Last spring Mark Duplass wrote a one-line e-mail to Josh Leonard that would eventually launch their shambling careers in gay porn all the way to a four-minute standing ovation at this year's Cannes film festival. As actor-directors, they met on the independent film circuit. Duplass's Baghead had been a hit at Sundance, and The Blair Witch Project , one of Leonard's first acting gigs, was the most successful film ever to debut in Park City.

"I sent Josh one line: 'Do you want to play best friends in a movie this summer?'aEUR%0" Duplass explains over drinks at an outdoor cafe in Los Angeles's Silver Lake neighborhood. "And Josh wrote back, 'Hell, yes! What's it about?' And I said, 'Look, don't worry about that, it's going to be great.'aEUR%0"

Leonard, now sitting beside him, deadpans, "Don't ever let me agree to be in a movie again before I know what it's about."

Humpday is the story of two straight longtime friends who decide to have sex with each other and film it. It starts as a joke that becomes a challenge that then evolves in surprising and sweet ways into a genuine exploration of male friendship and the shape of desire. Ben (Duplass) is newly married and settling into domestic stasis when Andrew (Leonard) shows up from Mexico with ugly gifts and a beard to give him gravitas. On his first night back Andrew meets and introduces Ben to a polyamorous lesbian couple and their friends, who tell them about the Hump! festival, an actual and ongoing amateur porn showcase in Seattle produced by the alt-weekly The Stranger . "What kind of porn would you two make?" goads one of the women, played by Humpday director Lynn Shelton. "Two straight dudes having sex," Ben says. "It's beyond gay."

"You'll get the shit boned out of you," Andrew proclaims.

"No, you'll get the shit boned out of you ," Ben fires back.

Suddenly, it's on. Starting with a drunken, improbable double dare, Humpday follows these two friends over the course of a single weekend, from wicked hangovers the morning after to Ben's searing conversation with his wife to get permission for the "art project," ending up at the shoot in a hotel room. "We knew the concept was so absurd that the movie couldn't work on just the level of gimmicky hetero male one-upmanship," Duplass says. "There had to be a reason on an emotional level so that on a pillow at night, each of these guys had each picked this project to be a symbol of something missing in their lives."

In the film's trickiest and most refreshing angle, the obstacle to overcome is not the closet door.

"You're pretty solidly not gay," Andrew asserts to Ben in the film, and Ben answers, "Yeah, and I think the same about you," and we believe them. Apparently, the closest either has come to gay sex is an anecdote Ben tells about a video-store clerk with incredible eyes who coerced him into watching boring documentaries -- a "quasi-autobiographical" tale, says Duplass, that had him wondering what sex with a man would be like.

"Did you think about his balls?" Leonard asks at the time.

"No, I didn't," Duplass answers. "I just liked the way he looked at me."

"In hindsight, did you think about his balls when we were filming?"

"I am thinking about them right now," Duplass says, drifting off. "He'd be so much olderaEUR|"

Humpday isn't a coming-out story, Brokeback captured on camcorder, or an advertisement for bisexuality. If anything, it takes the latent energy in the homo-anxious bromances -- I Love You, Man or Jimmy Kimmel's "I'm F**cking Ben Affleck" -- and surfaces with something far more searching, awkward, and honest. Cannily, Ben's and Andrew's motives have more to do with self-esteem than sexuality -- the increasingly tenuous connection between who they are and who they think they are. Tucked-in and buttoned-down, Ben is desperate to prove "he's still a wild man inside," says director Shelton, and itinerant Andrew, "the guy who will try anything once," needs proof that he can actually finish something. When Ben's wife finally confronts him about his motives, the movie has the bravery to understate his case and not let him entirely understand his urge to have sex with his friend. "I just know it's important to me," he tells her, and she allows him to proceed, saying, "I don't want to live with you with this buried in you."

It's a mistake to think of Humpday 's story as plot, since the film was more like "carefully supervised jazz," Shelton says. Every scene was improvised by the actors, all situational riffs building to the big open question that no one had the answer to: What would happen in the hotel room at the end when they went to shoot the video? "I had every component of the script -- I knew the beats and objectives and the emotional development, I just didn't have a script," Shelton says. (No writer is credited with the screenplay.) Like other standouts in mumblecore -- a filmmaking movement known for its focus on personal relationships, improvised scripts, and nonprofessional actors -- a Cassavetes-style looseness gives Humpday a stumbly, verite warmth. As outrageous as the film's conceit might be, one never feels the actors reaching for their marks, because Shelton let Duplass and Leonard create them. Before shooting, they retreated for three days in Duplass's mother-in-law's apartment to develop the friendship's backstory, only glancingly referred to in the film.

Using an outline for a guide, they shot the film in sequence (another small but essential innovation of Shelton's method). Every scene then psychologically led into the next without contrivance. Hours of improvised takes were distilled and "redeemed" in the editing room, Shelton says. As a group, they decided to keep the film's climax a mystery even from themselves. "That was Mark's idea," Shelton says. "He didn't want anybody playing toward an inevitable end."

Shelton is a former documentary filmmaker, whose short films, about miscarriage and women's relationship to their body hair, were "personal and chicky," she says. After shooting her first dramatic feature -- We Go Way Back , about a 23-year-old girl who reads a letter written to her by her 13-year-old self -- Shelton found herself frustrated by the boggy, top-heavy methods of traditional filmmaking. "Actors would blow me away in audition, and then I'd get them on set, around 40 crew and lights, and they'd freeze up. Getting a natural performance was like pulling teeth." For her next film, My Effortless Brilliance , she slashed the size of the crew, reduced the lighting rig, and employed a small camera to create an easy set, focused on the needs of the actor. "Then I thought, Instead of casting people to fit this person I had in my head, what if I found people in real life that I knew or wanted to work with and cast them? "

An effusive former actress, Shelton is a married mother who describes herself as "pretty straight," with a particular interest in the private dynamics between men. My Effortless Brilliance , which was Shelton's first improvised experiment, tracked the reunion of a famous young novelist and his former best friend in a wooded cabin, where there were no women for miles. "I felt such privilege watching these guys alone," she says. "Like I was privy to this secret world." The alt-buddy romance of Humpday might seem like unlikely subject matter for a married woman, but Shelton is the ideal voyeur: curious, nonthreatening, and without agenda. How likely is it that a gay or straight male director could have pulled off the same? "The subculture always knows more about the dominant culture than the dominant culture knows about the subculture," Shelton says. (This may help to explain, for example, how Taiwanese director Ang Lee could direct Brokeback Mountain so well -- and how Annie Proulx could write it.)

From the audience's perspective, one can feel Duplass and Leonard performing for Shelton, taking risks and triangulating their lust through the camera and, by extension, her, their provocateur. (Both actors are straight, so it's understandable.) This dynamic may be at the heart of Humpday 's sensitivity. Bromances made by straight men -- like I Love You, Man ; and even Andy Samberg and Justin Timberlake's SNL parody sketches -- can only point at male intimacy, an affection that draws a sharp line at the bedroom. Gay culture has made it prevalent if not permissible terrain to think about that boundary, where it stops, and why. Shelton, by her presence, is the permission to cross it. During the climactic scene -- the longest shoot of the film at 12 hours straight -- Shelton was one of the camera operators. "I was shaking the whole time," she says. "It was just the two of them being their characters, one long, brilliant improv." (Shelton has asked us not to reveal the ending, and why spoil it?)

It'd be an overstatement to say the humanist Humpday makes a case about orientation -- that it's fixed or fluid or that male friendship is only latent foreplay. If anything, the film celebrates enthusiasm, Ben and Andrew's old college try at anal. But it is exploring those boundaries. Unfortunately -- and expectedly -- their notion of sex between men sounds more like rape than anything else, a "fast-food pounding," Duplass says, and it's played for rueful laughs. Quickie sex or, rather, a lunge at each other "seems more palatable to Ben and Andrew than the five-course meal. It's a pretty good representation of dude sexuality with somebody you're not in love with, gay or straight."

"A sticky end," Leonard adds.

It's in the small, charged intimacies, anyway, that Ben and Andrew win over each other (and, one would imagine, audiences): the hug between long-lost friends, the scuffle over the basketball that ends up with the two horizontal, and, of course, the kiss.

Their extended lip lock in the hotel room -- the film's genuine climax -- was "a full-powered leap off a high dive" for Leonard. It was the first time he'd ever kissed a man, and the thrill and danger of that shows. "It was pretty intense," Leonard says. "Mouths were definitely open, though I'm not sure about tongue."

Duplass adds, "I got a pretty good sense of you from that. Essence de Josh ."

But the experience confirmed for Leonard his deep-seated suspicions about himself.

"What I learned after kissing Mark -- " he starts.

"Careful," Duplass interjects, "I'm sitting right here."

"-- was that I don't want to kiss another man. It just didn't trigger anything phermonally inside me," Leonard says. "But Mark's spit does taste wonderful."

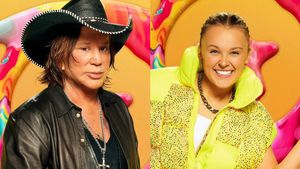

Here's our dream all-queer cast for 'The White Lotus' season 4