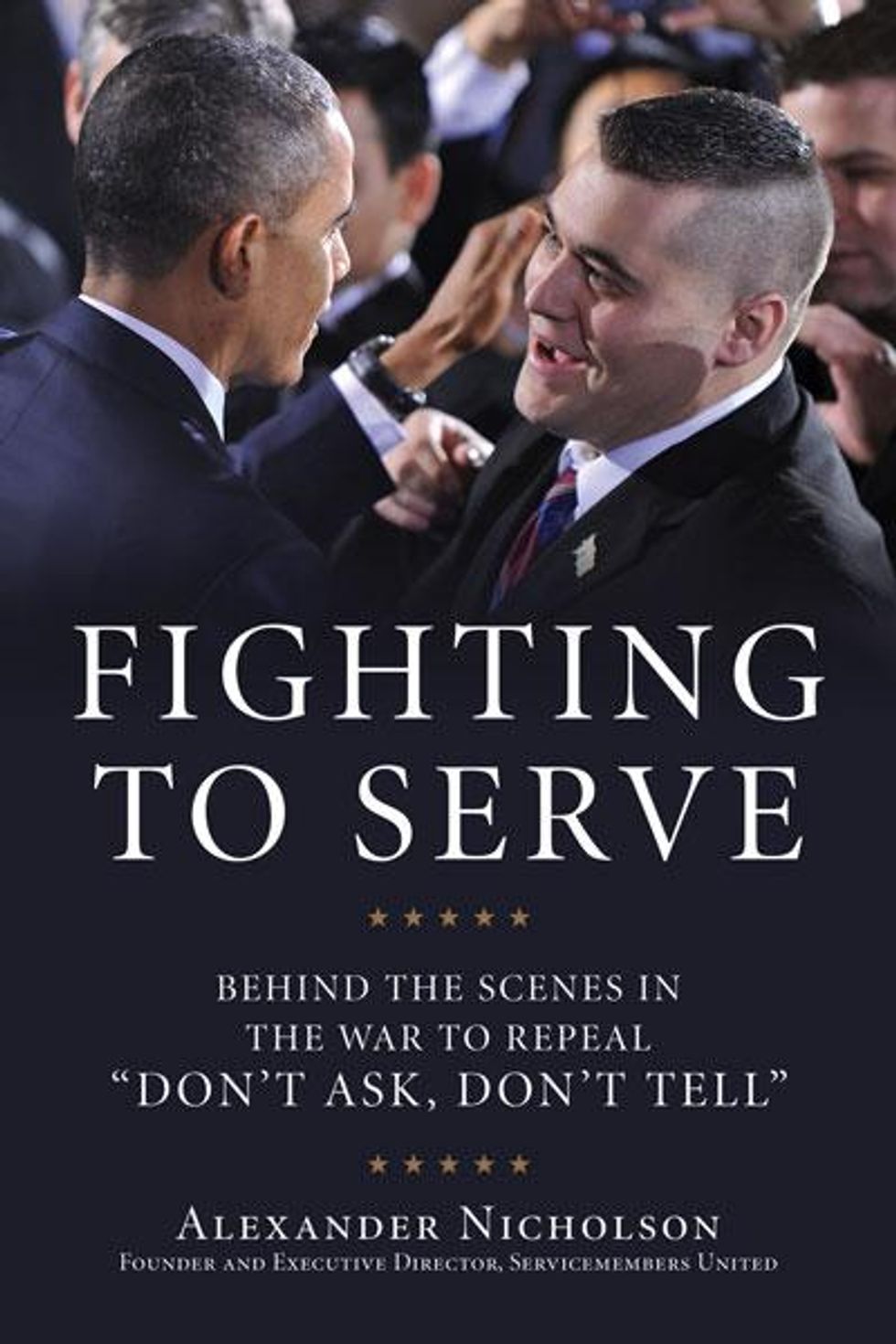

The repeal of "don't ask, don't tell" had a provision that some gay activists saw as risky. The caveat required the entire military to be trained on integrating out troops, and President Obama, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the secretary of Defense each had to certify that the armed services had been properly trained. In a new book, Fighting to Serve, Alexander Nicholson explains the delicate actions around that decision. Nicholson, the executive director of Servicemembers United, writes that endorsement of the incremental repeal by his organization as well as the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network gave a sort of stamp of approval, alerting gay people that this time the Pentagon could be trusted to work in their favor. Here, Nicholson shares the back-and-forth that went on behind the scenes between members of Gay Inc., Congress members, the Pentagon, and the president.

-----

Our endorsement, along with SLDN's, was critical to legitimizing this concession, and the new repeal amendment as a whole, to the gay and progressive communities. But the idea for this second concession did not come from Servicemembers United. It did not come from SLDN or HRC either. As soon as I saw it in writing, weeks before it was announced publicly, I knew it was brilliant and I wished that I had thought of it. But the conduit through which it came was Winnie Stachelberg at the Center for American Progress. To my knowledge Stachelberg hadn't come up with this idea herself either, and it likely didn't even come from within her organization, but CAP nevertheless was the organization that was given the proposal to vet, to present to our coalition, and eventually to present to our allies in the Senate, namely Senators Joseph Lieberman and Carl Levin, for their buy-in.

Stachelberg had been with HRC for eleven years, serving as their political director and then as the vice president of the HRC Foundation before she went over to former White House chief of staff John Podesta's new progressive think tank, the Center for American Progress. Winnie's former ties to HRC and CAP's close ties with the administration--Podesta was also the head of the Obama transition team--meant that Stachelberg got roped into the inner DADT circle with us. She often supported HRC's positions in the coalition, which is why they liked her being there, but she was actually pleasant and personable, which is why I liked her being there too.

Others outside of the inner circle, however, did not understand why Stachelberg was a part of DADT repeal deliberations. She and CAP did not have a constituency, they argued, and their close ties to the Obama White House meant that she was inherently distrusted by bloggers and many independent activists. But I often defended Stachelberg's involvement in our coalition. Even though I grew to trust her less as time went on, I still liked her, and I thought she was a lot more of a decent human being than many of the others involved. And we needed some pleasantness to balance out the lack thereof elsewhere in the coalition.

When Stachelberg introduced the idea of the conditional trigger to the rest of us in the inner DADT circle at a meeting in Senator Lieberman's office in early May, I immediately perked up and thought we had found our magic key. This trigger mechanism was a perfect match for the requirements of the Pentagon, which wanted control over the rate of change--and desperately wanted to hold off the start of that change until after their nine-month-long review was completed. As far as I was concerned, this option of passing the repeal law now but stipulating that it would only take effect when the top defense officials gave the go-ahead was brilliant. Once legislative repeal was locked in, Congress would be out of the picture. Then, as soon as the chairman and the secretary were ready, they would sign off on the certification, and of course the president would too, and we would be done. This seemed like the perfect solution to pick up the last few votes we needed on the Senate Armed Services Committee in order to proceed. And as it turned out, it was.

But Dr. Aaron Belkin at the Palm Center had a change that he wanted added in: a third and wholly unnecessary concession. Aaron was not directly involved in the repeal movement's politics, but he certainly thought he was abreast of them, and he seemed to desperately want some sort of fingerprint on the final version of the legislation. Belkin began almost unilaterally lobbying to have the nondiscrimination language taken out of the bill, and as he was so good at doing, he began manufacturing momentum for this idea. He wrote an op-ed in its favor for General John Shalikashvili, whose New York Times piece in support of DADT repeal had been so influential, then got General Shali's son to get Shali to sign off on it. Belkin began declaring in public that we did not have the votes for repeal without removing the nondiscrimination language, but he would not have known whether we did or not. He was never in the room with the coalition, and no one else associated with the Palm Center ever was either. He did not know the vote count directly from Senate offices. His information was second- and third-hand at best, yet here he was unilaterally giving away the coveted nondiscrimination language that ensured that the military could never again revert to any sort of antigay policy.

All of us who were actually working on the political parts of DADT repeal were furious. We knew that taking out the nondiscrimination language would not pick up one single vote--the two concessions we'd already made picked up the votes we needed on committee--and we hoped that Belkin's lobbying effort had not foreclosed upon our options for keeping that language in. But once your interest group community puts a concession out on the table, or someone on your side unilaterally puts it out there for you, it's hard to walk it back. What the White House and the Pentagon essentially did was to take all of the concessions that had been publicly floated, read the writing on the wall, and reluctantly agree to support a repeal amendment that included all three of them.

We found out that the White House and the Pentagon were finally going to agree to support the new repeal amendment when we were summoned to yet another meeting at the White House on Monday, May 24. Foreshadowing their slightly greater level of cooperation, this meeting took place in the West Wing, in the Roosevelt Room to be precise, instead of in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. I had only been in the West Wing once before, and I entered through the entrance across from EEOB then. This time, I entered through the gate directly north of the West Wing. Since I had never been through this entrance before, I had no clue which door of the actual building to go into, so at first I accidentally walked into the press briefing room. The only reason I recognized I was in the wrong place was because it looked almost exactly like the press briefing room from the TV series The West Wing, and for a moment I secretly hoped I would see C. J. Cregg come around the corner and make a witty comment. A jovial reporter hanging out by the door quickly picked up on the fact that I was lost and told me that the West Wing lobby was the next door down.

A tall, sharp marine opened the outside (correct) door for me, and another marine opened the second door inside. I wondered immediately if they knew why we were there and what they thought about DADT. When I got inside, I noticed that I was one of the last to arrive. Waiting in the lobby already were some of the usual suspects, including David Smith and Joe Solmonese of HRC; Winnie Stachelberg of CAP; Aubrey Sarvis of SLDN (this time he was actually invited); and Tobias Wolff, a law school instructor who had volunteered on the Obama campaign and who was clearly there to serve as the administration's cheerleader-in-chief. After a few awkward hellos, I joked with Aubrey that we had a bit of a Romeo and Juliet situation on our hands, as one of his staff members had started dating one of mine. He laughed and said that he was never up on those things.

Brian Bond soon came out to greet us and ushered us into the Roosevelt Room. Since the room was an enhanced-security area, we had to leave our cell phones outside. We then had a good ten minutes or so to chat awkwardly among ourselves and with the few White House staffers who were minding us. While the others commented on the various paintings that adorned the wall, my eye quickly darted to a glass-encased Medal of Honor that was on display in the southeast corner of the room. Although I could not see the detail of the medal itself from that far away, I recognized the characteristic light blue ribbon from which Medals of Honor always hung.

Brian Bond soon came out to greet us and ushered us into the Roosevelt Room. Since the room was an enhanced-security area, we had to leave our cell phones outside. We then had a good ten minutes or so to chat awkwardly among ourselves and with the few White House staffers who were minding us. While the others commented on the various paintings that adorned the wall, my eye quickly darted to a glass-encased Medal of Honor that was on display in the southeast corner of the room. Although I could not see the detail of the medal itself from that far away, I recognized the characteristic light blue ribbon from which Medals of Honor always hung.

I have been in the Roosevelt Room several times now, and I have yet to wander over to that display case and see whose medal that is. I am always in awe of the incredible sacrifice and selflessness required to earn that honor, and I even get a little emotional when I hear the Medal of Honor talked about on the news. Some of the people in that room were completely oblivious to being in the presence of the nation's highest and most sacred military honor, but there they were, and there I was.

We were eventually joined by deputy chief of staff Jim Messina, who apparently was still running the DADT issue for the White House; Tina Tchen, director of the Office of Public Engagement; and a few folks from White House Counsel's office. Chris Neff, the Palm Center's "person in DC," was strangely permitted to join us by phone from Australia, where he was living.

The meeting was rather quick and tense. Tchen first told us that news of the meeting had already leaked, and that the White House press office was getting calls from Politico asking if they could confirm that a meeting with gay activists was taking place. It occurred to me then that putting us all in an enhanced-security conference room and then having someone dial in from Australia seemed like a huge contradiction and a huge confidentiality risk, politically speaking. For all we knew, the caller could easily record the entire meeting on the other end of the line, and on the other side of the globe. That would actually have been useful, given how quickly the participants had started lying after the previous White House meeting.

After the customary confidentiality admonishments, Messina rather coldly informed us that the White House would be issuing a statement later that day regarding the new repeal amendment that had been proposed. The statement was clearly an attempt to reluctantly jump on board a fast-departing train. But it would not even come from the president in the end. It would come from Peter Orszag, the director of the Office of Management and Budget. Having an administration official not involved in the DADT issue send the White House's position out in the form of a letter was obviously meant to downplay the significance of the tepid and reluctant endorsement.

When we tried to press the White House staff for more--a guarantee of an administrative nondiscrimination policy after legislative repeal, for example--all we got was "This is where we are right now." The message was clear: the administration was now on board, but they were not happy about it. They were upset that we had pushed them onto the train a year earlier than they wanted to get on board. And they were not going to provide any additional fuel for that train or make us feel better about the ride ahead.

Orszag's statement was soon followed up with an equally tepid statement of support from Secretary Gates and Chairman Mullen, although it was still one we could work with. Their statement said that although they would have preferred legislative action after their nine-month study had been completed, they could support the new proposed amendment.

It was completely incomprehensible that all of these men would not fully support this amendment. Gates and Mullen had testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee that they both supported the president's goal of ending DADT. This amendment did that, and it did it when, and only when, those two men specifically said the military was ready. If they said it was ready after the study was finished, they would be allowed to make that change happen. If they did not think it was ready for another fifty years, they could block the change for another fifty years. We knew that would never happen, of course, but the important point was that this amendment gave them that power. But the Pentagon is often an incomprehensible beast. Sometimes ego and other factors go into equations about what the Pentagon will support, and often the reality of ticking political clocks do not. In any case, although it was not what they really wanted and it was not what we really wanted, we had gotten what we needed to push forward. It was all about sufficiency, and both the amendment and the White House and Pentagon statements were minimally sufficient to move ahead.

Given that news of the meeting had leaked to Politico before we even got there, it was no surprise that reporters started calling almost as soon as I walked the two blocks back to my office. I tried to avoid media calls and e-mails for a while, but one small-time reporter caught me picking up the phone because of an unrecognized area code (most media calls were coming from DC, New York City, and Los Angeles area codes). This reporter for a small gay publication seemed to think she had hit the jackpot by getting me on the phone, and she started barraging me with frantic questions about the meeting. When I politely told her that she would need to try someone else for information about the meeting, she chastised me for not wanting to give her what would become publicly available information later anyway. That certainly was not the way to get me to open up, and after that I would not give her anything, not even a comment on what the weather had been like on the way to and from the meeting.

But news of the meeting did make it out, and once again the conspiracy theories abounded about what secret plans had been hashed out between Gay Inc. (into which we were now ironically cast) and the White House at this meeting. The biggest and most inaccurate collective public conclusion from the whole episode was that this was the meeting where the "deal" about the amendment had been worked out and agreed upon by all parties. Clearly, that was far from the truth.

Most of the amendment language had been developed weeks prior and had already been discussed and debated within the organizational and Capitol Hill DADT coalition. It had been presented as a unanimously supported option to Senator Levin, who liked the idea and agreed to push it forward as chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. There was no negotiation with the White House, contrary to popular belief and popular reports. Had there been, we might have ended up with even less.

By the time we got to the Roosevelt Room, the final amendment language was a done deal. At this point, the White House and the Pentagon could either be with us or they could be against us. They chose reluctantly to be dragged along. But to hear them tell it later, they had been conducting the train the whole way.

----

Excerpted with permission from Fighting to Serve: Behind the Scenes in the War to Repeal "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" by Alexander Nicholson, published by Chicago Review Press, October 2012. The book is available to purchase though IPGbook.com, BN.com, Amazon.com, and independent bookstores.

Brian Bond soon came out to greet us and ushered us into the Roosevelt Room. Since the room was an enhanced-security area, we had to leave our cell phones outside. We then had a good ten minutes or so to chat awkwardly among ourselves and with the few White House staffers who were minding us. While the others commented on the various paintings that adorned the wall, my eye quickly darted to a glass-encased Medal of Honor that was on display in the southeast corner of the room. Although I could not see the detail of the medal itself from that far away, I recognized the characteristic light blue ribbon from which Medals of Honor always hung.

Brian Bond soon came out to greet us and ushered us into the Roosevelt Room. Since the room was an enhanced-security area, we had to leave our cell phones outside. We then had a good ten minutes or so to chat awkwardly among ourselves and with the few White House staffers who were minding us. While the others commented on the various paintings that adorned the wall, my eye quickly darted to a glass-encased Medal of Honor that was on display in the southeast corner of the room. Although I could not see the detail of the medal itself from that far away, I recognized the characteristic light blue ribbon from which Medals of Honor always hung. When we tried to press the White House staff for more--a guarantee of an administrative nondiscrimination policy after legislative repeal, for example--all we got was "This is where we are right now." The message was clear: the administration was now on board, but they were not happy about it. They were upset that we had pushed them onto the train a year earlier than they wanted to get on board. And they were not going to provide any additional fuel for that train or make us feel better about the ride ahead.

When we tried to press the White House staff for more--a guarantee of an administrative nondiscrimination policy after legislative repeal, for example--all we got was "This is where we are right now." The message was clear: the administration was now on board, but they were not happy about it. They were upset that we had pushed them onto the train a year earlier than they wanted to get on board. And they were not going to provide any additional fuel for that train or make us feel better about the ride ahead.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered