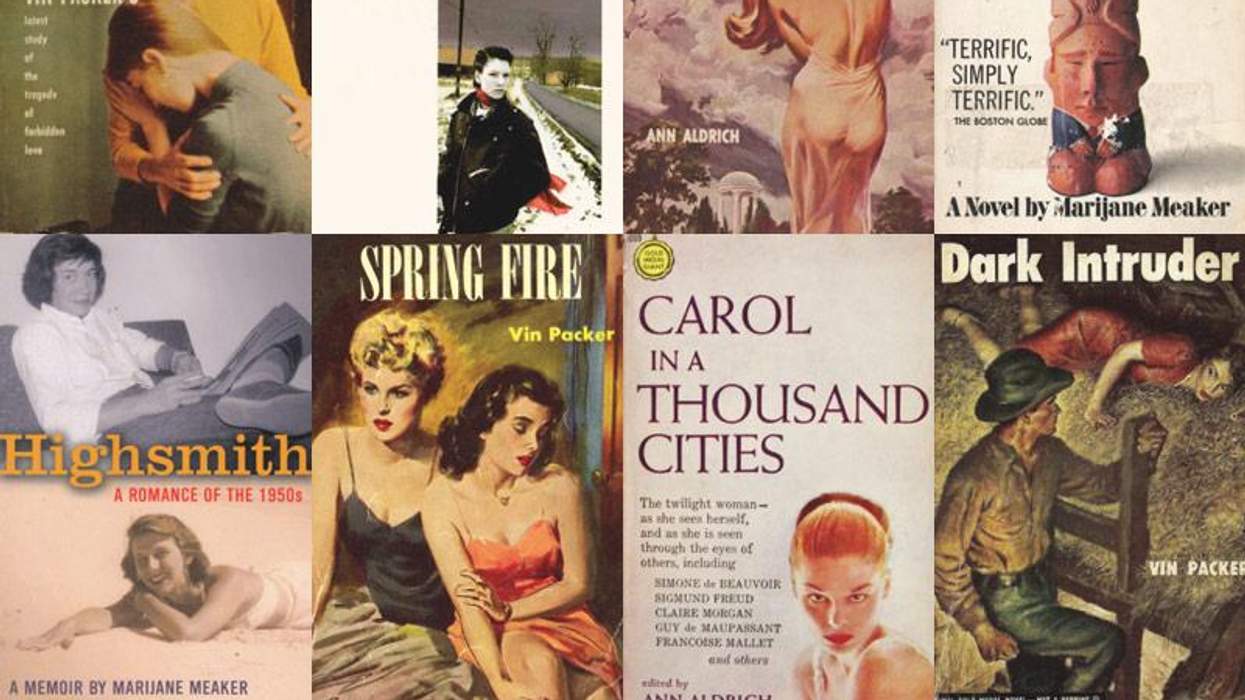

The resulting novel, Spring Fire, attributed to Vin Packer -- which later became Meaker's pseudonym for mystery and suspense novels -- tells the story of two Tri Epsilon sorority sisters at Cranston University. Mitch, a boyish freshman, and Leda, her beautiful bisexual roommate, fall in love and find happiness together, until Leda breaks down and is committed to an insane asylum. In her foreword to the 2004 reissue, Meaker acknowledges that some of the prose embarrasses her now, as does the gloomy ending. But as critics have pointed out, contemporary readers were skilled at ignoring the pulps' negative messages. The women who bought these paperbacks for 25 cents at drugstores and railway stations would, as Susan Stryker wrote in Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions From the Golden Age of the Paperback, "tease out subtextual sympathies in books that were often overtly homophobic and misogynistic."

Spring Fire sold 1,463,917 copies in 1952 alone, an astounding number that shocked -- and thrilled -- Carroll and his bosses at Fawcett. He offered to double her penny-per-copy royalty rate if she would write another lesbian novel, but she refused. "I didn't want to be known as a queer writer. I was trying to write a good story rather than a lurid story," she told me recently. But when heartfelt letters started to pour in from women all over the country -- along with a few dirty pictures sent by men -- she decided to create a new pseudonym, Ann Aldrich, and pen a nonfiction guide to lesbian life. "The letters made me realize how needy people were for information," she says.

The five Ann Aldrich books -- 1955's We Walk Alone; 1958's We, Too, Must Love; 1960's Carol in a Thousand Cities; 1963's We Two Won't Last; and 1972's Take a Lesbian to Lunch -- were written from the point of view of an opinionated gay girl about New York City. Aldrich dished on the bohemian lesbians of Greenwich Village, the chic uptown ladies who looked down on the trouser-wearing types below 14th Street, and the dating habits of them all. "Hands-Around, the most often played game among Manhattan Lesbians," she wrote in We, Too, Must Love, "keeps the jewelers busy engraving new sentiments on watches, bracelets, coins and rings; keeps landlords busy changing the nameplates in the vestibules of apartment buildings; keeps the post office busy with change-of-address cards; the phone company busy with new listings, and the moving men busy moving one girl's belongings out of one apartment and into another."

The books were wildly popular -- Meaker says the first four had initial print runs of 400,000. Still, Aldrich's frank depictions of lesbian relationships -- and her rather harsh view of butch dykes, whom she sometimes referred to as "transvestites" -- annoyed the activists in the Daughters of Bilitis, who feuded with Aldrich in the pages of the organization's newsletter, The Ladder. Aldrich responded by making fun of The Ladder in her books. Despite their enmity, being mentioned in such popular volumes was probably the best publicity the Daughters of Bilitis ever received.

One of Aldrich's detractors at The Ladder declared that her books "reveal...superlative early training in Writing to Sell." That accusation, meant as an insult, was nevertheless an astute observation. As a self-supporting writer, Meaker was supremely sensitive to publishing trends. When publishers started to target "young adults" in the early 1970s, M.E. Kerr -- yet another pen name of Meaker's, perhaps her most successful -- was an early exponent. Once again, she enjoyed success with her first attempt at a genre: School Library Journal named 1972's Dinky Hocker Shoots Smack, about an overweight 14-year-old fighting for her do-gooder mother's attention, one of the 20th century's 100 most significant books for children and young adults. Twenty-four other YA titles followed, including 1986's Night Kites, about a 17-year-old boy dealing with his gay brother's AIDS diagnosis; 1994's Deliver Us From Evie, a sweet story about a butch farm girl who leaves her rural home so she can live openly with her girlfriend in Manhattan; and 1997's "Hello," I Lied, about a young man's coming out.

Thanks to ebooks, a renewed interest in early lesbian writing, and libraries' long-term appreciation for quality YA literature, Meaker's work is relatively easy to track down. There's a potato-chip quality to her books -- once you read one, you immediately crave another. If you're not familiar with her work, start with two books published under her own name. Highsmith: A Romance of the 1950s, a memoir about Meaker's relationship with novelist Patricia Highsmith, is a wonderfully gossipy but refreshingly clear-eyed account of a love affair destroyed by Meaker's jealousy and Highsmith's misanthropy.

My favorite, though, is Shockproof Sydney Skate, a hilarious comic novel about a teenage boy who has broken the code his mother uses when gossiping with members of her lesbian circle. When the book first appeared in 1972, the story of a woman raising a son who is odd but fiercely intelligent, with the help of girlfriends, exes, and the proprietor of a lesbian watering hole, was considered radical and groundbreaking. What else would you expect from Marijane Meaker?

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes