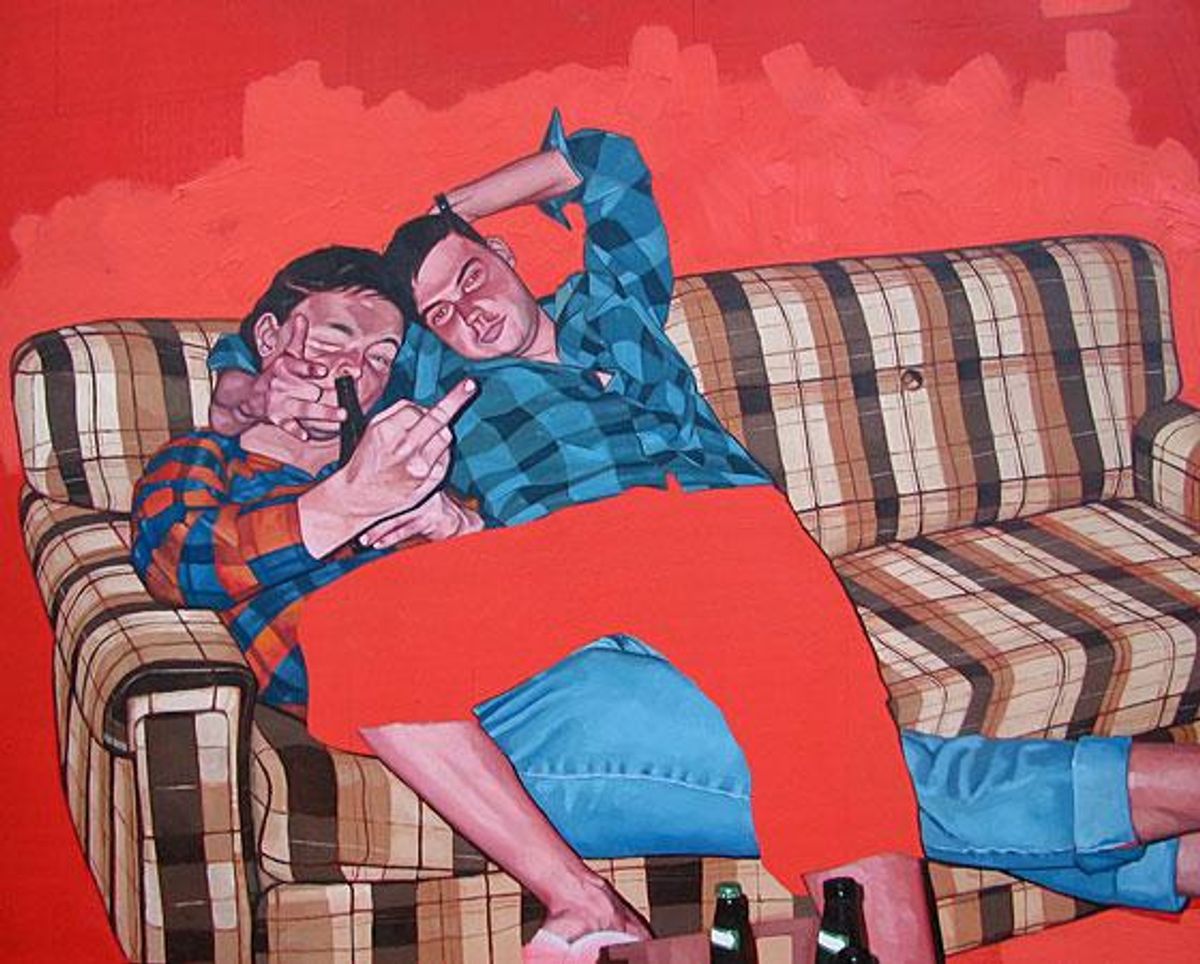

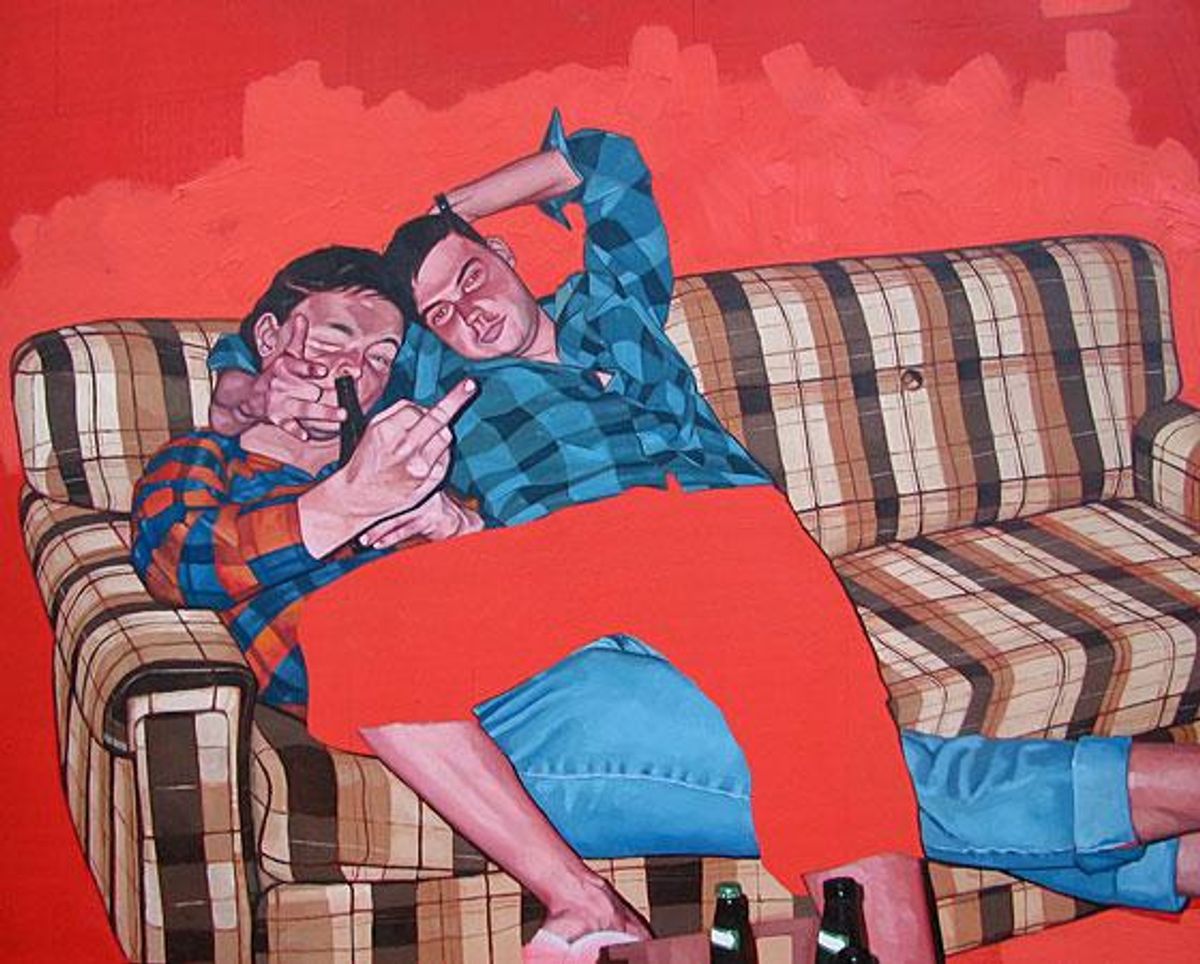

Scott Waters's work says something about men, masculinity, and the delicate balance of a macho identity.

August 27 2011 4:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

xtyfr

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Scott Waters's work says something about men, masculinity, and the delicate balance of a macho identity.

As LGBT people, we are exceptions to the rule. Artist Scott Waters certainly fits into that category. We happened across his artwork on the Web and felt that it said something important about men, masculinity, and the delicate balance of a macho identity. And it also said something about war, military service, and what happens to men who become soldiers. Waters is straight, but he agrees with us that there is something important here for a gay viewer. He says, "My work certainly has a strong queer underpinning, and many of the issues come from an examination of the homosocial, but I'm straight."

So it would seem that Scott Waters is also an exception to the rule. Thus, sometimes it is less important that the artist we feature be LGBT than that the work be interesting and illuminating viewing for an LGBT audience.

The Advocate: Why are you an artist?

Scott Waters: To some degree I became an artist through the process of elimination, trying to build a career in more financially viable and stable job options (soldier, teacher, graphic designer). As each one lost its charm, I came to understand that the notion of artist could indeed be financially manageable (if not lucrative).

But as to what art offers me, it is best seen prosaically: using a skill set that I have an aptitude for to address issues that compel me.

At least for me, the visual art object is evidence of an idea -- it is the thing which stands for the idea while also being its own idea.

What catches your eye?

So far as art making goes, I am almost always looking for images that support or engage an idea. It's not so common that the visual is the conceptual instigator. But when I'm looking for an image that supports an idea, it is often contradiction or ambiguity that attracts me. Ambiguity can arise via the image's narrative as well as its formal elements.

Also, though, as I mostly work on projects (rather than individual pieces), it might be a fairly straightforward image that, when seen in the context of a larger body, takes on an air of the uncanny. In this way, the images I choose need to be considered from various distances.

Tell us about your process or techniques.

I'm a big fan of the grid as a way to help with the initial drawing. Keeping a grid in the finished painting is a way to play with the notion of magic, illusion, talent (or lack thereof) in painting. The grid shows a structure and removes some of the mystery. It says clearly, "These are my limits." I don't draw freehand on the large paintings. but neither do I ever use a projector. Maybe I am trying to strike a balance somewhere between practicality and mystery. Given the military subject matter, this tension seems very relevant.

The dialectic between paint's material qualities and how artists manipulate it is important for any number of reasons. One of these is the 20th-century painting dance between the subject and the object, between honesty and illusion, especially in relation to the previously held belief in photography's authenticity in relation to painting.

And again, because of the military and documentary elements, these tensions are especially germane.

How do you choose your subjects?

Overall, my images are chosen based on what I am interested in engaging so far as authenticity, memory, and illusion are concerned.

In the Hero Book project all the images were culled from my own collection of photos from my infantry days. The explicitly autobiographical and memoir-based content tended to require my own sources. But I was also interested in the malleability of memory as well as the tension between photographic source and painted response.

The choices made for each image are partially based on the conceptual base for the project, so in the fight paintings, I staged intentionally awkward scenes by recruiting friends (paying them with beer), playing up their specific responses to the task of pretending to fight: melodramatic, awkward, enthusiastic, or totally devoid of emotion. It was their responses, rather than the idea of "fighting," that was more engaging.

How do you describe your work?

Painterly realism that addresses the aesthetics and draw to violence in Western society.

What artists do you take inspiration from and why?

Leon Golub and Tim O'Brien are two artists -- painter and writer respectively -- who continue to give me the will to carry on.

There are any number of artists who I look to, respect, and whose work I'm excited by, but Golub and O'Brien stand out for their dogged pursuit of a practice which has/had a singular focus over decades.

One of my anxieties as an artist is of pursuing one main trajectory: that of understanding cultures of violence and fraternal socialization, especially through the military model. Sometimes I worry that I'm working in an art ghetto, but when I read any of O'Brien's brilliant books on Vietnam and its fallout -- an area he focused almost on exclusively for decades -- I recognize that working in a niche is not a hindrance if it offers something specific, eloquent, and magical to the world.

Visual art school was my start point, though, and Leon Golub was the first visual artist I came across who looked long and hard at cultures of violence, oppression, and trauma. He was the first case that let me see what I was interested in, what compelled me, might actually be viable for an artistic career.

I am only me, and me has something very specific to say. These things are said for the benefit of the world but also from a necessary drive to understand something inside myself. This drive is, I believe, something many can relate to.

You identify as straight, but your viewpoint of masculinity seems to be informed by someone who is both inside and outside the orientation. Who are these guys?

If we can use the term "lucky," I'm lucky enough to have had experiences -- careers -- which sit on the supposed opposite spectrums of male sexuality. Having been an infantry soldier and now a visual artist and writer, my life has had some stark polarities.

Most of the guys in these paintings are soldiers (or were at the time), and I have to admit that about half of them most likely don't know about these paintings. Of course, the limits of what we might call a broken social contract are a compelling element in the project. The making-public-through-painting of these private photographic moments is what gives the work its greatest impact. Or so I believe.

From your unique viewpoint, what do you think of lifting the ban on gay men serving openly in the military?

There seems to be a bit of danger in using "the military" as a blanket term, simply because different areas and elements are quite disparate. Openly gay men in the combat arms are likely to have a harder time than pay clerks on an Air Force base. Just as gay marriage is accepted with joy in some areas of civil society (and open hostility and paranoia in others), so too will the range of reactions vary in as wide a culture as "the military."

While homophobia is as much a part of military culture as is homosociality, I do believe that the military should be an extension of society, while also requiring its necessary separation. If soldiers are also citizens, then human rights that exist for civvies should also exist for soldiers. Certainly there will be outrages and harm along the way, but resetting norms always comes with tumult.

Guns, beer bottles being shoved in mouths, and violent clinches. Is your art also addressing repressed man-to-man sexual expression?

I would like to think my paintings exist equally in repressed and celebrated homosociality. There's the standard line within hypermasculine cultures that says "the gayer you act, the straighter you are." This, however, is simply a holding architecture for the many variables and personalities that exist within these cultures. For some, repression is part of the acting out, but for others there exists a line that cannot be crossed. Like any insular, separated culture, understanding the social cues -- the parlance and innuendo -- is what marks you as an insider.

One common thread is the attempt to display affection by males who often are unused to such closeness. So for (personal) example, holding your friend's penis because he's too drunk pull it out and pee himself shows a dedication and closeness to fraternity that concurrently sits right on the edge of sexual without crossing over.

Because the military draws principally from young males, their personality is very malleable and vulnerable. At first displaying affection is difficult, but once they learn to say "I love you, man" the world opens up into something where you can make your own rules for your own tribe. Sometimes repression is the inevitable result of trying to understand such deep love within a hyperviolent culture.

It is a strange tribe, one worthy of any ethnographer.

Born in Preston, England, Waters immigrated to Canada with his family. After serving as an infantry soldier in the Canadian Forces he began an academic career, which eventually led to a career as a visual artist and writer. Waters received a bachelor of fine arts degree from the University of Victoria and a master of fine arts degree from York University, and he has lived in Toronto for the past 11 years.

Represented by LE Gallery in Toronto, has had Waters solo exhibitions at venues including Rodman Hall, the Art Gallery of Southwestern Manitoba, and the Alternator Gallery. Notable touring group exhibitions include "A Brush With War: Military Art from Korea to Afghanistan" and "Diabolique."

Twice selected to participate in the Canadian Forces Artist Program, Waters has also undertaken residencies at Open Studio in Toronto and the Klondike Institute for Art and Culture in Dawson, Yukon.

Publications include the illustrated memoir, The Hero Book (Conundrum Press); features in Border Crossings, Public, Legion Magazine, and 100 Artists of the Male Figure; and writings in Drain Magazine, Kiss Machine, Contemporary Verse 2, and the upcoming anthology Embedded on the Homefront.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered