It had only been two days since a gunman opened fire in Orlando's Pulse nightclub, killing 49 people and wounding 53, when CNN anchor Anderson Cooper grilled Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi about whether she could really call herself a "champion of the gay community" after her dogged opposition to marriage equality.

In the tense interview conducted outside Orlando Regional Medical Center June 14, Cooper plainly told Bondi that "many gay and lesbian people" he'd spoken with the day before viewed her promise to defend the LGBT community as "hypocritical." As the attorney general balked, Cooper repeatedly stated that he was simply repeating questions LGBT Floridians had asked him to pass on to the state's top lawyer.

But Bondi wasn't convinced, claiming the next day that the interview had been deceptively edited, and that she'd been brought on the show under false pretenses. Cooper fired back, saying the attorney general was well aware of the intention of the interview, and adding that he remained respectful before, during, and after the interview. It was also fair, he added, for a reporter to ask an elected official about their apparent shift in positions, since, as Cooper said in the initial interview, he never heard Bondi speak about LGBT people "in a positive way" until after the massacre at the Orlando LGBT club.

Some conservative pundits were quick to dismiss Cooper as unprofessional for letting his so-called personal agenda seep into his reporting. While lauding Cooper as a "generally fair" journalist, Fox News media critic Howard Kurtz suggested June 19 that Cooper had crossed a line into activism.

On his Media Buzz program that day, Kurtz asked, "Do gay journalists feel a special anguish over the senseless slaughter of 49 mostly gay Americans?" He also mentioned Cooper's emotional reading of the names of each of the victims killed, which opened Cooper's show, AC 360, the prior Monday.

Kurtz's guest, Fox News contributor Guy Benson, denounced Cooper's questions for Bondi as "browbeating her for political thought crimes in her past."

Although Kurtz's question about the "special anguish" LGBT reporters feel over the worst anti-LGBT hate crime in American history was likely facetious, several out journalists who were on the ground in the week after the Pulse massacre tell The Advocate they did, indeed, feel a personal connection to the story they were covering.

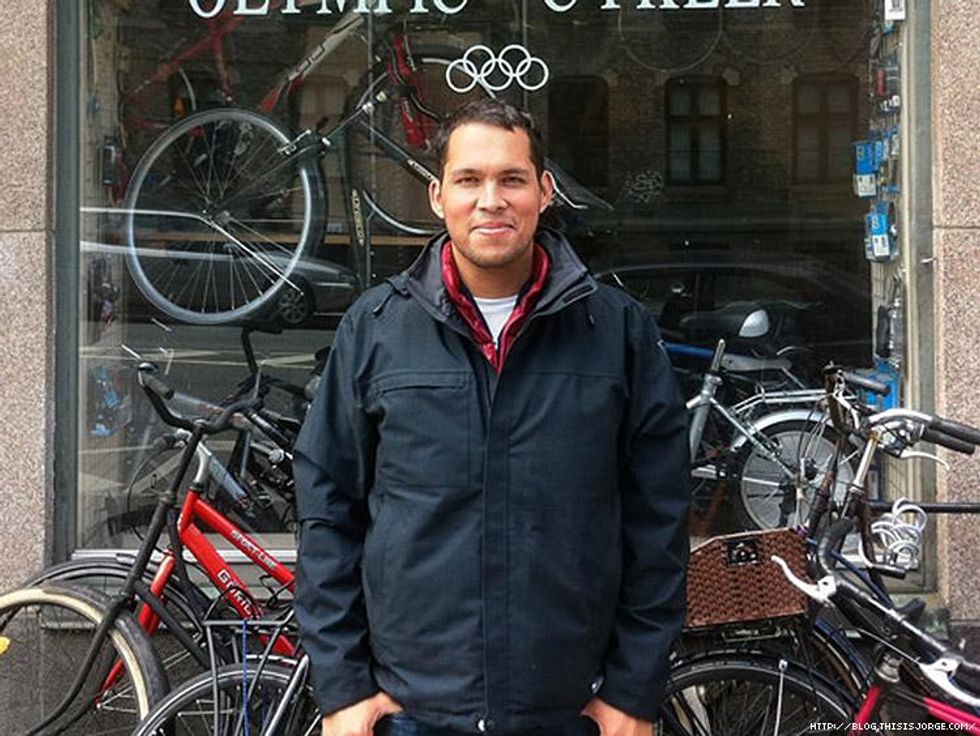

"As a gay Latino man, I knew that I could find stories that other people wouldn't be able to get," says Jorge Rivas of Fusion (pictured above), who landed in Orlando almost exactly 24 hours after the shooting. "And so I felt a responsibility to look for those stories that no one else would find."

Rivas says the tragedy was difficult for him to wrap his head around, especially once he learned that the shooter had targeted the LGBT club's popular Latin night, in a city with a growing Latino and immigrant population.

"If I'm a gay Latino man, I think that is an advantage when I'm covering gay Latino men and the LGBT community," he continues. "In this case, for example, I thought about undocumented immigrants who were at Pulse, and I used [their experience] as a way to talk about the resources that were available to all victims and how people access them and what resources were not available to undocumented individuals."

Once he arrived in Orlando, Rivas saw international broadcast media swarming the scene of the crime, all jockeying for the best live shot. As witnesses and survivors slowly began to engage with media in the days after the shooting, Rivas says, he witnessed reporters from around the world firing aggressive, nonstop questions at people who had just experienced severe trauma. Although Rivas is primarily a print journalist, he does work with Fusion's cable broadcast channel and daily website, so he has a keen understanding of the challenges involved in producing brief but comprehensive segments to be broadcast around the globe.

"Honestly, watching journalists aggressively interview victims that lived through Pulse, I think that's a life lesson for me," says Rivas. "Regardless of who I'm covering -- whether it's LGBT people or not. And I think the reason why I was sent to Orlando was also just because of the sensibilities that I have, and that I live with in my life."

He continues:

"When I approach someone, I introduce myself, and I tell them who I am, who I work for, and what type of story I'm working on and who our audience is, because I think that, as journalists, our job is to make the subjects in these types of stories comfortable. Because if the subject is comfortable, they might volunteer the information that the journalists were aggressively pursuing. ... I think that if everyone's on the same page, then the journalists should be able to get to those stories that they're looking for. But I think there's a respectful way of getting there."

"If anything, I think Orlando just made me more critical of how people make news," Rivas concludes. "And how they deliver news."

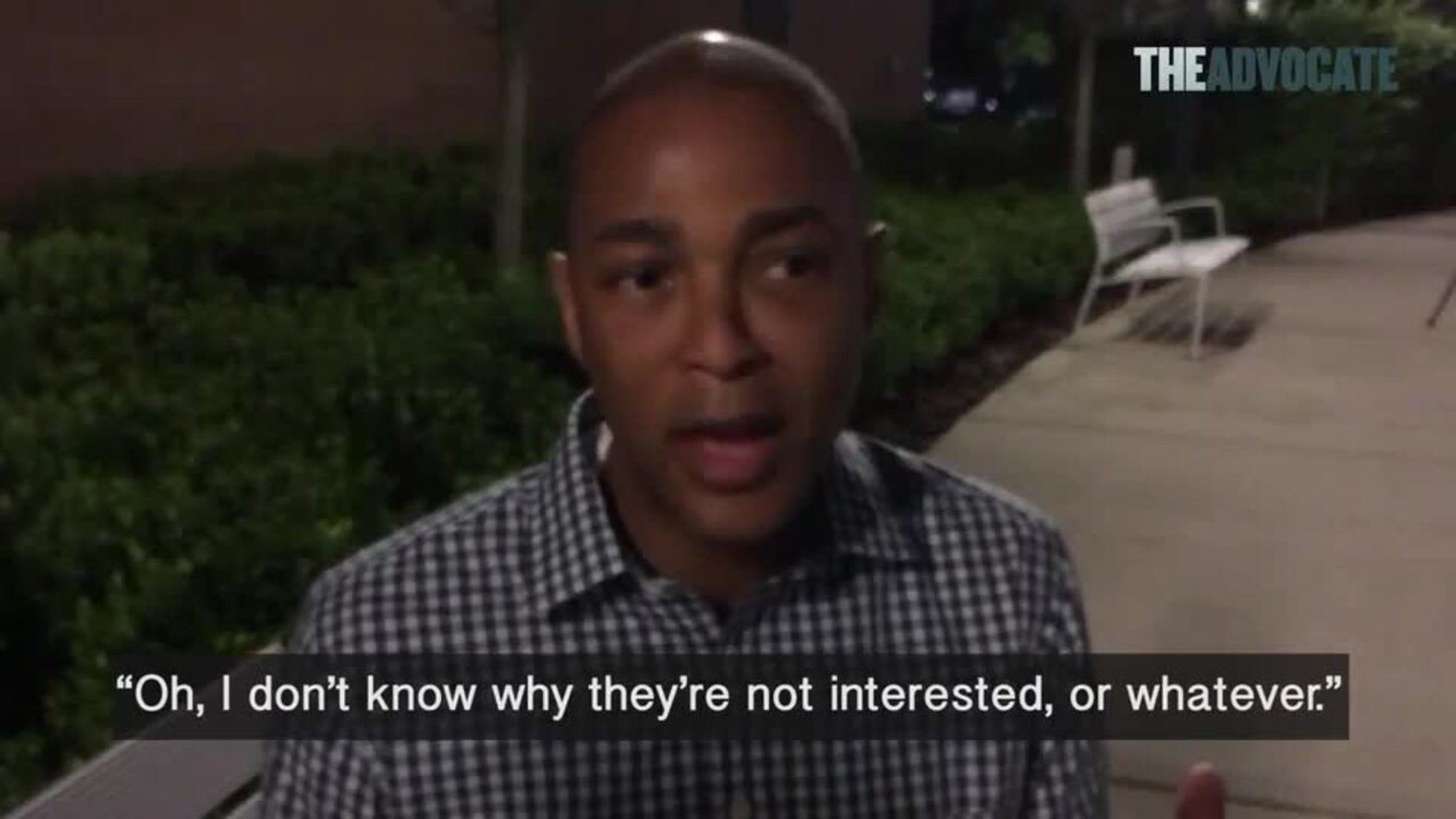

Don Lemon, anchor of CNN Tonight and also a gay man of color, struggled to keep his emotions in check during on-air interviews in Orlando as well. Although he is a seasoned reporter with years of experience reporting on the ground in the wake of crises and tragedies, even he had to set aside time to compose himself.

"I think part of my job is to separate myself as much as possible, so that I am here to tell the story; that I am the vessel to tell the story," he says. "Which is why, when I need a mental health couple of hours, I take it. Because if I'm no good, that's no good for the audience, and that's no good for the people who are counting on me. But I'm human. And so, you become emotional, and you don't know when it's going to happen. You become emotional sometimes just talking about the victims."

Some anchors, however, were able to keep their distance from the emotional impact of the shooting. Thomas Roberts (pictured below), who hosts MSNBC Live, says he's generally an emotional person, but that the Pulse massacre didn't affect him more -- or less -- than the other tragedies he's covered.

"During any one of these events, when we have a mass shooting, it's always emotionally taxing, and surreal, and you can't believe you are on the scene of another one so quickly," he says in a phone interview back in New York City. "I can honestly say that I have felt a deep compassion and empathy, whether it's for the folks that I met in Paris, during the terrorist attack there, or the families in San Bernardino, or the families from Roseburg [Ore.] at the community college. I must admit, it never gets any easier having these conversations with these family members."

But Roberts does acknowledge that his identity as a gay man facilitated some of his connections in Orlando. He was generally connected to his sources by a single degree of separation, Roberts says, because he knew other LGBT people in the Orlando area who knew victims or survivors.

"I don't think I've ever had that type of connectivity on a mass shooting," he says. "And I don't want it again. The ease with which I was able to connect and find people and get information, because so many of the people that I know in that city were there in that club and were able to put me in contact either with people who were in attendance or knew someone firsthand who was in attendance, [was striking]."

Meredith Talusan (pictured above), a staff writer at BuzzFeed and an out queer trans person of color who uses the gender-neutral pronouns they/them, agrees that one's identity within a marginalized group can open doors not available to more mainstream outlets. Talusan, who writes mostly long-form pieces for the viral news site, says they were able to take a more hands-off approach to finding sources, sometimes sitting alone "on the sidelines" of a memorial or news conference.

"In a lot of situations, people have approached me, and said, 'Are you OK?' or like, 'Why are you alone?'" Talusan explains. "And then I would respond, I would say, well, I'm a journalist and I'm writing about this. And [then I would] express my ambivalence about this idea of swooping into a city that I don't know at all -- it's my first time in Orlando. And everybody, to the person, has been incredibly generous. Nobody has said no to me."

"I think that it's important for us, as journalists, to always be ethical," adds Talusan. "It's important for us to disclose our relationships. It's important for us, if we're operating in a context where we're supposed to write about the news in a distanced, dispassionate way, that we maintain that. And that we maintain that type of balance. But it's also really important that, if we do have a really strong opinion, that we express it. And that we incorporate it into the stories that we tell."

Talusan acknowledges that the ever-shifting field of digital journalism and social media has, in many ways, changed the rules of the game for journalists, who were once thought to be a shining beacon of impartiality.

"I think that it is important to live with tensions of your position," says Talusan. "And I think that, in a lot of ways, it's a holdover -- this idea of pure journalistic objectivity, is a holdover from a time when there is an assumed ideal journalist. And that ideal journalist is presumed to be neutral. And neutrality, historically, in our country has been very much associated with majority positions of whiteness and maleness. And so I do think that, yeah, being here makes me really aware of the value of my position, and that I don't have anything to apologize for, for having feelings, for having a perspective, as long as I handle that perspective responsibly."

Fusion's Rivas agrees. "I think there's this archaic idea that sociologists and historians and anthropologists and journalists have to separate themselves from the story," he says. "I don't see why I should detach myself from this story, when my sensibilities can make this story stronger."

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered