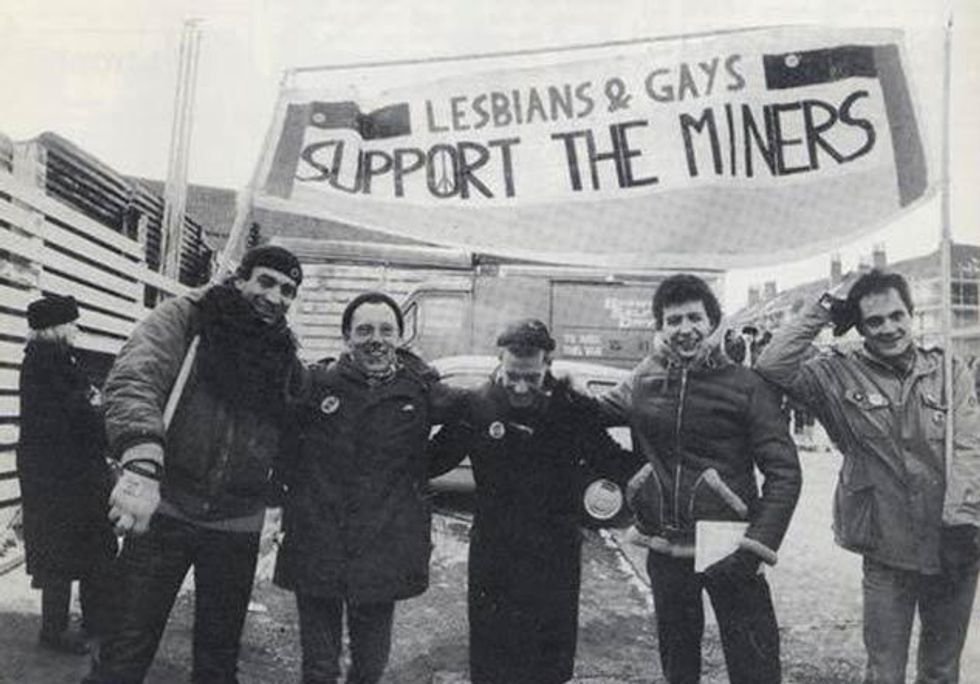

There's a wonderful movie out there: Pride by Matthew Warchus. But more importantly there's an amazing story back in the public spotlight thanks to the film, which recounts the experience of the group Lesbians and Gays Support Miners.

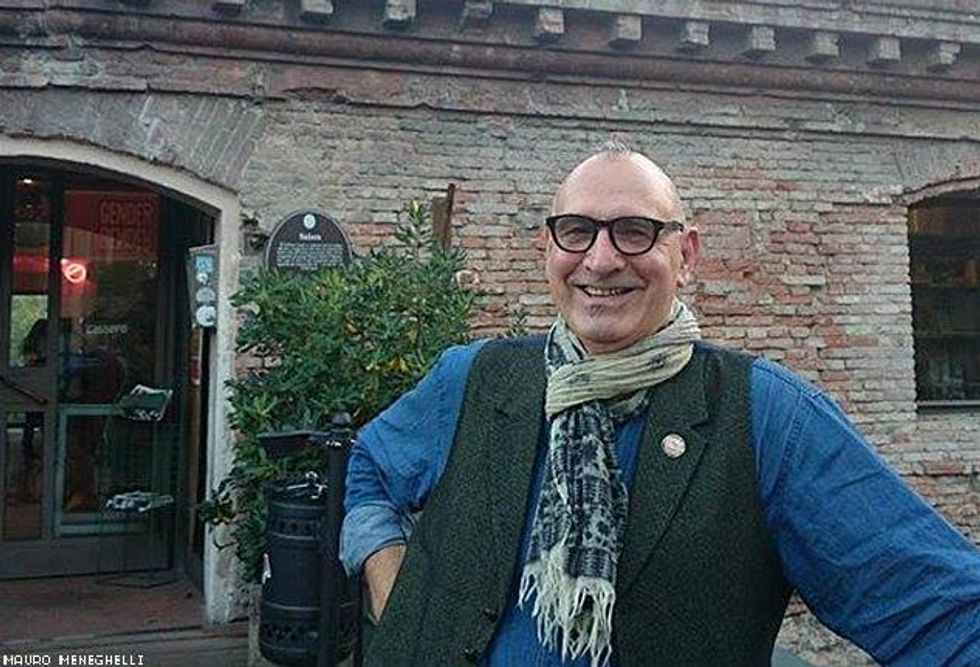

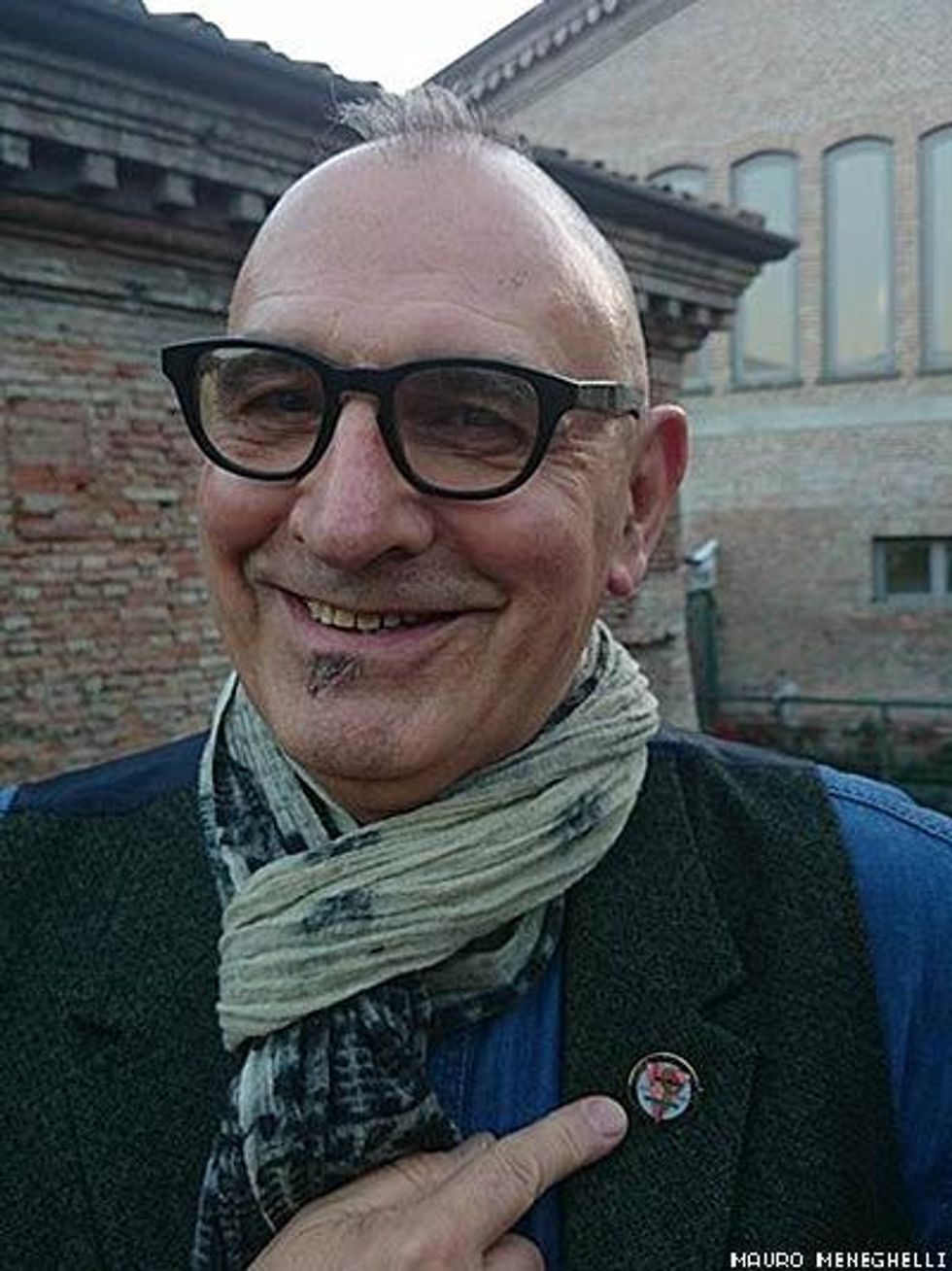

During the Thatcher era, in 1984-85, a London-based group of gays and lesbians supported the miners striking against a government decision to close mines all around the U.K., including in Neath, Dulais, and Swansea Valleys. It has been a successful fight, both for miners and for the U.K. gay movement, which found in the miners its best ally for the years to come. During the Gender Bender Festival in Bologna, Italy, I had the occasion to meet Jonathan Blake, one of the original members of Lesbians and Gays Support Miners, interpreted in the movie by Dominic West, and we spoke about the group, Pride, and LGBT rights.

The Advocate: How did you get involved in Lesbians and Gays Support Miners and what pushed you into it?

Jonathan Blake: First of all, I've always believed in trade unions. I think they're important.

But everything happened after a life-changing moment, because in October 1982 I've been diagnosed with HIV -- it was very early -- and in the December of that year I tried to commit suicide, but I couldn't do it because I couldn't bear the idea of someone having to clean up after me. So, if you can't die, it's better to go on and live. It was very difficult because my self-esteem was gone to nothing.

In that period I saw there was a demonstration with a coach leaving from a well-known gay bookshop in London, Gay's the Word, with a group called Gays for a Nuclear-Free Future. I screwed out my courage and I thought I was going to join them. When I arrived there there was this guy wearing gumboots and amazing pantaloons and he was Nigel Young, my partner since then. He has been a political activist all his life, the next days we started to spend more time together and then he said, "Why don't we find a squat together?" So we did! After a while we had to move again and we moved into this old established lesbian and gay squat in Brixton. Then on Gay Pride 1984, LGSM was formed and it was natural we get involved in it.

For me, one of the most important things is that I needed to keep busy to think less about HIV. We were thinking that in a week or in a month, maybe in a year, I was going to be dead, so I had to think less about it.

And of course that of the miners was such an important issue. We knew what the state did to communities, to our community, and suddenly they had picked on the miners, these people who were always hardworking, and the state was vilifying them. For us it was obvious to support them, because it was a common cause.

Pride focuses mainly on the way miners perceive gays, and that's the funny part, but how did gays perceive miners? Maybe gays had to face their own prejudices on miners.

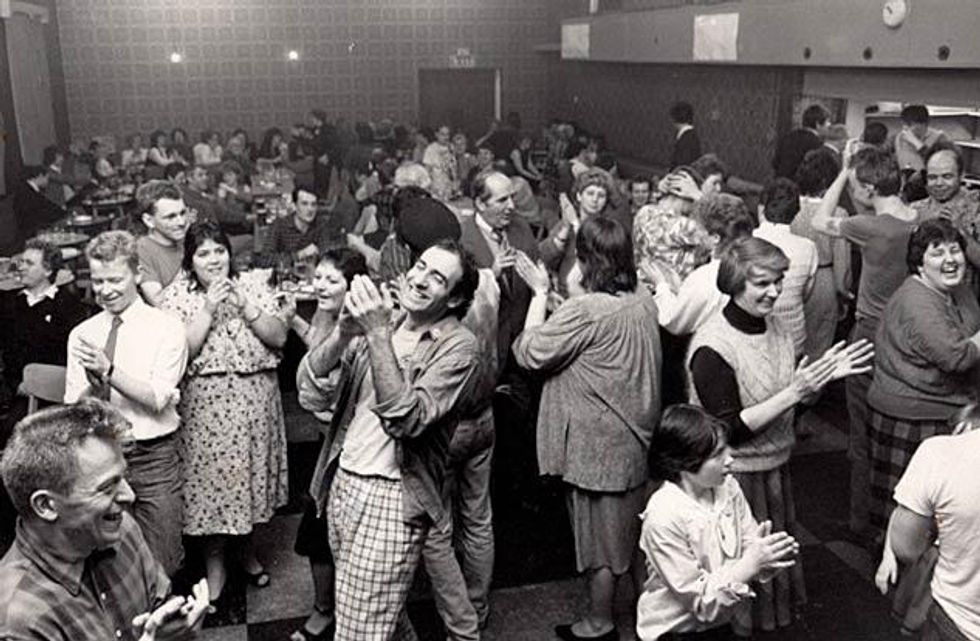

We were very aware that our community and each of us was constantly under attack. So on one hand it was just going there, feeling to be in a just cause with them. Apparently we thought too much on how we were going to be received ... you would do it on your impulse because it was the right thing to do. What was amazing is that we were received with such warmth and such generosity. A lot of ours, or mine, preconceptions on what the miners were, about being burly and bluff and homophobes, were dispelled. But, within that, for instance, the character that Bill Nighy plays, Cliff, was a miner but he was a gentleman and people knew that he was gay, and about that there's such a beautiful scene in the movie. People constantly wonderfully surprise you, there was nothing but warmth and generosity. That's extraordinary when you think of what they were going through, when you have the weight of the state against you, vilifying you, making you outcast, criminal.

What did you have in common with miners?

We understood their situation because we were criminalized too -- there were lots of gays under 21 and they were all illegal. If you had sex with someone under 21 the law could break down your door, and what was interesting is actually that the law in U.K. was about "consenting adult male in private," and "in private" meant that if you shared a flat with another person and you dragged someone back, the police could break down your door and arrest everybody in there because it was no longer in private. So, we've come a fair way since then but there's a hell of a long way to go.

In the next years, when the gay movement needed it, miners were there to help -- they led the London Pride in 1985, for example.

That was extraordinar,y and what was fascinating is that, for myself, I don't think that I was really aware of what a huge and generous gesture that was. We supported them because we believed that was important, because their communities were important, and as Mark says in the film, it is the miner that goes down underground, that digs the coal, that does the dirty work so you can dance to Bananarama!

Who is, or who should be, the best ally of the LGBT movement in the U.K. right now?

We live in such a different time ... Everything is atomized, we all live such individual lives, there aren't communities. What is amazing about this space we are in [Il Cassero, Bologna] is that it is a living and working LGBT center -- there used to be one in London many years ago, but it basically disappeared because of the whole situation of HIV and AIDS, when all the money that was around went into dealing with that. But because we all live this atomized lives for the most part, people don't come together in the same way.

In general there are other causes to support -- for example, the situation of how the Chilean government is treating the families of the Chilean miners that were killed in 2010 mine collapse, but at this point I can't really see one cause that can be "the next cause to support."

Yeah, I think that's true. LGBT communities should be focused on supporting local issues, and then different local communities can challenge together national politics.

To build a community you need to smell and touch and stand just next door to someone on a demonstration; it's fine you can use technology to communicate in the cyberspace, but actually the important thing is to be there to build communities physically.

Have you been or are you currently involved in some other political fights?

I'm very fortunate because me and my partner live in a housing cooperative, and because of that we are always fairly active -- the housing cooperative is fully mutual. We own nothing, but the cooperative actually owns 35 houses, there are 100 people in the co-op, the co-op needs services, and as a member of the co-op I am active.

LGSM came together to support the miners and when the fight was over the group had done what it set out to do and decided to cease. But because of Pride the group LGSM has reconvened as LGSM 2014, and we'd like to raise funds to help, for example, the families of the Chilean miners and to make accessible on the web the LGSM history. We're hoping that with the help of trade unions we can commemorate the 1985 involvement of the South Wales miners into leading Gay Pride, and we'd like to have a large trades union presence plus former miners and LGSM with it's banner leading the next LGBT march in 2015.

MAURO MENEGHELLI is with Gender Bender, an international festival introducing the Italian public to new imagery related to gender identity, sexual orientation, and body representation stemming from contemporary culture. See more about it here.