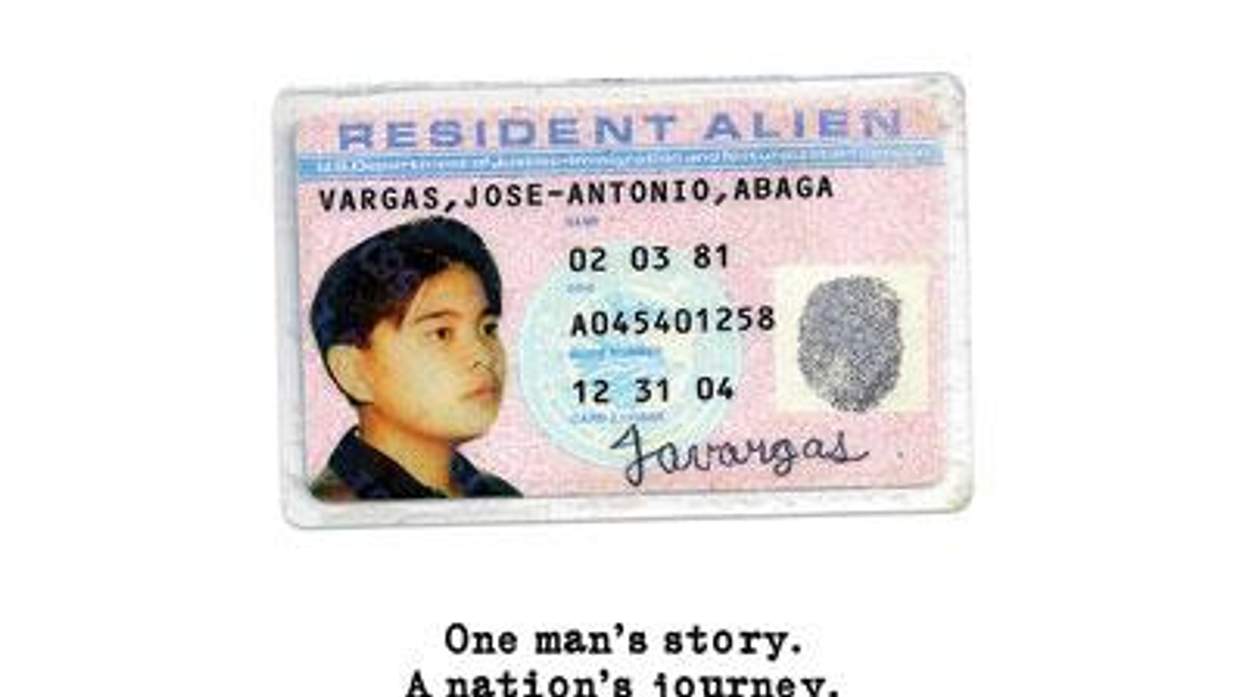

Jose Antonio Vargas spent most of his adult life as a hardworking journalist, keeping his head down, his copy clean, and his immigration status secret. Out as a gay man since he was 18 years old, Vargas attended San Francisco State University on a scholarship, then was hired directly out of school as a staff writer for The Washington Post, where he ultimately won a Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Reporting in 2008 as part of the team that covered the shootings at Virginia Tech in print and online.

"I focused so much on other people so I didn't have to talk about myself," Vargas tells The Advocate.

But that all changed June 22, 2011, when The New York Times' Sunday magazine published a feature he wrote titled "My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant."

"I'm done running," Vargas wrote in the piece, which detailed how his mother sent a 12-year-old Jose on a plane from the Philippines to live with his grandparents in California's Bay Area in 1993, leaving Vargas unaware that he lacked legal documentation to be in the U.S. until he attempted to obtain a driver's license at 16. "I'm exhausted. I don't want that life anymore."

That article introduced the country to Vargas and proved a pivotal turning point in his life, making him the face of the often polarizing issues surrounding immigration and landing him and a group of fellow undocumented immigrants on the cover of Time magazine a year later.

Now Vargas is once again inviting the American public into his life as a way to personalize and illustrate the often abstract, highfalutin discussion of immigration reform. Starting Sunday at 9 p.m. Eastern, CNN will air Vargas's debut in feature filmmaking -- an autobiographical documentary called Documented. It will air again at 11 p.m., then July 5 at the same times, and will ultimately be available on digital platforms as well.

The documentary was filmed over the course of three years, beginning just two months before Vargas came out as undocumented in The New York Times. And while he initially intended the film to be a straightforward documentary of his journey to revealing his immigration status, it quickly became apparent that the film demanded a more personal perspective, delving into old wounds left by decades of separation from his family.

"The film kind of tells you what it needs to be," says Vargas. "It became clear that the story had to be about my mom. So once it made that transition, I had to start asking myself, OK, am I really ready for this?"

Jose Antonio Vargas with his mother in the Philippines. Image courtesy of Apo Anak Productions.

Jose Antonio Vargas with his mother in the Philippines. Image courtesy of Apo Anak Productions.

In fact, Vargas says he didn't particularly plan to address his sexual orientation in his initial imagining of the film. And as it stands, Documented actually positions Vargas's coming out as gay as the "easier" coming out, compared with telling his friends he is undocumented.

That's a realistic depiction, he says. Although he was the first openly gay student at his Mountain View, Calif., high school, when Vargas came out in his junior year, in 1999, he says he was almost universally accepted by his peers.

"When I was 16, and I found out I was undocumented, or 'illegal,' around that same time, because of AOL chat rooms I knew that I was gay," Vargas explains. "So there was a moment in my life, between the ages of 16 and 17, about a year and a half, where I was closeted about being gay and being undocumented. ... And I just couldn't be in the closet about both those things. ... I ended up coming out of the other [closet], because it was just easier [to come out as gay]."

And even though he grew up in admittedly privileged suburban Northern California, Vargas says he still internalized the antigay, anti-immigrant messages that permeated his world.

"When you're a teenager and you know that you're the illegal f****t, you start internalizing what that is," he says. "And there's a kind of hardening that happens."

Documented, he says, is an effort to break through some of that hardened shell. Seeing himself on camera -- and repeatedly during the editing and production process -- brought to light just how much he had hidden away.

"That's why this film has been so cathartic," he says. "I deluded myself into thinking that I was OK. That I could handle everything. And then I see this person on-screen, and then I think, Oh, my God, that's actually me. And he's really broken."

Vargas sees his film as "an act of civil disobedience." He is anxious, excited, and nervous about how the film will be received. He describes audience reactions at the 13-city nationwide screening tour as "intense."

Indeed, the film is powerful -- but it's more than that. It is profoundly human -- flawed, impatient, heartrending, and unflinching in its depiction of the emotional roller coaster Vargas and the millions of undocumented Americans like him are thrown onto daily. Many of those peaks and valleys come in political fits and starts on the ever-pending immigration reform, while others are conveyed through much more intimate, personal interactions with Vargas's mother and family still in the Philippines. Vargas still hasn't seen his mother in person for more than 20 years.

"It was very important for me to direct the film, and to write them film, and to produce the film, and say that I'm really here and this is really my country," he explains. "The question of the film is, What did you want to do with me?"

That's a question Vargas posed directly to the Senate Judiciary Committee in February of last year, when that committee heard testimony on the importance of immigration reform. Vargas's testimony is captured on film in Documented, as he recounts his experience as an undocumented immigrant to the lawmakers on Capitol Hill, supported by his grandmother, his uncle, and fellow immigration advocates.

Vargas testifies before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Commitee in February 2013. Image courtesy of Apo Anak Productions.

Vargas testifies before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Commitee in February 2013. Image courtesy of Apo Anak Productions.

But while Documented presents that question to the U.S. government and, by extension, to the American people, Vargas stresses that it's also a crucial question for the LGBT population to answer.

"I don't think the LGBT community -- that has always fought for inclusion -- is as inclusive as it should be," says Vargas. "When you're a gay person of color, there are many struggles to deal with. There are many closets to come out of."

Admitting that he has only been to one official Pride parade -- a friend took him to San Francisco's Pride shortly after he came out when he was a teenager -- Vargas still believes most organized Pride parades are examples of "just how corporate 'gay' has become."

And that doesn't reflect the reality of the modern LGBT rainbow, he says.

"Especially the millennial gay generation, that is the most diverse that it's ever been -- this is a really big challenge for us," he explains. "And how are large LGBT organizations facing that question? Because I mean, yes, I'm talking about immigration, but this is bigger than that."

"Our equalities are tied to each other," he continues, using President Obama's recent announcement that he will sign an executive order barring federal contractors from discriminating against LGBT employees as an example. "So now, I wonder if the LGBT groups are going to start saying to the president, 'Wait, President Obama, don't you also have the executive power to stop deportations of immigrants, many of whom are LGBT, many of whom are transgender, many of whom are being detained and being kept in atrocious situations?"

Vargas wants to see the LGBT community at large -- and specifically its leading organizations and nonprofits -- embrace a more intentional, active, and vocal inclusivity.

"I would love for these organizations to insist on diversity in their ranks," says Vargas. "It's not just America that is changing, gay America is changing. And how are we reflecting that change?"

"I'm sorry, when was it that sodomy was against the law?" asks Vargas, incredulous. "When was it that being gay in this country was a mental defect -- was a psychological imbalance?"

As a gay, undocumented person of color -- who has not only a college degree but an illustrious career -- Vargas explains that his experience of America has been one of connecting the dots of his seemingly disparate identities. That's what led him to launch his nonprofit group, Define American, which he describes as an organization "challenging media and creating media in hopes of changing culture."

And the culture being challenged isn't just mainstream American media, he says.

"Look, I've been openly gay since I was 18 years old -- I came out in 1999," he explains. "And sometimes I still don't feel included or accepted. Not just me personally, but Asian people, immigrants. I just don't know if the LGBT community at large is as socially awake as it ought to be. Where are we when Trayvon Martin happened? Where are we when it comes to talk about unemployment? Health care? Immigrant rights?"

Vargas stresses that there is not a single monolithic gay "look" or "queer experience."

"To this day, I flip through Out and I flip through The Advocate and it still feels like the 1990s to me," he says.

"All of us are multitudes. When I see the gay pride flag, in the same way I see the American flag, I've always wondered: How included I am in it?"

"All I know, is we are stronger when we're together," Vargas concludes. "We are stronger when we address not just how these issues intersect, but how we as people are multidimensional."

Watch Jose Antonio Vargas's feature-length film debut when Documented airs on CNN Sunday at 9 p.m. and 11 p.m. Eastern, and again July 5 at 9 and 11 p.m. See the film's trailer below.

Jose Antonio Vargas with his mother in the Philippines. Image courtesy of Apo Anak Productions.

Jose Antonio Vargas with his mother in the Philippines. Image courtesy of Apo Anak Productions. Vargas testifies before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Commitee in February 2013. Image courtesy of Apo Anak Productions.

Vargas testifies before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Commitee in February 2013. Image courtesy of Apo Anak Productions.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes