Andy Warhol's ode to male prostitution, Flesh, might never have been made if not for Midnight Cowboy. Then again, John Schlesinger's Oscar-winning movie about a Times Square hustler might never have been made if not for the world of Andy Warhol.

In the summer of 1968, Warhol was recuperating in New York City's Columbus Hospital after a near-fatal gunshot wound delivered by Valerie Solanas. Weeks before, Solanas had given him her feminist script "Up Your Ass" to read and hopefully make into a movie. But it was too downbeat, too lesbian for Andy's apolitical taste, and so pornographic that he thought the cops had planted it to trap him with an obscenity charge. Upset at his rejection, Solanas decided to pay him a visit at the Factory. When she rode the elevator up to the sixth floor at 33 Union Square West, Andy was talking on the phone to his superstar Viva, who was having her hair done only a few blocks uptown at Kenneth's Hair Salon.

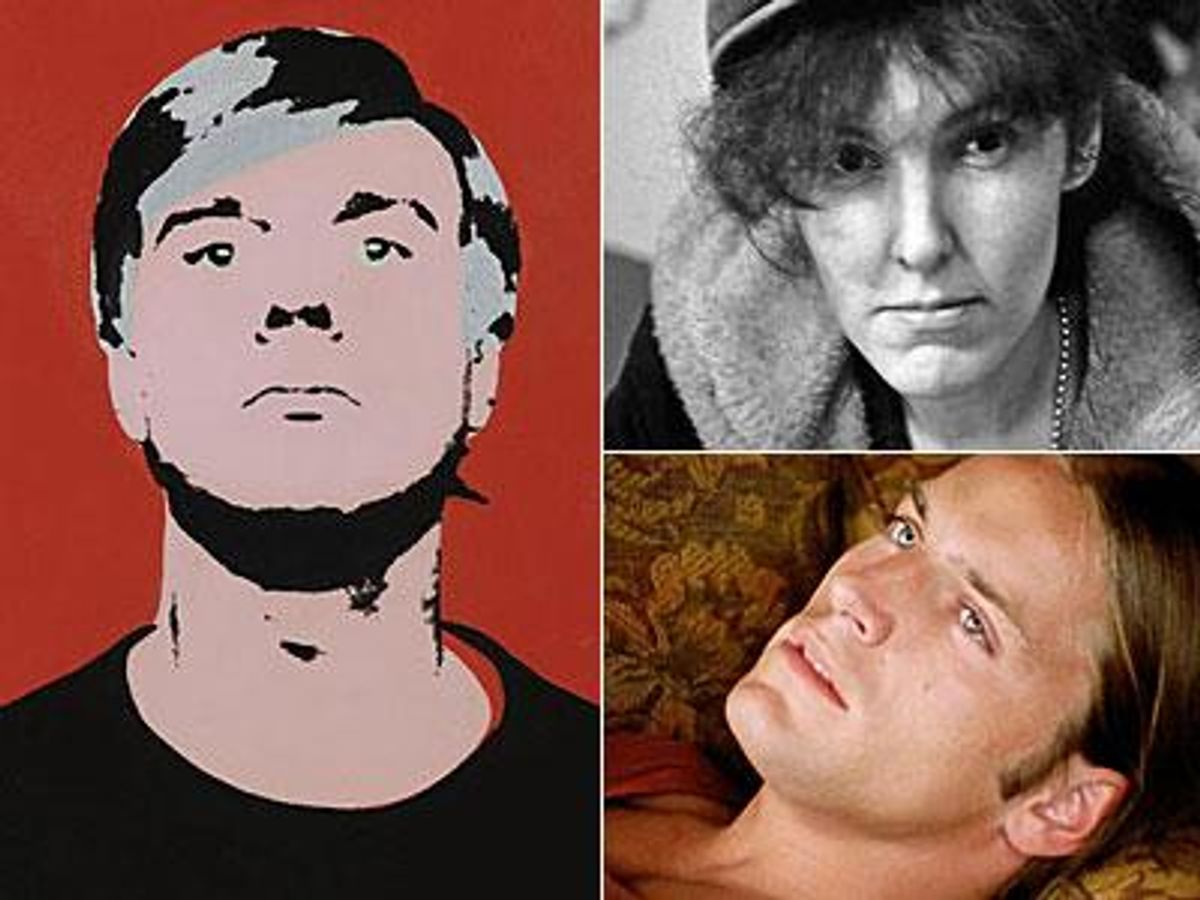

At left: Dustin Hoffman, Ultra Violet, and Viva in Midnight Cowboy

At left: Dustin Hoffman, Ultra Violet, and Viva in Midnight Cowboy

"Andy, Andy, I've got the part. I'm so thrilled!" Viva cried into the receiver. She didn't even have to tell him the name of the project. It was John Schlesinger's new movie, Midnight Cowboy, and Andy knew all about it and how screenwriter Waldo Salt had taken the James Leo Herlihy novel about a Times Square hustler and added his own subplot in which two Warholesque characters, named Hansel and Gretel, roam the streets of Manhattan looking for strange and photogenic people they can put into a Warholesque movie. Schlesinger wanted Andy to play himself in the movie. Andy passed on the offer but gave his blessing to Viva to play the cinema verite director, who, in effect, was him. Schlesinger's new lover, Michael Childers, had facilitated some of the casting since he was a good friend of Paul Morrissey, the real director of Warhol's movies. Childers recalled, "John and I had dinner with Paul and Andy at Max's Kansas City, and all the Warhol superstar speed freaks were there, along with Salvador Dali and Robert Rauschenberg."

Viva, excited about her new movie gig, had phoned Andy from Kenneth's, where she was having her hair dyed and frizzed for the role of Gretel. That's when she heard Andy scream, "Get that woman away from me!" Viva thought Andy was pretending, that they were making yet another movie at the Factory. Instead, he'd been shot, and surgeons at Columbus Hospital would have to work over his body for hours to keep him alive.

At left: Valerie Solanas

During the filming of Midnight Cowboy that summer, Viva channeled her Gretel filmmaker role, and, wielding a tape recorder, she never stopped asking everyone on the set, "Say something to Andy, who's in the hospital."

Viva's big moment in Midnight Cowboy is the party scene where Jon Voight's hustler Joe Buck arrives and Dustin Hoffman's tubercular friend Ratso Rizzo negotiates a deal for him to sleep with an uptown matron, played by Brenda Vaccaro. The party might have been screenwriter Waldo Salt's idea, but it was Michael Childers who enlisted the Warhol troops, including Viva, Morrissey and Ultra Violet. Morrissey, in turn, wrangled a few Factory hangers-on for the scene. "There were a few around in the back of the crowd and you couldn't see them," said Morrissey. "All the professional actor knew how to stay in front of the camera."

According to Childers, he and Morrissey shot an untitled short film in which Ultra Violet enacts being raped by a young blond boy. Schlesinger found it too graphic, but Childers told him not to worry. The film would be projected over the bodies of the partygoers, and nobody would be able to tell what the hell was going on.

"It was amazing. The party went on for three, four days," said Childers. "We weren't providing drugs."

Many of the extras, especially the Factory kids, brought their own pharmaceuticals. And there were other ways to indulge.

"It was like a six-day bacchanal. Pot in vast quantities," said the film's producer, Jerome Hellman. "And these kids, floating around, fucking in the toilets, fucking the dressing rooms, fucking in the wardrobe rooms. We had to establish certain characters, so we were worried about people not coming back. Boy, they were back. They couldn't wait to get back."

Hellman came aboard the project when Schlesinger's previous producer, Joseph Janni, backed out, calling the novel Midnight Cowboy "f****t stuff," and telling Schlesinger, "This will destroy your career."

Hellman came aboard the project when Schlesinger's previous producer, Joseph Janni, backed out, calling the novel Midnight Cowboy "f****t stuff," and telling Schlesinger, "This will destroy your career."

Hellman, for his part, called it "a very powerful story."

The crew on the film agreed with Janni. "The technicians were a tough New York group who regarded me with some suspicion," said Schlesinger. "I think they thought we were making a sleazy film."

Childers felt that the crew worked in a state of "total shock and disgust at the movie." When they weren't wishing out loud, "We should be working on a Neil Simon picture," they rubbed their beer guts and tsked, "We've never seen anything like this!"

What disgusted the crew is what attracted Dustin Hoffman to Midnight Cowboy. After his breakthrough film, The Graduate, he wanted a role completely different, and he reveled in his character's possible homosexuality. For example, in the film Joe Buck and Ratso Rizzo live in the same abandoned apartment. One day, Schlesinger gave his two actors a bit of direction. "All right, Dustin's going to be on the floor and Voight's going to be on the bed."

Hoffman, however, wasn't buying it. "We're not just roommates, we're lovers. Why aren't we in bed together, they're lovers."

Schlesinger shook his head. "I'm sure they are, but you try and get this film financed."

Schlesinger shook his head. "I'm sure they are, but you try and get this film financed."

Andy Warhol (pictured left), still recuperating, heard some of these reports, especially those regarding the party scene in Midnight Cowboy. He was both intrigued and stressed by what he heard.

Maybe if he'd accepted Schlesinger's offer to play the underground filmmaker in the movie, then he, rather than Viva, would have had his silver wig coiffed. Instead, he'd been nearly murdered by Valerie Solanas. And it bothered him that his whole persona, scene, shtick, and entourage of superstars were being used without any compensation to him.

"Why did they give us the money?" he asked Morrissey. "We would have done it so real for them." Andy meant the party, not the rape movie with Ultra Violet and the blond boy.

Midnight Cowboy did give Andy an idea, maybe even two ideas, if both of them didn't originate with Morrissey. If Schlesinger could rip off their world, they could in turn appropriate his. Their cowboy movie, shot in January and starring Viva, still languished without a title or a theater. Maybe if they called it Lonesome Cowboys audiences would confuse it with Schlesinger's title. And better yet, maybe they could make another film, one that would be a portrait of a male hustler, like Midnight Cowboy, and quickly get it into theaters to beat Schlesinger at his own game.

"I vaguely knew what they were doing with Midnight Cowboy," said Morrissey. "When I had a chance to do Flesh, I thought, I'll do something like Midnight Cowboy, but I didn't know how Midnight Cowboy was handling the subject."

"I vaguely knew what they were doing with Midnight Cowboy," said Morrissey. "When I had a chance to do Flesh, I thought, I'll do something like Midnight Cowboy, but I didn't know how Midnight Cowboy was handling the subject."

Morrissey thought he had a new superstar in this kid who'd appeared briefly in Lonesome Cowboys. Joe Dallesandro wasn't like the other superstars at the Factory. He wasn't weird or show-offy or even gay. In the following decade, the legendary film director George Cukor would say of him, "Joe Dallesandro does some enormously difficult things...like walking around in the nude in a completely unselfconscious way."

In Morrissey's Flesh, Dallesandro would be naked a lot in his role as a male prostitute whose bisexual wife needs him to earn two hundred dollars to pay for her girlfriend's abortion. It wasn't all acting for Dallesandro, who supported himself for a time by posing nude for pseudo-gay publications like Athletic Model Guild. He didn't hustle, but he knew the scene. "When you're young and beautiful, you do get a lot of propositions," he said. "I always said it wasn't about a hustle. It was about how you got people who wanted to be a part of your life. The pay was that they became a part of your life, even if for a short time."

In the hothouse world of the Factory, Dallesandro came off lot a breath of heterosexual air. But he never denigrated the homosexuals who flocked around him. "If it hadn't been for the gay men and how well they treated me, I would have killed somebody," he claimed.

"Joe was not an improviser," said Morrissey. "He was a quiet person, the eye of the storm, and this lunacy going on around him therefore became very dramatic."

Andy described Dallesandro's appeal even more succinctly. "Everybody loves Joe," he said.

Andy described Dallesandro's appeal even more succinctly. "Everybody loves Joe," he said.

Sometimes it seemed everybody at the Factory wanted to see Joe naked, too. "There was always a reason to take my clothes off," said Dallesandro. "I was very young. What are we doing? I was uncomfortable." But he never showed it - not on camera, anyway.

Morrissey filmed Flesh over a period of six weekends at friends' apartments in New York City. The budget: $3,000.

Still stationed at Columbus Hospital, Andy broke out laughing when actress Geri Miller told him how her striptease in the film so turned Joe on that he got aroused and she tied a big bow around his erection. It was all improvised, like everything in the movie, and Morrissey obliged by keeping the camera running.

True to plan, Andy opened Flesh that autumn at the Garrick Theatre in Manhattan while John Schlesinger continued to edit Midnight Cowboy. The little picture did very well for itself, playing the Garrick for seven months and grossing an average of $2,000 a week on its $3,000 budget. Morrissey was surprised that the erection footage didn't cause censorship problems; maybe it even disappointed him. At his urging, friends phoned the police to complain.

"He'd have these plants go in and do this. It was just to get all this publicity and coverage, and it worked," said Dallesandro.

At left: Brenda Vacarro and Jon Voight in Midnight Cowboy

At left: Brenda Vacarro and Jon Voight in Midnight Cowboy

Later that year, Schlesinger finally had a rough cut of Midnight Cowboy to show to the executives at United Artists. Just before he and Jerome Hellman entered the screening room at the West Fifty-Fourth Street Movie Lab, the director stopped to ask his producer, "Do you honestly believe anyone in their right mind is going to pay to see this rubbish?"

Surprisingly, the UA execs loved the movie, even when the newly created Motion Picture Association of America slapped it with an X-rating. And it didn't stop with the X. At the film's premiere on May 25, 1969, novelist James Leo Herlily took the opportunity at the after-party to complain about a couple of scenes that he demanded be excised, especially "the deviate act in the balcony of the movie theater," he said, referring to the scene where Bob Balaban's character performs fellatio on Joe Buck. "They invented it, and it was hard to watch and totally unnecessary."

Soon, reporters began taking their cues from Herlily. "We filmed two homosexual sequences which are explicit in the novel, and this is the only question that the press seemed interested in," said Schlesinger, who noted a distinct "hostility" in the press's coverage of the movie.

None of which deterred the voters at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from giving Midnight Cowboy seven Oscar nominations, including ones for best picture and director. However, the Academy officials didn't like one of their nominated pictures being sullied with an X-rating. The MPAA announced that it would give Midnight Cowboy the less restrictive R rating -- if Schlesinger cut the Balaban/Voight blowjob scene.

Schlesinger kept it simple. "No way," he said.

His tenacity paid off. Midnight Cowboy won the best picture Oscar, and Schlesinger was named best director. Rather than attend the ceremony in Los Angeles, he decided to stay in England to continue work on his new film, Sunday Bloody Sunday. Schlesinger got the good news at 5 a.m. in London.

"We screamed in our pajamas!" Michael Childers recalled.

From the book Sexplosion! Copyright 2014 by Robert Hofler. Reprinted by permission of It Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Robert Hofler is the theater critic for The Wrap and lives in New York City. In addition to Sexplosion! his books include the Henry Willson bio The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson and the Allan Carr bio Party Animals. He will be speaking at the New York LGBT Center April 8 at 7 p.m. as part of the center's Second Tuesday Lecture Series. Find more information here.

At left: Dustin Hoffman, Ultra Violet, and Viva in Midnight Cowboy

At left: Dustin Hoffman, Ultra Violet, and Viva in Midnight Cowboy

Hellman came aboard the project when Schlesinger's previous producer, Joseph Janni, backed out, calling the novel Midnight Cowboy "f****t stuff," and telling Schlesinger, "This will destroy your career."

Hellman came aboard the project when Schlesinger's previous producer, Joseph Janni, backed out, calling the novel Midnight Cowboy "f****t stuff," and telling Schlesinger, "This will destroy your career." Schlesinger shook his head. "I'm sure they are, but you try and get this film financed."

Schlesinger shook his head. "I'm sure they are, but you try and get this film financed." "I vaguely knew what they were doing with Midnight Cowboy," said Morrissey. "When I had a chance to do Flesh, I thought, I'll do something like Midnight Cowboy, but I didn't know how Midnight Cowboy was handling the subject."

"I vaguely knew what they were doing with Midnight Cowboy," said Morrissey. "When I had a chance to do Flesh, I thought, I'll do something like Midnight Cowboy, but I didn't know how Midnight Cowboy was handling the subject." Andy described Dallesandro's appeal even more succinctly. "Everybody loves Joe," he said.

Andy described Dallesandro's appeal even more succinctly. "Everybody loves Joe," he said. At left: Brenda Vacarro and Jon Voight in Midnight Cowboy

At left: Brenda Vacarro and Jon Voight in Midnight Cowboy