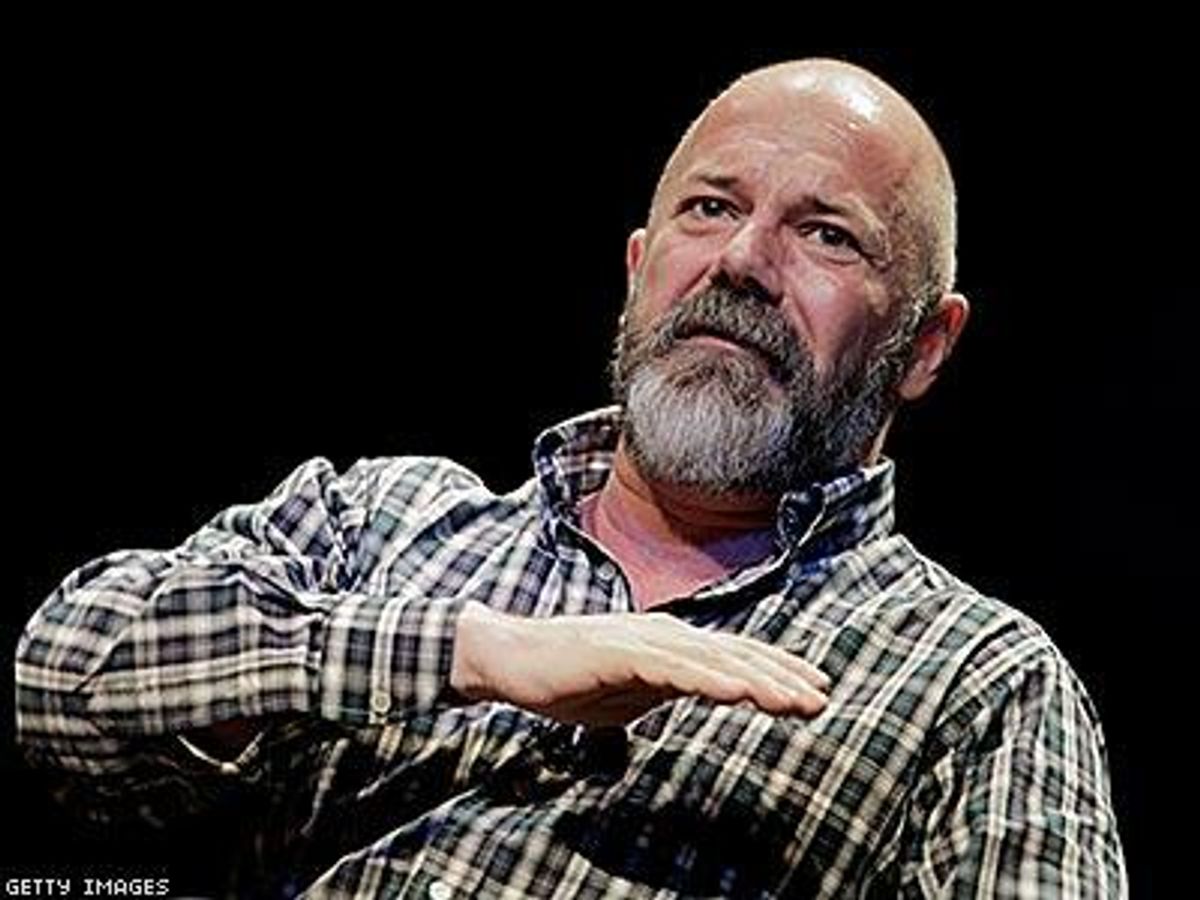

Andrew Sullivan was a junior editor at The New Republic in 1989 when one day the conversation at a story meeting turned to the new phenomenon of homosexuals getting "domestic partnerships." Andrew, a young conservative gay man, piped up.

"Why can't gays get married?" he asked. He pointed at reporter Fred Barnes. "Shouldn't you be for it, Fred? You're an evangelical Christian, shouldn't we all settle down and get married?" Everyone laughed.

"That's a great piece," said editor Michael Kinsley. "You should write that piece. 'The Conservative Case for Gay Marriage.'"

Andrew was twenty-five, an immigrant, Roman Catholic, and barely out of the closet. He had known he was gay since he was seven or eight years old, but it wasn't the sort of thing one announced growing up in the quiet English town of East Grinstead.

"My realization that I was gay was simultaneous with my realization that I couldn't have a relationship like my parents in a way that my brother or my sister could have," he told me when I reached him by phone in Provincetown. He was relaxing at a bar near his summer home, a little tipsy, waiting for his husband to arrive. Through the phone I could hear tourists shouting happily in the background.

"I had no idea what I was going to do when I grew up," he went on. "I knew I couldn't be married to a woman. I couldn't handle that. I had no other understanding of what my future would be." He paused. "I wanted to be a member of the Osmonds at one point. They didn't seem to have wives," (they actually did, but the wives tended to keep a low profile outside of campy holiday specials) "and they were kind of hot. And I could just hang out with them for the rest of my life. I loved the whole idea of the boy band. It seemed like an acceptable way to be an adult without being in a marriage."

During his early twenties, his sister got married. There at the wedding, a relative teased him, "Well, you're next, Andrew!" But his grandmother interjected, "He's not the marrying kind."

Everyone knew what that meant. Growing up Roman Catholic, Andrew was keenly aware of being an outsider when it came to the institution of marriage. "I don't think I ever believed that I always had this right," he said. "As I began to want a normal life in my 20s, I wanted to have a relationship with another man, wanted to have sex and fall in love with another man. But there was no institution, no way we were given an end point. Just dating and fucking forever ... we had no social institutions at all."

Maybe that's why the idea of "domestic partnerships" gnawed at him. The entire arrangement sounded "horrible," he recalled. "Not what marriage was supposed to convey." A relationship should have a recognizable marker, something familiar that wouldn't leave people scratching their heads at a euphemism.

Domestic partnerships, which offered a few token rights and responsibilities and absolutely zero weight of tradition, weren't going to cut it.

His editor badgered Sullivan to write the piece, probably because as a liberal commentator Kinsley relished the opportunity to confound conservatives with their own arguments about the civilizing effect of matrimony. Finally, Sullivan relented, and his piece ran as The New Republic cover story on August 28, 1989. The headline was "Here Comes the Groom," and a picture of two male wedding cake-toppers graced the cover, decades before the image was cliche.

In the piece, Sullivan expressed flat-out annoyance at the very concept of DPs. Under this arrangement, he wrote, anyone simply living together could quality for "a vast array of entitlements" simply by filling out a form. "An elderly woman and her live-in nurse could qualify. ... close college students ... seminarians ... frat buddies."

Marriage had been distilled down to a postal address and a few tax benefits. How romantic. How healthy and stabilizing. A domestic partnership carried little more weight than a dog license.

More importantly, Sullivan argued, marriage would let gays solidify their relationships by fostering "commitment ... social cohesion, emotional security, and prudence." Gay marriage meant stronger, longer relationships and fewer casual hookups. As an epidemic wiped out entire queer populations, he called gay marriage a "public health measure."

"Certainly since AIDS," he wrote, "to be gay and to be responsible has become a necessity." An act of personal commitment wasn't the same as a cure, but it was better than nothing.

"Almost all of it came out of the AIDS crisis," he told me. "It came out of the ashes. I think you cannot overestimate the impact of seeing someone you love have his house yanked away from him as he's dying. You don't forget that, and the commitment to never let gay couples be treated that way again. Ever. And the only way to do that was marriage."

The article struck conservative weasel Gary Bauer as an uproarious joke, and he laughed at it during a subsequent appearance on Crossfire. "This is the craziest idea to come down the pike in as long as I can remember," Bauer chuckled at the very idea, Andrew remembered.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the ideological spectrum, radical queers weren't laughing -- they were fuming.

ACT UP, Larry Kramer's provocative AIDS advocacy organization, called Sullivan "a collaborator" for suggesting that queers take part in what they considered the oppressive forces of integration. A group called The Lesbian Avengers waved picket signs with Andrew's face in crosshairs. A gay ex-marine spotted him buying a drink, berated him for being an assimilator, and eventually chased him from the bar. Village Voice writer Richard Goldstein called him "Rush Limbaugh with monster pecs," a crazily complementary insult.

ACT UP, Larry Kramer's provocative AIDS advocacy organization, called Sullivan "a collaborator" for suggesting that queers take part in what they considered the oppressive forces of integration. A group called The Lesbian Avengers waved picket signs with Andrew's face in crosshairs. A gay ex-marine spotted him buying a drink, berated him for being an assimilator, and eventually chased him from the bar. Village Voice writer Richard Goldstein called him "Rush Limbaugh with monster pecs," a crazily complementary insult.

Sullivan had put forth marriage equality as a means to protect the gay community. But in response, the radical left -- who at that time were the only ones who could have supported so outrageous a proposal -- turned on him. Marriage was simply too conservative, too traditional, too heterosexual for them. He had predicted that attitude, though he couldn't have foreseen just how intense and violent the reaction to his article would be.

"Much of the gay leadership clings to notions of gay life as essentially outside, antibourgeois, radical," he wrote in the piece. "Marriage, for them, is co-optation into straight society."

"There was tremendous debate about whether to pursue the freedom to marry," Evan Wolfson recalled.

Today, Evan is recognized as one of the chief architects of marriage equality, but in the early 1980s he was just a young Harvard Law student, recently returned from a two-year Peace Corps mission to Togo and struggling to find an advisor for his explosive thesis, "SAMESEX MARRIAGE AND MORALITY: The Human Rights Vision of the Constitution."

None of his instructors was willing to be associated with the controversial paper. But he refused to give up, thanks to Yale professor John Eastburn Boswell, and also to the men he met in Togo.

In 1980, Boswell wrote Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, in which he argued that for centuries the Roman Catholic Church either didn't care about queers or actually approved of gay unions. Wolfson devoured the book, fascinated by the idea that at some point the institution of marriage had been changed to exclude gays -- and that it might one day be changed back.

Togo provided a more hands-on perspective. In Western Africa, he met men who were sexually active with men but didn't consider themselves gay. That's largely because the concept of "gay" simply didn't exist; as suppressed as American queer culture was in the late 1970s, in Togo, men simply had occasional sex with other guys, and then they married women and raised a family. When he returned to the United States, Evan was determined not to follow that path.

Professor David Westfall, a relatively apolitical family law professor, eventually agreed to oversee Evan's thesis, and finally, in 1983, it was published.

But just as with Sullivan, Evan encountered resistance from unexpected quarters. Some queers agreed that marriage was a good idea, but so unattainable that even asking for it out loud could set the movement back. "The freedom to marry was going to be too big of a lift at that point," Evan was told. His colleagues urged him to back off -- it was, they said, "too soon ... you needed to lay a groundwork first, and that it would risk jeopardizing the gains we were making."

And then there were those who dismissed marriage as "a patriarchal institution," Evan recalled. "It's damaging to women. It's historically deeply problematic. It's not something we should want." Besides, they said, "we shouldn't be seeking to assimilate, we shouldn't be seeking something that's too much what heterosexuals have. We should be fighting for a different liberation, an alternative meaning to life; that is what gay is all about."

These arguments were infuriating to Andrew Sullivan, who drew a distinction between assimilation and integration. Gay people could still be as radical and weird as they wanted while also participating in conservative institutions, he believed.

But in speaking out for marriage, Sullivan effectively alienated his conservative friends and his gay friends. And the punch line was that he himself didn't even intend to get married. He was perpetually single, had grown accustomed to being "not the marrying kind," and believed he'd never settle down.

"It's too late for me," he told an audience at one of his speeches. "I'm too fucked up to get married." (Evan Wolfson had a similar status for most of his adult life. "Whinily single" is how he described himself at one point to The New York Times.)

Of course, this was years before Sullivan met Aaron Tone, the man he'd marry in 2007 in a small beachfront ceremony, walking down the aisle to the song "Like a Virgin." Talking to me from Provincetown years later, Andrew reflected back at how radically the gay community had transformed in the time between his article and his wedding. He gazed out of the bar at kids running down the sidewalk and gay couples pushing strollers.

"Twenty years ago, it was all shirtless muscle men," he said. Now it was families. Twenty-five years after he wrote the words "to be gay and to be responsible has become a necessity," he could see it happening before his eyes. I was nine when Sullivan's article came out, and I wasn't reading The New Republic. (If the piece had appeared in Cricket, on the other hand, I might have devoured it.) In the 1980s, I didn't even know what "gay" was, beyond a vague awareness that it was a matter of some concern that I identified more closely with Nancy Drew than with the Hardy Boys.

But if I'd been born a decade earlier, I'd have had a very different experience. I could easily have died in my twenties, rather than enjoying the privilege of navel-gazing about weddings in my thirties.

"At the time, it seemed like it was the fucking end of the world," Sullivan said, while bar patrons hollered happily in the background at a soccer game. "I mean, I can't tell you how scary it was. Everybody knew they could die, and there didn't seem to be any cure. Part of that gave me the courage to go out and make that argument. Because I thought it was going to be the last argument I would ever make."

Fortunately, many more years of arguing lay ahead for him. We had to end the call at that point, because his husband had arrived.

"AIDS really broke the silence about who gay people are," Evan Wolfson recalled. Suddenly, homosexuals weren't just gross perverts lurking in the bushes of Central Park. They were family members, suffering mightily, struggling to take care of each other and dying young. "It forced gay people to see our vulnerability in being denied the protections and the dignity and the acknowledgement that come with marriage." Evan said. "It really forced gay people to understand that it was not enough to have a movement that was about being left alone. 'Don't harass us, don't criminalize us.' But now our movement had to be about 'we want to be let in.'"

The AIDS crisis weaponized marriage. What was once a hilarious joke about marrying a horse was now a matter of life and death, a quiver in an arsenal. But whose arsenal was it? Marriage, as Sullivan saw it, could shield us from the epidemic by fostering more responsible sex. It was a cultural inoculation in the absence of a real vaccine.

"Marriage acts both as an incentive for virtuous behavior -- and as a social blessing for the effort," he wrote.

But to radical queers marriage was itself a virus, a tool of the oppressor that, if adopted by homosexuals, would degrade our very identity from the inside out. And to conservatives, gay marriage was an assault on decency. Conservative columnist Mona Charen complained in an article that homosexuals attracted "bisexuals, transvestites, spankers, foot fetishists and sadomasochists," and dismissed gay and lesbian couples as "the sexual underworld."

To these people, marriage was something to be withheld from gays as punishment for their perversion. If AIDS was "nature's retribution for violating the laws of nature," as Pat Buchanan said in 1992, surely heterosexuals were entitled to exact some retribution as well.

Virus or vaccine, punishment or reward; marriage had become a crossroads of ideologies, a metaphorical battleground with a literal body count. And the opponents of equality, chortling to themselves on Crossfire, understood it least.

Excerpt from Defining Marriage, which is now available on Amazon. In addition, the audiobook version is available as a free podcast, with one chapter released every week along with additional bonus material such as interviews, conversations, and stories not included in the book. The podcast can be downloaded via iTunes, Stitcher, and other major podcast services. Both versions are available at DefiningMarriage.com.

Excerpt from Defining Marriage, which is now available on Amazon. In addition, the audiobook version is available as a free podcast, with one chapter released every week along with additional bonus material such as interviews, conversations, and stories not included in the book. The podcast can be downloaded via iTunes, Stitcher, and other major podcast services. Both versions are available at DefiningMarriage.com.

ACT UP, Larry Kramer's provocative AIDS advocacy organization, called Sullivan "a collaborator" for suggesting that queers take part in what they considered the oppressive forces of integration. A group called The Lesbian Avengers waved picket signs with Andrew's face in crosshairs. A gay ex-marine spotted him buying a drink, berated him for being an assimilator, and eventually chased him from the bar. Village Voice writer Richard Goldstein called him "Rush Limbaugh with monster pecs," a crazily complementary insult.

ACT UP, Larry Kramer's provocative AIDS advocacy organization, called Sullivan "a collaborator" for suggesting that queers take part in what they considered the oppressive forces of integration. A group called The Lesbian Avengers waved picket signs with Andrew's face in crosshairs. A gay ex-marine spotted him buying a drink, berated him for being an assimilator, and eventually chased him from the bar. Village Voice writer Richard Goldstein called him "Rush Limbaugh with monster pecs," a crazily complementary insult. Excerpt from Defining Marriage, which is now available on Amazon. In addition, the audiobook version is available as a free podcast, with one chapter released every week along with additional bonus material such as interviews, conversations, and stories not included in the book. The podcast can be downloaded via iTunes, Stitcher, and other major podcast services. Both versions are available at

Excerpt from Defining Marriage, which is now available on Amazon. In addition, the audiobook version is available as a free podcast, with one chapter released every week along with additional bonus material such as interviews, conversations, and stories not included in the book. The podcast can be downloaded via iTunes, Stitcher, and other major podcast services. Both versions are available at