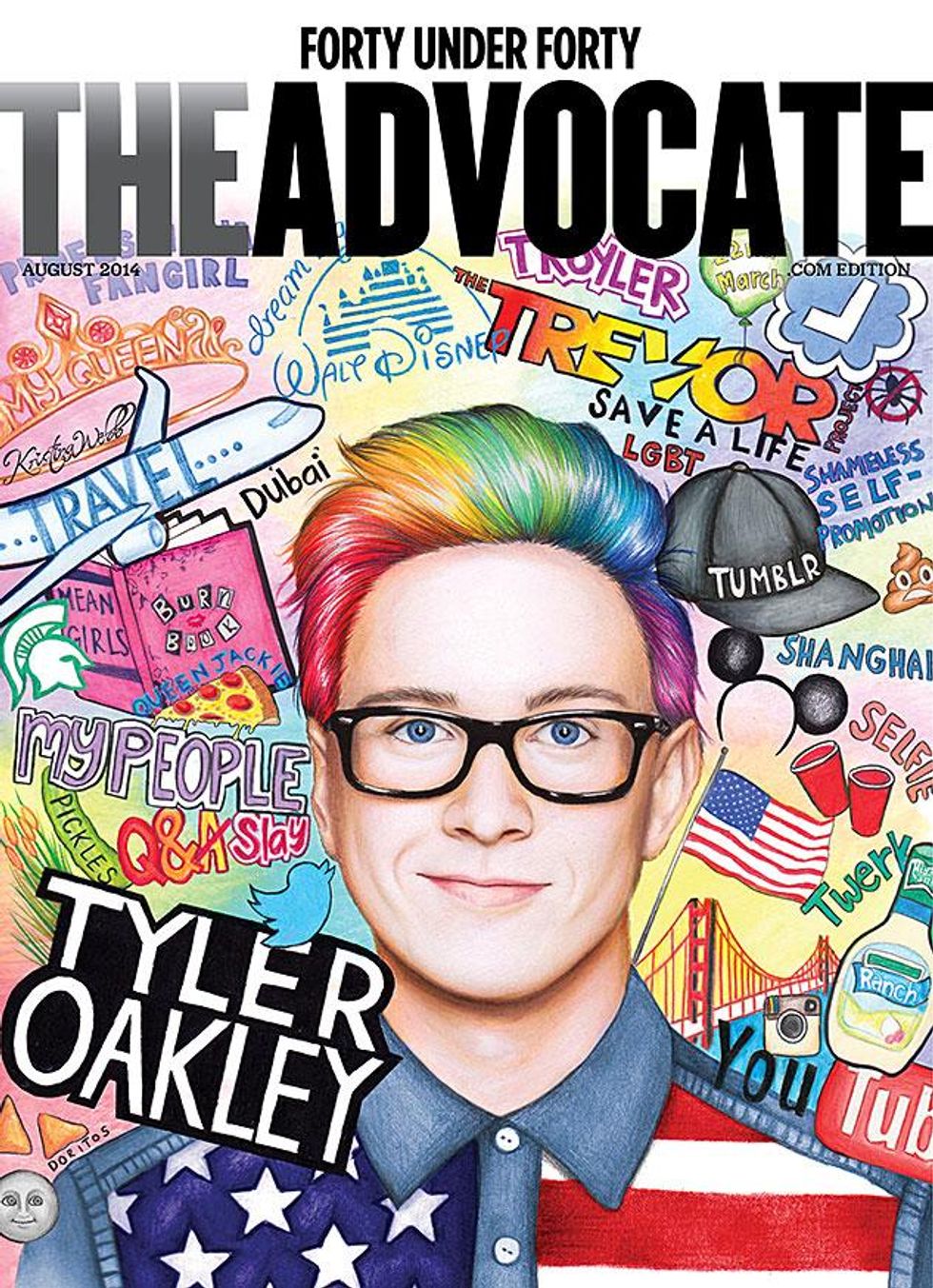

Editor's Note: Artist Kristina Webb is one of the 18-year-old, straight women who are big fans of Tyler Oakley. We noticed a piece of fan art on her Instagram account and got in contact to create a version for our cover. Contact Webb on Twitter and on Instagram to let her know you like it as much as we do.

Editor's Note: Artist Kristina Webb is one of the 18-year-old, straight women who are big fans of Tyler Oakley. We noticed a piece of fan art on her Instagram account and got in contact to create a version for our cover. Contact Webb on Twitter and on Instagram to let her know you like it as much as we do.

-----

Before YouTube launched in 2005, or before Google began helping us search for things in 1998, kids could go through middle school and high school without meeting anyone openly gay. But it still happens, even with all this technology.

YouTuber

Tyler Oakley calls it "mind-blowing" to get messages telling him: "You were the first gay person that I ever saw."

"To have that kind of potential of influence is kind of like awakening," he says, "because this experience that they're having watching me could be really detrimental or really good for how they view the gay community or what the gay community can do."

Oakley posted his first video in 2007 as a way of keeping in touch with far-flung friends during college. That might explain the genesis of his intimate style, which can make you feel like you know Oakley. He's your friend.

That's what is so hard to explain to anyone who didn't grow up in the Tyler Oakley generation, who don't understand his success, or who dismiss the 25-year-old's social media following as unimportant. By now it's trite to point out, but the hallway isn't the only place where friends meet and talk in this century. Friends might be on Twitter or sharing photos on Instagram and videos on YouTube. Mixed in a lot of those feeds you'll find Oakley. He has more than 2.7 million followers on Twitter, 2.1 million on Instagram, and 4.8 million subscribers on YouTube.

Can you imagine growing up with an openly gay friend, one who was the most popular kid in school? Still, Oakley's greatest impact is actually on straight people. Like a lot of YouTubers, Oakley's audience is dominated by young girls, ages 13 to 18. As LGBT people, we should be cheering Oakley's success for what it means about the world to come. In the future, everyone grew up with a gay friend.

When political activists strategize about how to win marriage equality campaigns at the ballot box, one thing they talk about is the power of knowing someone gay in your life. Pew Research in 2013

found that 28 percent of people who support marriage equality said they had changed their minds on it. Then Pew Research followed up and asked why they'd changed their opinion, and the top answer came from a third of people who attributed it to knowing someone who is gay.

Will & Grace is often hailed for opening minds about what it means to be gay. Vice President Biden credited it in part with helping advance marriage equality nationwide. But movies and television can take us only so far. Usually one to dwell on the bright side, Oakley still intoned some disappointment with the way mainstream entertainment makes being LGBT "a central plotline." The bigger the character, the more important it is that they're gay. No so on YouTube.

"It's not all about me being gay," Oakley says, explaining why he's picked up so much traction. "It's kind of like an underlying theme for me," he explains, describing gay life as "sprinkled throughout the videos."

But don't compare what Oakley does to reality television, which he says has perhaps the best LGBT representation but "encourages plot lines that will have the most drama or they'll have the most reactions, and sometimes I guess that's maybe kinda exaggerating the stereotypes that exist to kind of get the ratings."

Oakley, who has used his channel to raise hundreds of thousands for The Trevor Project, looks to the likes of Ellen DeGeneres as a model. "She embodies what I want my experience to be and my influence to be, where it's a positive one, it's a happy one, it's not something about the bad parts of life or the downsides of a lot of things. She's using her influence for good, and everyone knows who she is, what she stands for, and that she is a lesbian."

But YouTube's power to introduce the masses to everyday gay people is also limited. For whatever reason, young white gay men are more widely known on YouTube than people of color or women who are LGBT. Frustration comes, Oakley says, when "sometimes people are put up on a pedestal and you don't relate to that -- but that's who you're told you should relate to because that's your representative in the community."

If Oakley really is a young girl's only gay friend, or really is the first gay person a kid has ever met, he can't represent the experience of every LGBT person. "When there's not a lot of people representing a community," Oakley warns, "I think sometimes people might resent the people who might not fit what they relate to."

Oakley says people "want better and more accurate representations for themselves," and that YouTube has the potential to help. He makes a conscious effort to lend the microphone of his own channel to the likes of Kingsley (a young gay black man whose amassed nearly 3 million subscribers) and Miles Jai ("an amazing YouTuber who is really challenging a lot of gender stereotypes").

Watch out for Oakley's next moves. He dreams about finding ways to raise up the next generation of YouTube talents, acting as a sort of producer instead of host.

"If there's one thing that I could have everyone know, it's that I'm just trying to be my best person, and that in no way do I think that I am 'the voice' of anything, that I'm just trying to be a voice and show people that they can also be a voice."

Editor's Note: Artist Kristina Webb is one of the 18-year-old, straight women who are big fans of Tyler Oakley. We noticed a piece of fan art on her Instagram account and got in contact to create a version for our cover. Contact Webb on

Editor's Note: Artist Kristina Webb is one of the 18-year-old, straight women who are big fans of Tyler Oakley. We noticed a piece of fan art on her Instagram account and got in contact to create a version for our cover. Contact Webb on