CONTACTAbout UsCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Equal Entertainment LLC.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

We need your help

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

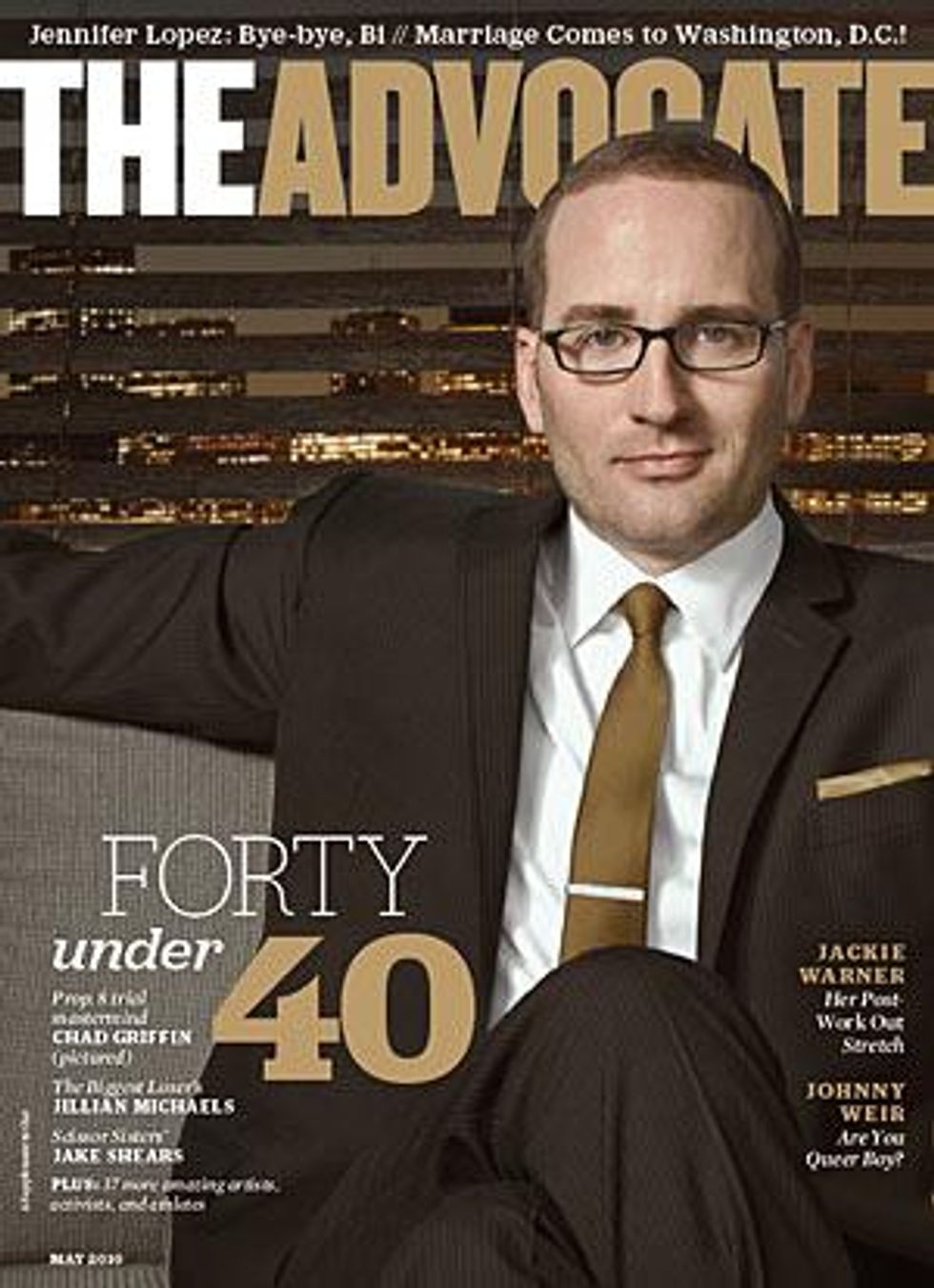

POLITICAL STRATEGIST 36 / LOS ANGELES

The Hunter Allen trail northwest of Los Angeles is the sort of low-impact hike suited for an elderly couple or a birder in search of house wrens and red-tailed hawks circling above--up to a point, that is. About a quarter of a mile in, the path veers up a barren ridge toward a series of high-ceilinged caves. It's a steep ascent but one rewarded by a sweeping vista in a break at the summit. From here, decades' worth of Southern California land-use battles are distilled into a singular view. To the west, 500-year-old oak trees, rolling hills rendered green by spring rains, birdsong; to the east, the San Fernando Valley, America's prototype for suburban sprawl, now home to 1.8 million people.

Chad Griffin snaps a few shots of the landscape with the Leica D-Lux 3 camera he brought strapped over his shoulder in a brown leather case. It's one of the few occasions I've seen him dressed in something other than a suit and tie. As a political strategist--one who cut his teeth barely out of high school as a member of the Clinton administration communications team--this view is one of his proudest achievements. Griffin was instrumental in saving 4.7 square miles of wilderness, a critical watershed leading to Malibu's Surfrider Beach 15 miles due south, from development by its then-owner, Seattle-based Washington Mutual Inc. Before Griffin's efforts, the campaign to preserve the land ran on an earnest, save-our-environment platform. Griffin flipped that messaging on its head and appealed to more base concerns for valley residents, namely increased traffic. Washington Mutual, battered by unprecedented bad press, capitulated and sold the land to the state in 2003.

"In politics it's rare that you work on something so tangible," Griffin says. "You can elect someone, they get into office, they may or may not vote the way you want them to, and they often go to Washington and sell out. But to have something like this, these 3,000 acres of preserved land that you can hike--it's kind of the idea of once you have gay marriage, you will actually see couples come together, get married, have kids. I prefer tangibility."

The trail's namesake, Hunter Allen, was a friend and employee of Griffin's during the fight to save this land, now known as Upper Las Virgenes Canyon Open Space Preserve. "Hunter was insanely smart," he recalls of the young man who ultimately committed suicide after struggling with a crystal methamphetamine addiction that began when he was a teenager. Griffin is polished and passionate when discussing marriage equality and other gay rights issues, but here his tone is exposed, unrehearsed. "He was out. I was closeted--far from out. His own story of coming out always inspired me. I didn't know that he knew that I was gay, but he clearly did. I'm not even sure I really knew then."

Click here to read the rest of the Forty Under 40 profiles.

Chances are you've never heard of Chad Griffin, but this Arkansas native

who now lives in Los Angeles has spent the past year of his life trying

to make a critical change in the way you're able to live yours. This

time, it's not an environmental cause he's championing. It's Perry v.

Schwarzenegger, the federal challenge to California's Proposition

8, the ballot initiative that repealed same-sex marriage rights. (The

case had yet to be decided at the district level as of press time and is

more than a year away from what is expected to be an ultimate ruling by

the U.S. Supreme Court.)

In Perry, Griffin masterminded

the legal team--a ripped-from-the-headlines combination of Ted Olson, a

former solicitor general under George W. Bush, and David Boies, Olson's

legal adversary in Bush v. Gore. He launched the American

Foundation for Equal Rights to help foot the bills that are accompanying

the legal challenge. The organization didn't exist a year ago. Milk

screenwriter and foundation board member Dustin Lance Black only hinted

at an early iteration of the group in this magazine's previous "Forty

Under 40" issue, and it remains a small operation, with one full-time

staff member and a board that includes Kristina Schake, Griffin's

business partner in the communications and consulting firm

Griffin|Schake, and director Rob Reiner, who tapped Griffin in the Las

Virgenes campaign and has worked with him on early-education causes.

Aesthetically, the foundation's website is nearly indistinguishable

from, say, the Tea Party movement's site: no rainbow hues, no equality

symbols, just American flags--something Griffin was adamant about.

"That's my flag too. That's the LGBT community's flag as much as any

other group," he says. "We aren't some different class of people that

wants some unique right."

Mainstreaming the marriage cause,

whether it's through the use of patriotic symbols or by tapping an

erstwhile conservative attorney with a formidable Supreme Court record,

is what makes Griffin's work so effective, says Paul Begala, a CNN

political commentator and former Clinton aide who met Griffin in the

West Wing and has since worked with him on political campaigns. "With

Ted Olson, I carry real grudges. But Chad has this capacity to set aside

that and only focus on what is absolutely central to winning," Begala

says. "He has brains but also roots. He grew up with people who are

concerned about the issues. He's not dismissive of their views, and he's

willing to engage. Many people who are true believers can't bear the

thought of engaging with their enemy."

Griffin was in his element at the Perry trial. Each day he sat in a San Francisco courtroom next to the plaintiffs, Jeff Zarrillo and Paul Katami from Burbank and Kristin Perry and Sandy Stier from Berkeley. ("They're the real heroes in all of this, who have been willing to be the public face," Griffin says.) At daily press conferences he stood up front but out of frame, his back against a white wall, as lead attorneys Olson and Boies made their case--that the denial of marriage rights to same-sex couples is without basis and harms a vulnerable minority--to the American public. Even though the Supreme Court blocked any broadcast of the court proceedings (Griffin strongly supported the broadcasting), the trial turned out to be the "teachable moment" he and his team anticipated. Never before had the mainstream media addressed the subject so exhaustively.

"This was probably one of the bravest things I've ever seen done," says Enrique Monagas, one of at least nine gay attorneys working on the case (Monagas wed his partner in 2008, prior to Prop. 8's passage). "There was a lot of fear about how the case would be received. But Chad was, and is, incredibly confident, and rightly so."

Griffin lives in a comfortable, mid-century modern house in Los Angeles with vintage paintings yet to be hung on the walls. Mario Testino photo books are stacked near fireplaces along with albums filled with snapshots from his whirlwind two years at the White House. Nineteen when he first started working for Clinton, Griffin is not yet wearing his trademark plastic-frame eyeglasses in any of the pictures. But he's now got about a dozen pairs, laid out neatly on a white hand towel in his master bathroom. "I felt like he was my little brother [at the White House]," Begala says. "I still think of him as a young kid, even though he operates at such a high level."

Griffin wants to get married someday, and he also wants to have kids. But he says both desires are beside the point; Perry is no self-serving endeavor. "When people ask me about that, I often say I don't want to talk about it," he says. "Because it's wrong to say that my motivation is so that I can get married. My motivation is the young kid in Arkansas who I once was, or in Fresno or East Los Angeles--the kids who are told every day by the government that they are second-class citizens. It licenses the hate that you hear and that you see every day. So we'll continue to see high suicide rates among gay teens and hate crimes as long as there is this institutionalized discrimination." The talking point on America's gay youth is a recurring theme. "Yeah," Griffin says, "because it's really all I think about."

This work doesn't mean Griffin sees himself as an activist, even if that's the term commonly preceding his name in countless articles written about the lawsuit. In his mind an activist is someone on the front lines well before Griffin arrives, someone who fights the fight, often in obscurity, years before most others take notice. "They're the ones I respect the most," he says. "The true gift of Prop. 8's passage is that it inspired thousands of activists--gay and straight, young and old--across the country." Using that momentum wisely, however, is what Griffin sees as the real challenge for the movement as a whole. "It's important to remember our audience and not spend too much time talking to ourselves. If we have the same strategy, it speeds up our ability to move people in support of marriage, which then quickly moves our politicians and leaders in line. Let's win this, and then move on to other important things. At the end of the day our goal should be to all be out of business."

The next chapter in Griffin's life is anyone's guess--including his. "As long as I'm challenged and enjoy what I'm doing, I'll keep doing it," he says while snapping one final shot as a rock pigeon swoops past him into the caves below. "But I certainly don't plan on being in politics my entire life. One of these days, who knows when, I could disappear for a few years with my camera."

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Bizarre Epstein files reference to Trump, Putin, and oral sex with ‘Bubba’ draws scrutiny in Congress

November 14 2025 4:08 PM

True

Jeffrey Epstein’s brother says the ‘Bubba’ mentioned in Trump oral sex email is not Bill Clinton

November 16 2025 9:15 AM

True

Watch Now: Pride Today

Latest Stories

Kazakhstan bans so-called LGBTQ+ propaganda

December 30 2025 3:24 PM

Trump administration bans abortions through Department of Veterans Affairs

December 30 2025 11:07 AM

Zohran Mamdani: Save a horse, play a yet-unreleased Kim Petras album

December 30 2025 10:29 AM

How No Kings aims to build 'protest muscle' for the long term

December 30 2025 7:00 AM

Missing Black trans man Danny Siplin found dead in Rochester, New York

December 29 2025 8:45 PM

'Heated Rivalry' season 2: every steamy & romantic moment from the book we can't wait to see

December 29 2025 5:27 PM

Chappell Roan apologizes for praising late Brigitte Bardot: 'very disappointing'

December 29 2025 4:30 PM

RFK Jr.'s HHS investigates Seattle Children's Hospital over youth gender-affirming care

December 29 2025 1:00 PM

Zohran Mamdani claps back after Elon Musk attacks out lesbian FDNY commissioner appointee

December 29 2025 11:42 AM

Trump's gay Kennedy Center president demands $1M from performer who canceled Christmas Eve show

December 29 2025 10:09 AM

What does 2026 have in store for queer folks? Here’s what's written in the stars

December 29 2025 9:00 AM

In 2025, being trans in America means living under conditional citizenship

December 29 2025 6:00 AM

Here are the best shows on and off-Broadway of 2025

December 26 2025 7:00 AM

10 of the sexiest music videos that gagged everyone in 2025

December 25 2025 9:30 AM

Trending stories

Recommended Stories for You

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes