Being a homosexual in

America in 1964 was not easy, and one of the more difficult

places to be one was Washington, D.C. While the nation's

capital has long since become the setting for some of the most

important gay rights battles (and home to a vibrant gay scene),

it was also the site of routine antigay witch hunts. At the

time, gays were officially barred from working in government

and their livelihood depended on the secreting of their

sexuality. Indeed, the mere suspicion of homosexuality could

get a person fired, and the consequences of losing one's job

due to what was then known as a "morals charge" were

long-lasting.

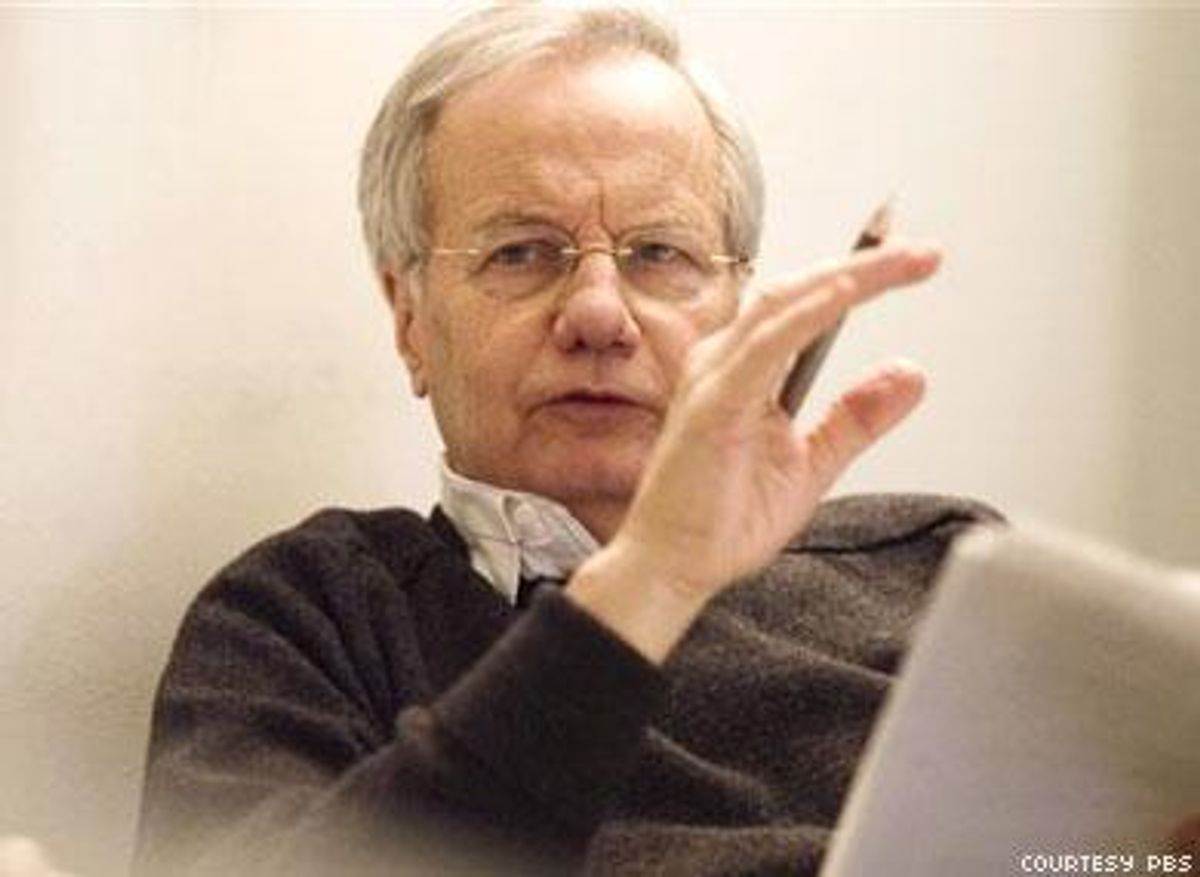

It's in this context

that recent revelations about Bill Moyers are so disturbing.

Before he became the self-righteous scold of the liberal

television commentariat, Moyers served as a special assistant

to Democratic president Lyndon Johnson. This was at the height

of J. Edgar Hoover's reign over the Federal Bureau of

Investigation, during which time the FBI

director spied on a vast array of public and private

citizens in order to gather information for potential

blackmail.

According to documents

obtained last week by

TheWashington Post

through a Freedom of Information Act request, one of these

individuals was former Johnson aide Jack Valenti, later head of

the Motion Picture Association of America. Hoover, according to

the

Post

, was "consumed" by the question of whether Valenti was

gay, and deployed his agents to investigate the man's sex

life.

They turned up

nothing.

Valenti, however, was

not the only White House official to be investigated by the FBI

for suspected homosexuality. In late 1964, just weeks before

the presidential election, senior White House adviser Walter

Jenkins was arrested in a YMCA men's room for performing oral

sex on another man. Under extreme mental duress, Jenkins

checked into a hospital and resigned his position. Moyers

wasted no time in trying to discover how much more potential

trouble the Johnson administration might have with gays in its

midst, and went out of his way to ask Hoover's FBI to

investigate two other administration officials "suspected as

having homosexual tendencies," according to the recently

released documents.

In an e-mail response

to an article written by Slate's Jack Shafer, Moyers complains

about Hoover, but does not bother to address the matter of his

ordering the FBI to snoop on his colleagues.

These revelations once

again remind us that empathy for the dignity of gay people does

not always fall along partisan political lines. Whereas Barry

Goldwater, one of the crucial figures in the birth of the

conservative movement, could have easily exploited the Jenkins

scandal in the presidential campaign, he refused to discuss it.

In his memoir Goldwater wrote, "It was a sad time for Jenkins

and his family. Winning isn't everything. Some things, like

loyalty to friends, or lasting principle, are more

important."

Goldwater, today

remembered by most liberals as a fire-breathing Neanderthal,

later became an outspoken opponent of the ban on gays in the

military.

Contrast Goldwater's

behavior to that of Moyers, who abused his power in office to

hunt down and expose the gays in his midst. (Here it should be

noted that rooting out gays in government wasn't the only dirty

task Moyers conducted while working in the Johnson White House.

He also oversaw the FBI's wiretapping of Martin Luther King and

successfully prevented the civil rights activist from

challenging Mississippi's all-white delegation to the

Democratic National Convention in 1964. "You know you have

only to call on us when a similar situation arises," he

encouraged the FBI agent in charge of the domestic

espionage.)

To be sure, Moyers's

behavior at the time took place within a social milieu far more

repressive than today's. It wasn't until 1973, after all, that

the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from

its list of disorders. Gays were banned from working in the

federal civil service until 1975. And gays were barred from

having security clearances, amazingly, until 1995. That Moyers

engaged in Nixonian dirty tricks with the aim of embarrassing

and ruining the careers of gay people, while despicable, was

something that many officials in his position probably would

have done, given the mores of the era.

But what makes Moyers's

contemptible behavior relevant is that even to this day he has

yet to acknowledge wrongdoing, never mind apologize. That

Moyers has since become a supporter of gay rights is

irrelevant. None of that erases the fact that he used his power

as a senior White House official to pry into the private lives

of his own colleagues.

Today, he has the gall

to excoriate other public figures and lecture the rest of us on

virtue. After leaving government, Moyers became a journalist

and subsequently produced PBS documentaries excoriating Richard

Nixon over Watergate and Ronald Reagan over Iran-Contra. In the

early 1990s, his star was so high and his reputation so

pristine that he publicly considered running for president. His

sanctimony rivals that of the pope.

Given his own history

of snooping into the private lives of American citizens with

the intent to publicly humiliate them, Moyers's latter-day

sermonizing on the evils of the Bush administration and

conservatives in general rings more than a little hollow. And

the fact that he has been getting rich off the public trough

for decades -- earning millions of dollars in production deals

from his documentaries and television programs aired on Public

Broadcasting -- makes a full explanation of his activities in

government service all the more necessary.

Moyers didn't just seek

dirt on his own colleagues but his political enemies as well.

In 1975, then-deputy attorney general Laurence Silberman was

tasked with the job of reviewing a raft of secret files once

belonging to J. Edgar Hoover. Amid "nasty bits of information

on various political figures," Silberman found a letter

drafted by Moyers requesting an FBI investigation of suspected

gays on Goldwater's campaign staff. When the press reported on

this document, Silberman received an angry phone call from

Moyers, who alleged that the report was a CIA forgery. When

Silberman offered to conduct an investigation so as to

exonerate Moyers, the former presidential aide demurred. "I

was very young," Moyers confessed to Silberman. "How will I

explain this to my children?"

It's a good question.

And one that we're still waiting for Bill Moyers to answer.