A fashion designer coming out as gay to The Advocate was a huge deal in 1995. Two years later, that designer was murdered.

In Ryan Murphy's retelling of Gianni Versace's murder -- American Crime Story: The Assassination of Gianni Versace -- that 22-year-old Advocate interview comes to life, depictingjournalist Brendan Lemon, who also also broke several other coming out stories for The Advocate, sitting down with Versace.

Read the vintage interview, where Versace discussed his new book, the men in his life, and how Italian Vogue is full of "ugly boys," below:

THE IMAGE MAKER

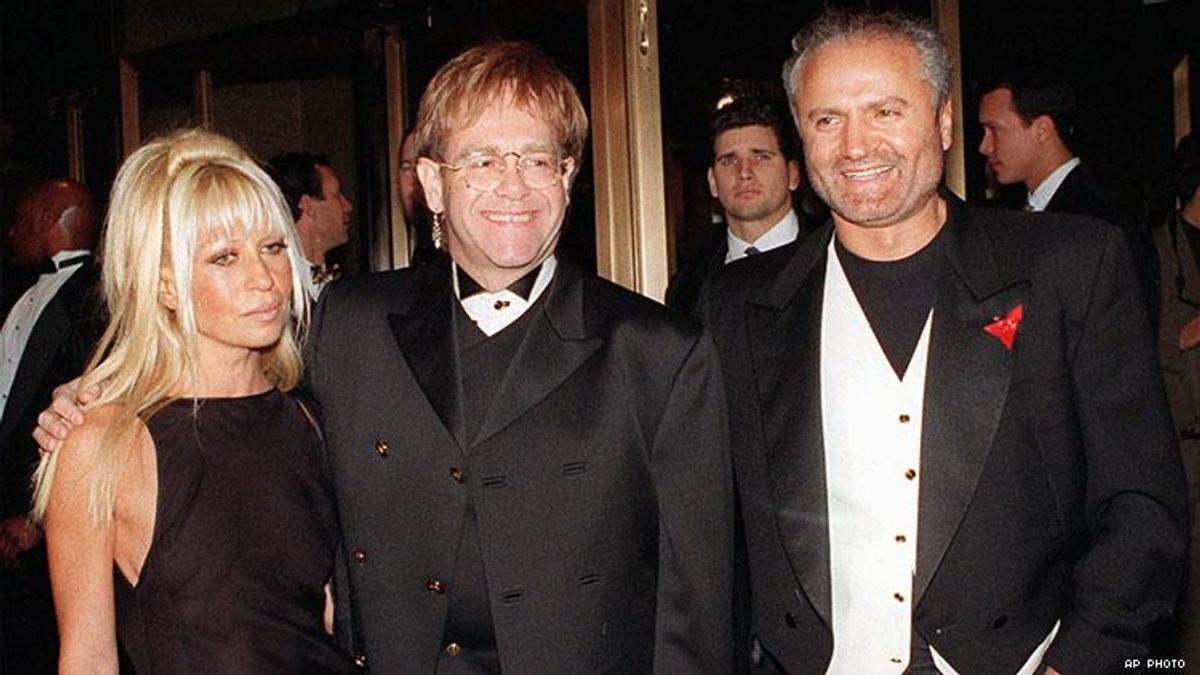

Known for his sexy designs, famous clientele (Elton, Madonna, and Sting) and his homoerotic advertising campaigns, Gianni Versace gives a glimpse into his private world of men. Brendan Lemon reports on the fashion front.

As I walked over to Manhattan's St. Regis hotel to interview the Italian designer Gianni Versace, sexy advertisements for his jeans collection kept staring at me from the streetside phone booths. Ever since the ads began appearing earlier this year, I have had to ration the number of glances I tender in the direction of the posters' muscular, marmoreal figures.

Advertised images of male flesh have not riveted me since the Greek-church shots displaying Calvin Klein's underwear brightened city streets more than a decade ago. Both campaigns, I knew, had been photographed by Bruce Weber. But the association ran deeper than the man behind the camera: As Klein's men embodied a kind of male-oriented fantasy of the '80s, when the buffed male torso seemed inescapably homoerotic, so Versace's beautiful bodies seem to reflect a decade in which a penchant for this kind of advertising has begun to indicate something less automatically gay.

Not that Versace has ever shirked homosexuality. Richard Martin, curator of the Costume Institue at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, says that "there is no question that Versace's own out gay identity has been a part of this work. He is in the tradition of the avant-garde, which means that he is willing to risk a lot. And he doesn't run for cover when his risks provoke outraged response." But, Martin adds, the seemingly avant-garde Versace look -- from the Luke Skywalker designs for the early '80s (he started designing under his own label in 1978 -- to the S/M runway displays of the early '90s -- no longer denotes Versace's true place in the fashion universe. "Five years ago he seemed extreme, in both his men's and his women's clothing," he says, "but now he's a coin of the realm. He reads America in the '90s better than anyone else." And why is that? "Versace," explains fashion jounralist Hal Rubenstein, "understands more completely than any other designer that men are about much more than what they wear to work."

In his new book, Men Without Ties, Versace captures this brave new world of men and thier attire. The latest in a line of deluxe volumes that the 49-year-old designer has produced over the past decade, Men Without Ties features Versace's unfettered approach to menswear, as filtered through the photographs of Weber, Herb Ritts, and Richard Avedon. The vision is entirely fresh, yet it also carries echoes of earlier generation, whose totems -- Picasso, Cocteau, Buster Keaton -- pop up in its pages.

The generational theme is sounded right away on the volume's dedication page. Versace writes, "To the three Antonios of my life: my father, Antonio d'Amico, my nephew." I begin the hotel-suite interview by asking the designer -- a courtly figure with short white hair who lately favors jeans and bright-hued cashmere sweaters -- to say a little about each of the book's dedicatees.

"My father was a handsome man," he replies proudly. "I was afraid of him and also a little in love with him." Versace talks about long boyhood walks the two took together in the southern Italian town of Reggio di Calabria, where he grew up, When he goes on to mention his mother, the tone is more nuanced -- and with reason: It was in her dressmaking atelier that he learned both the craft and the business of fashion.

Versace calls Antonio d'Amico simply "my companion," and for once, the phrase connotes not some Jamesian spinster being trundled around Europe by a niece or some euphemism bestowed by New York Times obituary writers but a genuine term of endearment. D'Amico, who has dark Caesar-cut hair and a warm, flirtatous manner, sits in on the interview and chips in the occassional well-informed comment. As a higher-up in the Versace empire (whose various lines of menswear, womenswear, couture, fragrances, and licensees last year had combined sales of more than $650 million) as well as Versace's intimate for more than a decade, he's well-placed to do so.

It is d'Amico who knows every detail of the designer's peripatetic lifestyle: the constant zigzagging from the business base in Milan to a restored neoclassic villa on Italy's Lake Como to a highly decorative house in Florida (a required stop for first-time South Beach strollers) to a town house on Manhattan's East Side. This last being furnished in gold-and-white Louis XV style and will be completed by year's end, as will a large new Manhattan Versace store.

"Little Antonio, so blond, so macho" is how Versace describes is 4-year-old nephew, the son of his younger brother Santo, who oversees the family's business affairs. Santo's children and the sprightly son and daughter of Santo and Gianni's sister, Donatella, and her American husband, Paul Beck, crop up frequently in the designer's conversation: for someone so relentlessly associated with the trappings of rock and roll (Elton John, Sting, and Madonna are among his most visible clients) and the virtues of pagan excess, he has a surprisingly soft spot for children. One hyperbolic visitor to various Versace households swore to me that Versace and d'Amico tended the children and that only Donatella -- whose love of nightlife causes d'Amico to dub her, affectionately, "the queen of the gays" -- liked life in the limo. (If that's true, she gets a lot of work done there: Donatella helps design both the Versus and the Istante lines.)

When I bring up the subject of his perceived limo-laden lifestyle, Versace laughs and says, "The truth is that I spend most of my time at home sleeping, watching TV, and working," and then he returns the converstaion to Men Without Ties: "The book is about men and about their beauty, but it is also a reminder about my career. The roots of my fashion are very classic. People judge me avant-garde, people judge me rock and roll, and I am smiling. I am the most classically influenced of the Italian designers, which no one seemed to realize until the last year."

Anyone flipping through Men Without Ties or staring at ads from almost any of Versace's recent campaigns would have to be doltish not to detect these classical ideas in play. In fact, the fun of looking at Versace's recent projects has been the feeling of freedom that the looking now imparts: You can at the same time muse about Roman marbles or about the poetry of Ovid and appreciate some model's hot ass or thighs.

I mention this to Versace. "Conventionally," he replies, "if you are a man who comments on a male beauty -- say, a movie star like Kevin Costner -- people immediately think you're gay. But that attitude is changing. For the younger generation things are already very different. People are feeling freer to comment on all kinds of beauty without feeling that it types them one way or another. It's great to feel that those of us who have fought for the right to enjoy all kinds of beauty will perhaps have made a difference. I say that even as I believe that recognizing beauty wherever and whenever it occurs is not just about the desire for sex."

Versace's category-transcending attitude strikes me as eminently refreshing and admirable. Unfortunately, not everyone is as evolved as he is. His American publisher, Abbeville Press, asked him to remove two photographs from the Italian edition of Men Without Ties before it would publish the book here. Both were full-frontal male nudes.

"The publisher is afraid, certainly," Versace admits before informing me slyly that the Italian edition is available for purchase at most Versace stores in the United States. He insists, however, that the American edition, which includes ten pages not in the Italian version, perserves his vision of men's fashion.

And just what is that vision these days? "It's about comfort," Versace replies, "about wearing what you like. It's also about feeling elegant in a formal situation without having to wear a tie." This does not mean, however, that anything goes. Versace insists on quality, on correct proportions, right down to the briefs. In fact, he deplores the new way of showing skivvies that has started showing up in fashion magazines here in and abroad. "The last Italian men's Vogue is full of ugly boys, boys on heroin, in underwear. I guess they needed a new trend."

Don't expect any ugly boys to show up in a Versace campaign any time soon. (This is, after all, the man who helped make South Beach and skin synonymous.) Before I left his hotel that day, Versace let me leaf through an unoffical photo album of a Boston-area shoot Bruce Weber had just completed for his fall men's campaign: 40 fresh-faced young men -- and Claudia Schiffer. A couple of the shots -- of seminaked boys enmeshed in a muddy rugby scrum -- seem destined for bedside status. And one photo of a long-haired young hunk is so blindingly beautiful that I can already count how many phone-booth posters of him will be ripped off before Christmas.

"You've created a new star," I say to Versace.

"We try," he replies.