CONTACTAbout UsCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Equal Entertainment LLC.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

We need your help

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Kurt Kauper was born in Indianapolis in 1966 and was raised in suburban Massachusetts. He received a BFA from Boston University in 1988 and an MFA in painting from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1995. He has had solo shows at ACME Gallery in Los Angeles and Deitch Projects in New York City. He has been included in numerous group exhibitions in both the United States and Europe, including the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Pompidou Center in Paris, the Kunsthalle Vienna, and the Stedelijk Museum in Ghent, Belgium. He has received numerous awards, including grants from the Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation, Tiffany Foundation, and Pollock-Krasner Foundation. His work is included in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Oakland Museum of Art, the Weatherspoon Museum, and the Yale University Art Gallery. He has taught at the Museum School in Boston, Yale, and Princeton University. He is currently a professor of art at Queens College, CUNY.

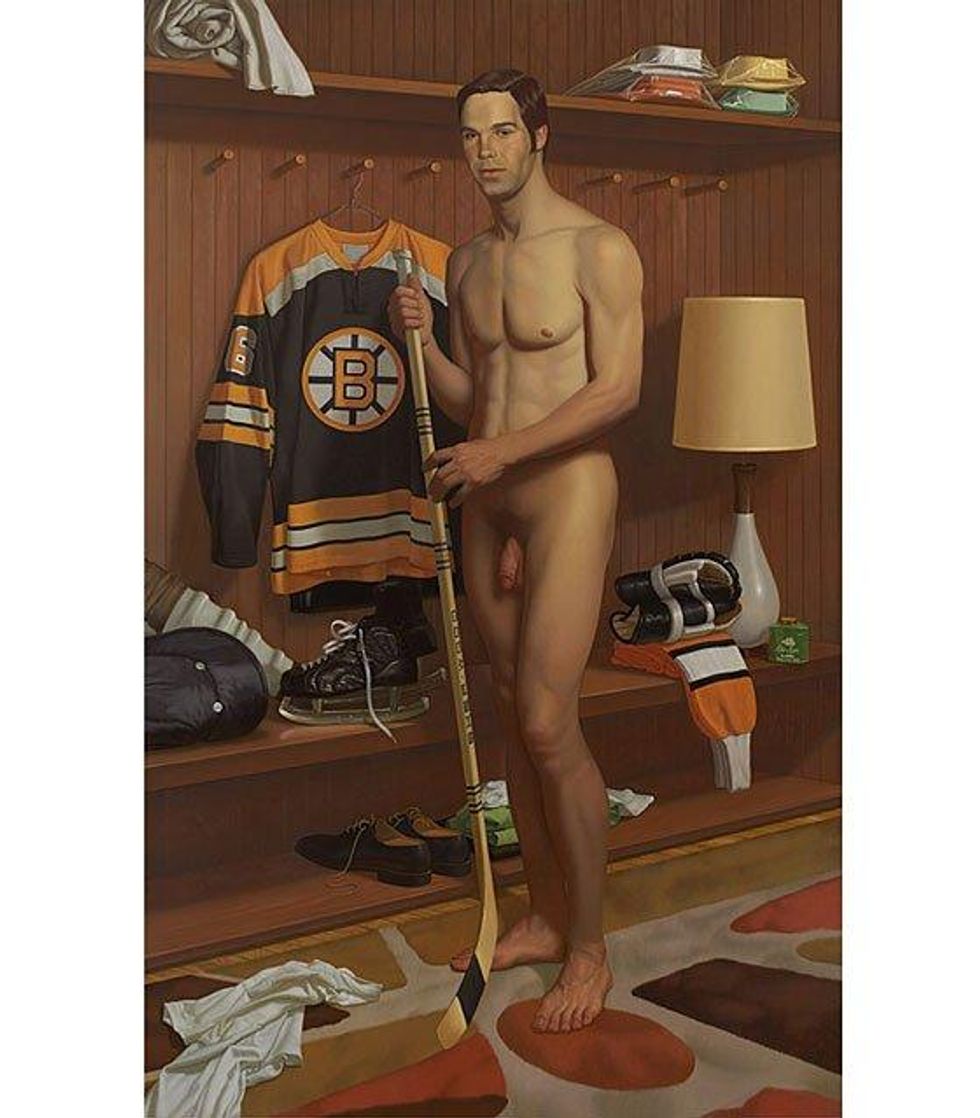

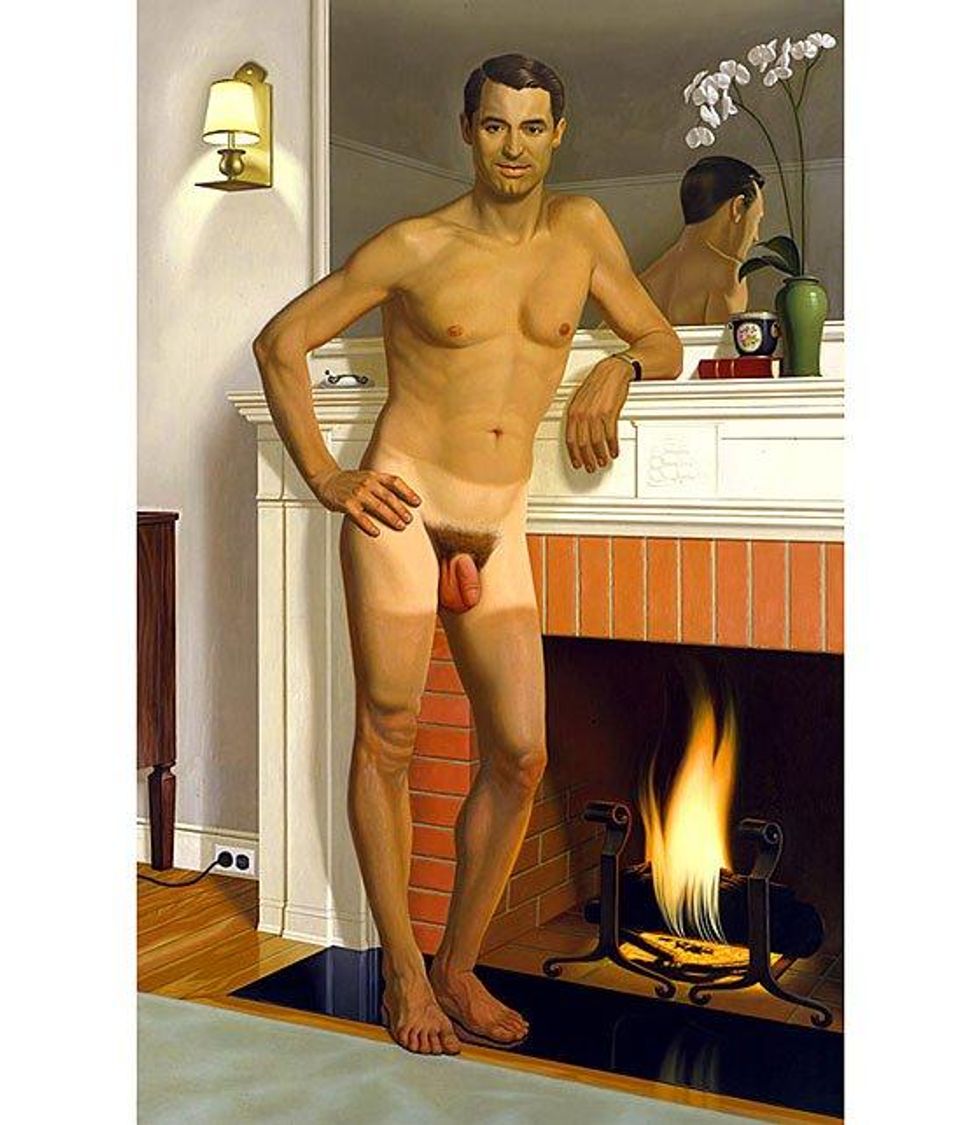

His paintings for the past 15 years have been images of familiar cultural icons -- opera divas, Cary Grant, hockey players, and Barack and Michelle Obama -- seen in a variety of unfamiliar ways. He will have a solo exhibition at ACME Gallery, Los Angeles, in 2012.

The Advocate:Why are you an artist?

Kurt Kauper: I'm an artist first because I was always told I was good at drawing, which meant, when I was a child, that I could draw more "realistically" than most. So from a very early age I felt validated for that, if nothing else. And I can't really recall being validated for much else. That validation gave me a sense of identity and a level of confidence that I could return to no matter what other difficulties I was confronted with.

Second, I grew up in a small, working-class, Irish Catholic town on the coast of Massachusetts; in that environment, athletic ability was privileged over all others. So I wanted to be a good athlete. I wasn't. And that made me something of an outcast, at least insofar as masculinity was defined. By the time high school rolled around, it was clear I had no future as an athlete, and academics bored me to tears. But I knew I could draw and paint really well, so my inability to do other things had no negative impact on me at all. In late high school I completely committed myself to art and started looking at painters like Ingres and David. And that changed my life.

Finally, my mother was an excellent artist and an art teacher. So my desire to be an artist was never discouraged. When I decided I wanted to be a painter, the decision was met with total support.

What catches your eye?

Just off the top of my head:

The light in New York City, especially in the late afternoon/early evening when the rays of the sun are running parallel to the cross streets.

Beauty that estranges: paintings by Ingres, Meredith Frampton, Alice Neel, Andy Warhol, John Currin; Ed Ruscha's artist books; Yasujiro Ozu's films; L'Atalante; faces like Chloe Sevigny's, Maria Callas's, or Lea Michele's.

Things that are just outside of our ability to comfortably categorize them.

Many other things -- those just come to mind.

Tell us about your process or techniques.

Tell us about your process or techniques.My process is to do a very careful line drawing of the composition I want. I then transfer that to the panel that's been covered with an earth-red imprimatura, which is simply a thin wash of color over the white ground. Recently, the earth red I've been using is burnt sienna. I then build up the lights and halftones of the paintings with lead white and ivory black, leaving the shadows as the earth-red imprimatura. So my underpainting is cool in the lights and warm in the shadows. I then build up the color in thin, though not entirely transparent layers, allowing a good deal of the underpainting to come through.

My recent subjects have been imaginary opera divas, Cary Grant without his clothes, hockey players without their clothes, Michelle and Barack Obama. So even though I would love it if they posed, there was little chance of that happening with any of these people. So my paintings are constructed from a combination of photographic sources and my own body reflected in a mirror. And I paint almost all the still life and landscape information in the paintings from life.

Tell us about the Diva Fictions -- why the word fiction in the title?

I started the Diva Fictions just after graduate school and just after completing a series of nude self-portraits. I had no idea what I wanted to paint. I just knew what I didn't want to paint: no more men, no more small paintings, no more fussing over tiny details like the highlights on teeth. And because the self-portraits had been interpreted as containing an autobiographical narrative, which they didn't, I knew I wanted to make paintings that couldn't possibly be interpreted as having anything to do with me. So just to keep working I arbitrarily chose to paint a large portrait of a woman in a ball gown. That's how I started the painting that would become Diva Fiction #1. I cobbled together a figure based on a range of photo sources I had and reflections of myself in the mirror and dressed her in a pink garment I found in a bridal magazine.

Meanwhile, I had bought a videotape called Maria Callas at Covent Garden. It includes the great act II from Tosca and two recitals. There are long stretches in the recitals where Maria Callas is receiving applause. You see her from the shoulders up, smiling and acknowledging the crowd. I was watching it one night and I was struck by her image, a smiling head-and-shoulder bust, framed by the television set. It seemed to me like an interesting contemporary portrait. So I started a drawing of Maria Callas on TV.

As I was working on both images side by side in the studio -- the woman in the ball gown and Maria Callas -- they started to suggest a narrative in relationship to one another. The Maria Callas image seemed to me to be perfectly emblematic of my relationship to tradition. I've always loved Western painting and have always felt nourished by it. But at the same time, it has always seemed to me something of a straitjacket that limits my possibilities as an artist. Maria Callas is an artist I love and am constantly inspired by, but I can never actually see her or hear her. She exists only through the distance of recordings. No matter how much I love her art, there will always be an unbridgeable gap that separates me from a full experience of her and an understanding of her within the context of her time. That's exactly how I feel about my relationship to traditional art.

Right next to the Maria Callas in my studio, I was painting the woman in a ball gown, a reconstructed figure made from fragments of images, fragments of my body, fragments of my imagination. If the Maria Callas drawing represented my relationship to tradition, I started to think of the woman in a ball gown as my invention of a contemporary identity out of tradition; and because that process of reconstruction out of limiting traditions is exactly what opera divas do, both in their artistic and social identities, I started to think of that painting as a portrait of an invented diva. So she became Diva Fiction #1. That idea, of creating a contemporary identity out of artistic and social traditions, is something that has remained part of my work to this day. I wanted the word fiction in the title because I wanted it to be clear that these weren't paintings of historical divas, that they were about fabricating an identity.

Why hockey players? A hockey fan ... or ... ?

I'm not a hockey fan. Many people have asked me recently if I'm happy that the Boston Bruins just won the Stanley Cup, and I couldn't care less. But when I was 6, I -- like many other boys in Boston -- idolized Bobby Orr. Looking back, it was as if I was in love with him. And that's part of the reason I made those paintings, although I wasn't consciously thinking that at the time. I just know I was casting about for something to paint after finishing the diva paintings. It occurred to me, for no reason I can remember, to start paintings based on hockey cards from 1972: The first hockey paintings were the oval portraits. The shape of each portrait comes from the cards' graphics, each of which shows a head-and-shoulder photo of the player inside an oval frame. After blocking in the first painting, one of Bobby Orr, I started the Cary Grant paintings, so the hockey card painting sat around my studio in an unfinished state for several years. Looking at it over time, I realized that what I liked about it was the tension between the original intent of the cards and the way they could be received by the viewer. In other words, sports cards are meant to embody an ideal of masculinity and transmit that ideal to young boys. And yet the designers of the cards represented each player in head and shoulders, framed in a small oval. The cards were more like locket portraits than anything else. I thought about the tradition of locket portraits, small, intimate images of loved ones, meant to be worn next to the heart. I think of it as a "feminine" tradition. The cards' graphics threaten the ideal of masculinity they were meant to embody. I love that slippage in portraits, when the intent and the reception of the painting are at complete odds.

Those are interests that carried into the Cary Grant portraits: I wanted to make paintings that, instead of confirming traditional, stable representations of desire, confounded the perceived relationship between the maker of the image and the object of desire represented. I'm interested in how representations of sexuality are perceived and understood by viewers. I wanted viewers to wonder whose desire was being represented and to be uncertain as to the identity of the artist. Cary Grant seemed the perfect subject through which to engage in that investigation.

When I started those paintings, there was a highly publicized return to figurative painting. Artists like John Currin, Elizabeth Peyton, and Lisa Yuskavage were the most prominent, but there were many others. And yet none of the artists most frequently discussed were painting the male nude. It was always the female nude, and in many ways very traditional representations of the female nude, both technically and conceptually. And by and large the reception of these paintings, by critics and collectors, was that they were reinscriptions of traditional desire; now, I want to point out that I think this is a misread, and I find the work of all the artists I mentioned to be much more complex. But that was nevertheless the discourse that surrounded the work. So I loved the idea of making paintings of nudes that resisted attempts to categorize the desire represented.

And finally, I loved the idea of making paintings that used nakedness as a gesture of both admiration and iconoclasm.

From Your Site Articles

xtyfr

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Bizarre Epstein files reference to Trump, Putin, and oral sex with ‘Bubba’ draws scrutiny in Congress

November 14 2025 4:08 PM

True

Jeffrey Epstein’s brother says the ‘Bubba’ mentioned in Trump oral sex email is not Bill Clinton

November 16 2025 9:15 AM

True

Watch Now: Pride Today

Latest Stories

Lesbian federal worker pleads for answers about wife trapped in immigration detention limbo

December 16 2025 5:08 PM

Michigan Republican U.S. Senate candidate Mike Rogers surrounds himself with hardcore LGBTQ+ rights opponents

December 16 2025 2:53 PM

True

Florida city installs Pride bike racks after being forced to remove rainbow crosswalks

December 16 2025 2:21 PM

Ariana Grande and Jonathan Bailey in talks to star in West End musical

December 16 2025 12:26 PM

Netflix's 'Boots' is canceled: Stars react to the heartbreaking news

December 16 2025 11:37 AM

How this Minnesota city redefined LGBTQ+ rights 50 years ago

December 16 2025 11:25 AM

Gen Z women are more likely to identify as bisexual but still embrace lesbian label: study

December 16 2025 11:10 AM

Is Texas using driver's license data to track transgender residents?

December 15 2025 6:46 PM

Rachel Maddow on standing up to government lies and her Walter Cronkite Award

December 15 2025 3:53 PM

Beloved gay 'General Hospital' star Anthony Geary dies at age 78

December 15 2025 2:07 PM

Rob Reiner deserves a place in queer TV history for Mike 'Meathead' Stivic in 'All in the Family'

December 15 2025 1:30 PM

Culver City elects first out gay mayor — and Elphaba helped celebrate

December 15 2025 1:08 PM

Trending stories

Recommended Stories for You

Christopher Harrity

Christopher Harrity is the Manager of Online Production for Here Media, parent company to The Advocate and Out. He enjoys assembling online features on artists and photographers, and you can often find him poring over the mouldering archives of the magazines.

Christopher Harrity is the Manager of Online Production for Here Media, parent company to The Advocate and Out. He enjoys assembling online features on artists and photographers, and you can often find him poring over the mouldering archives of the magazines.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes