When people with opposing viewpoints engage in dialogue, change is possible. It doesn't happen all the time, or always easily, but it happens.

That's what filmmaker Roger Ross Williams is seeing with the dialogue around God Loves Uganda, his powerful new documentary about American fundamentalist Christians' export of homophobia to Africa.

The impact of that meaningful dialogue is likely among the chief reasons Williams' latest documentary was just announced as a serious contender for next year's Oscar for Best Documentary, earning a spot on the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences' "short list" for the 2014 Academy Awards, along with 14 other films, according to the Associated Press. Williams already has an Oscar at home, which he earned in 2010 for his documentary short Music by Prudence. Official nominees for next year's Oscars will be announced January 16, 2014 and the 86th Annual Academy Awards will be take place March 2.

"The most amazing thing happened at this recent screening in Malawi," says Williams, whose film has been shown around the world and is now having a theatrical release in the U.S.

After a group of clergy and laypeople, the latter largely LGBT but closeted, viewed the movie, they engaged in a nationally broadcast debate about homosexuality, with most of the religious leaders condemning it. But then a few of the LGBT people in the audience made coming-out statements, and one of the ministers recanted the antigay comments he had made earlier. "I'm withdrawing my statement," he said. "Gays and lesbians are good."

"That's why I made the film -- moments like that," says Williams. The minister who recanted said he'd never met a gay person, at least one he knew was gay and the film and the dialogue made him realize they were humans like him. "They had built up this monster in their minds," Williams says of the religious leaders.

In making God Loves Uganda, Williams found that many of the fundamentalist Christians spreading their antigay dogma abroad are not monsters either, although their message is a harmful one.

"What really surprised me was how nice and well-mannered the fundamentalist evangelicals were," he says. "I had in my mind, as a gay man, demonized them, the same way they had demonized us. ... They're really nice and you like them, and they're preaching something really dangerous and don't even realize it's dangerous."

Step inside that Malawi screening in the video below:

Williams thinks his film, along with other work being done by LGBT advocates, can help bring people to this realization. God Loves Uganda is the first feature-length documentary directed and produced by Williams, a 2010 Oscar-winner for Best Documentary Short Subject with Music by Prudence, a portrait of Zimbabwean singer-songwriter Prudence Mabhena and her band; she and all the band members have physical disabilities.

To film Music by Prudence, Williams made his first trip to sub-Saharan Africa, and he was struck by the strong influence of fundamentalist Christianity on the region. Africans, he says, are highly spiritual people anyway, and conservative Christian ministers have found a ready audience, especially by preaching a prosperity gospel to a population that's vulnerable to this message.

They've also brought an antigay message, though, which has resulted in such legislation as Uganda's infamous Anti-Homosexuality Bill, some versions of which would prescribe the death penalty in certain cases. The bill has yet to be passed by the nation's parliament, but simply by being proposed, it serves as a tool that can be used to threaten LGBT people, Williams says.

"After reading about the bill, I thought, Uganda's the perfect place to explore the evangelical fundamentalist hold on the continent," he says.

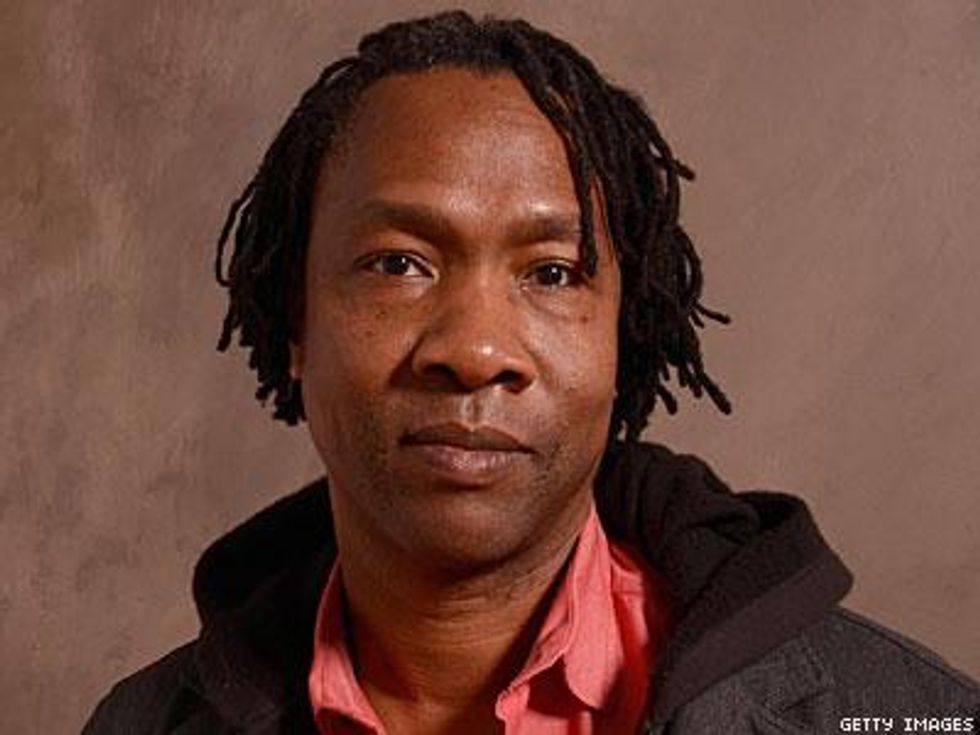

Left: filmmaker Roger Ross Williams

Left: filmmaker Roger Ross Williams

When he went to the nation in 2010 to begin his research, the first person who visited him at his hotel was gay activist David Kato, who would be murdered the next year. Kato said the story Williams had in mind definitely needed to be told. "I needed no further encouragement," Williams says.

His film features several preachers of antigay dogma, both foreign and indigenous, working in Uganda. The foreigners include Lou Engle, founder of the Call ministry and a leader in the Kansas City, Mo.-based International House of Prayer, which has a branch in Uganda; IHOP founder Mike Bickle; and several people who assist in IHOP's Ugandan missionary work, such as Jo Anna Watson, married couple Jesse and Rachael Digges, and Jono Hall. There's also Massachusetts-based Scott Lively, whose work in Uganda helped inspire the Anti-Homosexuality Bill and who is now facing international persecution charges for fostering antigay animus in Uganda. On the indigenous side are Pastor Martin Ssempa, a staunch supporter of the bill, and Pastor Robert Kayanja, who leads a megachurch in Kampala, the capital of Uganda.

It also spotlights religious leaders who have stood against homophobia, and Williams calls them the heroes of the story. Christopher Senyonjo, the former Anglican bishop of Uganda, is "a saint," Williams says. "He's just the most loving man. He believes that God is love, and he preaches love and acceptance for everyone."

After retiring, Senyonjo stared a counseling service, but the church defrocked him and stripped him of his pension because he told clients that being gay was OK. He refused to back down, and finally the Elton John AIDS Foundation came to his rescue with a grant to start St. Paul's Reconciliation and Equality Centre in Kampala, a nonprofit organization that offers a variety of social services and one of the region's few affirming worship spaces for LGBT people. Then there's Rev. Kapya Kaoma, an Anglican priest who once served in his home country of Zambia and now works within the Episcopal diocese of Massachusetts. A research firm sent him to investigate the antigay climate in Uganda in 2009, but he eventually had to flee the country because of threats of violence.

Before the coming of foreign missionaries, the filmmaker says, there was some homophobia in African nations, as there is in most cultures, but there was also some degree of acceptance. The kingdom of Buganda, now a region within Uganda, had a gay king in the 19th century. And Sylvia Tamale, a feminist lawyer, professor, and activist in Uganda, has written extensively on the variety of sexual practices in Africa.

Uganda was particularly fertile ground for fundamentalist Christianity, Williams says, not just because of African spirituality and certain churches' prosperity gospel, but also because President Idi Amin had outlawed this type of Christianity during his dictatorial rule in the 1970s. After he fell from power in 1979, this firebrand of religion became identified as a good thing. And religious scapegoating of LGBT people, Williams adds, takes attention away from government corruption and other problems.

The missionaries working in Uganda now, he says, see the nation as a test case in their effort to establish their strain of Christianity in Africa, a strain that blurs the boundaries between church and state. They have pretty much given up on the U.S. and Europe, he notes. "Every single American evangelical I talked to says they feel that they've lost the culture war in America," he says. So, he adds, they see Africa as "the new center of Christianity."

He emphasizes that the efforts to oppress LGBT Africans are not limited to Uganda. In Nigeria, for instance, Parliament has passed a bill that would criminalize same-sex relationships and even membership in gay rights groups; it awaits the president's signature.

LGBT activists in Africa have done a good job of fighting back, Williams says; the attention that Uganda has received from Western politicians and media has been particularly helpful there. But these activists are fighting a massive, well-funded adversary. "It's a David and Goliath type of situation," he says.

Nonetheless, he sees hope. "It's a long struggle, but it was a long struggle in America," he says.

And the process of making the film, and the response to it, has shown him that dialogue is possible and that it can change hearts and minds. At the end of filming, Williams asked Jo Anna Watson, who had said LGBT people should be imprisoned, if she thought he deserved that. She said no, and told him she loved him, and others at IHOP told him they had become more compassionate toward gays. At a Sundance Film Festival screening for seminarians, some students from conservative schools came out to him. A fundamentalist Christian couple who have a gay child started a support group for parents in similar situations after seeing the film.

"I realized there could be a dialogue," the filmmaker says. He adds that the subject is personal for him; he comes from a family of Baptist ministers, some of whom are involved with the largest black church in his hometown of Easton, Pa., and he has long felt estranged from organized religion. "This movie is my way of confronting my own struggle with faith," he says.

One of his next projects will also deal with faith, in this case a religious leader who has long been a champion of LGBT rights -- he's making a short documentary on Desmond Tutu, the former head of the Anglican Church in South Africa. In addition, Williams is working on a multimedia project called Traveling While Black, about the history of travel discrimination, and it will include a film, a museum exhibit, and more.

In the meantime, he's gratified by the dialogue that has come out of God Loves Uganda. "Everyone I interacted with, they're different," he says, "and so am I."

God Loves Uganda is currently playing at theaters in New York and Los Angeles, and it will open in more cities in the next few weeks, in addition to being screened at churches, colleges, nonprofit groups, and film festivals around the world. To find a screening, visit GodLovesUganda.com. Watch the film's official trailer below.

Left: filmmaker Roger Ross Williams

Left: filmmaker Roger Ross Williams

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered