Arts & Entertainment

Meet the 20th-Century Lesbian Whose Paintings Lined Over 70 Churches

E. Charlton Fortune was an impressionist painter who loved women on and off the canvas.

August 17 2017 1:02 AM EST

October 31 2024 6:40 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

E. Charlton Fortune was an impressionist painter who loved women on and off the canvas.

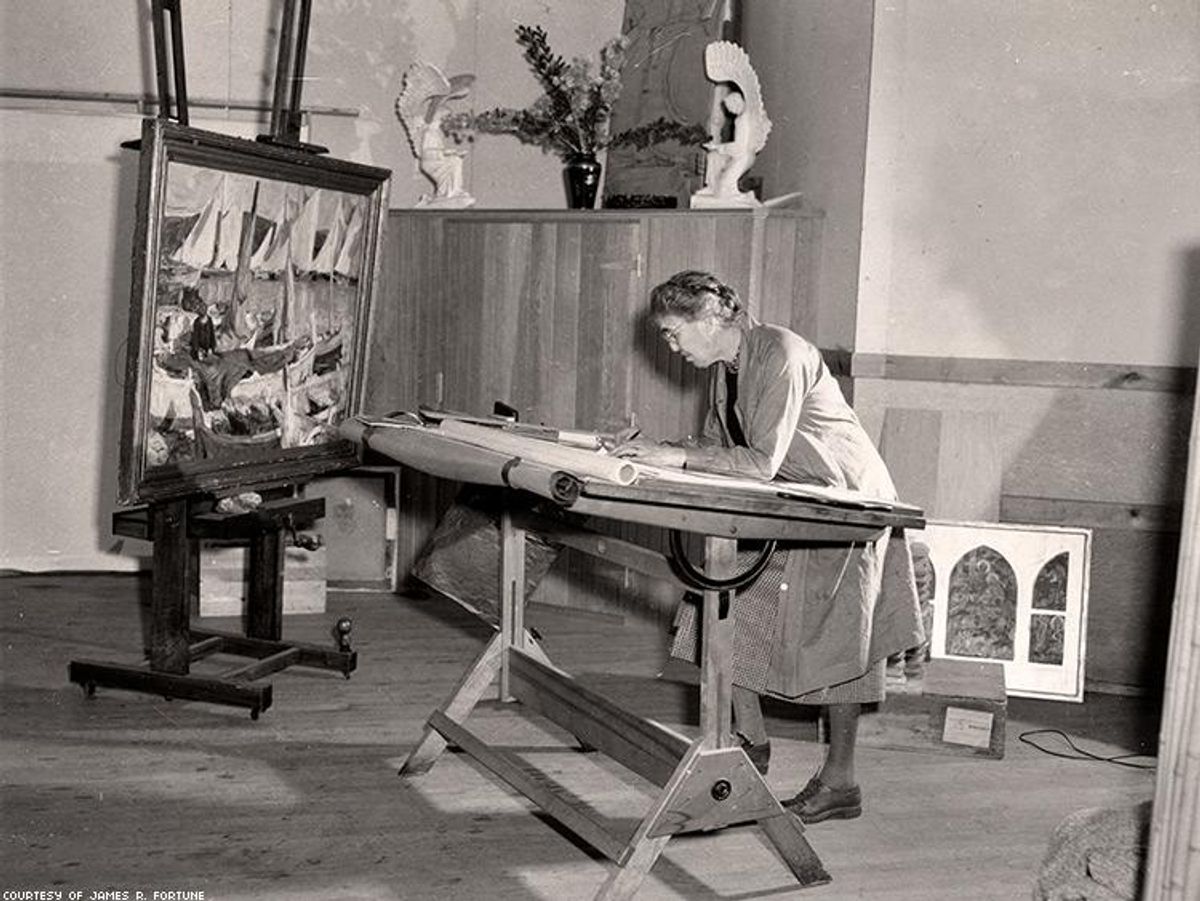

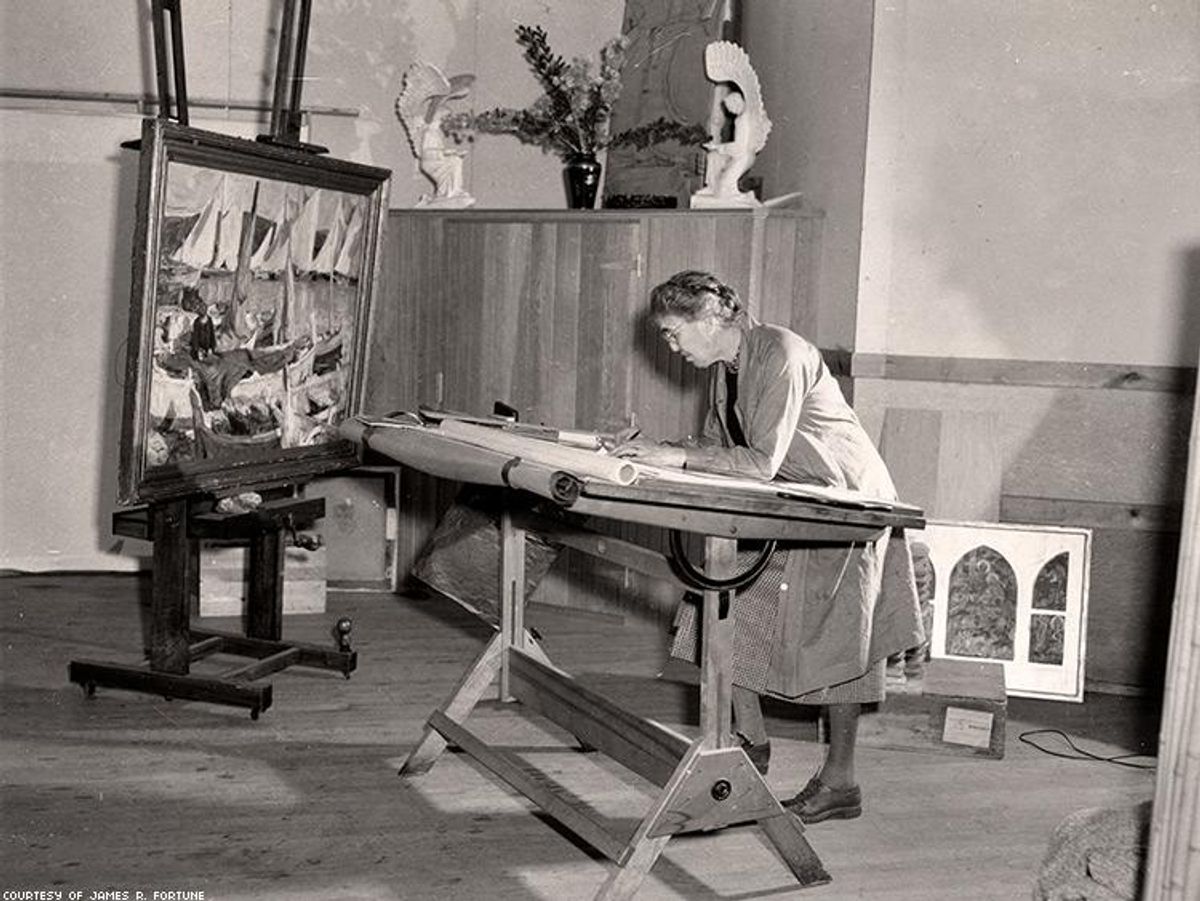

Euphemia Charlton Fortune was one of the most prolific, accomplished, and groundbreaking American painters of the last century. But those familiar with her vibrant depictions of California's countrysides, seascapes, and women knew her as E. Charlton Fortune -- because it was easier. As critics, upon discovering she was a woman, gasped at her gender and expressed astonishment that she "painted like a man," Fortune thought it simpler if she was perceived as one.

In a creative realm where women were ever-present in paintings and scultpures in posed, doll-like perfection, Fortune "got her women off the couch," says Scott Shields, associate director and chief curator of the Crocker Art Museum, which will host one leg of the exhibition of Fortune's work across California, titled "E. Charlton Fortune: The Colorful Spirit." More than 80 of her works will be on display at the Pasadena Museum of California Art, the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, and the Monterey Museum of Art. Along with her technique, the exhibit will feature her commitment "to adventurous women who do."

"Far more than her male colleagues, she made women her focal point," Shields says. "Or at least, or I should say that differently, because a lot of men painted women but they didn't generally paint them doing things. They were sort of lounging around the house, and even some of her fellow women painters -- it would be mothers and children -- but that wasn't really her thing; her women were busy."

(RELATED: 16 Mesmerizing Masterpieces by 20th-Century Lesbian Artist E. Charlton Fortune)

And so was Fortune, who was born in 1885, three and a half decades before female suffrage. After studying at San Francisco's Mark Hopkins Institute of Art, she continued her training at the Art Students League in New York. Independent and happily unmarried, she darted around the world on her bicycle, a new symbol of feminine freedom in an era when women were first striving for the right to travel. Early in her career, she was known for arriving in her trademark corduroy suits, accompanied by leather shoes with shiny buckles. After St. Angela's Church in Pacific Grove, Calif., approached her to design its altarpiece, Fortune founded the Monterey Guild, spearheading a group that furnished America's churches -- the primary hub for art (and well-paying commissions to create it.) Eventually, her work adorned 70 church interiors in 16 states, from Rhode Island to Missouri.

She was immensely successful as an artist. Her work incorporated impressionism and modernism, and explored elements of cubism before even Picasso. Among her honors, Fortune was awarded the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice -- the highest award an artist could receive from the Vatican.

Her work warranted such prestige because of her supposedly masculine artistic style. "Painting like a man was a strong composition, strong colors, strong brushwork, as opposed to sort of delicate colors, more pastels, more subtler, quieter brushwork," Shields notes. "Critics really thought that the way painting was best at that time was in the sort of -- they used the word 'vigorous' a lot, they used the word 'virility' a lot -- that the bolder you could be and the more masculine the paintings could be the better." And Fortune was bold, happy to paint with the boys, and sometimes only with them.

"There were a few other women painters at the time who also got male-gendered accolades along the way," the curator says. "And Fortune undoubtedly knew these ladies, but she didn't really talk about them much. She compared herself more to the male painters of the day."

Except one -- Ethel McAllister, her student, companion, and possibly lover. The two are featured in her small painting Artist(s) at Work, where they sit overlooking a valley. The title does not call them women or lovers or lesbians. Fortune saw herself as an artist first and refused to let anyone think otherwise. But Euphemia loved women. She loved them in her paintings. She loved them in her life.

Somehow, a lesbian (although the term wasn't coined until the 1890s) left her mark on America's art scene, in particular one of the nation's most conservative institutions. It wasn't easy. Many wanted her guild to be disbanded as long as a woman led it.

"She was really going up against a lot of men--male architects, priests, church leaders, all of whom were a little suspicious of a woman doing these things that a woman didn't normally do," Shields explains.

She experienced "as she called it, the idea of this old maid doing these sorts of jobs that women weren't normally allowed to do." At that time, it seemed doing a job was an act of resistance. But E. Charlton Fortune, with a brush in one hand and likely Ethel in another, sure knew how to do it in style.

"E. Charlton Fortune: The Colorful Spirit" will open Sunday at the Pasadena Museum of California Art, where it will be on view through January 7. It will then be at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento from January 28 through April 22 and the Monterey Museum of Art from May 24 through August 27, 2018.