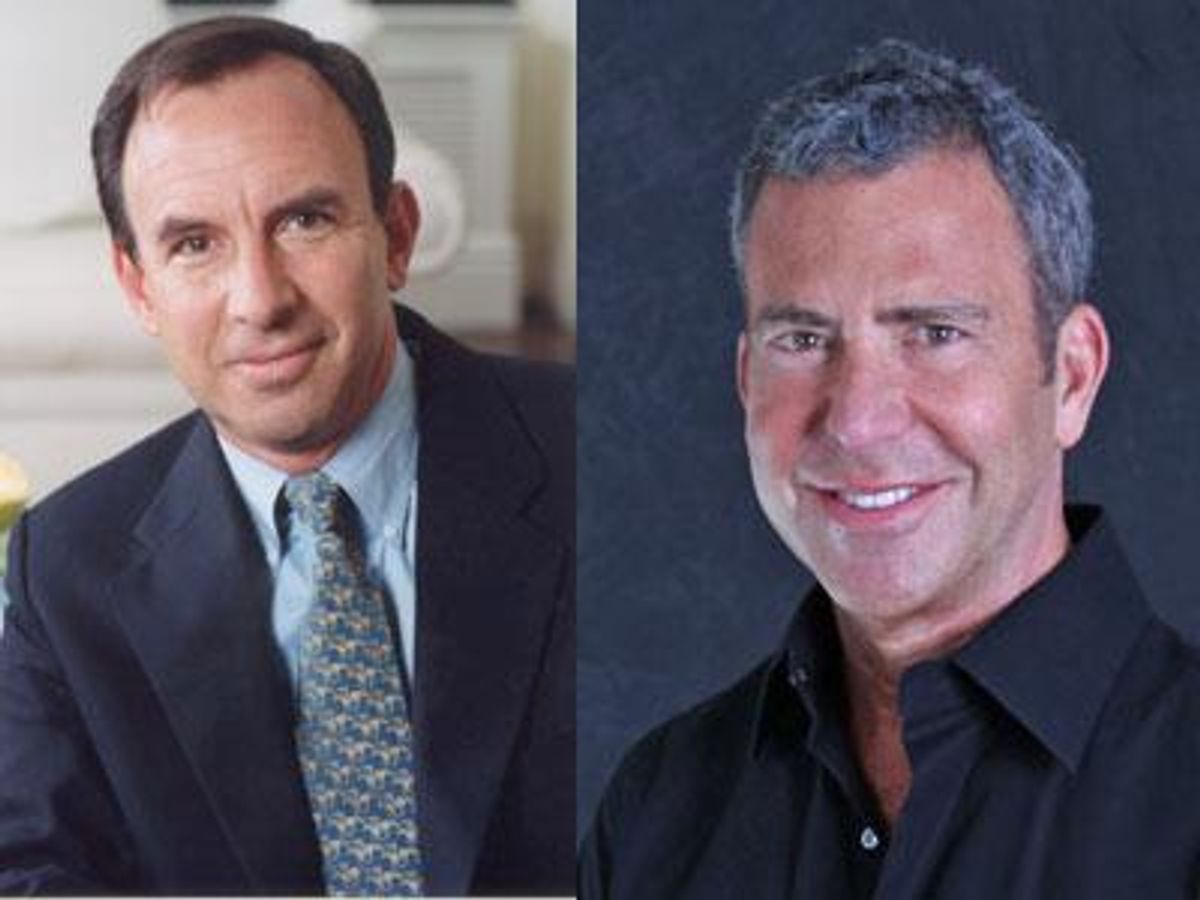

Jeffrey Sharlach is the author of the new novel Running in Bed (Two Harbors Press), which tells the story of Josh Silver, an ambitious gay New York advertising executive, as he comes out of the closet and sets off in search of true love, finding himself in the process. Set in New York's Greenwich Village and Fire Island in the late 1970s, it covers a path similar to that trod by Andrew Tobias a decade before at Harvard, which he related in The Best Little Boy in the World, first published in 1973. We asked them to both look back at their coming-out experience and tell us how they view the experience now, decades later.

Jeffrey Sharlach: That's probably the most autobiographical part of Running in Bed. Josh's coming-out is a lot like Jeffrey's coming-out. For me it was 1977, I was 24, and it was literally right after I finished law school and was supporting myself for the first time rather depending on my parents. I went to a therapist, told him I wanted to be straight. And fortunately, rather than send me for electroshock therapy, which was still in use then, he asked a simple question: "Why?" From that point it was less than two months before I got up the courage to go to my first gay bar. And after that things moved even faster.

Andrew Tobias: Was that therapist gay? Did he guide you through the process?

Sharlach: I wasn't looking for a gay therapist. My goal was to be converted to heterosexuality. And in fact he was straight, something he told me that first night. But honestly, I consider myself very lucky, since at the time I could have just as easily ended up in conversion therapy of some sort. After that fateful first session when the therapist asked me "Why?" I set out to read everything I could on the subject and, as I've told you before, I started with your book, which really helped push me out of the closet although you were writing under a pseudonym at the time.

Tobias: Was I ever. It was such a different time. Not a single openly gay politician in any state or city in the entire country [Elaine Noble would not be elected to the Massachusetts House until 1974], let alone Congress, just to give you a data point. And, really, that was the least of it. It was shameful to be gay -- the worst thing you could be -- and so I opened the book with this disclaimer, 40 years ago: "This is a book about owning up to one's true identity, yet I have ... signed it with a pen name ... the least I can do for my parents, who have done a great deal for me. Ideally, of course, it would not be necessary. But, then again, ideally there would be no reason to write a book like this at all."

Sharlach: How do you think our experiences were different from those of LGBT people today?

Tobias: For many kids coming out today, it's still awfully tough, obviously. Sometimes tragically so. But when 24% of prime-time network TV shows have gay characters? And the president of the United States has said Modern Family is his family's favorite show? And Glee is a smash? And Ellen is beloved? And even Brigham Young University has a gay-straight alliance? And most younger people favor marriage equality? And so many American cities have joyous and for the most part noncontroversial pride parades? And have I even mentioned the Internet? I like to think the level of fear and isolation and depression and hopelessness, if you could measure it objectively -- while still overwhelming in all too many cases -- is just a small fraction of what it was. Is that your view?

Sharlach: I think a lot depends on where they happen to live and their own family environment. Probably many of them struggle with it even more than I did, even today. But I think the big thing is the visibility now of gay people. When I was a teenager, the only thing you ever heard about homosexuals was when they were arrested for molesting children, fired from their jobs, or otherwise disgraced. We never had any role models of successful gay men or women. That's why when I read your book in 1977 it was such a revelation for me: Here was a nice Jewish boy who came out and he was actually happy about it.

Tobias: Happy? I was ecstatic. In fact, while I wouldn't wish on anyone my 12 years in the closet -- from age 10 or 11, when I knew I had this horrible defect, to age 23, when I discovered that millions of wonderful people were just like me and that there was a whole amazing, wonderful world out there and that there was nothing wrong with me -- it sure did make me appreciate my "freedom," once I found it, all the more.

Sharlach: I also think a big difference today is that young gay people are much less isolated than we were, and it's a lot easier for friendships to continue when they're not interrupted by the drama of coming out, since many of them are never "in." I was ostensibly straight through high school, college, and law school, so with all of my friends then, I talked about women, went on dates, and did my best to be perceived as heterosexual, although I'm not sure how many of them I actually convinced. When I came out at 24, and maybe this was because it was such an abrupt shift for me, happening over a period of weeks, I lost touch with most of those friends and, for the first years anyway, spent nearly all of my time with fast-expanding group of gay friends, going to gay bars, and sharing our experiences together.

Tobias: So your straight friends cut you off once they found out you were gay?

Sharlach: No, actually it was the other way around. I was just so excited to be myself for the first time and acting on all those suppressed feelings that I just wanted to be immersed in it any free hours when I wasn't working. Also, I was embarrassed and ashamed: not for being gay, but for having lied all those years and pretended to be someone I wasn't. So it was easier to just cut those people out than try to explain.

Tobias: I basically loved telling my straight friends. Mostly for all the wrong ego reasons, perhaps -- it sure focuses the attention on you, that's for sure -- but still. And many of them remain close, though there's no question that, the minute I came out, I began to spend much less time with them. The only people I didn't love telling and kept hesitating to tell and finally told only long, long after I had told everyone else -- and waited much too long to tell -- were, naturally, my parents. You?

Sharlach: My parents struggled with it, but again, you have to remember, what they knew about homosexuals was what they were taught in school and saw in the media: We were criminals, doomed to miserable lives. They came around very quickly, and it wasn't long before they became active in Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays and started to march in the annual New York Gay Pride Parade.

Tobias: My parents' reaction was not exactly as described at the end of my book -- as I explain in the first chapter of the sequel that came out 25 years later. But, yes, my dad took me aside the day he met Scot to say, "He's a very nice young man" -- I get pretty choked up just thinking about how much that meant to me (and also missing Scot, who died in 1990, and my dad, who died in 1983) -- and my mom quickly came to adore Charles, but could never quite figure out how to introduce him. "And this is Andy's very, very special friend Charles," she would say, or something like that. So it sounds as though both of us pretty much lucked out, parentally.

Sharlach: I do think there was a sense of "being different" when I came out in the '70s that wasn't all bad -- it was unifying in a way, and I hope I'm not romanticizing the past too much by saying I think we were more supportive of one another. Especially in business, when you found someone else who was "family" they would often take you under their wing. I think these days it's just not that a big a deal and I guess that's the way it should be.

Tobias: Oh, I think there's still a lot of under-wing-taking. Just watch how many aspiring young writers are going to find their way to your Facebook page after reading your wonderful book. I'll bet you go out of your way to help every single one.

**

Andrew Tobias has been the treasurer of the Democratic National Committee since 1999. He has received the Gerald Loeb Award for Distinguished Business and Financial Journalism, Harvard Magazine's Smith-Weld Prize, GLSEN's first Valedictorian Award, and the Consumer Federation of America Media Service Award. His writings have appeared in publications including Esquire, New York, Parade, Time, The New York Times Magazine, and Harvard Magazine. He is the author of 12 books, and his novel The Best Little Boy in the World has been in print continuously since 1973.

Jeffrey Sharlach is the author of Running in Bed, hitting booksellers later this month. He is the founder of JeffreyGroup, a top public relations and marketing agency that focuses largely on Latin American markets and Hispanic-American consumers. In 2007 he was appointed adjunct associate professor in the Department of Management Communication at the New York University Stern School of Business, where he currently teaches.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered