Chapter 2

A Decade of Loss

Ryan was not the first friend I lost to AIDS, and he was not the last. So many have been taken from me by this disease--sixty, seventy, eighty, I honestly don't know how many. I'd rather not count. But I never want to forget them.

That's why I have a chapel in my home in Windsor, in an old orangery on the property. It's where I go to remember the people in my life who touched me, who made me the person I am today. When I go inside it's like stepping back in time. I'm flooded with sadness and warmth.

Pictures adorn the walls. My grandmother. Princess Diana. Gianni Versace. Guy Babylon, the amazing keyboard player I lost to a heart attack in 2009. Then there's another wall, full of plaques that list name after name after name. People who, in my memory, are frozen in time as young, vibrant, and full of life. None of them are here anymore. They all died of AIDS.

These were close friends, lovers, and people who worked for me. Many of them died in the 1980s, wiped out by a cruel and relentless plague. The first person I knew who died of AIDS was my manager's assistant, Neil Carter. He was a lovely young man, and I was distraught when I learned he had the disease. Three weeks later, he was dead. His was the first plaque I placed in my chapel.

Today, AIDS in the West is increasingly thought of as just another chronic condition that can be controlled with medication. We see people like Magic Johnson living long and healthy lives, and we wouldn't know they had such a terrible disease unless they told us. Thank heaven for that.

But when you got AIDS in the '80s, you died--quickly and horribly.

The physical depredations of AIDS were bad enough. Then there was the terrible indignity that AIDS visited on the infected: the shame and the stigma.

Very early on, there were far too many in the media, religious institutions, governments, and the general public who sent an unmistakable message to people with AIDS: We do not care about you.

They were made to feel that they had somehow brought the disease upon themselves through their own sinfulness or lack of virtue.

For a while, to the extent the epidemic was considered at all, it was considered an affliction of "them" -- the queers, the junkies, the immigrants, those people we don't like to think about or talk about. But AIDS became a disease of "us" the moment rumors hit that it was in the general blood supply. First, AIDS began showing up in people with hemophilia, like Ryan. The real panic took off when patients started contracting the disease from blood transfusions during surgery, and although the numbers would ultimately turn out to be relatively small, the public began to feel as if anyone could get the disease. "Fear of AIDS Infects the Nation," blared a U.S. News & World Report headline at the time.

By early 1983, scientists had not identified precisely what virus was causing AIDS, but they knew for certain that casual contact did not transmit it. Some public health organizations, including the CDC, did what they could to get the facts out, but they were overwhelmed by a tide of misinformation, often from people and organizations that should have known better. On May 6, 1983, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a news release with the headline "Evidence Suggests Household Contact May Transmit AIDS."As late as 1985, a White House lawyer who is now the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, John Roberts, sent a memo to President Reagan saying, "There is much to commend the view that we should assume AIDS can be transmitted through casual or routine contact."

With these mixed signals coming from high-ranking government officials and the medical establishment, it's no wonder that people indulged in irrational fears. In New York, the state Funeral Directors Association recommended that its members refuse to embalm people who had died of AIDS. In Louisiana, the state house of representatives overwhelmingly passed a measure permitting the arrest and quarantine of any person with AIDS (the law was thankfully revoked soon thereafter). In San Francisco, when a local TV station tried to tape a special to increase public understanding of AIDS, the studio technicians refused to let people living with HIV/AIDS onto the set.

Across the country, reports began to emerge of targeted persecution and violence against people with HIV/AIDS, particularly gays. In Seattle, one group of young men rampaged through a local gay district, beating people with baseball bats and raping two men with a crowbar. When one of the attackers was arrested, he told police, "If we don't kill these fags, they'll kill us with their fucking AIDS disease."

The AIDS epidemic flared and raged in the '90s because no one put it out when it was smoldering in the '80s.

In 1987, President Reagan finally gave a speech on AIDS. It was, in many ways, an underwhelming speech, filled with platitudes and too few commitments to action. But finally the president said what the nation needed to hear: "It's also important that America not reject those who have the disease, but care for them with dignity and kindness... This is a battle against disease, not against our fellow Americans." We could have used those words in 1982, but they were better late than never.

As the Reagan administration was waking up from its long AIDS slumber, the scientific fight against the disease was moving forward as well. In March 1987, the first treatment to slow the progression of AIDS was approved by the FDA. The drug, AZT, was an antiretroviral that had proven in clinical trials to delay the onset of AIDS in HIV-positive patients. Patients who received AZT treatment remained HIV-positive--the drug wasn't a cure--but it allowed them to live a bit longer with the virus. The drug was adding a few months or years to patients' lives. And it often had awful side effects. In fact, the symptoms caused by AZT were sometimes worse than those of the disease itself. The anemia was crippling; it caused hemophiliac-like symptoms. Some people were taken off the drug because it was too toxic, but often, doing so would cause a spike in AIDS symptoms. It was a horrible way to survive. I remember some of my friends taking AZT and suffering terrible nausea and vomiting. A few developed anemia. But after years of utter despair, this drug was a ray of hope. It was something to slow the disease down, and it promised more treatments to come.

For many, however, AZT would come too late to make a difference. That was tragically the case for Ryan White, as it was for one of my very closest friends, a man whom I loved dearly, and a man who was loved by millions of people around the world: Freddie Mercury.

For many, however, AZT would come too late to make a difference. That was tragically the case for Ryan White, as it was for one of my very closest friends, a man whom I loved dearly, and a man who was loved by millions of people around the world: Freddie Mercury.

Freddie didn't announce publicly that he had AIDS until the day before he died in 1991. Although he was flamboyant onstage -- an electric front man on par with Bowie and Jagger -- he was an intensely private man offstage. But Freddie told me he had AIDS soon after he was diagnosed in 1987. I was devastated. I'd seen what the disease had done to so many of my other friends. I knew exactly what it was going to do to Freddie. As did he. He knew death, agonizing death, was coming. But Freddie was incredibly courageous. He kept up appearances, he kept performing with Queen, and he kept being the funny, outrageous, and profoundly generous person he had always been.

As Freddie deteriorated in the late 1980s and early '90s, it was almost too much to bear. It broke my heart to see this absolute light unto the world ravaged by AIDS. By the end, his body was covered with Kaposi's sarcoma lesions. He was almost blind. He was too weak to even stand.

By all rights, Freddie should have spent those final days concerned only with his own comfort. But that wasn't who he was. He truly lived for others. Freddie had passed on November 24, 1991, and weeks after the funeral, I was still grieving. On Christmas Day, I learned that Freddie had left me one final testament to his selflessness. I was moping about when a friend unexpectedly showed up at my door and handed me something wrapped in a pillowcase. I opened it up, and inside was a painting by one of my favorite artists, the British painter Henry Scott Tuke. And there was a note from Freddie. Years before, Freddie and I had developed pet names for each other, our drag-queen alter egos. I was Sharon, and he was Melina. Freddie's note read, "Dear Sharon, thought you'd like this. Love, Melina. Happy Christmas."

I was overcome, forty-four years old at the time, crying like a child. Here was this beautiful man, dying from AIDS, and in his final days, he had somehow managed to find me a lovely Christmas present. As sad as that moment was, it's often the one I think about when I remember Freddie, because it captures the character of the man. In death, he reminded me of what made him so special in life.

Freddie touched me in a way few people ever have, and his brave, private struggle with AIDS is something that inspires me to this day. But his illness, I'm ashamed to admit, wasn't enough to spur me to greater action. I've railed against government and religious leaders who were indifferent to or who actively undermined the fight against AIDS. They deserve every bit of criticism I'm throwing their way. They could have done so much more.

I could have done so much more, too.

Instead, I spent the '80s sinking ever deeper into a drug addiction that began in 1974, when I was recording my album Caribou in Colorado. Even though I'd been a full-fledged rock star for years by then, I still hardly even knew what cocaine was. I was unbelievably naive. I remember walking to the back of the studio one day, seeing a line of white powder on the table, and asking my manager, "What on earth is that?" He told me it was cocaine. I figured I'd take a little sniff.

Instead, I spent the '80s sinking ever deeper into a drug addiction that began in 1974, when I was recording my album Caribou in Colorado. Even though I'd been a full-fledged rock star for years by then, I still hardly even knew what cocaine was. I was unbelievably naive. I remember walking to the back of the studio one day, seeing a line of white powder on the table, and asking my manager, "What on earth is that?" He told me it was cocaine. I figured I'd take a little sniff.

I knew some people who could casually do cocaine once a month. I was not one of those people. By the 1980s, I was completely hooked on coke, booze, and eventually food. Then I became bulimic, too. I was guilty of every single one of the seven deadly sins, except sloth. No matter how bad it got, I never lost my work ethic or my love of music.

But I had become numb to everything else. I had friends dying left and right of AIDS. I would go to the funerals. I would cry. I would mourn, sometimes for weeks on end. None of this changed my behavior. In fact, it just got worse. I was doing more drugs to block out the horror of it all. I was sleeping around without protection, drastically increasing the chances I would contract the very same disease that was killing the people closest to me. It's no small miracle that I never contracted HIV myself.

I was extremely selfish and self-destructive. I could barely hold myself together, let alone be out there with the Elizabeth Taylors of the world as an AIDS advocate.

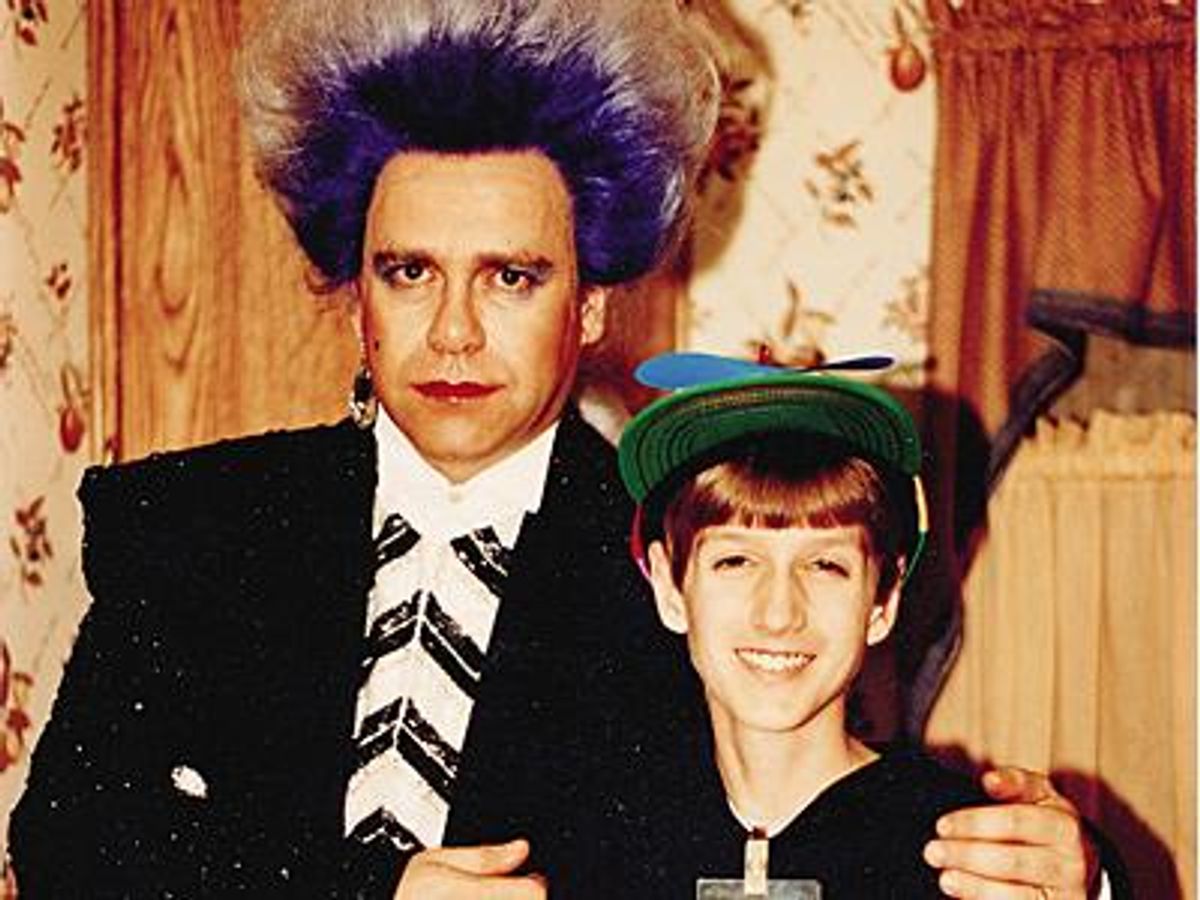

It took Ryan's death to wake me up, to transform my life.

To learn more about the Elton John AIDS Foundation go here. To purchase Love is the Cure, go here, here, or here.

With these mixed signals coming from high-ranking government officials and the medical establishment, it's no wonder that people indulged in irrational fears. In New York, the state Funeral Directors Association recommended that its members refuse to embalm people who had died of AIDS. In Louisiana, the state house of representatives overwhelmingly passed a measure permitting the arrest and quarantine of any person with AIDS (the law was thankfully revoked soon thereafter). In San Francisco, when a local TV station tried to tape a special to increase public understanding of AIDS, the studio technicians refused to let people living with HIV/AIDS onto the set.

With these mixed signals coming from high-ranking government officials and the medical establishment, it's no wonder that people indulged in irrational fears. In New York, the state Funeral Directors Association recommended that its members refuse to embalm people who had died of AIDS. In Louisiana, the state house of representatives overwhelmingly passed a measure permitting the arrest and quarantine of any person with AIDS (the law was thankfully revoked soon thereafter). In San Francisco, when a local TV station tried to tape a special to increase public understanding of AIDS, the studio technicians refused to let people living with HIV/AIDS onto the set. For many, however, AZT would come too late to make a difference. That was tragically the case for Ryan White, as it was for one of my very closest friends, a man whom I loved dearly, and a man who was loved by millions of people around the world: Freddie Mercury.

For many, however, AZT would come too late to make a difference. That was tragically the case for Ryan White, as it was for one of my very closest friends, a man whom I loved dearly, and a man who was loved by millions of people around the world: Freddie Mercury. Instead, I spent the '80s sinking ever deeper into a drug addiction that began in 1974, when I was recording my album Caribou in Colorado. Even though I'd been a full-fledged rock star for years by then, I still hardly even knew what cocaine was. I was unbelievably naive. I remember walking to the back of the studio one day, seeing a line of white powder on the table, and asking my manager, "What on earth is that?" He told me it was cocaine. I figured I'd take a little sniff.

Instead, I spent the '80s sinking ever deeper into a drug addiction that began in 1974, when I was recording my album Caribou in Colorado. Even though I'd been a full-fledged rock star for years by then, I still hardly even knew what cocaine was. I was unbelievably naive. I remember walking to the back of the studio one day, seeing a line of white powder on the table, and asking my manager, "What on earth is that?" He told me it was cocaine. I figured I'd take a little sniff.