It is the mid-nineties and multicultural everything is in. I have the books, the teachers, and the new friends to teach me that being queer is about as normal as me being a Latina at a predominantly white college. Sure, Latinas and queers are outnumbered, but now the laws are on our side, and we have a small but visible community.

The more I listen to Fanny talk about her life with a woman, the more comfortable I also feel. She knows about Audre Lorde and arroz con frijoles, and she throws a Spanish word into the conversation every now and then. She is close enough to remind me of home, the equivalent of my mother and aunties in one woman, with the lesbian and feminist parts added.

The worst part about trying to date women is that I don't have my mother's warnings. There is no indicator if I am doing it right or wrong. And so, my queer friends and the spoken-word artists in New York are my teachers, and they know the formula.

Sleep with your friend, sleep with her friend.

Break up and get back together again.

Write her a poem, show her the piers, pretend you want less than you do.

One-night stands, one-night nothing.

You'll see her at Henrietta's again and again.

My friend is Dominican. When we make love, I can't tell what's more exciting: her large, naked breasts against my own B-cup-sized ones or the inversion afterwards of gender roles. I am now the one buying dinner, picking up the flowers, driving us upstate. Every time she mixes Spanish and English in the same sentence, a part of myself collapses into what I am sure is eternal love.

Within months, however, the relationship sours. So, I try dating another friend. She e-mails that she isn't interested.

I go out with a Puerto Rican butch, who drinks about as many Coronas as my father. My mother and aunties would be horrified. I am too, after two months.

I meet another Dominican femme, but this one drives an SUV, has her hair straightened once a week, and keeps a butch lover in the Bronx. After three times in bed, I get tired of being on top.

Dating a transgender man, I get tired of being on the bottom.

I go back to what I know and try dating a Colombian woman. But she lives across the Hudson River and doesn't have a phone with long distance.

I persevere though--drinking flat Diet Coke at lesbian bars and giving women my phone number--because I do not believe my mother. I have read the romance novels, seen the movies, and heard the songs. Love will work no matter what job I have, what nationality I claim, or what street I want to live on. It will work even if I kiss a woman.

And it does.

For a few months, I fall in love with a dark-haired woman who has a way of tilting her bony hip that gives her ownership of the room. Men hit on Lisette and she snaps, "I don't think my girlfriend would appreciate that." She is the most feminine woman I have dated (hours are spent dabbing eye shadow in multiple directions), but also the most masculine. She carries my bags, buys me overpriced jeans, leans in to kiss me. She talks to me about the films she will make one day and the books I will write. She follows me into the dressing room at Express and whispers that she wants to go down on me right there. "I like it when you scream," she tells me in bed. "I need you to do it like this morning. Scratch my back when I'm fucking you."

I had heard those lines before from men and from women, but it's different this time. I am sure I will never date anyone else ever again.

When she breaks up with me (yes, by e-mail), I don't know if I am crying over her or because I can't talk about it with Mami and Tia Chuchi and Tia Dora and Tia Rosa, the first women I loved. Instead, I tell them it is the rigors of graduate school that now make me sob in my mother's arms in the middle of a Tuesday afternoon.

After another night of crying about lost love, I call my mother into my bedroom. Unsure of where to begin, I choose the logical.

"Mami," I begin in Spanish, "it's been a long time since I've had a boyfriend."

She nods and gives me a small smile.

I look at the pink wall of the bedroom I have in my parent's home, the writing awards, the Ani DiFranco CDs, the books." Estoy saliendo con mujeres." I'm dating women.

Her mouth opens, but no sound comes out. She covers her heart with her right hand in a pose similar to the one of the Virgin Mary that hangs over the bed she shares with my father.

Her mouth opens, but no sound comes out. She covers her heart with her right hand in a pose similar to the one of the Virgin Mary that hangs over the bed she shares with my father.

"Mami, are you OK?"

"Ay, Dios mio."

When she doesn't say anything else, I fill the silence between us with a concise history of the LGBT, feminist, and civil right movements, which combined have opened the door to higher education, better laws, and supportive communities of what would be otherwise marginalized people. "It's because of how hard you worked to put me through school that I am fortunate enough to be so happy and make such good decisions for myself."

By this time, my mother is hyperventilating and fanning herself with her other hand. She stammers, "I've never heard of this. This doesn't happen in Colombia."

"You haven't been in Colombia in twenty-seven years."

"But I never saw anything like this there."

In the days that follow, Tia Chuchi accuses me of trying to kill my mother.

We're on the phone. She's at Tia Dora's apartment. As if it's not enough that I am murdering my mother, Tia Chuchi adds with grim self-satisfaction: "It's not going to work, sabes? You need a man for the equipment."

For this, I am ready. I am not being sassy. I really do believe she doesn't know and that I can inform her. "Tia, you can buy the equipment."

She breaks out into a Hail Mary and hangs up the phone.

My mother develops a minor depression and a vague but persistent headache. She is not well, the tias snap at me.

"Don't say anything to her!" barks Tia Dora over the phone. "The way this woman has suffered I will never know."

But she wants me to know.

Tia Dora stops talking to me. She throws away a gift from me because she can see that the present (a book on indigenous religions in Mexico) is my way of trying to convert her to loving women. Tia Chuchi begins walking into the other room when I arrive home. Tia Rosa alludes to the vicious rumors the other two aunties have started about me. "It's terrible," she says, and then: "Sientate, sientate. I made you bunuelos just the way you like. Are you hungry?"

Tia Rosa still complains about the back pains from the accident of years before, but she is living in her own apartment again. In her sixties now, she is a short, robust woman with thick eyeglasses and hair the color of black ash. Her husband is long gone, and since the bed is half empty, Tia Rosa has covered the mattress with prayer cards. Every night, she lies down on that blanket made of white faces, gold crosses, and pink-rose lips.

That my romantic choices could upset my mother and tias had been a given since high school. A lot can be said about a woman who dates the wrong man. But dating the same sex or dating both sexes has no explanation.

My mother now is hurt. More than anything, she is bruised, and she wonders what she did wrong. "This isn't what we expected," she says quietly one day as we walk toward Bergenline Avenue to catch the bus.

I keep thinking that if only I could tell my mother how it works with women, she would understand. The problem is I don't know.

The closest I have to an explanation is a Frida Kahlo painting titled The Two Fridas, where the artist is sitting next to her twin who holds her heart, an artery, and a pair of scissors. That is how I feel about loving women. They can dig into you and hold the insides of you, all bloodied and smelly, in their hands. They know you like that. But this is nothing I can say to my mother.

I miss the conversations now. More than anything, I long for the days when I came home to report that Julio had given me flowers or promised to take me to Wildwood. We have, my family and me, including my father (who demanded to know if Julio was gay the whole time), settled into a region called "don't ask, don't tell." And it is hard, I imagine, for people who have not experienced this to understand the weight of that silence and how the absence of language can feel like a death.

Often when my mother tells me about those early days in her relationship with my father, she mentions the postres.

"He would bring pastries from the bakery," she recalls, smiling and then adding with a warning, "That's how they get you."

Kristina does it with dulce de leche.

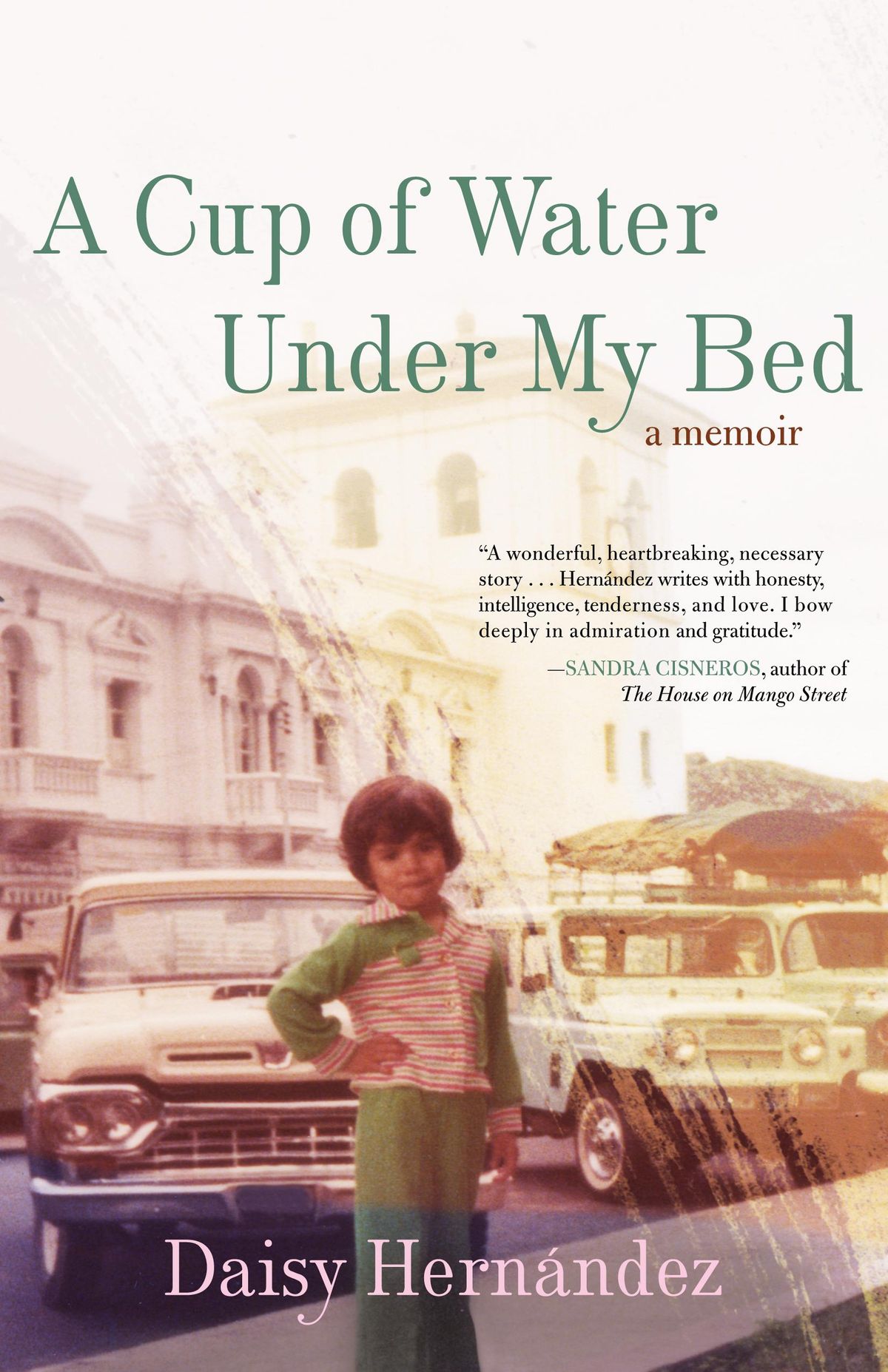

Excerpted from A Cup of Water Under My Bed: A Memoir by Daisy Hernandez, (Beacon Press, 2014). Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.

Her mouth opens, but no sound comes out. She covers her heart with her right hand in a pose similar to the one of the Virgin Mary that hangs over the bed she shares with my father.

Her mouth opens, but no sound comes out. She covers her heart with her right hand in a pose similar to the one of the Virgin Mary that hangs over the bed she shares with my father.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered