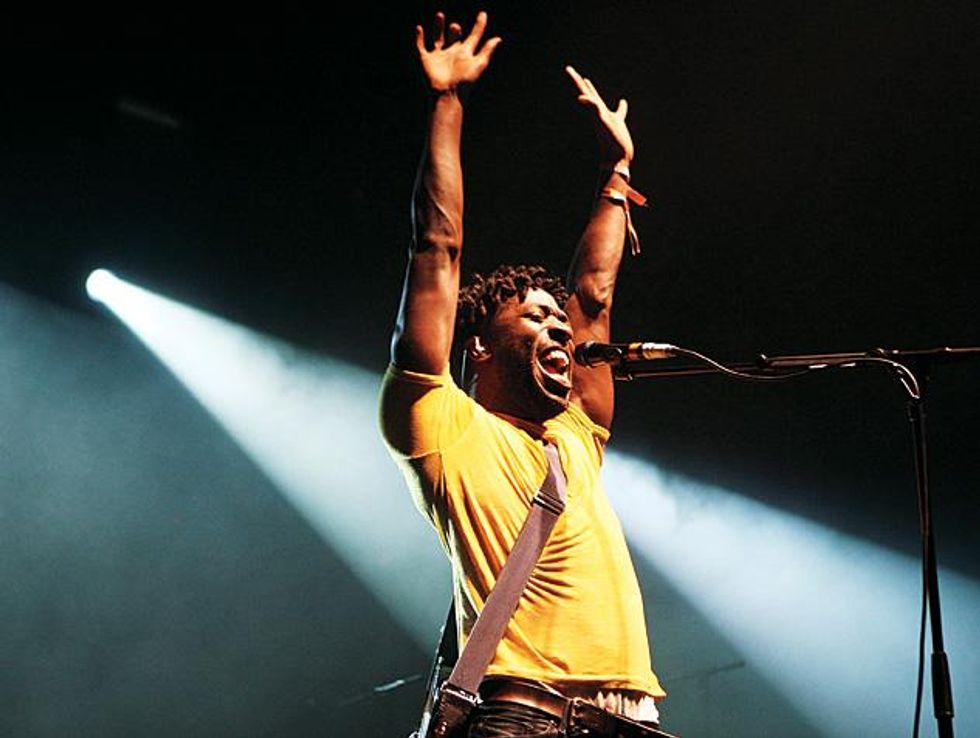

Madonna is such a mega-fan of British rock band Bloc Party, lead singer and rhythm guitarist Kele Okereke told a Chicago Tribune reporter, that the most amazing thing about performing at Live Earth 2007 at Wembley Stadium was that the iconic singer, who was also appearing that day, came in their dressing room to see the band.

"Our tour manager is this guy from Scotland that doesn't know much about popular culture and popular music," he told reporter Matt Pais. "So when she came in, he alerted security and security dragged her out. They had her head in a headlock, and they were putting her out of the dressing room. It was really surreal, and everyone stopped speaking. And the only thing we could hear is Madonna cursing and saying she's gonna kill these guys."

The guys who hauled out the Queen of Pop in a headlock? That's the kind of story a band can dine out on for ages. Except not a word of it was true. That fib, Okereke says, was later picked up by the National Enquirer. "That was probably one of my proudest moments," he says now. "Just as long as it's not libelous. Madonna flipping out? It's believable, right?"

Other lies and misdeeds? In late 2011 he told U.K. music publication NME he was worried he was being replaced as Bloc Party's lead singer: "I was actually having lunch about three weeks ago...and I saw somebody walk past and I recognized the haircut. It was [guitarist Russell Lissack]. I was like, 'Hey!' but he didn't see me and I followed him around the corner and then I saw [drummer Matt Tong], [bassist Gordon Moakes], and Russell all standing outside this rehearsal space. They all went inside.... I hope I haven't been fired. I don't really know what's going on, because we haven't really spoken recently and I'm a bit too scared to ask."

So this spring, when Bloc Party announced new tour dates and began recording tracks for a yet-to-be named new album, one that included lead singer Kele Okereke, some confused music watchers and reporters were scratching their heads.

The story of being replaced also was utterly untrue. "It was completely bullshit," he says over breakfast at La Bottega in New York's Chelsea neighborhood. "I was quite proud of it." So what's the deal with the tall tales? "That was me losing interest in an interview. You can tell when a journalist is trying to lead you down a path, when they have written the story in their head and the interview is just about filling it in. It's hard to go along with that. That's why recently I've been making lots of stuff up in interviews. It's got me into lots of trouble, but that's only when I'm not engaged. Don't worry. I'm fully engaged now."

Okereke was born in Liverpool to Nigerian immigrant parents and was raised on the northeast edge of London, near Essex. One of his earliest memories of music is seeing American rap duo Kris Kross on the U.K.'s music chart television show Top of the Pops. "I remember they were just two young black kids, it was really inspiring. I was 9 or 10."

His sister, who is one year older, had a sizable collection of pop and R&B albums as well as, significantly, an acoustic guitar. "That was the most important development in terms of my musical identity," he says. "She had a chord book, and I taught myself to play guitar. Guitar music was something that I could aspire to at that time." Okereke began to write songs and lyrics but didn't have anyone with whom to collaborate. "If I'd known someone who could sing, I would have just gotten them to sing. But I didn't know anyone. I got more competent the more I did, but I wasn't one of those kids who was singing to themselves on the street corner."

At the Reading Festival in 1999, Okereke asked Lissack, a guitarist and friend of a friend, to form the band that later became Bloc Party. "He was dedicated, had a pure streak," says Okereke. "I had to work up the courage to ask him, because I didn't know him too well." Moakes and Tong joined later.

While forming the band, Okereke came out as gay to his family. "I was out as a teenager, just not to my parents and family, and then I told my family in 2000. That's when I really, really cut the strings." His parents threw him out of the house, and for a week they didn't speak at all. "I wasn't sure what was going to happen, but it was the best period of my life--I say this hand on heart." Okereke found an apartment with two women in East London, and he says that for the first time in his life, he felt he could be himself. "Now there's nothing in my life I have to hide. I think when that realization flows through you and when you know you can be who you are, then everything else is secondary."

Over a decade later, his familial situation has evolved. "I'm closer now with my parents, and I speak to my mum nearly every day. And I miss them when I'm away from them, whereas when I was a teen I couldn't wait to be away from them. It's been a journey. It was years of having to tiptoe around the issues, but I'm glad that I did it." Nevertheless, he recognizes that because of their experiences in Nigeria, they have difficulty even comprehending homosexuality.

"They weren't into it at all, and they are still very Catholic and from a place where there are no visible gay people. They don't quite understand it. But they love me, and they understand that I'm happy, and we're finding a way."

Okereke describes Bloc Party's first songs as naive, scrappy. "Although we could all play quite well, I don't think as a band we had a collective discipline," he says. "We were really just kind of railing against all the other guitar bands we heard in Britain doing a safe, singer-songwriter-y kind of sub-Coldplay sound, and we just didn't want to do that. We wanted to make something that had a bit of fire in it, and we just kept that up until making the record Silent Alarm."

The band got its big break when its demo of the song "She's Hearing Voices" made its way into the hands of a BBC 1 radio DJ. The band was signed to a record deal in 2003. Silent Alarm was released in 2005 and reached number 3 on the U.K. charts. It was a critical smash, hailed as mature, expansive, arty, and the 2005 answer to Franz Ferdinand. It achieved gold certification within 24 hours of its European release.

But until the band had been signed, Okereke, then an English literature student at King's College London, kept his musical ambitions hidden from his parents. "I didn't tell them until we had a record deal, because I knew they'd freak out. But I knew what I was doing." He took classes until it was clear the band was going to be signed, at which point he stopped attending lectures.

"The one thing that guides you is a very intense sense of passion about it," he says of starting a band from scratch. "There are no rules, but you learn because you have to, because it's important to you. And I'm still learning now. We're making this record now and we're still learning about things. It's a very peculiar experience. It's like a marriage between four people."

Bloc Party released A Weekend in the City in 2007 and Intimacy in 2008. Both albums performed very well on U.K. charts, peaking at number 2 and 8 respectively, and Intimacy entered the Billboard 200 charts in the U.S. at number 18. At the Reading Festival in 2009, Okereke told audiences, "We won't be back here next year...or the next few years after that." He's candid that the band members' relationships weren't really in their best condition by the end of the last record, and initially none of them was sure if or when there'd be another collaboration. The band took a sabbatical.

In June 2010, Okereke released The Boxer, a solo album recorded as Kele, no surname. It was well reviewed, both at home and stateside, as a pop-rock album with driving dance beats and more lyrical complexity than the bulk of dance albums. In the video for "Tenderoni," the album's first single, Okereke's hands are taped, and he's hooded, a boxer training for the ring. He told New York magazine that the name of his album "came to me last year when I was thinking about making the record...I definitely had to toughen up in certain ways and be focused on what I wanted to achieve. Someone standing on his own has no one to rely on but himself."

Navigating fame and the media took some on-the-job training too. Reserved when not onstage, Okereke has been described many times as shy or suspicious. "When I started this I was a lot younger," he acknowledges. "Do I seem shy?" He doesn't. "I think maybe in the beginning I was a bit cynical, a bit suspicious about the whole process of interviews and star-making. I think people mistook my shyness for being a bit disinterested in the whole process."

But it wasn't disinterest that queer fans and LGBT media outlets were sensing. Though out to his friends and family, he refused to discuss sexuality in interviews, saying that because his songs didn't deal with sexual orientation, it made little sense for him to discuss his own.

"I was always slightly conscious about the angle that discussing me being gay was going to take in the U.K.," Okereke says. "It seemed like something everybody was hinting at and alluding to." Interviewers and media accounts started describing him as closeted, including a 2006 article in the Observer Music Monthly's Gay Issue, and Okereke felt hounded.

"I've never had any problems being out and open, but I didn't like feeling as if I were being pressured into being a role model or a spokesperson for people," he says. "I was just a kid, and the decision wasn't mine. It felt like everybody else had an agenda and that I had to play along. Yeah, in the start of my career I did have a big problem with that, but then you realize it is important to people to share experiences. You're an artist, you're outside of the boundaries that ordinary people are living in, and you do have a duty to speak up. You really do. I guess it was just realizing that."

Role model is a heavy mantle to carry, though. "I have trouble deciding what socks to wear every day, and the idea of being a spokesperson for people, the idea that your words go on and have a life outside of you, it was just a bit intimidating. I'm still working out who I am. I'm still working out what I stand for. I don't begrudge anyone for wanting to know about me. It's up to me to know how much to disclose. I've learned this over the years, but I'm not stupid. I know exactly what I'm saying to people. Some things will always be private. Some things will only be things that I know. And that's good for me because I will always own that part of me."

Owning part of himself, of his music, is something he's thought a lot about. "That's the hardest thing about making music," he says, "because when it's out in the public domain it's not really yours. Everyone has an opinion of it, and everyone else wants to claim parts of it. My favorite period is always the writing, because that's when you're pulling stuff out of nothing. It's yours. Once it's out there it doesn't feel like that anymore."

The new Bloc Party album and another writing project are his priorities now. "I'm writing a book at the moment, a book of short stories set in New York, and it's been my main preoccupation for the last year," he says. "And I'm noticing now that we're assembling the record that a lot of those ideas I was exploring in the book have bled into the record, lyrically at least. I don't know if the book will ever see the light of day, but I'm enjoying doing it. It's almost finished."

As Kele, he released the EP The Hunter late last year. His solo projects have been "a brilliant experience," and though he's not sure what form they'll take, there's more to come. But he's keeping specific plans, if there are any, to himself: "I don't know what the future is going to be with Bloc Party, but I do know being creative is part of my blood. It's part of me, and I'll be very surprised if there's not another album in me."

New York, where he's been living for the past year, has been invigorating, he says. "I've been able to have a very Bohemian lifestyle, just writing and walking slowly around and seeing what there is, in a city that's probably the most intense, work-driven city on the planet. I've been able to witness or observe a way that people interact completely removed from the situation. And I'll never forget this time."

But maybe there's a bit of downtime awaiting him after the new album and a tour. "Part of me is thinking that I need to just do nothing for a while, just be still for a while, because I won't be for the next year and a half." And that's the truth.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered