At the height of the riots that erupted 46 years ago at the original Stonewall Inn, Richard Goldstein and his colleagues in the newsroom of The Village Voice were witnesses to history.

"We could see the whole thing," Goldstein, 71, tells The Advocate. "Our windows faced Christopher Street," which was ground zero for the chaos that began with a police bar raid on June 28, 1969.

The journalist, author, and college professor expressed his sympathy to his fellow "straight white guys" in the newsroom for the protesters he called "those people," what his Village Voice colleague Lucian Truscott IV dubbed "the forces of faggotry" in a July 2 article.

"I sure hope those people get their rights," Goldstein recalls saying at the time.

This was a decade before he came out, became America's first widely read rock music critic, and married a man. In 1969, Goldstein was 25 and married to a woman, and didn't even consider himself gay.

"I wasn't faking with my marriage, even though I can say I was always gay. I thought all gay men were rich," he says. "And I'm from the projects: There are no poor gay men, I thought."

Goldstein's new memoir, Another Little Piece of My Heart: My Life of Rock and Revolution in the '60s, recalls his move from the Bronx to Manhattan and how music became a surrogate for what he calls his "hidden homosexual feelings."

"I expressed them not in sex but in words," he says.

At the time, Goldstein and his wife did have a gay roommate, whose life Goldstein now says "was terribly hard."

"He was having lots of sex. I mean, lots. Always having sex, he was -- there was a parade of people! But he didn't have the love he wanted and needed," Goldstein recalls. "We were close, but I couldn't go there, not if I couldn't have love in my life. So I decided men cannot love other men."

But Goldstein says he wasn't self-hating, comparing his experience to the classic queer film The Boys in the Band.

"I decided this would be dangerous," he says of the thought of living openly. And so when his roommate took him inside the original Stonewall Inn, prior to the raid, Goldstein went as an outsider, into one of the few places in the city where gays could slow-dance together.

"What the bar was known for was being permissive to all the gays who couldn't get in to other gay bars," he recalls. "The 'fluffs,' we called them, for wearing fluffy sweaters, you know, mohair. There were drag queens, those who were down-and-out. Gay life was very stratified back then.

"So imagine my reaction when I saw the sign that said, 'Gentlemen Must Face the Bar' [in the event of a police raid]. And they had a red light that would go on if that happened. I thought to myself, Thank God I don't have to live this way."

Goldstein says the social mores of the time, what he called "the system," kept him in the closet. "The system coerced people like me to not explore their gay feelings," and the media of the time reinforced that negative impression.

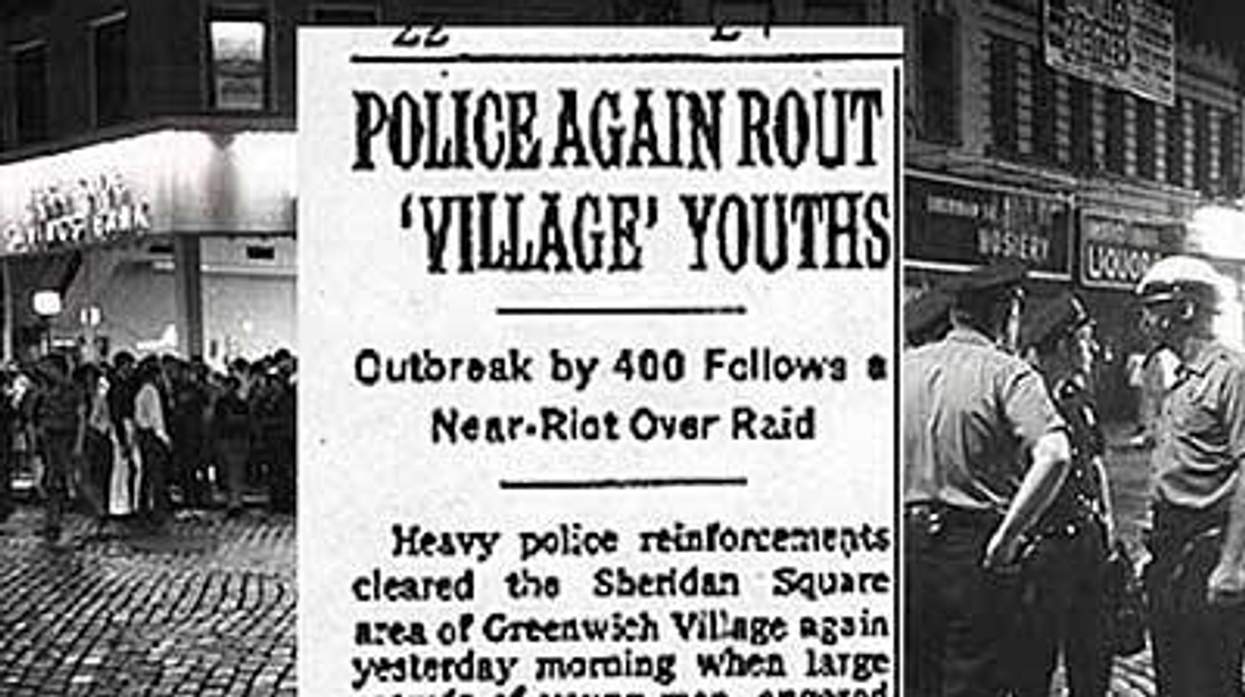

The New York Daily News captured that best with this heinous headline the day after the first clash: "Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad."

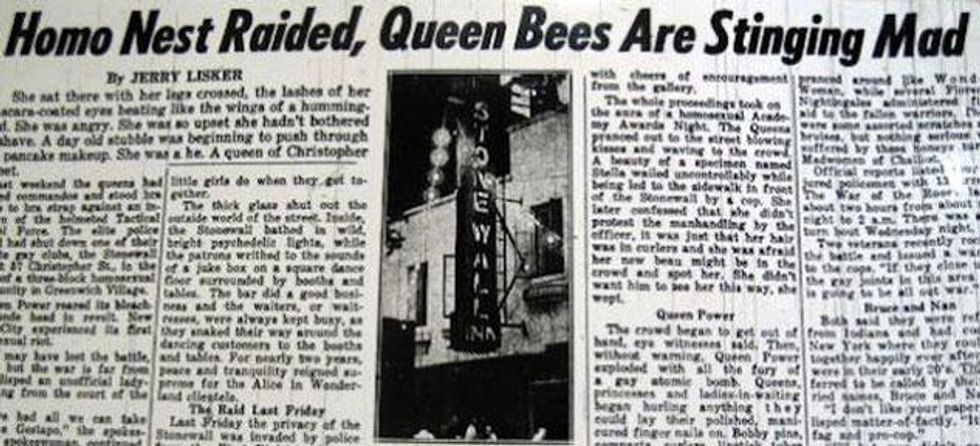

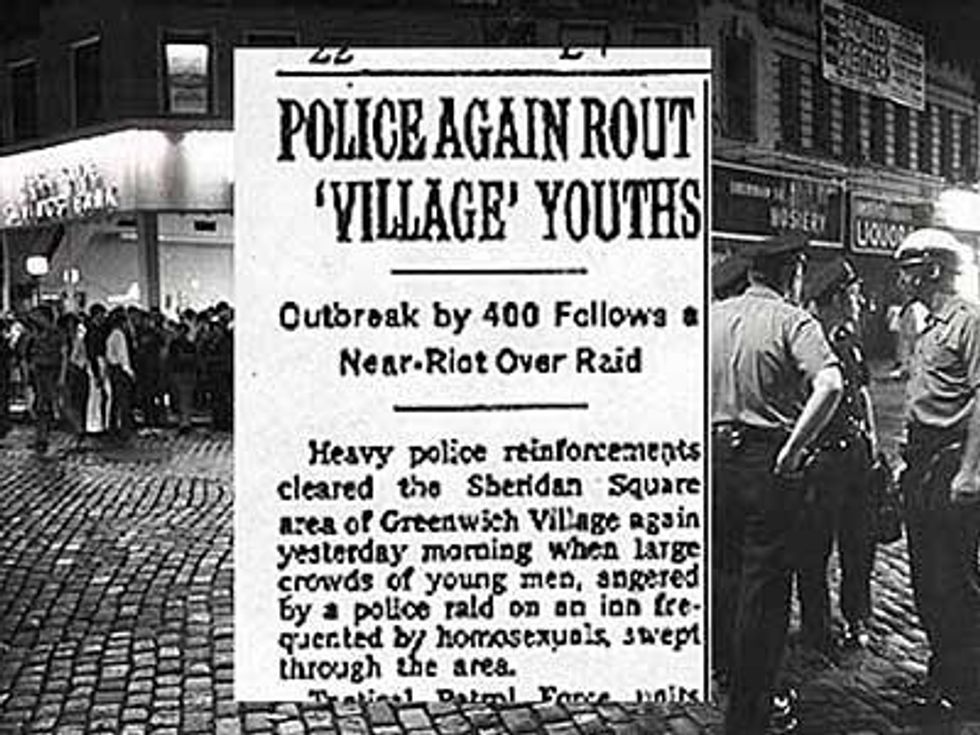

To most Americans who read and watched the news, the protests through July 2, 1969, were an illegal act by an unruly mob of queers, f****ts and cross-dressers. And despite the weekly newspaper's more famous left-leaning reputation -- it became the first employer to offer domestic-partner benefits to its lesbian and gay employees in 1982 -- The Village Voice's coverage was not very positive either.

Author David Carter wrote in his 2004 book Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution that the July 2 edition of the Voice was actually responsible for reigniting passions in the streets surrounding the Stonewall Inn, because gays saw the coverage as disparaging.

In fact, the Voice itself boasted that two articles that appeared on its front page, describing the struggle happening both inside and outside the Stonewall Inn, caused the renewed tensions.

In fact, the Voice itself boasted that two articles that appeared on its front page, describing the struggle happening both inside and outside the Stonewall Inn, caused the renewed tensions.

The late Howard Smith, a Voice reporter, described how he found himself trapped inside the Stonewall with retreating police officers as they came under attack by the crowd. At one point, Smith wrote that he wished he had a gun to defend himself, just like the cops.

Meanwhile, Truscott's reporting on the agitated street scene outside the building invoked every negative stereotype possible. "Limp wrists were forgotten," Truscott wrote, using words such as "f****t" and "faggotry," which enraged gay activists. Anger at the pieces ran so high, rioters marched on the Voice office as well.

"The reporters who volunteered to cover Stonewall were definitely, decidedly, heterosexual," says Goldstein -- and it showed.

What the Voice did do right, according to Goldstein, was lead the way in terms of diversity hiring, calling his old paper "a pioneer of hiring gay journalists beginning in the 1950s. It was the only paper that hired openly gay people."

And that tradition was not limited to sexuality, the onetime executive editor tells The Advocate. "We always hired someone who is writing about what they are living in the scene. For the hippie beat, we hired a homeless hippie who lived part-time in the office. For the punk scene, we hired someone who hung out at CBGB."

Still, says Goldstein, the Voice remained "very homophobic and macho in a conventional, Marxist way."

Change came much more slowly at The New York Times, which not only suppressed its own photographs of the Stonewall riots for nearly four decades but refused for years to cease referring to gays as "homosexuals." In fact, under the leadership of the late A.M. Rosenthal, the title "Ms." was not permissible and "gay" could only be used as a synonym for happy.

Now the Times has become very proactive in LGBT coverage, including same-sex weddings in its society pages and dramatically expanding coverage of transgender issues. But it wasn't until 1993 that the paper ran an article honoring the achievements of LGBT reporters, headlined "Gay Journalists Leading a Revolution," while still using the word that offended so many of them:

"Homosexual journalists, once as hidden in newsrooms as they were in much of America, have become sharply more visible in major news organizations in the last several years and they are helping to change news reports and reporting.

"No one knows how many there are, but journalists at many news organizations now openly identify themselves as being gay. And there is wide agreement that homosexual journalists are bringing about more, and more sophisticated, treatment of gay subjects."

"Those were the days when fact checkers wouldn't accept a gay newspaper to be accurate," says Goldstein, who came out in the pages of the Voice when he was 35, telling his stunned colleagues and readers, "I know what it is like to have sex with men."

Read the controversial 1969 perspective of Howard Smith, the only reporter inside the Stonewall Inn, here.

In fact, the

In fact, the

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes