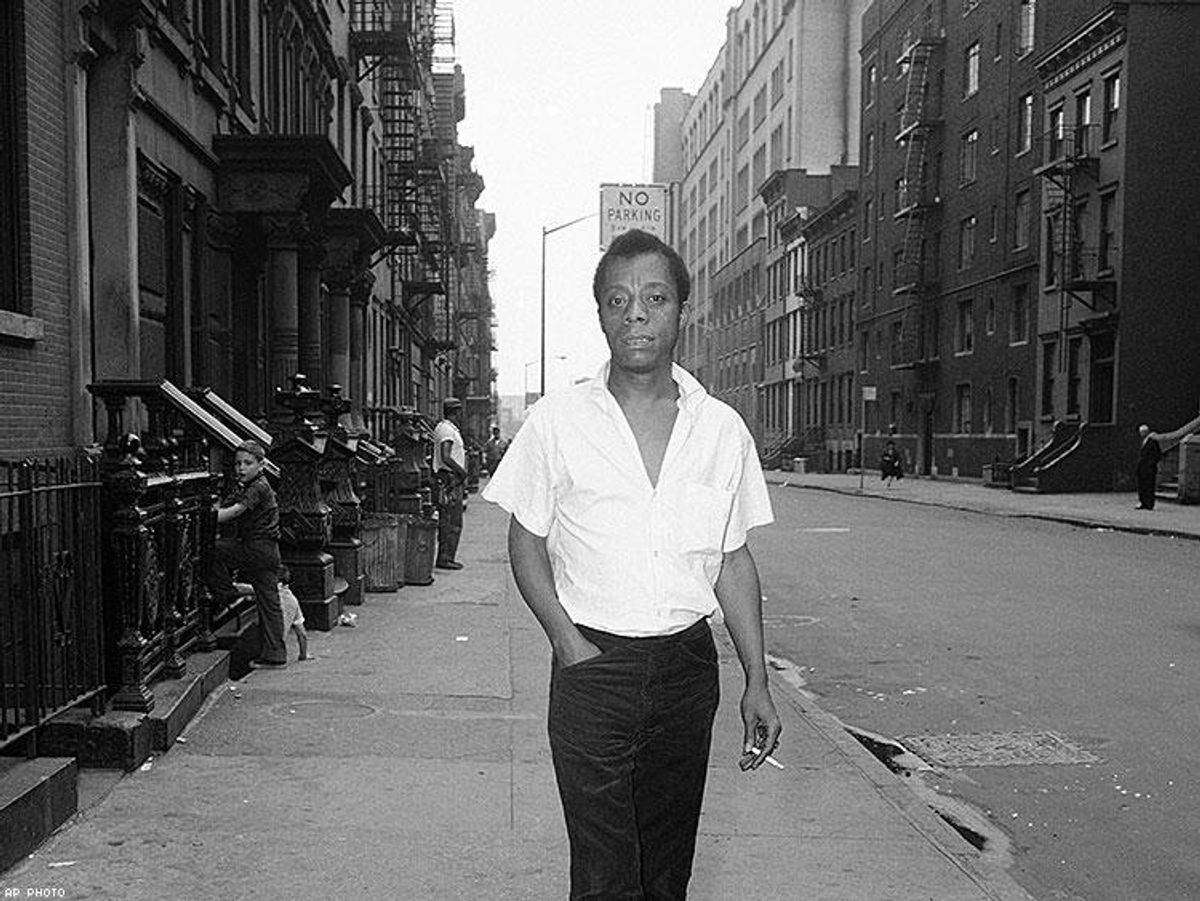

Before the presidential election, I told my friends that if Donald Trump won, I would move to Mexico City. I couldn't imagine living in Trump's America. I fantasized about moving down south and writing about what it's like to view Trump from abroad, like James Baldwin wrote about race relations and queer identity from France in the 1940s and '50s.

"I knew what it meant to be white and I knew what it meant to be a nigger, and I knew what was going to happen to me," Baldwin said in an interview with The Paris Review, on why he had to leave the U.S. for France in the '40s.

My high school history books made me doubt a Trump presidency would ever happen. Not in this country, not in the country where the Japanese internment camps are seen as a stain on our history. But that was before Trump partisans went on television to extol the virtues of those very camps that my high school teachers said we should be ashamed of -- a history that should be taught so it isn't repeated. Yet every day under Trump feels like doomsday, as if the lessons history taught us are deemed useless.

I could be an expatriate like James Baldwin, I told my friends. I imagined strolling through Mexico City like Daniel Hernandez, the queer author of Down and Delirious in Mexico City: An Aztec Metropolis, a book Hernandez wrote about making his way from Los Angeles, where he wrote for L.A. Weekly and the Los Angeles Times, to move to Mexico City, making the opposite of the trip many of our parents made to give us a shot at the American dream.

I left Mexico for the U.S. when I was a child, before I really knew what words like nationalism, patriotism, America, Mexico, and immigrant meant, as well all the other words I won't write here that Trump has used regarding the place I come from and the people who live there.

Fast-forward to 2016 -- I'm 27. A reporter. Like many other journalists, I predicted Hillary Clinton would become our next president.

But then November 8 came. I was devastated. I still remember sitting on my couch, staring at the electoral map on the television, checking Twitter, and confirming the stats with multiple sources on my laptop, unable to grasp what had just happened.

The defeat I felt wasn't because I was dying for Secretary Clinton to win but because it meant Trump had won. The man who bragged about grabbing women by the pussy because when you're famous there are no consequences. The trolls were going to get their moment, for at least four years. They didn't lose any time. Kellyanne Conway called the Clinton campaign "bitter" during a heated exchange at Harvard University. Corey Lewandowski, who was accused of attacking a woman reporter during the campaign, harassed CNN commentator Van Jones on TV. "Say it again. I didn't hear you," Lewandowski told Jones after Jones said, "You won."

Once the shock of Trump's upset wore off -- although has it really worn off, even now? -- I thought about New Yorker editor David Remnick's commentary for the magazine. His words have stayed with me since.

"An American Tragedy" was the headline on his piece published the day after the election. Yes, I know, this is coming from one of those publications that Trump and his supporters say represent "liberal coastal elites." Here's what he wrote when Trump secured the presidency: "It is all a dismal picture. Late last night, as the results were coming in from the last states, a friend called me full of sadness, full of anxiety about conflict, about war. Why not leave the country? But despair is no answer. To combat authoritarianism, to call out lies, to struggle honorably and fiercely in the name of American ideals -- that is what is left to do. That is all there is to do."

Remnick's words resonated with me because I was one of those people who thought it was best to let go and allow the country to destroy itself, but I came around. Remnick's position felt strange to me at first because it comes from a place of assumption, as if journalism will save us all or as if our roles as journalists will somehow create change or change the minds of people in red states who voted for Trump, or for voters who voted for Obama in the past and supported Trump out of frustration. Sometimes it works. The Washngton Post and The New York Times have published several incredible stories that have had impact -- Michael Flynn was forced to resign when it came to light that he had lied to the vice president about his communications with Russian leaders. Attorney General Jeff Sessions was forced to recuse himself from investigations dealing with Russian interference in the election because he lied during his confirmation hearing by claiming not to have communicated with Russians officials. He had met twice with an ambassador -- the same ambassador who cost Flynn his job as national security adviser. Regardless of how presumptuous the position may seem, I related to it. I felt a responsibility as a queer writer for a national publication. I thought, I can't leave. Where else could I see the effects of Trump but in the heart of the beast?

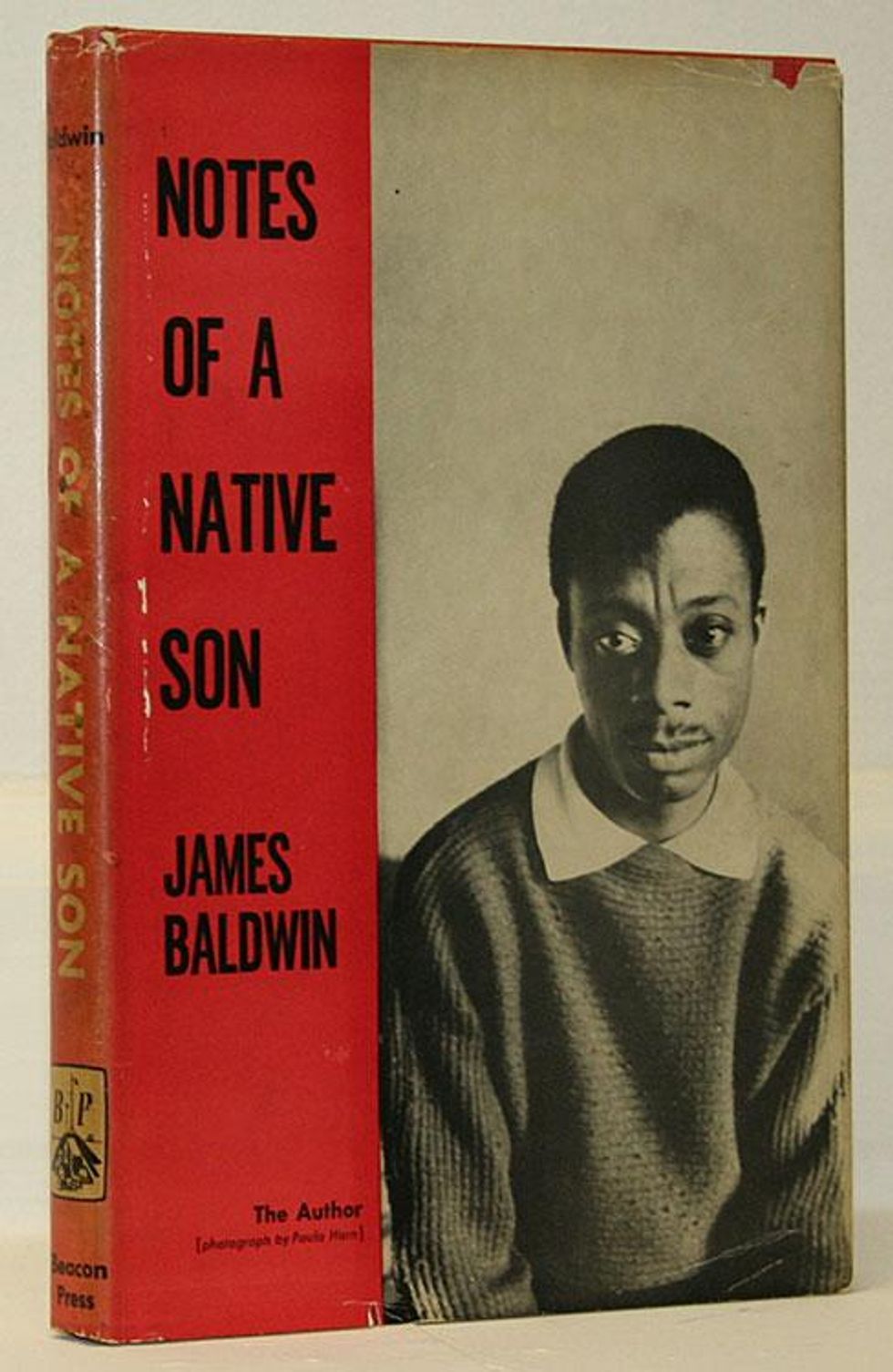

Why did Baldwin leave America in the 1940s? Imagine it. This was the decade of the Japanese internment camps, when lynchings were still a common occurrence in the South, when Zoot Suit riots were happening in Los Angeles, and when Baldwin himself faced discrimination in New York City. He wrote in Notes of a Native Son about a particular incident when he entered a restaurant and waited to be served. A white waitress told him, "We don't serve Negroes here." He was tired of hearing that phrase, and he grabbed the object nearest him: a glass mug half full of water. He wrote that he "hurled it with all my strength at her." It barely missed her, and it shattered a mirror that was behind the bar. He was able to escape the grasp of a man in the restaurant who grabbed him by the neck and hit him in the face soon after the incident. Baldwin kicked him and ran for it, barely eluding police.

Raoul Peck, director of the Baldwin-inspired documentary I Am Not Your Negro,told NPR the writer returned because Baldwin was determined to serve as a "witness." "The notion that [Baldwin] likes to use all the time is about being a witness," Peck said. "You know, in order to be a witness, you have to be there. You have to be also part actor. You have to be in the middle of the battle in order to be able to write about that battle."

Baldwin left America because of its racism, but it was racism that brought him back. While he was already back in the country, he wrote about how affected he was by an image of Dorothy Counts, a 15-year-old African-American, who was walking into a desegregated school in Charlotte, N.C., in 1963. A mob of angry white protesters is seen following and taunting her. The teenager was threatened and stoned by the protesters. She dropped out of the school after four days. "Spit was hanging from the hem of Dorothy's dress," Baldwin reportedly recalled a witness telling him. He wrote to a friend at the time, "Some one of us should have been there with her."

When I watched the documentary, I thought about how this gay black man reflected my modern-day feelings about America. But we couldn't have come from more different backgrounds. I am a Mexican lesbian immigrant woman. But as Langston Hughes famously wrote in response to Walt Whitman's "I Hear America Singing," "I, too, am America." That is America -- that is what unites Baldwin and me.

Baldwin came back self-realized, with conviction, with a passion to take on the American project of justice. When he returned, he was determined to be involved in the civil rights movement. He rubbed elbows with Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, and he wrote about this experience before his sudden death -- writings that formed the basis of I Am Not Your Negro, which was nominated for an Oscar.

I think a lot about how different Baldwin's relationship with America was from my own, but also how different everyone's was -- there were the whites who supported the abolition of discriminatory Jim Crow laws, but then there were the whites who didn't. They all had justifications for their positions. It's the current state of our politics too. Politicans and pundits battle it out every day on Twitter and on the big television networks, and it isn't often that either side reaches out to the other or that both agree to meet in the center. Baldwin had his own thoughts on this, which he revealed in an interview with The New York Times:

"I left America because I had to. It was a personal decision. I wanted to write, and it was the 1940's, and it was no big picnic for blacks. I grew up on the streets of Harlem, and I remember President Roosevelt, the liberal, having a lot of trouble with an anti-lynching bill he wanted to get through the Congress -- never mind the vote, never mind restaurants, never mind schools, never mind a fair employment policy. I had to leave; I needed to be in a place where I could breathe and not feel someone's hand on my throat. A lot of young Americans white or black, rich or poor, have wanted to get away, as a means of getting closer to themselves. For me France was the beginning of a writing life; I wrote Go Tell It on the Mountain there. It was there I began the struggle with words."

In America, his otherness, his difference was his race. In France, he felt the freedom to write and recognize himself as an outsider because of his English: "It was in France that I could start a career of writing English because there I was not able to speak French and so I was driven to recognize myself as an outsider that way, not as a black man, but as an English-speaking person." And he didn't write this at the time, but I am assuming his sexuality also played a part.

Baldwin died in the U.S., in New York, the state where he developed his political consciousness, his writing sensibility, but also his general sensibility about the world that gave him a foundation to critically analyze the world as a public intellectual and novelist. He had a reference point that many others at the time didn't. It's why his words, though they have long outlived him and will continue to, resonate with an audience in 2017. He's the perfect guide to living in Trump's America.

As The New Yorker wrote about him: "During his wanderings, Baldwin warned a friend who had urged him to settle down that 'the place in which I'll fit will not exist until I make it.'"