Could a seemingly obscure Supreme Court ruling from 37 years ago prove the undoing of the effort to overturn California's Prop. 8 and establish a federal right to same-sex marriage?

June 20 2009 12:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Could a seemingly obscure Supreme Court ruling from 37 years ago prove the undoing of the effort to overturn California's Prop. 8 and establish a federal right to same-sex marriage?

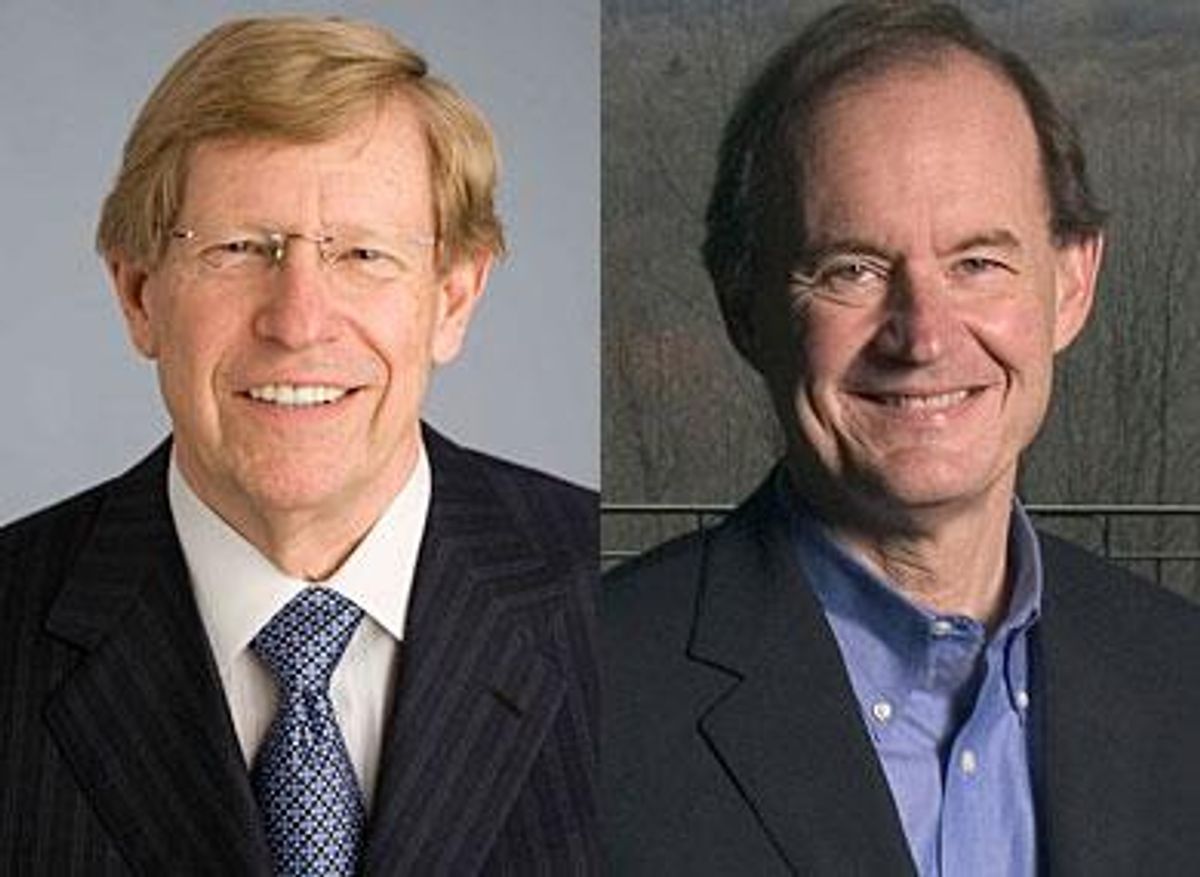

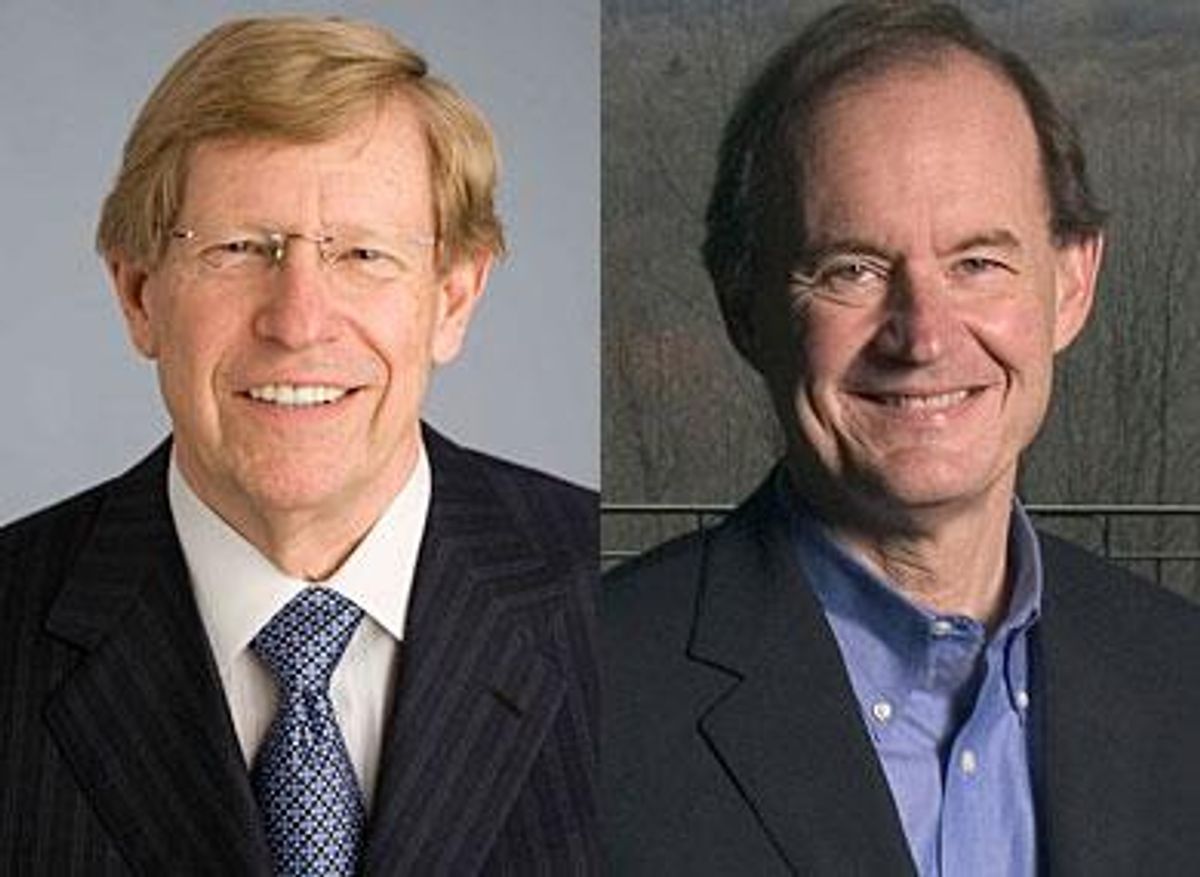

As all sides gear up to do battle over the Prop. 8 suit filed in the San Francisco district court last month by superstar lawyers Ted Olson and David Boies, constitutional experts sympathetic to the marriage equality cause are expressing deep concern over the 1972 case known as Baker v. Nelson and its potential to scupper every last argument about equal protection and due process under the U.S. Constitution.

Here's why.

Baker v. Nelson was a very early same-sex marriage case pitting two gay student activists from the University of Minnesota against the clerk of the county court in Minneapolis. The activists wanted to get married and applied for a license. The clerk said no, on the grounds that they were two men, not a man and a woman. The case went to court, and the activists lost at every stage, all the way up to the Minnesota supreme court and beyond. The U.S. Supreme Court, for its part, refused to hear the case, citing a lack of a "substantial federal question."

So far, unsurprising, given the times.

The problem stems from the fact that, at the time, the Supreme Court enjoyed something known as "mandatory appellate jurisdiction." In plain English, this meant that once the Supreme Court ruled on a legal matter, only the Supreme Court had the power to reverse the decision. The lower courts' hands were tied, and if any subsequent case came their way they had no choice but to say they had no power in the matter.

A lot of things have changed since 1972, not least the fact that the Supreme Court lost its power of mandatory appellate jurisdiction in the mid '80s. It is also not at all clear whether the jurisdiction in the Baker case ever extended to all same-sex marriage cases, or whether it applied only to Minnesota and the particular circumstances considered at the time.

No matter. Baker v. Nelson is now being cited as a reason why the district court in San Francisco should dismiss the Boies-Olson suit -- and any other similar federal suit -- out of hand. What makes it dangerous is that a federal judge nervous about jumping into the same-sex marriage controversy might just reach out for it gratefully as an excuse not to commit one way or the other.

That, in turn, means the Boies-Olson team might not win the lower court victory they want to maximize their chances of being heard, and then winning, in the U.S. Supreme Court.

"As a matter of jurisprudence, it seems an enormous stretch," said Mike Dorf, a constitutional law professor at Cornell. "But what it does is it allows whoever is going to intervene on behalf of Prop. 8 to tell the court, 'Look, whatever you may think, you don't have the authority to do anything here.'"

Ironically, the Baker v. Nelson case was not first cited by the Alliance Defense Fund or another campaign group hostile to same-sex marriage. It came up in the Obama administration brief filed earlier this month in a federal case filed by a gay couple from Orange County, Calif.

That brief has already caused a furor because of the extraordinary vehemence of its arguments against same-sex marriage. What it says in relation to Baker v. Nelson has received little or no attention outside of legal circles, yet it could be the most damaging part of all.

Here is the key sentence. Citing Baker, the Justice Department writes: "Regardless of whether same-sex marriage is appropriate policy, under current legal precedent there is no constitutional right to it, and that precedent is binding on these parties and this court."

Professor Dorf commented: "The fact that the Obama administration is arguing this only boosts the case for supporters of Prop. 8. And it offers an easy out for a judge who doesn't want to take the heat for deciding this."

For now, the Boies-Olson team is taking a relatively relaxed view of the matter. "The good news is, the assertion is completely wrong," said Ted Boutrous, a partner in Olson's firm of Gibson, Dunn, & Crutcher. "What Baker v. Nelson means is that whatever law was on the books in Minnesota at the time is potentially insulated from review. It would have no binding effect on reviewing Prop. 8."

In a court brief filed yesterday, the Boies-Olson team elaborate this argument further, saying that circumstances in modern-day California are entirely different from 1970s Minnesota, and that the legal environment has changed entirely because of such landmark LGBT rights rulings as Romer v. Evans (a Colorado state discrimination case) and Lawrence v. Texas (which overturned existing state anti-sodomy laws).

"Even if Baker had not been conclusively undermined by the Supreme Court's subsequent decisions in Romer and Lawrence, " the brief says, "it still would not be binding on this court because the Supreme Court's summary dismissals have controlling force only 'on the precise issues presented and necessarily decided' by the Supreme Court."

It remains to be seen whether the optimism of the Boies-Olson team is warranted. Baker v. Nelson has, however, been cited in the past as a reason to stop a same-sex marriage suit in its tracks. In the 2005 Wilson v. Ake case in Florida, two women who had married in Massachusetts went to federal court to argue that their home state's refusal to recognize their union was a violation of their constitutional rights. The district court dismissed their claim, saying that because of Baker it had no power even to hear them.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella