One of California's largest farmers' markets is beneath a freeway in its capital, Sacramento -- Route 50, or the intersection of W and 6th streets, to be exact. As cars whiz by overhead, hundreds of patrons below peruse a cornucopia of offerings -- apples, meats, honey, pastries, rainbow-colored carrots, bottles of olive oil, pearl onions, and more -- which are brought in each Sunday morning from the region's many farms.

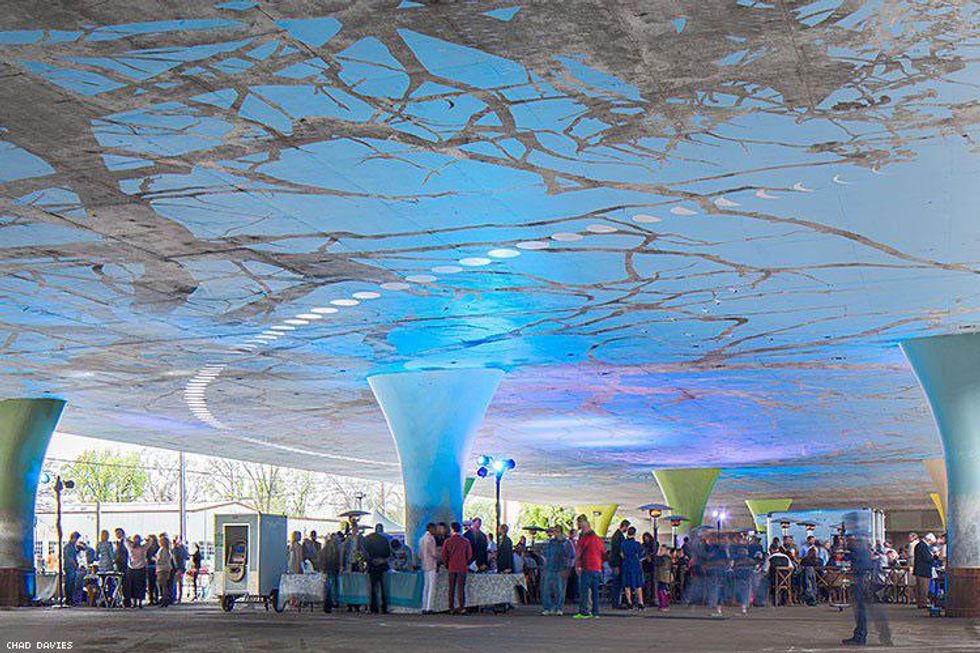

The stretch of cement over the parking lot is far from an eyesore. In fact, it is a work of art. Dubbed the Bright Underbelly, the 75,000-square-foot area is painted with patches of blue, birds in flight, insects, and phases of the moon, which cycles through a lunar year in a circle overhead. Branches of sycamore trees -- live ones once stood in this site -- are outlined in various stages of flowering, a reminder to visitors of the passage of time.

As Allen Ginsberg foreshadowed in his 1955 poem "A Supermarket in California": What peaches and what penumbras!

Poetry aside, the passage of time is one of the key components in the story of how one of California's largest murals -- created by Sofia Lacin and Hennessy Christophel of LC Studio Tutto in collaboration with the California Department of Transportation and Sacramento -- was made.

Completed in March 2016, the project took several years of planning, paperwork, and painting to complete. Its ribbon-cutting, hailed as "a sign of what's possible in Sacramento" by The Sacramento Bee, is also a sign of what's possible in America -- as long as one is provided with inspiration and has patience for the sometimes slow-moving wheels of bureaucratic processes.

"You'd think that just putting paint on cement is the easiest possible thing. But if you're a freeway engineer, it's not," said Tre Borden, the project manager and "placemaker" who first envisioned art where blank cement once stood.

Borden, a gay graduate of Yale University and the University of California, Davis, Graduate School of Management, was struck by inspiration for the project during a student exchange program in Buenos Aires in 2011. In the Palermo neighborhood, he encountered a pedestrian bridge and observed how art had transformed a structure that was "utilitarian into a real community gateway." Borden, a native of Sacramento, imagined how such a tactic could be applied to his own city, which is bordered by blank canvases -- highways and infrastructure just waiting for a creative mind to take action.

A seed was planted. But its flowering took a few seasons. In considering a subject, Borden was drawn to the Downtown Farmers' Market because of what the venue represented. This crossroads of commerce showcased the region's agricultural assets. Sacramento is known as "American's Farm-to-Fork Capital," and its largest market is symbolic of the city's pride in supporting local farms on both dining room tables and restaurants. The venue is also melting pot of the city's diverse inhabitants, which includes everyone from "hipsters" to "rich white ladies" to "people who live in the projects" nearby.

Borden, a fellow in the mayor's office of Sacramento at the time, asked Mayor Kevin Johnson how he might implement such a program. The mayor had no idea. So Borden did his own digging. He learned there were many hurdles to clear. For one, the property was managed by the state, not the city. He engaged with people in the arts community, who told him there was no funding or "no real mechanisms" in place for such a project. The manager of the market thought it was a great idea -- but again, the money wasn't there. In the midst of these obstacles, Borden graduated from business school and took a job at a utility company for about a month before realizing his future wasn't there. He quit. Indeed, he questioned whether he would quit Sacramento as well.

However, certain shifts were happening in the city, California, and the country that would determine Borden's fate -- as well as that of the Bright Underbelly. Sacramento's population was changing. Artists, entrepreneurs, and progressive thinkers were moving to California's capital, in part due to the tech industry driving up rent prices and the cost of living in San Francisco. They found a city welcoming to creative types, where a person or group could make a significant impact in ways that might not be possible in larger cities with more established systems.

Queer transplants might be surprised by the vibrant scene. There's a thriving gayborhood, Lavender Heights, where bars like the Depot, Badlands, Faces, and the Mercantile Saloon draw packed crowds on weekends. Dining options are not only farm-to-fork, they are LGBT-friendly, with mainstays like Mulvaney's B&L hosting many a same-sex wedding party.

The city's progressive policies also help. California has been in the vanguard of climate initiatives and health care, which led Gov. Jerry Brown to declare in Sacramento last month, "California is not turning back, not now, not ever," in response to threats on these issues from the White House. (Borden said some of his liberal political contacts in D.C., mourning the loss of the Obama administration, are looking to Sacramento for new opportunities.) The city's spirit of inclusiveness can also be seen in its sports stadium, the Golden 1 Center, which is one of the first major arenas to have transgender-inclusive restrooms.

Even in 2012, the market was ripe for Borden help launch Flywheel, a creative incubator, which taught business skills to creative minds. Two of Flywheel's participants, Lacin and Christophel -- who would become the pair who designed and executed the Sacramento mural -- expressed their interest in the project to Borden. The wheels began turning once again.

Borden is no artist, but he sees his role of placemaking consultant as a bridge between artists, businesses, and political players. His skills were put to the test in realizing Bright Underbelly. He re-established communication with state operators, including California's freeway operator, Caltrans -- "not the tiniest, most nimble bureaucracy, let me tell you," joked Borden. He received a stroke of luck. Caltrans, as a result of the years-long drought that had impacted California, was seeking ways to beautify spaces without water or vegetation. A partnership with an arts project seemed like the perfect solution, and Borden succeeded in obtaining permission from the state agency. All he needed was the money.

Remarkably, Borden and his small team were able to do the fundraising themselves. Not having traditional sources of money at their disposal, they found other means to reach goals. Since the project supported healthy food, the California Endowment, a health foundation, gifted $50,000. Bright Underbelly was able to leverage this donation to convince small businesses to help match the amount. In total, they raised $150,000 for the project. In doing so, Borden and his team also helped "create a new template, a new model for civic improvements" for others to follow.

However, the fundraising wasn't the end of the story. During this process, Caltrans changed legal representation, which added an additional delay of several months. At points, Borden wondered if he would ever be able to navigate around the red tape.

"There was so many points where it felt like, this is never going to happen," said Borden, who often felt like giving up in the face of bureaucracy.

But after about two years from its project launch in April 2014, Bright Underbelly was completed. It was a victory not just for Borden, Lacin, and Christophel, but for all artists and creative people. The rewards to the city were many. In the short term, visitors to the Farmers' Market now enjoy a beautified space, which in turn attracts more business and neighborhood revitalization. In addition, by showing that something is "possible that people didn't think was possible," said Borden, it inspires others to take action as well.

"The fact that this conversation is happening is part of it," said Borden. "Who knows who will read this article and go, 'Hmm, I didn't know Sacramento was a thing, let me go check that out'? Maybe there will be some bazillionaire who wants some investment opportunity or maybe a really excited gay kid who will check this place out. It's hard to measure, but every little bit definitely contributes."

The delay of Bright Underbelly -- the project was initially only supposed to take six months -- was also a blessing in disguise for Borden. As the gears turned on the mural, he engaged in smaller projects, such as helping to convert a century-old factory into the Warehouse Artist Lofts. The mixed-use facility houses over 200 members of Sacramento's creative community as well as two dozen art installations. These artists are also investments for the city, as their accomplishments will bring more Bright Underbellies into the world.

As a result, Borden has taken new root in the city where he was raised. His work has also taken on new meaning since the election of Donald Trump, which has left many members of vulnerable communities fearful of the future. Looking forward, Borden is excited to be planning projects that are "thinking of those communities that are less out of these conversations, particularly underserved black people, Latino people, gay people, and where this could have the most impact."

Borden argued that Trump, who has threatened to cut federal funding to the arts, should learn that the arts are necessary to making America great. Fostering individual creativity, for example, is a more effective strategy to boosting the economy than bullying and bribing big businesses not to fire U.S. workers.

"Trump ... appeals to a person who is afraid, who doesn't feel they could really have an impact in the community. His solutions obviously gear toward the titans of the world who control all these low-wage jobs in warehouses that are never coming back," said Borden. "I think that if he were savvier and not so craven about his solutions, I think [he should be] telling people how they could empower themselves."

Borden cited cities like Sacramento, Indianapolis, and Detroit, where "you've seen how citizens, when they feel empowered with these new tools, they do things that are really resonant to their own communities, and start businesses that people patronize. That gets more people excited about being in a city, and that becomes its own engine."

"I think that trying to return people to the past is not productive, and it's not reality. It's so irrelevant to what's happening right now," he added.

Despite the pessimism that Trump has expressed over the state of the country -- the president invoked "American carnage" and the "graveyard" of industry in his inaugural speech -- and the despair many LGBT people feel about the new administration, Borden sees the bright side. He is hopeful of what can happen in the face of adversity.

"I have a determinately optimistic view. I think that when such a shocking and almost unbelievable external threat happens, people really start to become active and engaged," he said.

"The exciting part about being in Sacramento is it's still a place where you can change a lot of things you think are wrong. All it takes is someone taking an interest."