Our nation's history is more fully explored in the new acquisition of objects of LGBT significance.

November 12 2014 3:00 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Over the summer, the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, in Washington, D.C., announced the expansion of its LGBT collection. "As cultural sensitivities and politics have changed," curator Katherine Ott says, "now seemed like an opportune time to more aggressively, directly, and openly collect LGBT materials."

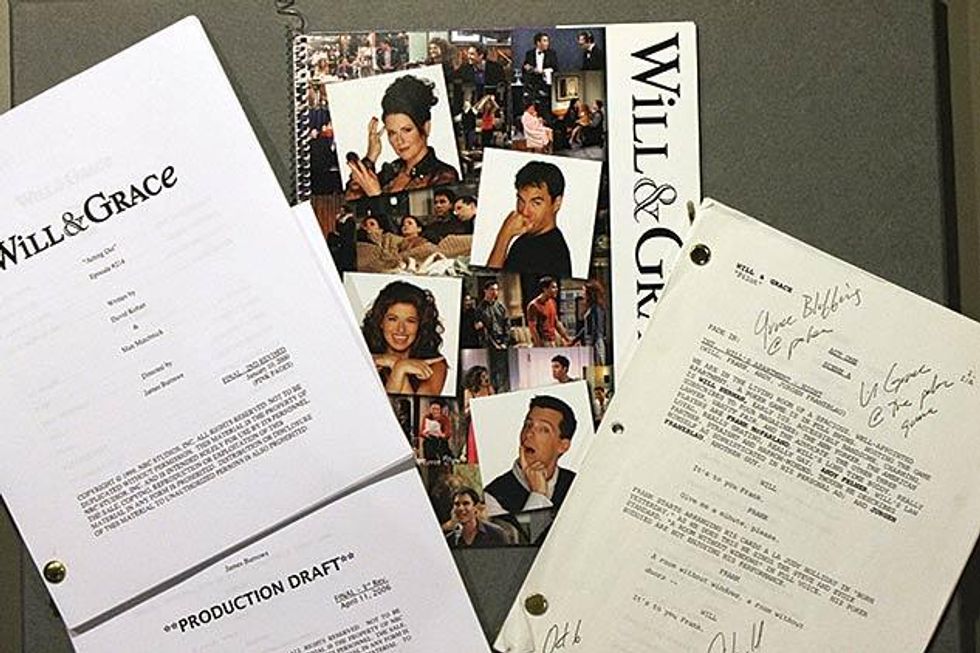

Dating back to the 19th century, the archive includes historical treasures across several disciplines, including medicine and science, political history, culture and the arts, and the armed forces. Standout items include a tennis racket from transgender maverick Renee Richards, who famously won a New York Supreme Court case against the United States Tennis Association, ensuring that she and other trans players would be allowed to compete as their reassigned sex; protest signs from activist Frank Kameny, the co-founder, in 1961, of D.C.'s Mattachine Society, a gay advocacy group; the original transgender pride flag, designed by trans woman Monica Helms in 1999; a tennis dress worn by Grand Slam superstar Billie Jean King; and memorabilia from the set of Will and Grace, the groundbreaking TV show that helped bring gay awareness to households across the nation.

At right: The original transgender pride flag and buttons

The collection also contains darker memories of LGBT history: documents from the military's "don't ask, don't tell" era, HIV- and AIDS-related medical equipment and medications, even a copy of The Anita Bryant Story: The Survival of Our Nation's Families and the Threat of Militant Homosexuality and ephemera from the virulent homophobe's antigay campaign.

"The grand mission of the Smithsonian is the increase and diffusion of knowledge," Ott explains, noting that the LGBT collection reflects that objective. "Pick any topic in our nation's past and there's a gender and sexuality aspect to it, so these materials enable us to create a more accurate and balanced history of the United States."

It remains an open question, however, whether this noble precept will apply to controversial content. In 2010, the Smithsonian provoked the ire of queer activists when it kowtowed to conservative pressure to remove an exhibition clip of gay artist David Wojnarowicz's "A Fire in My Belly," in which ants briefly crawl over a crucifix. Whether Ott and her colleagues will exclude inflammatory historical artifacts under political duress remains to be seen, but it's less likely four years later. "A lot has changed since then," Ott muses, "so I hope it would play out differently today."

"As a historian," she adds, "my professional responsibility is to document what people do and say, even if it makes me uncomfortable."

Ott wouldn't discuss works the museum is currently in talks to acquire, but shared her areas of interest: "It's a combination of media events and personalities that we all know about: Stonewall, the Compton's Cafeteria riot, Bowers v. Hardwick, Liberace, Rock Hudson. Oh, yeah, and I want to collect John Waters's mustache!"

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes