In 1981, when brothers Gilbert and Jamie Hernandez self-published Love and Rockets it rocked the underground comics scene by introducing a genre-crossing artistic style (which would become known as magic realism), interconnecting stories, multicultural (particularly Latino) characters, strong women, positive gay and bisexual characters, and a focus on everyday people (rather than superheroes).

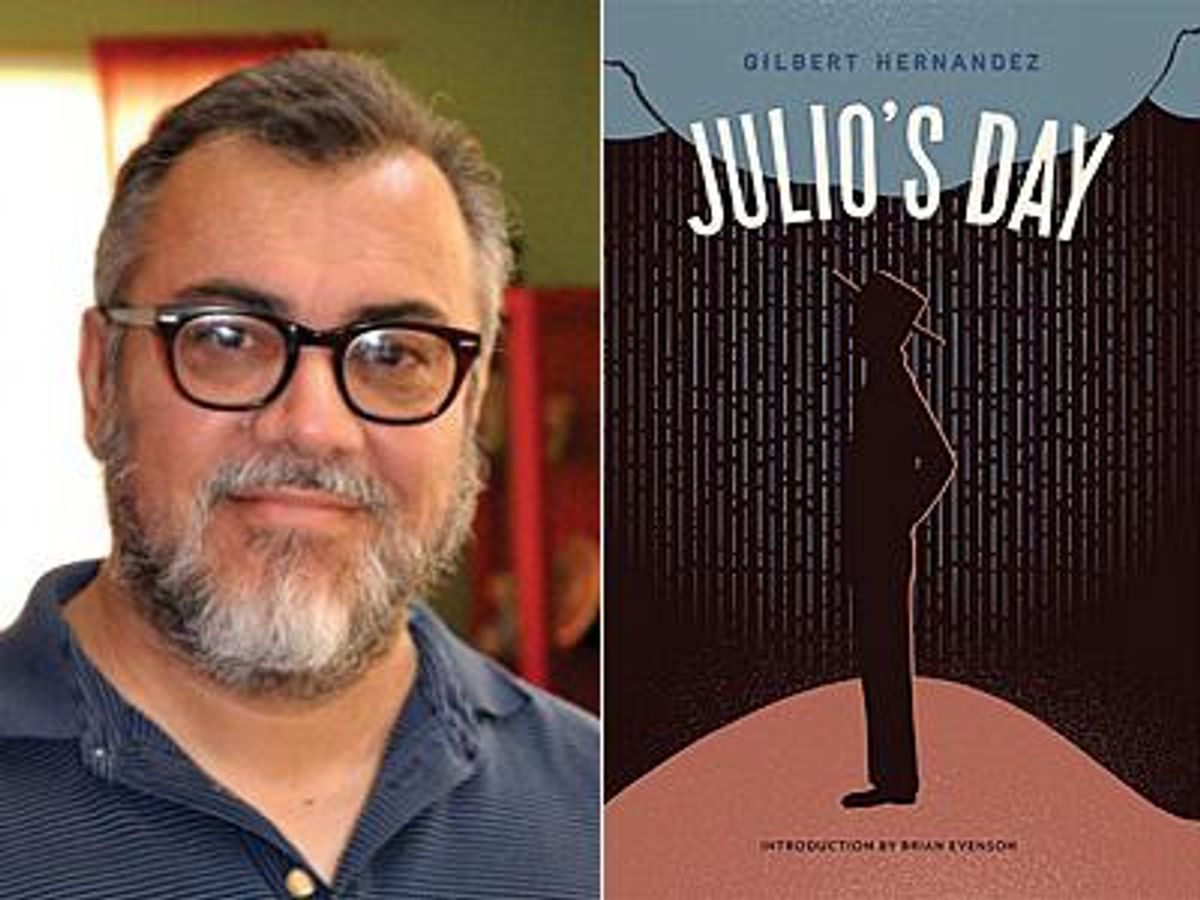

One Love and Rockets character, first introduced in Volume II, was Julio, whose storyline Gilbert Hernandez has now compiled and extended into a separate graphic novel, Julio's Day (Fantagraphics Books, $19.99), a brilliant graphic novel out in March, which compresses Julio's entire life into 100 pages.

The story begins and ends in complementary frames of black representing the nothingness which life both springs from and returns to. The blackness resolves into/fades from the open mouth scream of a newborn/dying old man. Starting with Julio's birth in 1900 and ending with his death in 2000, Julio's Day presents representative moments from Julio's life, moments that simultaneously illustrate both the micro and macro influences that impact Julio, his extended family, his close friends, and the larger world beyond his rural Southern Californian village.

The wars, diseases, natural disasters, great depressions, and revolutionary social/cultural changes of the 20th century generally happen off page, as they occur a world away from Julio's little village. Yet Hernandez is able to illustrate that those events had a global reach and dramatically impacted the lives of everyone -- including the people in Julio's life.

A remarkable accomplishment that is likely to find its way on numerous Best of 2013 lists and garner Hernandez more well deserved awards and accolades, Julio's Day is, at its heart, a gay story.

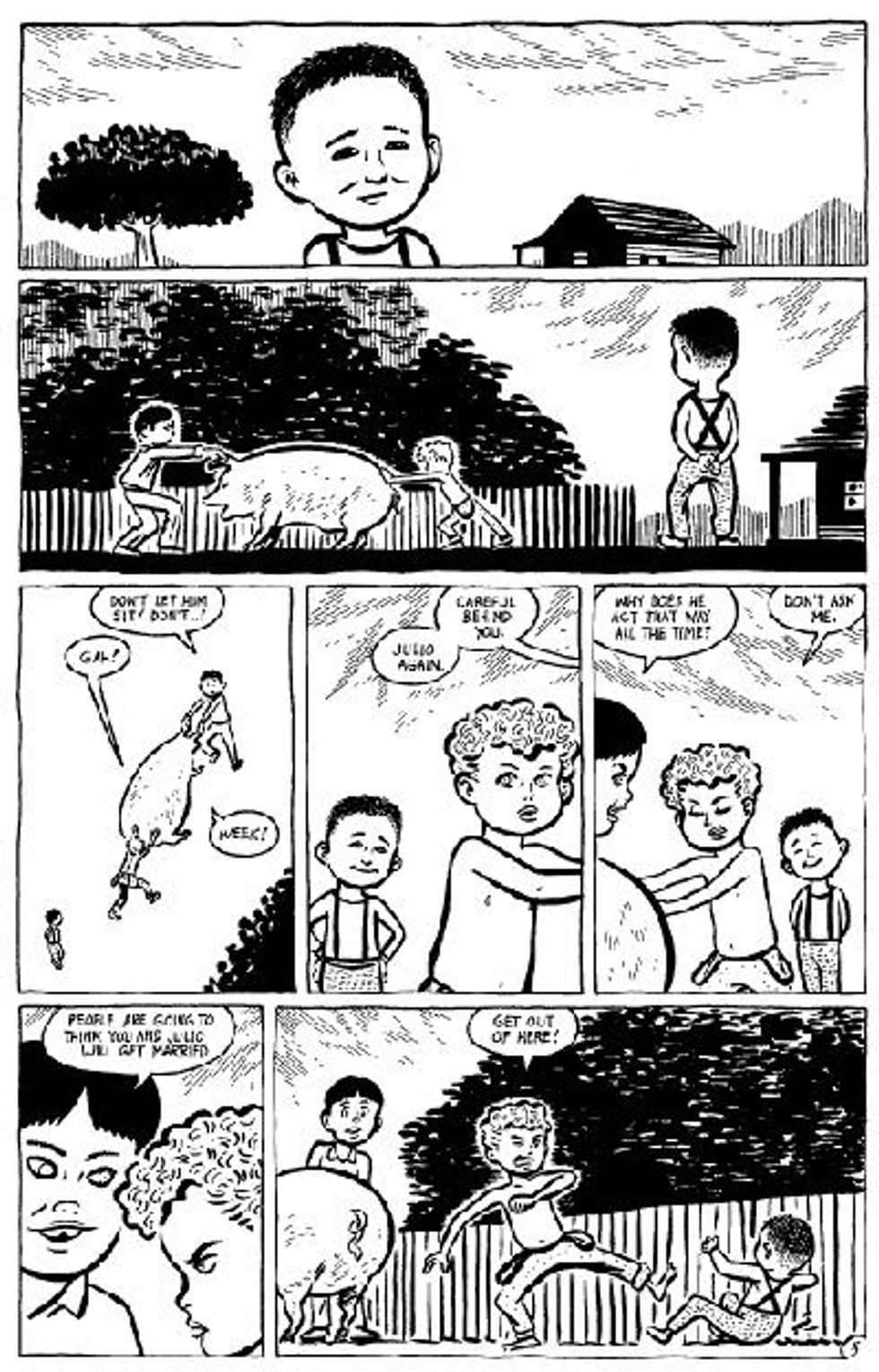

Julio is a gay man, but the kind of gay man who would never call himself gay. After all Julio is a man of his times, and -- in his day -- gay men often lived their entire lives in the closet. Julio never verbalizes his orientation and neither does Hernandez. Still, the artist/author is able to hint at same-sex encounters and gay love in the imagery and dialogue. Remarkably, the book includes no descriptive narrative; there are only images and dialogue to tell the reader what time period it is and what is going on.

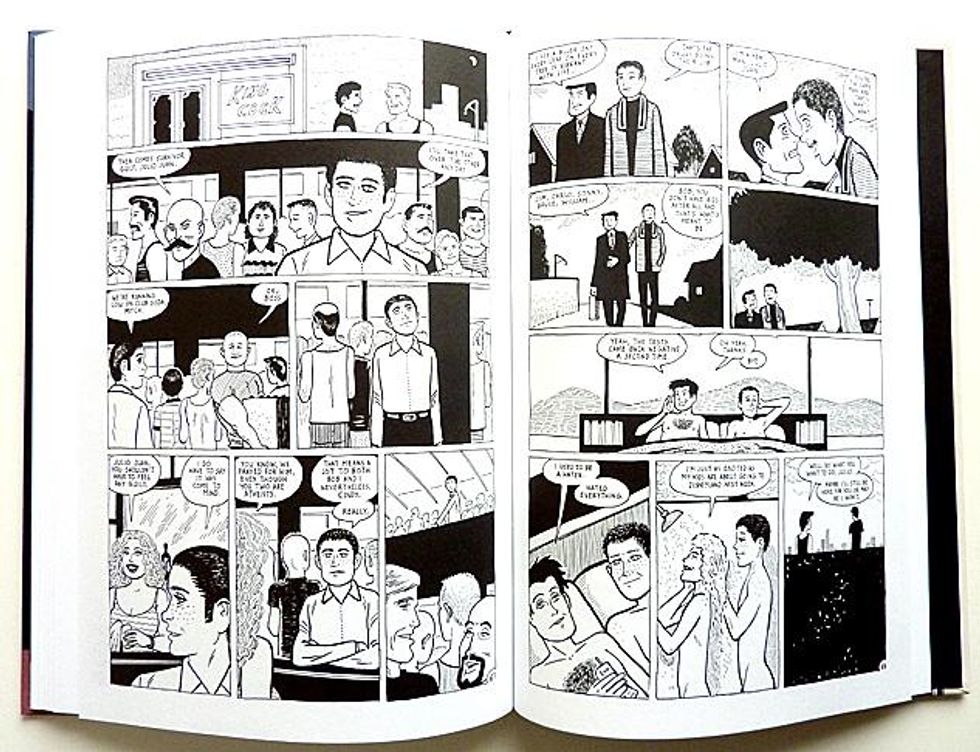

Julio reflects his time. But, as Julio's Day clearly demonstrates, times change. Thus, Julio's great, great nephew -- who not only shares Julio's name but his desire for men -- is presented much differently: his homosexuality is blatant. Hernandez explicitly illustrates his romantic and sexual encounters.

The differences between the older and younger Julio's is captured in this brief exchange:

"It's no secret that I sleep with men, Julio," says the younger man. "I'm not ashamed."

"Stop talking filth," elder Julio replies.

The younger Julio opens a gay night club and deals with the impact of AIDS, yet remains happy, well-adjusted and -- perhaps most importantly -- partnered as the story comes to an end. Meanwhile the older Julio dies in the same house where he was born, alone but for the woman who brought him into the world. His mother is there at both ends, to usher Julio in and out of his life.

Julio's day is past. It is now the younger Julio's day. And ours.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered