For 21 years, Susan's Place, an online transgender support network, has granted a lifeline to men, women, and genderqueer folk in every stage of transition.

The site has about 250,000 visitors a month, many of whom use its forums (1.6 million posts and counting), chat rooms, and news feeds to spark friendships with trans people around the world. For the newly transitioning and questioning, Susan's Place is a safe space to navigate the waters of the trans experience.

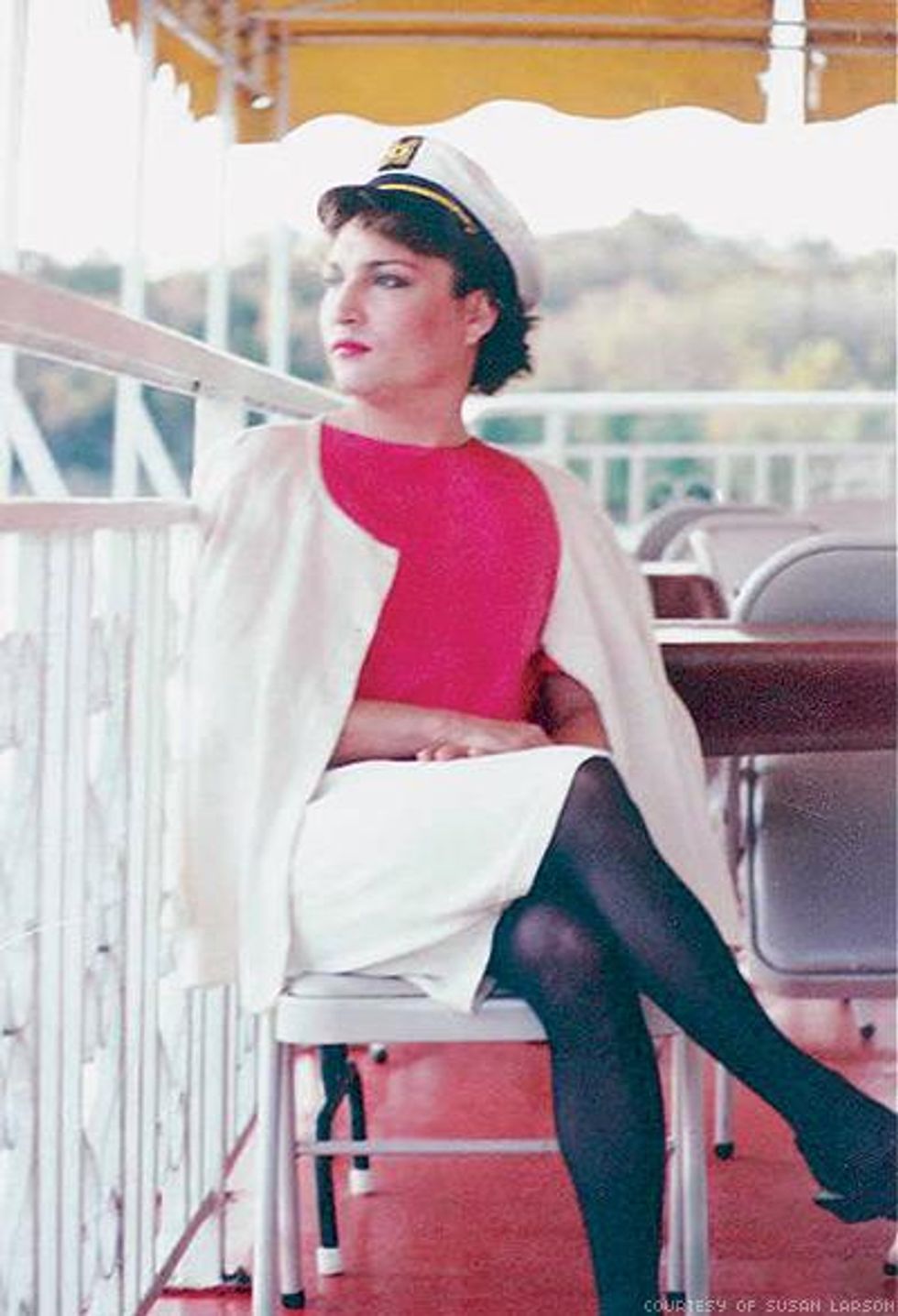

Susan Larson, 45, the affable commander at the helm of this ship, has seen the trans movement grow and metabolize inside her online community. For two decades, she's quietly watched trans people from every corner of the world use her site to make sense of life outside the gender binary. After years of helping strangers embrace their transitions, she's finally moving forward with her own.

"Fear is something every trans person has to overcome," Larson told me. "For a long time, it got the best of me."

Larson has been out to friends, family, and visitors to Susan's Place since the early 1990s but has mostly presented as male in public. The high cost of running Susan's--back-end expenses like high-traffic Web hosting, paired with the sheer amount of time it takes to tend to the site--left Larson with little discretionary income, and the cosmetics, electrolysis, and gender reassignment she longed for were never within reach.

She also dreaded her community's reaction. Larson lives in Clarksville, Tenn., a conservative town nestled on the Kentucky-Tennessee border. As an ultra-active member of her community--Larson has served on town boards and once worked as a local newspaper reporter--she feared strong negative reactions from her neighbors. As it turns out, she was half right.

In many ways, Larson is a quintessential Southern belle. She's loquacious and polite. She doesn't swear. She calls people "sweetheart." On a recent Skype call, Larson showed off the cherry-red nails she got in celebration of becoming "full-time Susan." Those nails, and the sea change they represent, have been a long time coming.

Larson said she's known she was female since she was 3 or 4 years old, but things "really started to crystallize" when she saw a TV ad for Let Me Die a Woman, a documentary-style exploitation film about transsexualism, at age 7.

At 16, Larson dropped out of high school and found work on the Queen of Clarksville, an excursion boat that took tourists on sightseeing cruises along the Cumberland River. As a nighttime security guard, Larson was often alone, and she used the opportunity to dress in women's clothing. In 1994, she started to come out sporadically to close friends and family, and in 2000, she started hormone replacement therapy.

Coming out as transgender has never been a cakewalk (in 2015, at least 23 trans women were murdered in the U.S. alone), but this was a particularly fraught time for northern Tennessee. In 1999, Barry Winchell, a soldier at an army base 13 miles from Clarksville, was beaten to death for dating the now-famous trans activist Calpernia Addams--an incident that made national headlines and shook Larson to her core. She decided to continue dressing androgynously whenever she left the house, covering her growing breasts in an old, ratty coat. Even in the sweltering heat of Tennessee summers, the coat provided a "psychological shield" between Larson and the rest of the world, she said.

For years, she found solace from gender dysphoria through connections made with other trans people in chat rooms and forums. When the Web-based chat on her favorite site, TGForum.com, temporarily shut down in 1995, Larson launched her own version a few months later. That site, the first incarnation of Susan's Place, was a chat room for a fluctuating crowd of 20 to 30 people, she said.

In the years since, Susan's Place has grown into a cultural force to be reckoned with. In 2015, 2.7 million people visited the site, with steady showing from male- and female-identified trans people, cross-dressers, and non-binary folks, according to Larson's metrics. The most active users are older than those on competing trans spaces like Reddit and YouTube, and many have been around since the site's inception, so the sense of mentorship is as strong as the sense of camaraderie. There are strict rules: no "admirers" or fetishists--as Larson explains, "I want Susan's to be a place where you can send a wife, a mother, a daughter, a son, a husband." Also prohibited is any talk of "DIY," the practice of illegally purchasing hormones online without a prescription.

To keep things running smoothly, the site has a rotating staff of about 80 volunteers. Their roles vary: some moderate the forums, others write news items, but all provide outreach to the public. Their audience is a vulnerable one--at last count, the suicide-attempt rate for trans men and women hovered at about 40%--so a large part of every admin's job is to prevent self-harm.

Dr. Cindy Macardle of Melbourne, Australia, a cancer researcher and head forum administrator of Susan's Place, says it's not uncommon for a moderator to stay up all night talking a struggling person off the ledge. Macardle, for her part, has been on both sides of that conversation.

"I found Susan's because I was struggling," she told me. "That's the thing about being transgender--you think you're the only person in the world like you. To find so many people who have exactly the same story is quite affirming. You realize, I'm not sick. I'm not mad. I'm normal."

There's not always a happy ending. Over the years, Susan's Place has mourned both users and administrators. But Macardle said the site offers "utterly remarkable" solidarity and support and that it is indicative of incredible self-sacrifice from Larson. (Macardle has made sizable donations to keep the Susan's Place site alive, according to Larson.)

Larson works on Susan's Place full-time, living off subscriptions and donations to the site. Many months, she said, those funds barely cover her bills. A few years ago, a car accident depleted the savings Larson had set aside for hormone therapy, and she was forced to choose between continuing the site or continuing her transition. It was an easy decision.

"I've received hundreds of emails, letters, and Facebook messages from people saying Susan's saved their lives," Larson said. "The site comes before anything else. Even transition."

In 2013, Bobbie Huthart, a wealthy trans woman living in China, found Susan's Place through a gender therapist. She and Larson quickly became close friends, and when Huthart learned of Larson's financial misfortune, she decided to step in.

Over the 2015 holiday season, Huthart called Larson and said she would fund her gender-confirming surgery at the Preecha Aesthetic Institute in Thailand, where Huthart herself had surgery this January. (Larson's appointment is scheduled for January 2017.) When Larson's requisite shock subsided, she knew it was time to push her public transition forward. She drafted a coming-out letter and, on January 6, posted to Facebook as Susan for the first time:

"I am a transsexual," she wrote. "From my earliest memories, I have always felt a sense of wrongness about myself, my body, and how others interacted with me. I had no name for it, but I felt it nonetheless. As I grew older I realized what it was, and that others did not feel the same way that I did. I was being raised as a boy, but I knew with all my heart that I wasn't one."

It was time to throw out the old, worn-out coat. "I am Susan 100%," she wrote.

In the months following, Larson's neighbors have, of course, taken stock of her changing appearance. Larson is the first transgender person most of

Clarksville has ever met, and her public transition is something of a lesson in a changing world.

The people of Clarksville offer a different kind of lesson. Before Larson came out, she was ready to be a pariah, but the town has handled her transition with compassion and grace. It's the little things: the waitress who compliments her appearance, the wife of a local politician who gave her a "welcome to womanhood" hug, the minister who offered to re-baptize Larson as her "true self."

The big things matter, too. When we last spoke, Larson had just come back from her first post-transition trip to the local pool. "This is the heart of the Bible Belt, so I'm always afraid of what's going to cause a reaction," she said. "But everyone treated me with the utmost courtesy."

Our country has a long way to go in terms of transgender acceptance, and Tennessee is no exception--the state is one of several with legislators backing the so-called bathroom bills that restrict trans people from using facilities that match their identities. But Larson's coming-out story, and the fairy-tale ending that would have been incomprehensible just a few years ago, proves that things are, indeed, changing.

Paul Ritchie, a longtime friend of Larson's, is a shining example of Clarksville's break with the past. Ritchie fully accepted Larson when she came out to him in the '90s, but he admitted that he never fully understood the trans experience until he "officially met Susan" over lunch at the beginning of March.

"When I saw Susan, everything about her was pure joy. She just shines," he said. "There are people that are learning from her how happy she is, and how happy she deserves to be."

For 21 years, Larson has guided trans people to safety, acceptance, and love. Now, she's teaching the rest of us to do the same.