By the time Marichuy Leal Gamino reached a port of entry into the United States, she had already been stabbed in the stomach and legs in what she says was a transphobic attack that occurred along the U.S. border with Mexico near Arizona.

But unlike an estimated 80 percent of migrant women entering the U.S. through its border with Mexico, the now-23-year-old trans woman says she was not raped on her journey to the "Land of the Free."

The rape didn't happen until she found herself locked in a cell with a mentally disturbed man, in a privately operated prison under contract with the Department of Homeland Security's Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. She was awaiting a decision on her request for asylum when she was attacked.

" Transgender women are not safe in detention because they put us in with the men," Gamino told The Advocate during a recent phone interview from her residence in Phoenix. "We don't know when something's going to happen. There are detainees locked up for long periods, sometimes in isolation. People go crazy. That cellmate I had was not all there. He would always talk sexually to me. I told the guards and they did nothing. ... The guard saw him [exposing himself] to me, and they did nothing."

In fact, says Gamino, some guards even facilitated the alleged abuse she experienced in ICE custody.

"There was a unit manager ... who treated detainees so bad that he lost control of the unit and [prison administrators] had to kick him out, because people would scream the minute he walked onto the unit," she said.

Gamino was released from the privately run lock-up in January, but only on bail, and only after an aggressive lobbying campaign by a coalition of groups to raise funds and awareness about the abuse Gamino allegedy suffered. Gamino now counts herself a member of the advocacy groups that pushed for her freedom, working to eliminate private prisons and detention facilities in the U.S.

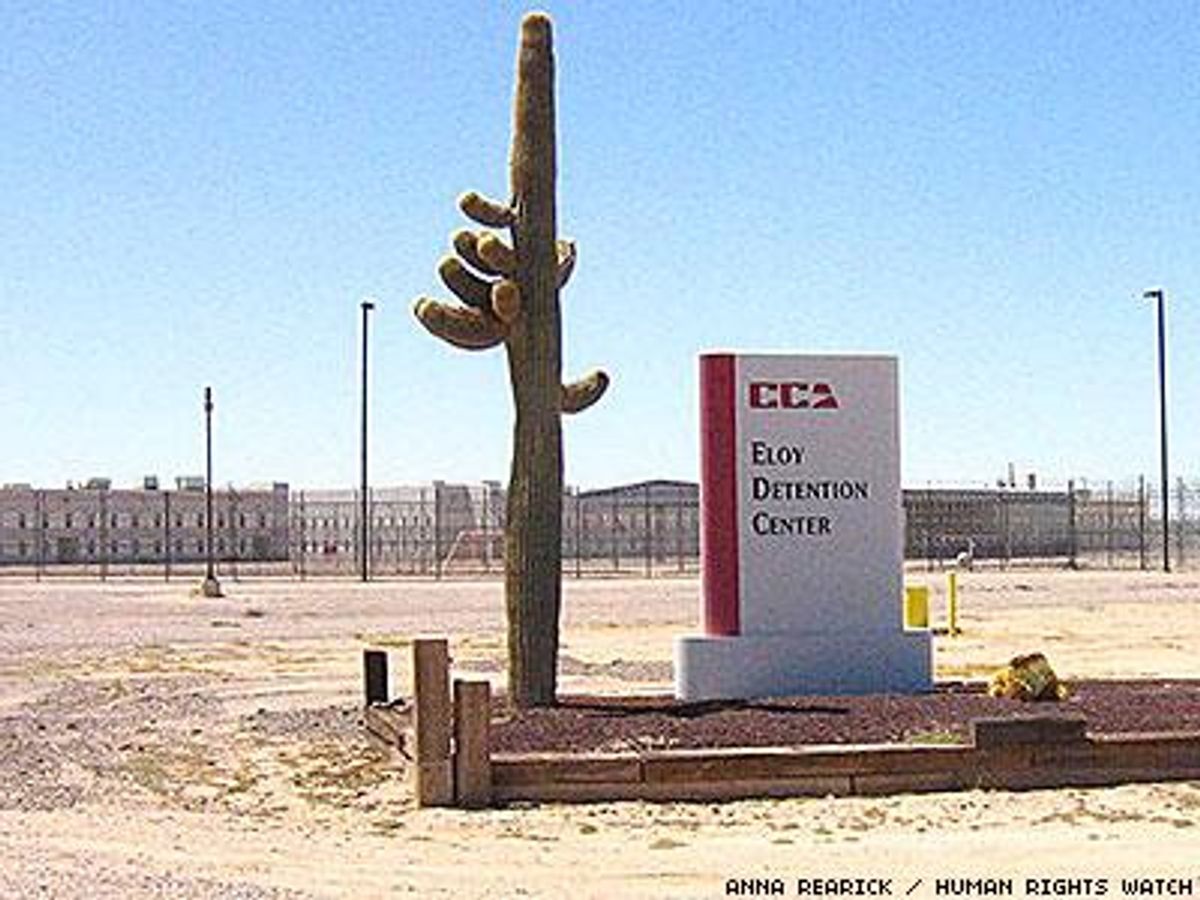

The alleged assault took place last August, while Gamino was held in a privately run men's detention facility in Eloy, Ariz. When she informed facility officials of the rape, Gamino says she was coerced into signing a statement claiming the sexual assault was "consensual."

According to Phoenix TV station KSAZ, the Eloy Police Department is investigating the alleged rape. Prison officials refused to comment; however, ICE officials confirmed that there was an incident that included an initial allegation from Gamino of rape at the hands of her former cellmate.

"U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement is firmly committed to providing for the safety and welfare of all those in its custody," said an ICE spokesperson in a statement provided to The Advocate. "ICE has a strict zero tolerance policy for any kind of abusive or inappropriate behavior in its facilities and takes any allegations of such mistreatment very seriously."

But Gamino says she had previously informed officials that her alleged assailant made derogatory remarks and threatened her with rape before the assault. She further contends those officials took no action to prevent the alleged attack.

After reporting the attack, Gamino was placed in solitary confinement for "protection," according to officials -- though advocates called the move "punishment" for speaking out about her treatment.

Gamino (pictured right) says her time at Eloy was torturous. But the thought of going back to Mexico is even more frightening.

Gamino (pictured right) says her time at Eloy was torturous. But the thought of going back to Mexico is even more frightening.

"Transgender women and other immigrants who are running away from abuse in other countries come asking for asylum, and then they put us in custody where the abuse continues," Gamino said. "It's the same situation. I'll get killed if they make me go back home, to the town where I was in Mexico. And I'll be tortured in a men's facility if ICE takes me into custody again."

As she awaits her asylum hearing, Gamino -- who grew up Arizona after being brought to Phoenix at age 6 -- is cautiously optimistic.

"I feel pretty confident that I will get asylum, but nothing is guaranteed," she said. "My final court date is July 23. I grew up here in the U.S. I want to stay here, because I don't know anything about being from Mexico. I'm from here."

Gamino's troubling experience as an ICE detainee has given the young woman a new purpose in life. She has become an advocate for the rights of other immigrants, detainees, and prisoners as a newly minted detainee-rights coordinator for Phoenix-based Arcoiris Liberation Team.

Arcoiris frequently helps organize marches, demonstrations, and protests, including one held late last month in Phoenix aimed at celebrating the release of Nicoll Hernandez-Polanco, a 24-year-old Guatemalan trans woman who was allegedly sexually abused, then temporarily placed in solitary confinement by officials. Hernandez-Polanco was held for more than six months at an all-male Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center in Florence, Ariz.

In addition to being a celebration of victory in securing the release and granting of asylum for Hernandez-Polanco, the April march in Phoenix was intended to draw attention to dangerous conditions many LGBT people, not just transgender detainees and prisoners, face in all types of law enforcement custody.

A report by Human Rights Watch published in 2001 titled, "No Escape: Male Rape in U.S. Prisons," is often credited with having inspired passage in of the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act. The act called for a sweeping survey of the American penal and detention system to be conducted within two years. But the problem was so complex it took six years before audits of the nation's detention centers began.

The resulting National Prison Rape Commission Report clearly delineated the LGBT population as being particularly vulnerable. "Research on sexual abuse in correctional facilities consistently documents the vulnerability of men and women with non-heterosexual orientations (gay, lesbian, or bisexual) as well as individuals whose sex at birth and current gender identity do not correspond (transgender or intersex)," the report concluded.

The report quotes Scott Long, then-director of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights Program at Human Rights Watch, who told the Commission, "Every day, the lives and the physical integrity of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people are at stake within our prison systems."

According to the report, the "discrimination, hostility, and violence members of these groups often face in American society are amplified in correctional environments and may be expressed by staff, as well as other incarcerated persons."

That sentiment clearly fits the pattern evident in the allegations of both Hernandez-Polanco and Gamino.

A U.S. Department of Justice official who is considered an expert on PREA recently told the Washington Bladethat considerations about population placement, or deciding where to house LGBT inmates, in the era of PREA are just one part of the safe-detention puzzle.

"For example, PREA calls for changes in language that has been used in facilities in the past," DOJ's Laura Brisbin said. "We talk about respectful communications -- how do you do it and still get the kind of behavior you need for conformity in a locked-down situation."

In a recent article, titled "Why Americans Don't Care About Prison Rape," The Nation linked to the story of a man identified only as "Rodney." A gay former prisoner who claims to have been raped in two Louisiana prisons, Rodney told prisoner-rights group Just Detention that in one of the incidents, "a man entered the shower with me and ordered me to face the wall or he would 'break my fucking neck.' This man was literally twice my size and so I faced the wall without question. I felt his hand on me and I tried to move away. He ordered me not to move as he sexually assaulted me. I cried silently."

While the PREA Commission Report makes clear that lesbian, gay, and bisexual detainees and inmates are at risk, it emphasizes the fact that transgender detainees are especially vulnerable to sexual abuse and rape.

The PREA Commission Report lays out the heightened risk factors plainly:

"Male-to-female transgender individuals are at special risk. Dean Spade, founder of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, testified before the Commission that one of his transgender clients was deliberately placed in a cell with a convicted sex offender to be raped. The assaults continued for more than 24 hours, and her injuries were so severe that she had to be hospitalized. Legal cases confirm the targeting of transgender individuals. In 2008, a male officer at the Correctional Treatment Facility in the District of Columbia was convicted of sexually assaulting a transgender individual in the restroom by forcing her to perform fellatio on him."

The underlying problem, notes the report, is housing:

"Like the individual just discussed, most male-to-female transgender individuals who are incarcerated are placed in men's prisons, even if they have undergone surgery or hormone therapies to develop overtly feminine traits. Their obvious gender nonconformity puts them at extremely high risk for abuse."

A Department of Justice audit released last month criticized one of the nation's two largest private corrections contractors for mismanagement of a prison in western Texas that was plagued by unrest, a death, and a riot. The audit cited lack of medical care and sufficient correctional staff as significant problems.

Compiled by the DOJ's inspector general, the audit stopped short of calling for an end to the practice of outsourcing the management and operations of corrections facilities to private companies. But it did recommend greater federal oversight of facilities like the one in which Gamino was housed.

For her part, Gamino says she wants to see an end to the widespread practice of outsourcing corrections contracts to private companies, for state prison or federal immigration detention.

But another report, released in early April by anti-incarceration group Grassroots Leadership, finds that ultimate goal should be the complete removal of for-profit operation of ICE detention centers.

The report, titled Payoff: How Congress Ensures Private Prison Profit with an Immigrant Detention Quota, says private corrections giants enjoy a unique position in terms of being guaranteed a revenue stream via a congressional mandate. The report names GEO Group, which runs the Texas prison named in the DOJ report, and Corrections Corporation of America, the operator of the facility where Gamino alleges she was raped, as key perpetrators of this prison-for-profit situation.

Grassroots Leadership reports that the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act of 2010 includes language that has been interpreted as requiring Immigration and Customs Enforcement to fill 33,400 beds (later increased to 34,000 beds) with detained immigrants on a daily basis.

"The directive would come to be known as the 'immigrant detention quota' or 'bed mandate,'" reads the report. "The immigration detention quota is unprecedented; no other law enforcement agency operates under a detention quota mandated by Congress."

Grassroots Leadership's Payoff report included Gamino's story, beginning with her childhood in Phoenix, where she grew up after being brought from Sinaloa, Mexico, when she was 6 years old.

Grassroots Leadership's report shed light on how Gamino initially came to be in state prison -- then ICE -- custody:

"[Gamino] was sentenced to a year in Arizona State Prison in Yuma for drug charges. 'I was going through a lot of problems with my family because they wouldn't accept me for who I am, a trans woman,' Marichuy said. After serving a year in prison, she was deported to Mexico because of her immigration status.

After being deported, Marichuy was tortured in Nogales, Mexico because of her identity as a transgender woman. She was stabbed and has a scar on her head where she was attacked. She fled to Agua Prieta, Mexico, but her attackers were following her, so she presented herself at the Douglas, Arizona border to seek asylum in the U.S. Rather than encountering safety, she was immediately sent to the CCA-operated Eloy Detention Center in May 2013 where she was placed in a unit with 250 men. She was repeatedly called 'faggot' by the men she was detained with, which the guards ignored. There was no privacy for showers, and Marichuy recounts that the guards and other detained men would watch the trans women while they showered. She and other transgender women would try to put up a curtain when they showered so the guards and other men wouldn't be able to see them, but they were written up for doing so."

The Advocate reached out to Corrections Corporation of America officials at the Eloy Detention Center for comment about Gamino's allegations of abuse and negligence. They referred us to ICE, which provided The Advocate with this written reply:

"The Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General and ICE's Office of Professional Responsibility investigates all allegations of sexual abuse or other misconduct and takes appropriate action -- whether it is pursuing criminal charges or administrative action -- when such allegations are substantiated. Posters displayed in all ICE detention facilities direct detainees how to initiate a formal complaint. ICE meets routinely with nongovernmental organizations and other stakeholders as a part of the agency's detention working groups. As a result of these discussions as well as the agency's overall detention reform efforts, ICE has issued formal guidance to address the care and housing of vulnerable and special needs detainees."

But posters and guidance for vulnerable and special-needs detainees aren't enough, according to Grassroots Leadership. The organization's report included several recommendations to improve the plight of immigrants and others in custody, including elimination of the ICE "bed quota," decreasing dependence upon and ultimately eliminating private prison companies, increasing oversight of and penalties for infractions by companies like CCA and GEO Group, as well as increasing the use of "community-supported" alternatives to detention, especially for immigrants, such as Gamino, who are seeking asylum from abusive situations in their countries of origin.

Grassroot Leadership's report also included a personal message from Gamino, who says she is haunted by the knowledge that while she is out of the "nightmare" of detention at Eloy, women like Greta Soto-Moreno and Margot Corrales-Antunes are still housed with men at the detention facility in Arizona's southern desert.

But ICE officials stand by their record regarding the care of LGBT detainees. In fact, an ICE spokeswoman who The Advocate interviewed for this story said the organization understands there's a case to be made for providing separate accommodations for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender detainees.

Indeed, such segregated detention spaces, sometimes called "pods" in the prison community, are currently being utilized at an Orange County, Calif., jail in Santa Ana. The facility, which is under contract by ICE, has developed what some call a cutting-edge approach to ensuring safety and respect for LGBT detainees, with a specially designed LGBT unit that is not technically considered segregated. Unfortunately, the number of beds is limited, and a detainee may only be sent to ICE's Santa Ana City Jail LGBT Unit when a bed is available and when, on a case-by-case basis, it is determined that the unit is the only safe option for the detainee.

Officials at ICE point to several policies that were adopted beginning in 2009 as part of the agency's Detention Reform Initiative, which they say are intended to protect and better serve LGBTs in detention, as well as the general population.

Under that initiative, the agency has been working to reduce transfers, improve access to counsel and visitation, promote of recreation, improve confinement facilities, ensure quality medical care, protect vulnerable populations, and "carefully circumscribing the proper use of segregation," officials told The Advocate.

Additionally, said ICE, accommodations are sometimes made specifically for LGBT detainees, such as no-cost continuation of hormone treatment for transgender asylum-seekers who were receiving treatment prior to detention.

But all of that doesn't change the harsh reality for LGBT people detained in ICE detention centers and prisons around the country.

Recalling that she often saw guards at Eloy Detention Center pulling the long hair of trans women detained at the privately run facility, Gamino said it's clear that ICE doesn't understand -- or perhaps doesn't care -- why transgender women should not be housed with men.

"It's a no-brainer," she said. "It's about rape -- avoiding the rape of transgender women by not housing us with men."

Gamino (pictured right) says her time at Eloy was torturous. But the thought of going back to Mexico is even more frightening.

Gamino (pictured right) says her time at Eloy was torturous. But the thought of going back to Mexico is even more frightening.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered