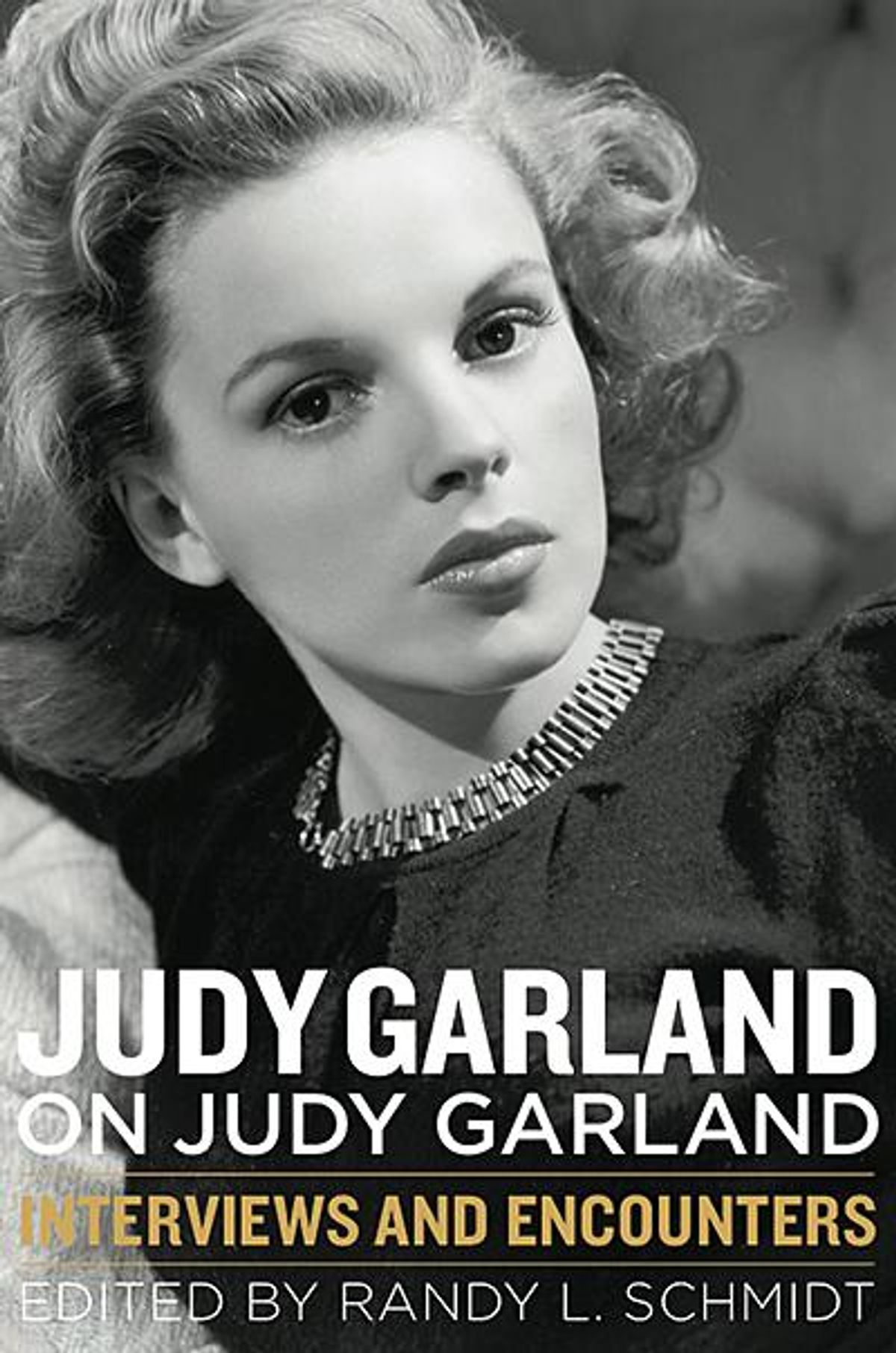

If you are a fan of a certain age, Judy Garland was the epicenter, the first real diva in a gay man's life. Certainly her ups and downs and triumphs and failures have been documented and rehashed and then sold to television (see Andrea McArdle in Rainbow). But to hear or read Judy in her own words is so revealing and wipes away any visions of her as frail or weak-willed. Judy Garland on Judy Garland, edited by Randy L. Schmidt, is the closest we will likely come to experiencing and exploring the legend's abandoned autobiography.

This collection of interviews between 1935 and 1969 traces the complicated trajectory of her star. Judy was a great storyteller, and in these interviews her talents come through as we get to sit dazzled at her feet as her stories spin. One of the most interesting interviews from the book is more of a dialogue between the gay megatalent Noel Coward and Judy as they compare their experiences in the spotlight. And these are real showfolk -- the word "darling" is uttered no less than 25 times in this interview. Here it is provided via the book's publisher:

A REDBOOK DIALOGUE: NOEL COWARD & JUDY GARLAND

November 1961, Redbook

What originated as a reporter's tape-recorded interview with playwright Noel Coward became a fly-on-the-wall look into a fascinating friendship. It was during the week of August 11, 1961, that Judy traveled with Kay Thompson and publicist John Springer to attend a preview of Coward's Sail Away at Colonial Theatre in Boston. Peppered with various exclamations by Thompson (the woman responsible for introducing the two), the conversation between Judy and Noel was taped the following day and later edited for Redbook.

They seem poles apart: America's Judy Garland, who can warm 50,000 hearts singing familiar songs in a huge, open stadium, and England's Noel Coward, who acts, writes and directs his own sophisticated plays and musical comedies. But they are devoted friends, and deep admirers of each other's talent. They are equally outspoken about the theater, the public, and life backstage, which they discuss with unusual honesty in the following dialogue tape-recorded in Boston shortly after the opening of Coward's new musical Sail Away.

NOEL COWARD: Let's just -- before we start talking -- decide what is interesting about you and me, Judy. I'd say it's first of all that we're very old friends, so that takes care of itself. What is interesting about us both is (a) you are probably the greatest singer of songs alive, and I ... well, I'm not so bad myself when I do my comedy numbers, and -- let's see, what else?

JUDY GARLAND: And (b), Noel, is that we both started on the stage at about the same age, didn't we?

NC: Yes. How old were you when you started?

JG: I was two.

NC: Two? Oh, you've beaten me. I was ten. But I was --

JG: What were you doing all that time?

NG: Oh ... studying languages! No, I started at the age of ten in the theater, but before that I'd been in ballet school. I started in ballet.

JG: You were going to be a dancer?

NC: Yes. I was a dancer for quite a while. Fred Astaire designed some dances for me in 1923. I was older than ten then, of course.

JG: How marvelous! I didn't know that! Did Fred--

NC: I don't think he was very proud of the dances, because I don't think I executed them very well. There was a lot of that cane-whacking tut-tumti-ti-tum in them.

JG: But, to go back, where did your theater ... Did you have any background? Was there anyone else in your family at all that was --

NC: Theaterly?

JG: That's it ... theaterly.

NC: No theater. Navy.

JG: No theater? How --

NC: We didn't know anything about it. My father's attitude was always one of faint bewilderment. But my mother loved the theater, you see, and she took me to my first play when I was five years old. It was my birthday treat. Every sixteenth of December I used to be taken to a theater. And then I was given a toy theater for Christmas.

JG: By your mother?

NC: By my mother. She adored -- she loved the theater, you see.

JG: Yes. Yes!

NC: And I was wildly enthusiastic about it and so that's how it all started. I had a perfectly beautiful boy's voice, so I was sent to the Chapel Royal School, where I trained to be ready for the great moment when I gave an audition for the Chapel Royal Choir, which is a very smart thing to be in. I did [Charles] Gounod's "There Is a Green Hill Far Away," and I suppose the inherent acting in me headed its ugly rear, because I tore myself to shreds. I made Maria Callas look like an amateur. I did the whole crucifixion bit -- with expression. The organist, poor man, fell back in horror. And the Chapel Royal Choir turned me down because I was overdramatic.

JG: (laughing): That's divine!

NC: Then Mother was very, very cross and said the man who had turned me down was common and stupid anyway. After that we saw an advertisement in the paper that said they wanted a handsome, talented boy, and Mother looked at me and said, "Well, you're talented," and off I went to give an audition. That's how I got on the stage.

JG: Divine! But it was different for me. I came in with vaudeville. I ... You know, it was sort of rotten vaudeville, not good vaudeville. I told you this once before, I think. I came in after the real great days and before television. Really, it was awful vaudeville, you know, so there was nothing very inspiring. But my children are being exposed to all the best.

NC: Of theater?

JG: Yes. I want them to be exposed to it. I think it's rather stupid to be involved in making movies or whatever, and just leave your children every morning --

NC: "Mother's going out now."

JG: Yes, and say, "I'm going to work now, but you mustn't know where because I don't want you exposed."

NC: Well, also the children might adore being exposed. Why not enjoy themselves?

JG: So I take them along with me. They have been on movie sets. They have been backstage in the wings. They know what I do when I go to work. Sometimes I think that actresses who say they don't want their children exposed to publicity and don't want their children photographed ... Well, I have a strange, uncanny feeling that maybe Ma doesn't want any attention taken away from her, you know?

NC: You can't have secrets from them. If your mother happens to be an actress, you've got to take it on the jaw and understand that you're the daughter of an actress. ...

NC: You can't have secrets from them. If your mother happens to be an actress, you've got to take it on the jaw and understand that you're the daughter of an actress. ...

JG: And you know, it isn't a bad atmosphere. It's fun for our children to go to the theater. And I think that as long as I have a good relationship with them and our home life is a good one, the entertainment world can't possibly hurt them. I don't know whether any of them will become entertainers or not. We'll see. My oldest daughter, Liza, is talented and sort of stuck on the business.

NC: I'd love to see Liza.

JG: She started to dance when she was five.

NC: And you encouraged it?

JG: Yes. And she's a brilliant dancer, really. But now she has grown up with the best of -- of talents. She has seen you. Her father, who is a very, very talented man, has exposed her to the best of the theater, so she does have taste and she does have a talent. Now she's in summer stock. My other daughter, Lorna -- she's eight -- is the Gertrude Lawrence of Hyannis Port. She's just impossible, and the most beautiful creature who has ever lived, I think. And she's so shocking and bright and cunning and hep. She's such a great actress that we don't know what we're going to do with her. We really don't. I'm sure she's going to turn into something important. I don't have any idea at all what it will be, but it will be startling and flamboyant and -- But I'm taking over the whole darn conversation.

NC: No, darling, you should.

JG: It's funny how Liza is so much like me, a quietness much of the time, a little sedentary, and Lorna is just the opposite, a mercurial child.

NC: When I saw you first, Judy, you were a little girl, although you talk about the vaudeville and all those things ... But of course, that is the way to learn theater, and not acting school -- playing to audiences, however badly.

JG: Trial and error. Trial and error.

NC: Whenever I see you before an audience now, coming on with the authority of a great star and really taking hold of that audience, I know that every single heartbreak you had when you were a little girl, every number that was taken away, every disappointment, went into making this authority.

JG: Exactly. Exactly, and it's all -- it sounds like the most Pollyanna thing to say, but it is truly worth it -- the heartbreak and the disappointments -- when you can walk out and help hundreds of people enjoy themselves. And this is only something you can learn through trial and error.

NC: Nobody can teach you ... no correspondence courses, no theories, no rehearsals in studios.

JG: No, you can only learn in front of an audience.

NC: And if there are people who cannot withstand these pressures, and if they are destroyed by these pressures, then they are simply no good and are just as well destroyed.

JG: Do you really mean that, darling? What do you mean?

JG: Do you really mean that, darling? What do you mean?

NC: Well, my dear, the race is to the swift. In our profession the thing that counts is survival. Survival. It's comparatively easy, if you have talent, to be a success. But what is terribly difficult is to hold it, to maintain it over a period of years. You see, nowadays, when everything is promotion and the smallest understudy has a personal manager and an agent rooting for her and a seven-year contract with somebody, they don't take the time to learn their jobs. Then after their first success they run into difficulty -- they have personal problems. And when public performers allow personal problems to interfere with their public performances, they are bores.

JG: Yes, and if they're haunted and miserable off stage, they are still bores. Because they are entertainers, and entertainers receive so much approval and love -- and for heaven's sake, that's what we're all looking for, approval and love. And they receive it every night and in every way. If they are good, they receive adoration, applause ...

NC: Applause, cheers, flowers.

JG: And if they insist on leaving the stage and going -- Well, I did this for many years. I was the most awful bore. I went offstage and I'd go into my own little mood and remember all the miserable things and how tragic it was -- and it wasn't tragic at all, really. I was just a plain bore. And I think anybody who clings to this tragic pose is a poseur -- a phony.

NC: Self-pity.

JG: It's self-pity, and there's nothing more boring than self-pity.

NC: And it's a very great temptation -- particularly when you're a star and you know that you have an enormous amount of responsibility, you are liable to fall into the trap of self-pity. If somebody doesn't please you or something goes wrong, you fall into the trap -- you make a scene, which is quite unnecessary. If you're an ordinary human being working in an office every day, you wouldn't behave like that. No, an entertainer has to watch his legend and see that he stays clear and simple.

JG: But you've always done this, Noel. Now, I've known you for years. You've always done this. You are a terribly wise man who in spite of many facets of talent and brilliance and so forth has kept your mind in complete order and your emotions in order. You have great style and great taste. Weren't you ever inclined to fall into a sort of self-pity?

NC: Oh, yes, yes, yes.

JG: Oh, good. It makes me feel much better, because I really did it for a long time.

NC: After all, Judy, darling, I'm much older than you.

JG: Not much anymore, darling. Nobody is.

NC: I've been in the theater fifty-one years, and all my early years were spent in understudying, in touring companies and everything. But then I had my first successes, and they came when I was terribly young. I was only in my early twenties. The Vortex opened in London on my twenty-fifth birthday. After that I went through a dangerous phase. Suddenly everything I did became a great success. I didn't realize what danger I was in. I had made this meteoric rise, I had five plays running, I was the belle of the ball--and they got sick of it. And I got careless. I thought it was easy to be a success, and it's never easy.

JG: No. No, it never is.

NC: I wrote one or two things that weren't so good. And at the age of twenty-seven I found myself booed off the stage by the public on an opening night, and outside the stage door someone spat at me. That was a shock. It didn't hurt me, though. I was rather grateful for the bitter experience, for being shown I wasn't quite as clever as I thought I was.

JG: You were grateful to the public?

NC: Yes, they judge what they see -- and it's up to me to make them see what I want them to see. Now, for instance, last night [the Boston opening of Noel Coward's new play, Sail Away] they came into that theater and they got a first impression. I had everything on my side. I had an extremely good cast, very good orchestra, wonderful choreography --

JG: And very good music and very good material, darling.

NC: Which I'm very proud of. But what was wrong with it -- and I know this -- was, there are certain moments when it needs tightening. There are certain numbers that occur here when they should occur there. The first part of the play goes too long without an up number. There are a whole lot of lines that might have been hilariously funny but didn't get over, and with two good audiences. So now those lines will be cut, that's what.

JG: Gosh, I didn't -- I may sound stupid, but I don't remember a good line that anybody missed.

NC: There wasn't a good line that anybody missed. It was the bad lines. (He laughs.)

JG: I don't remember a bad line.

NC: Tonight I shall sit in that theater with my secretary and make a note of every line I'm going to cut, and I should think there'll be over fifty. I've already cut four scenes and three big numbers.

JG: My God, you're a pro! And that's what's important. You have to know how to make people feel how you want them to feel. That's the challenge. That part that I took in Judgment at Nuremberg is a wonderful, wonderful role. It will probably last only about eight minutes on the screen, but what happens in those eight minutes is important, and it was challenging. The whole feeling was challenging -- Stanley Kramer, the director, and Spencer Tracy, and a great script. I've always wanted to work with Stanley Kramer. I have a great admiration for him. Why does an actress take a part like that? Because the correct people are involved. Much more important than billing and starring.

JG: My God, you're a pro! And that's what's important. You have to know how to make people feel how you want them to feel. That's the challenge. That part that I took in Judgment at Nuremberg is a wonderful, wonderful role. It will probably last only about eight minutes on the screen, but what happens in those eight minutes is important, and it was challenging. The whole feeling was challenging -- Stanley Kramer, the director, and Spencer Tracy, and a great script. I've always wanted to work with Stanley Kramer. I have a great admiration for him. Why does an actress take a part like that? Because the correct people are involved. Much more important than billing and starring.

NC: Billing and starring are the two most boring words in the lexicon. As long as when you're up there you do it right.

JG: You were certainly the star last night [at a party for cast and friends after the opening of Sail Away].

NC: Thank you, darling. There were far too many people there. But I was slightly proud that they had taken that picture of me looking like a very old bull moose and put it up in place of the portrait of George Washington. In Boston, of all places! Considering the Boston Tea Party, this was really very kind of them. I imagine they've forgiven us for that now.

JG: (laughing): At least you've been forgiven.

NC: I was absolutely exhausted. I've been working frightfully hard these last few weeks -- we had been rehearsing during the day -- and then opening night. The first night is always an ordeal. However successful you are, you're always nervous that first night. But it went wonderfully and I was very happy. I came back to the hotel, washed my face and hands, had a drink and then I thought, Now, this must be done properly because everybody is coming to the party. It's my turn to give a performance -- at midnight. Then you came. And you stopped being Judy and became Judy Garland. And I was no more Noel. I was Noel Coward, debonair, witty, charming and ...

JG: ... and I was Dorothy Adorable.

NC: And you were just Dorothy Adorable, and we smiled and we took the show. And there we both were, together with a lot of people who stood around waiting for us to be charming and clever and entertaining. We were such good sorts. My dear, going on being such good sorts in public for a long time is very wearing, because we weren't feeling really in good sorts at all. What we wanted to do is get away and ...

JG: and put on some slacks and sprawl out on the floor.

NC: ... put on some -- take off our shoes and have a drink and discuss show business. That's what is really interesting. In all the concerts I did for the troops during the war, the only thing I dreaded was the party given after the show by the commanding officer. I might have done five concerts in a day in the heat of Burma, but the officers would still expect me to come to their party. And then, after giving me a couple of drinks to help me relax, they would come out with it: "How about giving us a few numbers?" You want to clobber them. You're dead. But you say yes.

JG: You do it. You do it.

NC: You do it. And you go home screaming.

JG: I'm getting so [old] I wonder why I do it anymore. But I still do. I suppose it's something we never --

NC: We're show people.

JG: I suppose. Once in London, I remember, I was invited to a party. First I had to do some recording, and it took hours. I had five or six recordings, and you know that means doing them over and over -- and I sing terribly loud. It was late, and I called and said I'd be late for the party. When I finally arrived, I found that everybody had already eaten and just the leftovers were still on the table -- you know, awful bits of cold ham and wilted lettuce. I was so hungry that when the hostess brought me a miserable looking plate, I started eating. "Now," she said, "Kay [Thompson] is at the piano, and everybody's been waiting for you to sing." I said, "I've just been singing for five hours, you know" But what could I do? Kay and I sang for another three hours. Then we went home on our hands and knees. Just so tired. But the people really were standing like statues and they had been there all evening.

NC: They get it for nothing. Getting it for nothing. They say, "Wouldn't it be wonderful if we could persuade her to sing?" That's all right. That's fine. But what is irritating is to be taken for granted, when they expect you to perform come hell or high water. With or without an accompanist, whether or not you've just finished working, you are expected to sing. And as soon as you start -- everybody starts to talk.

JG: Oh, darling, they don't do that to you too!

NC: I'll tell you one little story that happened during the war. I came back to Cairo after a long, hot day entertaining in one hospital after another, and I found a message saying King Farouk was giving a party that evening and would I please come? So I obediently had a shower and got into a white dinner jacket and went off to one of the most boring social affairs imaginable. My eye caught a very nasty-looking upright piano, and I thought, Hello, hello -- this is it! And King Farouk, covered in medals, came up and asked me very courteously, "Mr. Coward, would you sing us a few songs?" I thought it discourteous to say that I don't like playing for myself while I sing, so I agreed. I went to the piano and sang a number and everyone was fairly attentive but restless. Then I started on "Night and Day" -- I can play it well and I've got a good arrangement. And I did the drip-drip-drip of the raindrops and all the rest, with everyone quiet except King Farouk, who was busy impressing the lady next to him. He was so rude that I lost my temper. So I got to the chorus and sang, "In the roaring traffic's boom" and then I went, "In the SILENCE!" He stopped dead, and there was a terrible hush, and then I continued blithely, "of my lonely room, I think of you."

JG: (laughing): Lovely!

NC: In the old days, when we entertainers were considered rogues and vagabonds and we weren't received socially--which of course saved us an enormous amount of boredom -- we were bloody well paid for performing. We might be shown in through the servants' quarters, but that was all right. You'd sing your song and get five hundred quid for it.

JG: When I was at Metro -- I don't think I was much over twelve years old, and they didn't know what to do with me because they wanted you either five years old or eighteen, with nothing in between. Well, I was in between, and so was little Deanna Durbin, and they didn't know what to do with us. So we just went to school every day and wandered around the lot. Whenever the important stars had parties, though, they called the casting office and said "Bring those two kids." We would be taken over and we would wait with the servants until they called us into the drawing room, where we would perform. We never got five hundred quid, though. We got a dish of ice cream -- and it would always be melted.

NC: But I'm talking about the ... the big stars now -- not kids. In the old days the big stars were common trash, however big the star.

JG: With certain groups I still feel that I'm being taken up as a kind of -- you know, sort of, oh, it's fun with Judy Garland. She's fun! She sings! You feel you're being used as a kind of foolish court jester who'll be dropped next season when the newest property comes in.

NC: Oh, yes, and after you've done your number, darling, without any rehearsal and no lighting and no rest, someone says, "My, doesn't he look old."

JG: (laughing): Or fat.

NC: But, of course, it is no use ever expecting society to understand about show business or entertainers because they never do, do they?

NC: You can't have secrets from them. If your mother happens to be an actress, you've got to take it on the jaw and understand that you're the daughter of an actress. ...

NC: You can't have secrets from them. If your mother happens to be an actress, you've got to take it on the jaw and understand that you're the daughter of an actress. ... JG: Do you really mean that, darling? What do you mean?

JG: Do you really mean that, darling? What do you mean? JG: My God, you're a pro! And that's what's important. You have to know how to make people feel how you want them to feel. That's the challenge. That part that I took in Judgment at Nuremberg is a wonderful, wonderful role. It will probably last only about eight minutes on the screen, but what happens in those eight minutes is important, and it was challenging. The whole feeling was challenging -- Stanley Kramer, the director, and Spencer Tracy, and a great script. I've always wanted to work with Stanley Kramer. I have a great admiration for him. Why does an actress take a part like that? Because the correct people are involved. Much more important than billing and starring.

JG: My God, you're a pro! And that's what's important. You have to know how to make people feel how you want them to feel. That's the challenge. That part that I took in Judgment at Nuremberg is a wonderful, wonderful role. It will probably last only about eight minutes on the screen, but what happens in those eight minutes is important, and it was challenging. The whole feeling was challenging -- Stanley Kramer, the director, and Spencer Tracy, and a great script. I've always wanted to work with Stanley Kramer. I have a great admiration for him. Why does an actress take a part like that? Because the correct people are involved. Much more important than billing and starring.