Dance theater's "gentle giant" and Guggenheim fellowship recipient Joe Goode talks to Advocate.com about his career and current works.

March 26 2009 12:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Dance theater's "gentle giant" and Guggenheim fellowship recipient Joe Goode talks to Advocate.com about his career and current works.

San Francisco-based choreographer, writer, and director Joe Goode has been described as "the gentle giant of dance theater." Although his themes are consistent -- community, connection, the artist's search -- his works defy easy categorization. Dancers are as likely to speak as to leap. They might share the stage with video or voice-distorting technology, or expect an audience to find them behind walls or through open windows at a gallery installation. In a 1999 essay Goode praised the "crazy impulses" of art, even if he risked being branded as "the dancer with the chainsaw" or the Peggy Lee impersonator with the fire baton: "For me, art-making isn't a profession or even a calling. It's a necessity, like eating. Without it, I become malnourished and the world gets fuzzy, my grasp on it weak. So, clearly, the craziness of an artist's life is an easy choice when the alternative is starvation."

Goode teaches half the year at University of California, Berkeley, in the department of theater, dance, and performance studies, where he cherishes a diverse group of students from disciplines, like the hard sciences, that don't traditionally combine with performing arts. He founded the Joe Goode Performance Group in 1986. In 2007 he was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship, and in 2008 was named a United States Artists Fellow, one of only five national dance artists to be honored.

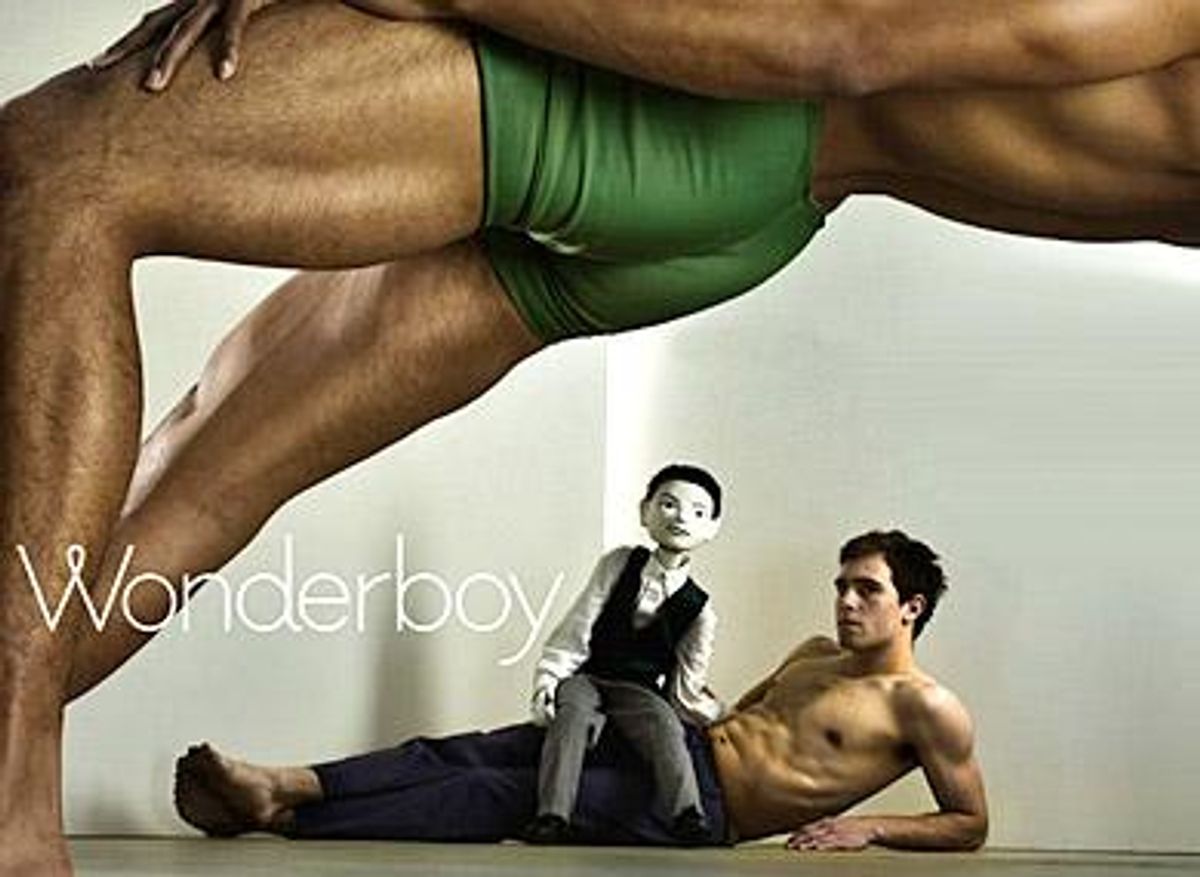

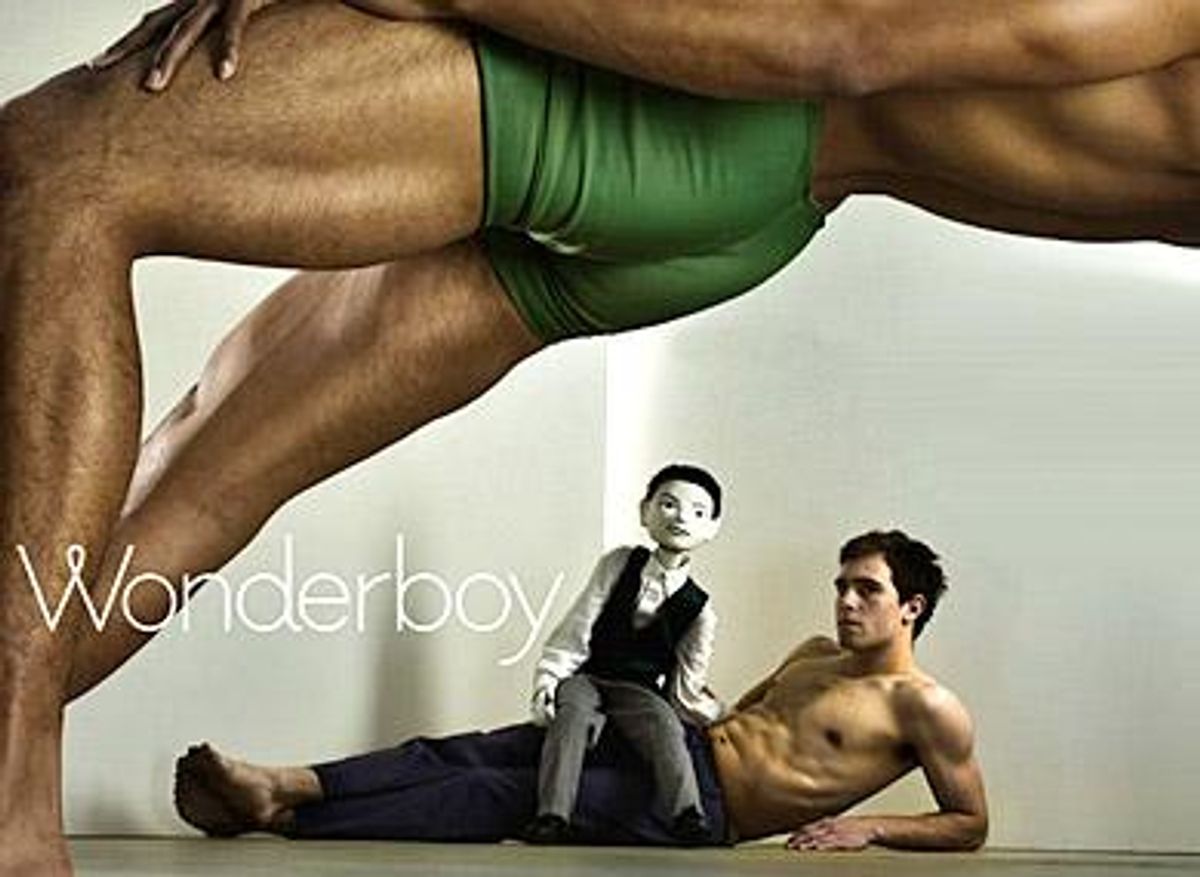

Current works on tour are Wonderboy (2008), a collaboration with puppeteer Basil Twist, and an excerpt from 1996's Maverick Strain .

Advocate.com: Your work has been described as "storytelling theater." When did you begin to feel an urge toward narrative, or maybe a sense of the constraints of modern dance as others were practicing it?Joe Goode: The rule of the dancer as a mute didn't make sense to me. Part of the expression of being human is vocalizing. I feel bereft if language isn't around me, just as I'd feel bereft if I didn't have a full range of movement, if I had to move only naturalistically. So I shuffled around between dance styles and wanting to change the world, and finally decided I had to make my own work.

And did you define that to yourself before you began? It had to be personal. It had to be a statement, deeply drenched in what I felt about life, about the world. And being a gay man, and dancing as a gay man in the 1970s in New York among gay choreographers whose gayness was nowhere in their work -- that affected me. Why wouldn't I want to illuminate the strong women and vulnerable men in my life? I don't want to always stand behind the woman and open her legs and show her as some vulnerable flower, something compliant. I want to be the flower. So in our company, we lift each other and move each other. I like that parity between genders.

So your sexuality became a large part of your choreography. Always there's a homosexual thread in my work. Growing up in suburban Virginia, I didn't have that. I felt so outside life, so different, so broken, so in need of repairs. It took years to realize that I'm OK. I bring that to the center of my work. In the late '80s I made a piece called 29 Effeminate Gestures -- what it meant for a man to own them, have them, and live in them: how scary for the world and how unsafe for the carrier of them.

That makes me think of some of the discussion surrounding Prop. 8 -- this comes up perennially in the gay rights movement -- about how gays and lesbians should behave in public, how we should represent ourselves to the straight world. Some argue that we shouldn't be flying our freak flag, that progress depends on people recognizing our common humanity. I like to think it's our common complexity that's our point of overlap. We're all equally complex and capable of embodying our queer selves, our fallible selves. Trying to scrub ourselves off and make ourselves perfect isn't going to work. Straights aren't perfect either. We're imperfect. We're all in a state of decay. We can acknowledge each other in a friendly way. In accepting our difference, they're accepting their own. You can be complex and full and accept your own self.

Is there an autobiographical element to Wonderboy ? Yes, and that's true for my collaborator, Basil Twist, as well. Wonderboy is an ultrasensitive puppet who discovers he's an artist and has some aesthetic power, that his way of seeing things can teach people. I went from being an introverted and nearly suicidal teenager to discovering art. And it's still a survival technique for me, as it is for Wonderboy, a way to make sense of the world.

Three dancers have to operate Wonderboy at all times. But instead of being in black and veiled, as they'd be in bunraku [the classical Japanese puppet art], they're exposed. They're responsible for their gestures and his at the same time. And these are contorted positions. Dancers just want to flow and be open, but when you're holding a puppet, there's a constraint and tightness involved. Basil encouraged the dancers not to be perfect puppeteers but to think of Wonderboy as a real character, thinking and reacting in each moment, and they began to say things to me like, "Wonderboy doesn't like it over there." Now we treat him like a seventh member of the company.

We talk a lot about disappearing into the material, and Wonderboy pushes that. He's the star of the show and the audience is really focused on him.

How do you make a decision about pairing older work with newer? The excerpts from 1996's Maverick Strain with Wonderboy, for example. It's contrast, mainly. With Wonderboy, I was working with the image of a silent French film -- thin, reedy, off in the distance. This felt like the right mood for Wonderboy. He's all about his sensitivity and his longing -- his homoerotic longing, wanting to be with the boys. So it was about this state of longing and this state of wonder too, while Maverick Strain [a deconstruction of Arthur Miller's screenplay for The Misfits (1961)] is about ruggedness, this disease of ruggedness, particularly as a man in America. It's a very lonely, principled, dogmatic life. And even though the culture is more subtle about it now, we're still giving those messages to little boys with the toys we give them and how we treat them.

Maverick Strain is a big, ballsy, overt piece in a way that Wonderboy is not. Wonderboy is a fragile, porcelain thing. So I thought it was a good contrast. They're both about how a man is expected to live in the world.

Will you be premiering a new piece this fall in San Francisco? Yes, it's called Traveling Light. I'm delving a little into my Buddhist studies and the desire to live a less-encumbered life, to move into the future less attached to worldly possessions and vitality. This is about accepting aging too, and about ecological change, about ending our fossil fuel dependency and turning to alternative sources of fuel. I'll be collaborating with my longtime lighting designer, Jack Carpenter. It's going to be staged in a warehouse, and much of the work will happen under a large industrial light that travels across the warehouse, and the audience will have to move too.

Wonderboyhas had a fantastic press response. When you read that one of your "characteristic moves" is an upside-down split-leg lift, does it make you self-conscious as a choreographer? Do you think of it every time you're about to choreograph a lift? I'll tell you the truth. I don't read reviews for that very reason. I'm a flower. I'm very sensitive to criticism. And it can even be a positive review, but the passage where they say the piece is slow, that's what I'll attach myself to. So I don't read them. They come and they go. I don't want to know. I'm living in my little bubble.

I do want to have conversations about the work and its growth, but that's a very privileged position. I talk with very few people about it, and their critical feedback is huge. And you reach out to collaborators who are going to push you out of your comfort zone. Before I met Basil Twist I was a puppet-phobe. I had a real attitude. But when I saw what he could do with puppets, I wanted to work with him.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered