LGBT visibility in the realm of comic books has dramatically evolved since the granddaddy of all superheroes, Superman, first appeared on the cover of Action Comics no. 1 in 1938, and one of the people who has helped that evolution take a giant leap forward this year is 30-year-old writer Steve Orlando.

The bisexual scribe currently pens the adventures of DC Comics' Midnighter, the first gay male superhero to headline a series from a mainstream publisher, and Orlando is breaking new ground by refusing to pull any punches when it comes to depicting the character kicking ass, or getting it.

"In the day-to-day world we want to be treated like everyone else, we want to be treated equally," he recently told Out. "So when it comes to what goes into the book I approach it the same way as if I were writing Grayson or Green Arrow. Those characters, the playboys, kill it in the bedroom and so does Midnighter. We give him just as much screen time for that and relationships as those characters because we want him to stand toe-to-toe with them. The way to do that is to show that he doesn't need special treatment and we don't need to fetishize anything."

The general growth of "confidence in queer storytelling" is something Orlando believes has helped push LGBT acceptance forward faster than a speeding bullet - both in entertainment and reality. He is at the forefront of a new wave of storytellers unapologetically crafting tales with a variety of queer characters, giving LGBT people new heroes with wider appeal as well as providing straight readers with images of a queer people that upend stereotypes.

"Midnighter is not a book that has any shame or any type of bashfulness about having a gay male character, but it's about more than that," he says. "It's about the sum total of his characterization. I think people respond to that. So I think you are seeing more queer representation, not just in comics, but in the media. That's pushing forward representation because it's not just representation. It's more layered and authentic and that's giving a new face to the community."

He adds, "Having characters portrayed as real people with real problems and real passion, that's what's pushing acceptance forward because it's harder to have biases once you're able to put a human face to it."

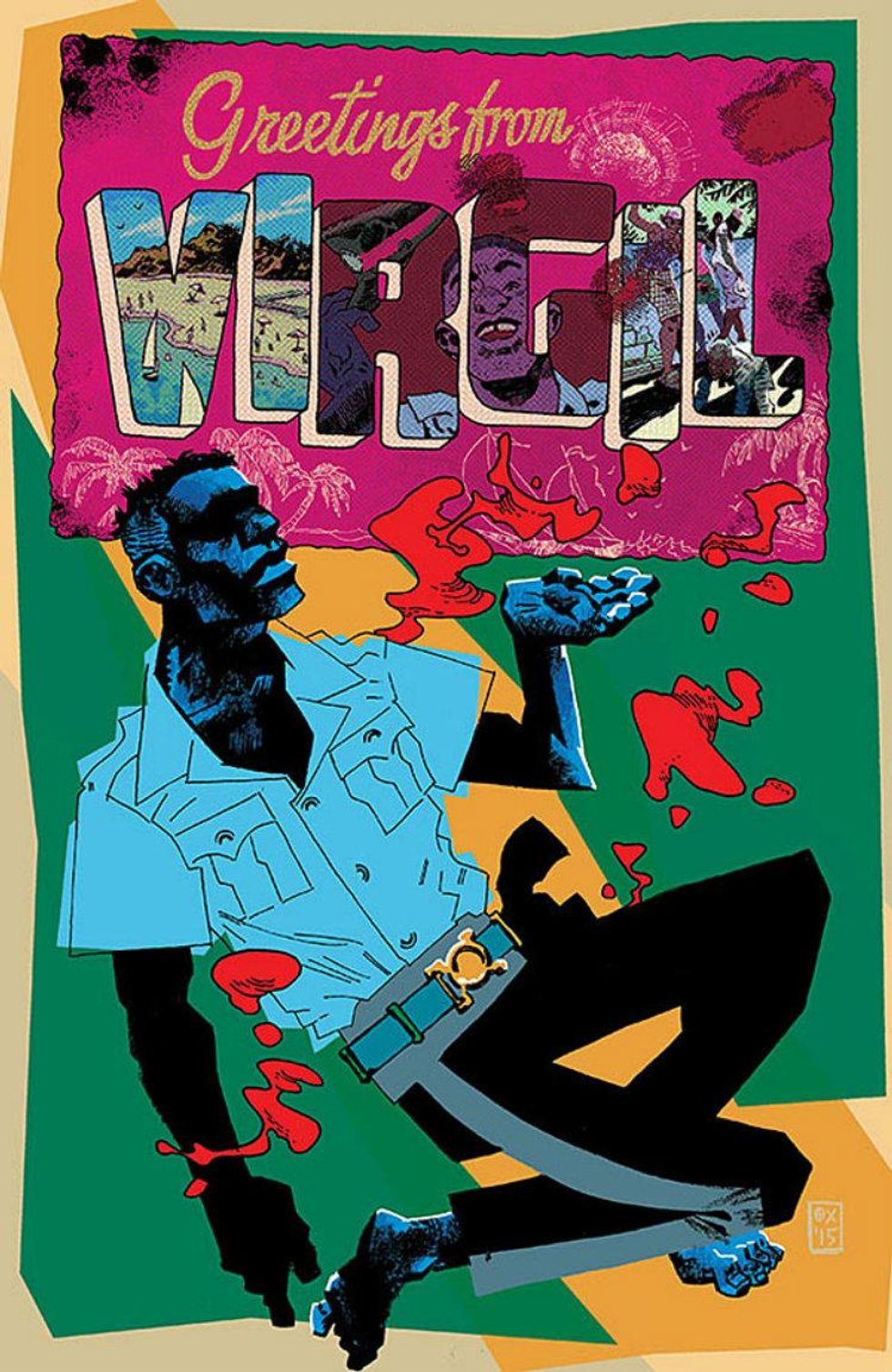

But as happy as Orlando is to be adding to the legacy of one of DC Comics flagship LGBT characters, he's also grateful for the opportunity to break down barriers in another way with his latest independent graphic novel, Virgil, from Image Comics. The story, co-authored by Orlando and Artyom Trakhanov with art by J.D. Faith, follows the tale of gay Jamaican cop, Virgil, who has lived a double life as a closeted gay man on the police force for nearly 30 years. But when his own precinct discovers his sexuality, beats him, publishes his name in the paper, and kidnaps his boyfriend, Virgil vows to fight his way across Jamaica to save his man and get revenge.

For Orlando, the story was a way to not only place a strong gay man of color at the center of an adventure, (a demographic woefully underrepresented in entertainment), but the chance to jumpstart what he hopes will become a new genre in entertainment: queersplotation. "Virgil was always about something I thought people needed, and something I thought was missing in fiction," he says, "The book is framed as this grindhouse revenge, or queersplotaion type revenge story. I wanted the gay and queer community to have our John Shaft or our Sweet Sweetback and all the sort of anger and unrest that goes with that because that's something we're going through."

Orlando also felt placing the story in a country where deadly levels of homophobia exist provided an excellent opportunity to highlight the LGBT civil rights struggle on global scale. "One of the things comics should do is show people things they've never seen before," he says. "In America, we've fought for the right to marry and we're still fighting for equality, but in many other places it is a fight of life and death. So when I looked into communities where this story could take place, the idea came up to place it in Jamaica because it's a place that's often perceived as a paradise, this vacation hotspot, but for gay men there it is not that at all. That contrast between perception and reality was so stark for me that it was something I wanted to show people."

In addition to waking up some members of the LGBT community who may be unaware of the dire situation queer people face in other places around the world, Orlando hopes stories like Virgil can also highlight the commonalities we all share. "There are so many things in Virgil that are universal, like we all want to protect the ones we love," he says. "Some readers aren't going to be Jamaican, or gay, but everyone can understand that primal need to protect those that we love. So stories like this bring people together in that primal universality."

In addition to waking up some members of the LGBT community who may be unaware of the dire situation queer people face in other places around the world, Orlando hopes stories like Virgil can also highlight the commonalities we all share. "There are so many things in Virgil that are universal, like we all want to protect the ones we love," he says. "Some readers aren't going to be Jamaican, or gay, but everyone can understand that primal need to protect those that we love. So stories like this bring people together in that primal universality."

Nevertheless, being an LGBT trailblazer doesn't happen without ending up on the receiving end of a few hard knocks along the way. Writing ultra-violent stories with gay men at their center has earned Orlando criticism from some LGBT readers who worry about the messages comics like Midnighter and Virgil send. Orlando brushes them off, pointing out that what's needed is a wider range of characters from across the LGBT spectrum and queer heroes who embrace violence are needed as much as do-gooders who adhere to that classic superhero moral code.

"It's supposed to be cathartic because we can't go and do all these things we want to do to our oppressors and aggressors," he says. "It's not legal, it's not safe, or perhaps it's not morally sound. Take your pick, but that's what fiction can do. It can be a release for us."

Despite the occasional criticism, Orlando has seen firsthand the positive impact seeing such gay characters has had on readers, and he has no intention of backing down any time soon.

"One of my favorite things since I began writing Midnighter is hearing from people who tell me it gave them something that helped show gay men don't have to be one type of thing," he says. "That's the work that comics should do, because everyone should have that Peter Parker moment where they read about a character and say, 'That character is just like me in some ways. So maybe my life is fantastic. Maybe my life can be mythical.'"

In addition to waking up some members of the LGBT community who may be unaware of the dire situation queer people face in other places around the world, Orlando hopes stories like Virgil can also highlight the commonalities we all share. "There are so many things in Virgil that are universal, like we all want to protect the ones we love," he says. "Some readers aren't going to be Jamaican, or gay, but everyone can understand that primal need to protect those that we love. So stories like this bring people together in that primal universality."

In addition to waking up some members of the LGBT community who may be unaware of the dire situation queer people face in other places around the world, Orlando hopes stories like Virgil can also highlight the commonalities we all share. "There are so many things in Virgil that are universal, like we all want to protect the ones we love," he says. "Some readers aren't going to be Jamaican, or gay, but everyone can understand that primal need to protect those that we love. So stories like this bring people together in that primal universality."