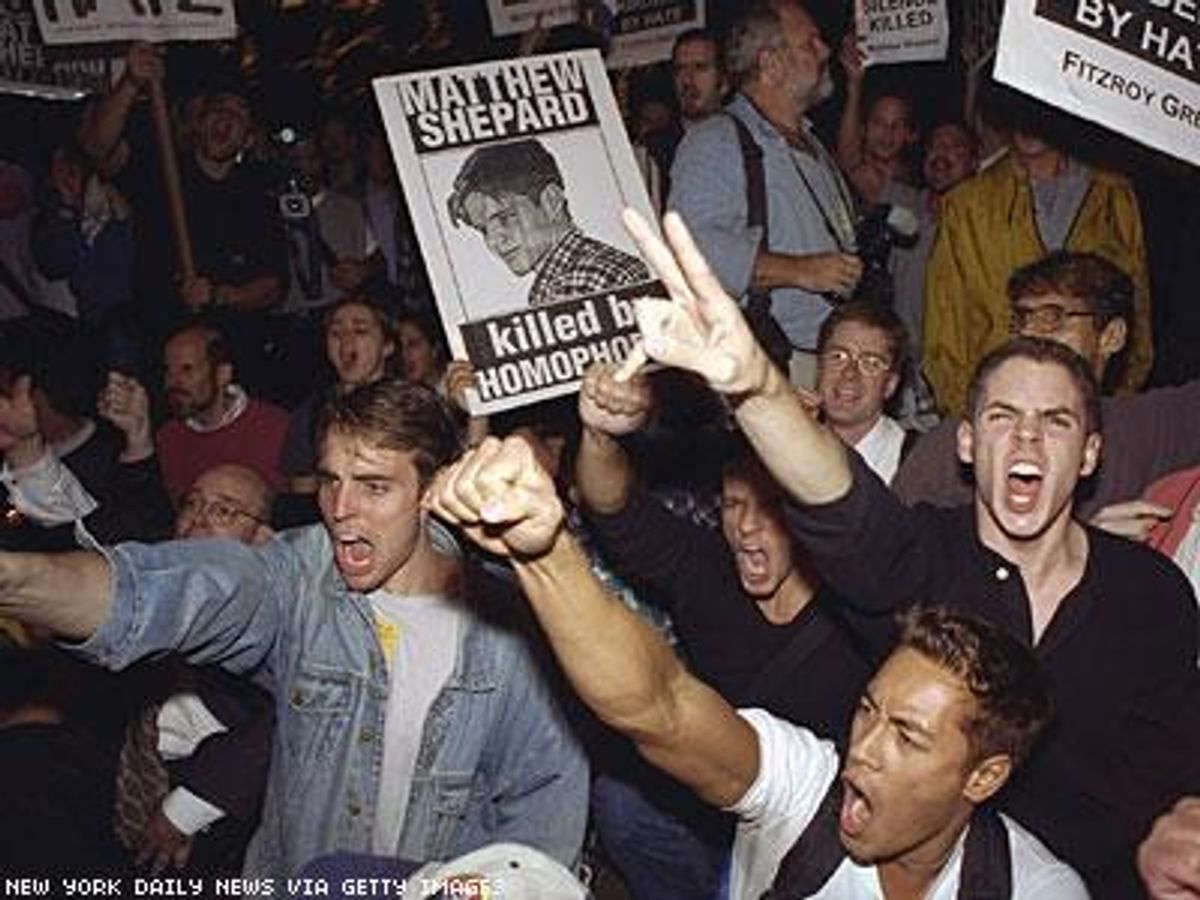

What if nearly everything you thought you knew about Matthew Shepard's murder was wrong? What if our most fiercely held convictions about the circumstances of that fatal night of October 6, 1998, have obscured other, more critical, aspects of the case? How do people sold on one version of history react to being told that facts are slippery -- that thinking of Shepard's murder as a hate crime does not mean it was a hate crime? And how does it color our understanding of such a crime if the perpetrator and victim not only knew each other but also had sex together, bought drugs from one another, and partied together?

None of this is idle speculation; it's the fruit of years of dogged investigation by journalist Stephen Jimenez, himself gay. In the course of his reporting, Jimenez interviewed over 100 subjects, including friends of Shepard and of his convicted killers, Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson, as well as the killers themselves (though by the book's end you may have more questions than answers about the extent of Henderson's complicity). In the process, he amassed enough anecdotal evidence to build a persuasive case that Shepard's sexuality was, if not incidental, certainly less central than popular consensus has lead us to believe.

Of course, none of what Jimenez discovered changes the fact that Shepard was horribly murdered, but it may change how we interpret his murder. For many of us, the crime was not simply one family's tragedy -- it symbolized our vulnerable, uncertain place in the world. For many heterosexuals it challenged the myth of America as a guarantor of equality and liberty.

All that soul-searching may have felt necessary, especially in light of the legislation the case inspired, but was it helpful in getting at the truth? Or did our need to make a symbol of Shepard blind us to a messy, complex story that is darker and more troubling than the established narrative?

In The Book of Matt, Jimenez examines the laudable, if premature, effort on the part of two of Shepard's friends to alert the media to what they believed to be a crime of hate. At the time, Shepard was still fighting for his life. By the time he died, five days later, the question had been firmly settled, as news reporters and gay organizations like GLAAD rushed in. As JoAnn Wypijewski wrote in a brilliant 1999 piece for Harper's Magazine, "Press crews who had never before and have not since lingered over gruesome murders of homosexuals came out in force, reporting their brush with a bigotry so poisonous it could scarcely be imagined."

Add to that a president who needed to expiate his sins against the LGBT community, still recoiling from the double whammy of DOMA and "don't ask, don't tell," and Shepard's posthumous status as gay martyr was sealed. The defendants didn't aid themselves by claiming they'd lured Shepard into their car and then flipped out when he came on to them.

But in what circumstances does someone slam a seven-inch gun barrel into their victim's head so violently as to crush his brain stem? That's not just flipping out, that's psychotic -- literally psychotic, to anyone familiar with the long-term effects of methamphetamine. In court, both the prosecutor and the plaintiffs had compelling reasons to ignore this thread, but for Jimenez it is the central context for understanding not only the brutality of the crime but the milieu in which both Shepard and McKinney lived and operated.

By several accounts, McKinney had been on a meth bender for five days prior to the murder, and spent much of October 6 trying to find more drugs. By the evening he was so wound up that he attacked three other men in addition to Shepard. Even Cal Rerucha, the prosecutor who had pushed for the death sentence for McKinney and Henderson, would later concede on ABC's 20/20 that "it was a murder that was driven by drugs."

No one was talking much about meth abuse in 1998, though it was rapidly establishing itself in small-town America, as well as in metropolitan gay clubs, where it would leave a catastrophic legacy. In Wyoming in the late 1990s, eighth graders were using meth at a higher rate than 12th graders nationwide. It's hardly surprising to learn from Jimenez that Shepard was also a routine drug user, and -- according to some of his friends -- an experienced dealer. (Although there is no real evidence for supposing that Shepard was using drugs himself on the night of his murder).

Despite the many interviews, Jimenez does not entirely resolve the true nature of McKinney's relationship to Shepard, partly because of his unreliable chief witness. McKinney presents himself as a "straight hustler" turning tricks for money or drugs, but others characterize him as bisexual. A former lover of Shepard's confirms that Shepard and McKinney had sex while doing drugs in the back of a limo owned by a shady Laramie figure, Doc O'Connor. Another subject, Elaine Baker, tells Jimenez that Shepard and McKinney were friends who had been in sexual threesome with O'Connor. A manager of a gay bar in Denver recalls seeing photos of McKinney and Henderson in the papers and recognizing them as patrons of his bar. He recounts his shock at realizing "these guys who killed that kid came from inside our own community."

Not everyone is interested in hearing these alternative theories. When

20/20 engaged Jimenez to work on a segment revisiting the case in 2004, GLAAD bridled at what the organization saw as an attempt to undermine the notion that anti-gay bias was a factor; Moises Kaufman, the director and co-writer of

The Laramie Project, denounced it as "terrible journalism," though the segment went on to win an award from the Writers Guild of America for best news analysis of the year.

There are valuable reasons for telling certain stories in a certain way at pivotal times, but that doesn't mean we have to hold on to them once they've outlived their usefulness. In his book,

Flagrant Conduct, Dale Carpenter, a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School, similarly unpicks the notorious case of

Lawrence v. Texas, in which the arrest of two men for having sex in their own bedroom became a vehicle for affirming the right of gay couples to have consensual sex in private. Except that the two men were not having sex, and were not even a couple. Yet this non-story, carefully edited and taken all the way to the Supreme Court, changed America.

In different ways, the Shepard story we've come to embrace was just as necessary for shaping the history of gay rights as

Lawrence v. Texas; it galvanized a generation of LGBT youth and stung lawmakers into action. President Obama, who signed the Hate Crimes Prevention Act, named for Shepard and James Byrd Jr., into law on October 28, 2009, credited Judy Shepard for making him "passionate" about LGBT equality.

There are obvious reasons why advocates of hate crime legislation must want to preserve one particular version of the Matthew Shepard story, but it was always just that -- a version. Jimenez's version is another, more studiously reported account, but he is not the first to challenge the popular mythology. Way back in 1999, Wypijewski rejected what she called the "quasi-religious characterizations of Matthew's passion, death, and resurrection as patron saint of hate-crime legislation" in favor of what she called "wussitude" -- a culture of "compulsory heterosexuality" that teaches young men how to pass as men, unfeeling, benumbed, primed to cloak any vulnerability in violence.

It was Wypijewski, too, who wondered if Price -- the star witness -- simply thought she was helping out her boyfriend when she told the press that he and Henderson "just wanted to beat [Shepard] up bad enough to teach him a lesson not to come on to straight people." If you thought gay panic was a better defense than a drug-fueled rampage, wouldn't you, perhaps, go with it?

Jimenez is less interested in that kind of social analysis, but what's striking throughout his book is how desperate McKinney is to refute allegations that he is gay or bisexual -- even at the expense of undermining his own case. Whether it was a hate crime, a drug crime, or a combination of the two, it's hard to shake the suspicion that self-hate and a misguided culture of masculinity, which taught McKinney to abhor in himself what Shepard had learned to embrace, was as complicit as anything else in the murder of Matthew Shepard.

That is, of course, a kind of hate crime -- just not as straightforward as the one we've embraced all these years.

The Book of Matt: Hidden Truths about the Murder of Matthew Shephard (Steerforth Press) is published on October 1.